Tianxia: Blood, Silk & Jade by Wapole Languray

| 1 | Intro |

Intro

Original SA post

Tianxia: Blood Silk and Jade is a Wuxia/Kung Fu supplement and setting expansion for Evil Hat’s Fate Core rule system by Vigilance Press, written and created by Jack Norris, with art by url=http://denisesjones.deviantart.com/]Denise Jones[/url]. Created properly after a successful kickstarter campaign back in 2013, and officially released in 2014, Tianxia is one of the best damn Wuxia games I’ve seen.

See, most games of this sort, like Qin: Warring States, Weapons of the Gods, Wulin, Heroes of Ogre Gate, etc. have an issue I don’t like. They focus way too much crunch on simulating the nitty gritty of kung-fu combat, there really isn’t a lighter game in the genre I’ve ever seen besides Tianxia that isn’t like Wushu, so light the genre is basically just flavor, or just cramming kung-fu into an existing fantasy setting.

Also, the game is pretty as hell, and I’ll be posting as much art as I can for you guys to ogle at.

Now, I love Fate, it’s probably my favorite system ever, and Tianxia is a wonderful combination of setting and really solid mechanics that hit all the right spots. You do require the Fate Core rulebook to play, but it’s Pay What You Want so that’s no excuse.

Anyway, Tianxia is great, I wanna show it off. It’s an obvious labor of love from someone who really really loves wuxia as a genre, so I’ll also be expanding on some of the concepts and setting elements with Real Life History Stuff as we go, because I’m a nerd for it too. So, with that out of the way, let's get started with Chapter 1!

Welcome to Tianxia

The Occurrence at Peach Blossom Bridge posted:

“The right ground can turn a man into an army, and an army into a collection of fools.” Ma Wei Sheng’s father had told him this when he was eight.

His father, the Great General Ma, victor of countless battles fought for his Emperor and the Great Empire of Shénzhōu. He was always right, a fact which comforted and frustrated the young swordsman on alternating occasions. Today, watching thirty swordsmen rush him across the opposite end of the narrow bridge was one of the comforting times.

He had stumbled upon the White Turbans by accident. A murdered farmer, a young child asking for his aid, and a youthful enthusiasm for justice and chivalry had led him to uncover the sect. Their ultimate goal was to overthrow the empire and cast down the priesthoods, replacing both with their heretical theocracy. Wei Sheng had not figured out how the death of the farmer featured in their plot. He might never find out now, not if the next few moments went against them. Of course, he was not unprepared.

“Swift and thoughtful action saves lives. Swift and thoughtless action ends them.” Another of his father’s sayings, and again, so very appropriate. He had fled the Turbans when he saw their numbers. Not out of fear, but only to find the right ground. He found it at Peach Blossom Bridge.

The bridge was narrow and unimpressive. It crossed a small tributary of the Silk River, little more than a stream but just fast and deep enough to make crossing uncertain. The bridge had been built to allow for the small amounts of traffic between the nearby villages, and it was difficult for more than three or four men to walk side by side. In other words, it was perfect.

Ma Wei Sheng watched as the White Turbans ran across the bridge towards him, all drawn swords and murderous fury and fear. They needed him dead, he knew, lest he escape, bringing soldiers and magistrates to crush their sect.

Unfortunately for them, escape was not Wei Sheng’s strategy. He did not wish to avoid fighting. He simply wished to find the right place for it—a narrow bridge where their thirty fanatical fighters became rows of three or four pressing against each other with little room to swing their blades. On this little, unassuming bridge, Ma Wei Sheng was the army, and they merely a collection of fools.

The White Turbans slowed momentarily when they realized he had stopped. Perhaps some

among them had read the Great General’s works and realized their folly, or maybe they were simply confused their prey had stopped running.

“Wondering on its purpose only kills its utility,” Ma Wei Sheng whispered to himself while moving to meet the mob of thirty armed killers.

So, this is the introduction chapter, but as this is a supplement to an existing corebook, this game doesn’t have to bother with explaining what an RPG is, and we can instead get right into the interesting stuff. This chapter is dedicated to giving some essential background info about the game, elaborating on the genre, and just explaining what the hell this game is.

