The Play’s the Thing by unzealous

Post

Original SA post

The Play’s the Thing is an interesting rpg. It’s not a superb example of game design, or a massive budget, but it has a fun premise and provides an excellent change of pace to the more serious minded RPGs out there. The basic premise of the game is that the players are all actors in a play. They jockey for parts and will likely (definitely) try to do some improv when they’re up there. It might be because they forgot their lines, or they didn’t pay attention to the script. It might be because they want some more time on stage and are willing to do TERRIBLE things to the plot in order to get their way. So, if you’ve ever wanted to be the Tybalt who decides to kill Romeo in the duel, to be the more reasonable MacBeth or to just straight up introduce martial arts to Hamlet, it’s up to you.

It starts like many other RPG books, a brief history of what inspired the game, a section describing the act of roleplaying. It does have a section which I appreciate which gives a very explicit overview on what the game is about and how to play it.

quote:

“In my game, the players portray actors who have been called by the Playwright to rehearse a Tragedy, comedy, or history. The actors must follow the style, plot, and lines they are given, but will, of course, attempt to improve the play by offering their own suggestions and improvising as often as they can get away with it.

The Playwright, on the other hand, wishes to see his work brought to life by the actors, but is bound by their egos, desires, and failings. he must inspire them to greatness, and cannot let them derail the entire show. he has to use their new ideas to improve the show without ruining what made the show great in the first place”

The game itself largely follows the structure of a play. The Playwright acts as the director of the play. Each game is divided into Acts. The Players take the role of Actors, are cast in Roles, and will probably (definitely) do what they can to change the play to their liking. In my experience this can range anywhere from adding an extra soliloquy as a scene ends to showing up on stage in cardboard power armor. It’s really going to depend on the group. The Playwright acts as a sort of adjudicator, doing their best to make their dream play a reality despite the continued efforts of all the actors. Story points are the main resource in the game. You get them for following the play as it’s currently going, following the themes and plots as they’ve developed, and can spend them to make changes to the play. They are awarded by the Playwright and as a Playwright it’s expected you’ll be fairly liberal with them.

The Actors

Most of the players will be Actors. All you need for the actor is a name, a rough idea of what kind of person they are and what they want out of the play. One might want as much stage time and lines as possible. They want to be the center of attention, always. Another might only be here because they’re bored and are interested in doing the absolute minimum. Another might be the aspiring Oscar winner who treats the play with reverence and acts their heart out in any role.

Actors also have Chops which act as their stats and reflect the ways they are best at changing the play. We have

Logos: This deals with your ability to change events or the way they unfold. This is changing the results of a duel or an ambush

Pathos: This is your ability to affect parts and plots. These rolls let you add plots to characters or ignore others. For example convincing Juliet that Romeo isn’t that interesting.

Ethos: This is how well you can affect the props and setting of the play. This is how you pull out the hidden stage knife or convince the Playwright the play would be much more interesting on the moon.

You have 6 points to allocate to these three stats and none of them can go over 3. It all depends on what you’d like to be best at. You might also notice that these are fairly broad, and might even overlap or require adjudication in certain circumstances. At that point it’s best to come to an agreement with the playwright.

So, at this point you’re going to pick your actor Type, which acts like your class and represents the kind of person you are on and off the stage. You are given an Onstage Ability which you can use while you are currently in the