So, first is a Glossary of Terms. Thankfully, there are neither dry mechanical terms, or nonsensical White-Wolfisms here, instead it exists to explain concepts that your typical person might not understand, especially terminology borrowed from Chinese. So, I’ll recreate in in a condensed form here so we can all benefit!

-

Adherents of the Tao/Dao This is the Tianxia version of Taoism/Daoism (The words are pronounced the same, just the romanized spelling differs based on whether you use Wade-Giles or Pinyin romanization). Real world Taoism is incredibly complex, mainly because it’s been around for ages, is incredibly syncretic so it has gotten mixed in with every other religion, philosophy, or spiritual belief in Chinese history, and has various differing sects and schools of thought. In brief, Dao, literally “The Way” is the concept living one’s life in unity with the natural flow of the universe. Generally this means living a balanced harmonious life of simplicity in sync with the flow of the universe. In Wuxia if you do this well enough you become an immortal and get magic superpowers.

Chi Also spelled Qi, literally “Breath”, is the concept of an internal energy, life force, etc. While it has many varied meanings in medicine, philosophy, and religion, in the context of wuxia stories it’s what lets you do crazy physics breaking kung-fu stuff just by working out real hard. The Force from Star Wars is basically qi, for these purposes.

Da Jiang “Great River”, a very large and important river that flows through southern Shenzhou. While it’s not part of the setting detailed in this book, it’s considered important enough to Shenzhou as a hole to mention.

Emperor The ruler of Shenzhou. Also known as Huangdi, “Yellow Emperor”, or Tianzi, “Son of Heaven”, he or she is believed to be ordained by heaven to rule all the lands of the world. The Emperor governs through a complex bureaucracy of ministers, governors, and officials.

Eunuchs Someone who has had their sex organs removed. In Shenzhou this is not surgical, but is done by mystic ritual that makes the subject sexless. They serve as important ministers and imperial officials, and are often portrayed as villains in Chinese media. The closes western concept would be the idea of the “Evil Vizier”. Historically Eunuchs were prominent in certain dynasties as important functionaries, especially in the Imperial Court. This was both because, as they could not have children, corruption, nepotism, and treasonous ambition was less prominent and because they couldn’t get up to anything freaky with the Emperor’s wives.

Followers of Bodhisattva Also known as Bodhists, they are the Tianxia equivalent of Buddhists. The philosophy is all about seeking enlightenment, peace, and the alleviation of suffering by rejecting material attachments and cultivating an awakened mind.

Gong Artisans and Craftsmen, part of the middle class of Shenzhou.

Jade Road An important trade route, named for the mining and production of jade goods, which it serves as a major trade route for. It stretches from the western border all the way to the eastern cities.

Jianghu Literally “Rivers and Lakes” the term refers to many concepts in chinese culture. At its broadest, it simply means the culture and community of those whose way of life is not part of traditional society. In modern contexts it’s essentially the same as the english term “Underworld”, representing the culture of criminals and those who live outside the law. In Wuxia, Jianghu refers to the sub-culture of vagabonds, adventurers, and martial artists, those who live on the fringe or outside of traditional society. Another term for the same concept is Wulin “Martial Forest”.

Jiangzhou “Border Land”, the province of Shenzhou detailed in this book. It’s the far western frontier of the Empire, and is largely lawless.

Kung Fu A generic term for all styles of Chinese martial arts.

Legalism The official religion of the Empire of Shenzhou, and the Tianxia equivalent of Confucianism. Essentially, a philosophical school of thought and religion that emphasized unity with Heaven by moral living according to a divine order or hierarchy. As concerned with how proper governments and societies function, as it is with personal ethics and morality.

Nong Peasants and farmers, the lowest traditional social class in Shenzhou.

Security Companies Businesses that hire out mercenaries and bodyguards, specifically for protection of people or property. Often clash with government authorities, they range from heroic protectors, to bandits with pretensions.

Shang Merchants and traders, part of the middle class, but the wealthiest can have as much power as the elite.

Sifu “Skilled Person”, an honorific for teachers. Common translation would be “Master” or “Teacher”. While it can apply to any sort of teacher, in wuxia it’s primarily applied to Kung Fu masters.

Shen The collective name for the people of Shenzhou, though most people don’t call themselves that. Identifying instead by village, province, or family. People and objects from Shenzhou are called Shenese.

Shenzhou “Divine Realm”, the proper name for the Empire and primary setting of Tianxia. The name was an archaic term for China.

ShiNobles, Scholars, and high officials. The elite and powerful upper class.

Silk River A major river in Shenzhou, which passes through Jiangzhou before flowing east to the sea.

Tianxia “Under Heaven”, a concept in Chinese political philosophy referring to the Chinese Empire, the entire world, or the idea of cultural unification. Closes western concept would be, it’s the Chinese equivalent of “Manifest Destiny”.

Wuxia Literally “Martial Hero”, sometimes translated as Knight Errant or Wandering Warrior/Swordsman. This is both a genre, and a type of character or profession found in said genre. Essentially, Wuxia are highly skilled warriors who operate outside of traditional society.

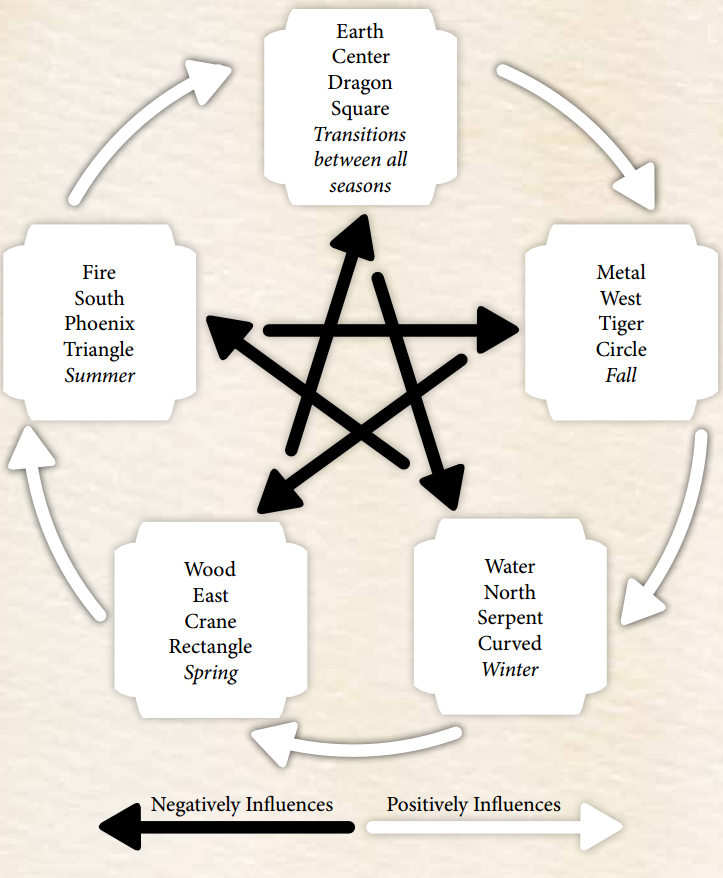

Wu Xing A five part concept of connected elements, colors, directions, seasons, animals, etc. A framework of thought and theme found throughout chinese culture. It has been slightly modified to make it easier to remember and work with in the game.

Yang Positive forces. Proaction, heat, light, and masculinity are represented by Yang.

Yin Negative forces. Reaction, cold, darkness, and femininity are represented by Yin.

Yi “Outsider” or “Barbarian”, a term for those not from Shenzhou, or who are not seen as part of Shenese society at all. The term Hu is also used, primarily when referring to tribes that live near the borders.

Zhongshou “Center Land”, the Imperial Province, where the capital and Emperor’s Palace are. Often used as a term to refer to anywhere with strong Imperial presence, not just the province itself. It’s located on the eastern shore of Shenzhou, but is considered to be the center of the empire.

Whoo! Now that’s out of the way, and we can continue!

Next is the actual introduction, which gives an overview of each chapter’s contents, and explains the design philosophy of the game. There’s no need to go over this though, so I won’t.

Next is actually something useful! The Cardinal Rules of Campaign Customization. See, Fate is a toolbox game, it’s a bunch of mechanics and parts that you are encouraged to mix and match and customize to your taste. Tianxia just adds some new mechanics to support wuxia genre games, so they include some guidelines about how to work out customizing and making things in game in a pretty useful four stage process:

-

Step One: Talk it Out Basically, if there’s doubt about the best way to represent something in the game, the GM and players should talk out how each wants to handle it. It lets everyone get their own desires out there, as well as go over any issues or concerns that might pop up.

Step Two: Figure it Out Work out exactly how the changes or modifications you want to make should work, and clear it with everyone so everybody knows how the changes work and is okay with it.

Step Three: Now Go Forth Basically, once you got a general idea, implement it and don’t get hung up too much on the ganges. You can change it again if things don’t work out, it’s more important to keep playing and having fun instead of getting obsessed about the setting or mechanics and killing the game’s momentum.

Step Four: ...and Kick Ass Basically, if things aren’t going how you like, just make the changes on the fly and keep up the momentum, demonstrating what you want to happen instead of stopping the game to go over everything every time an issue comes up. Keep it dynamic and generally things will work out, and you can stop to discuss if there are problems.

Who are the PCs? And What do you Need to Play?

I’m rolling these two sections into one, just because they’re short. THe default assumption of Tianxia is that the PCs are playing wuxia, wandering martial arts warriors embroiled in the struggles of the hidden world of the Jianghu, with players growing in prominence, power, and importance over the course of the game. Equally valid though is playing characters more part of traditional society, in fixed locations or tied into important elements of the setting.

As for what you need to play, is just helpful advice for necessary stuff to get. You need a copy of Fate Core to play, a set of Fate/Fudge Die, though the game does support others, a character sheet for each player, a way of keeping track of Fate Points, a pack of Index Cards, and some way of tracking initiative. They suggest players just sitting in initiative order to make it super simple.

Wuxia, Kung Fu, and Genre

This is a genre game, so it’s kinda important to define the genre’s we’re working with. Now, Tianxia is, by default, a blend of two related genres: Wuxia and Kung Fu. These two genres are related but distinct, and if you’ve seen enough martial arts movies you should be able to know the difference even if you’ve never been able to articulate them. While both are focused on the idea of martial artists, and solve their problems via acrobatic violence, the scale and existence of the fantastical are the primary ways to tell the two apart.

Wuxia stories are big. The characters can often do superhuman feats of athleticism and combat, fantastical or magical elements are much more common. Kung-Fu stories on the other hand are generally much smaller scale. There are generally set in grounded historical settings, the stories are small scale and focused on personal issues, and the martial arts are purely practical and what actual humans can do.

The way the game supports a mix is simple: The feats of the characters are very wuxia, with superhuman feats being common once you get some of your skills up there, while the setting favors more down-to-earth grounded and small-scale stories. To change the focus, simply dial up or down descriptions of character actions as desired, and focus on different aspects of the setting.

What’s in a Name

Chinese naming can be complex, especially with how varying translation conventions render names. Some use straight chinese names in the appropriate format, others reverse the family and given names, others fully translate the names into ones that sound more like poetic titles, and others still mix the two getting names like Silken Wei and Iron Tsang. Tianxia uses all three, but favors the part-english part-chinese names as it stays evocative of the setting, but it’s a lot easier to create memorable names for English speaking players.

The Wu Xing

Essentially, the Wu Xing is a major part of chinese culture, and is a motif repeated constantly throughout affecting everything from art and music, to medicine, interior decorating, martial arts, military strategy, religion, philosophy, fashion, etc. etc. etc.

It’s important. Tianxia recommends using the Wu Xing as a source of inspiration, a handy way to create themes and concepts that ring true with the setting. By using the colors, animals, elements, seasons, etc. as inspiration for settings, characters, and events. Basically, don’t get obsessive about it, but injecting a bit into your game can add some fun flavor, and help people brainstorm ideas and give flavor to the setting.

So, that’s it for the intro! Next time Shenzhou and Jiangzhou: The Setting Part 1!’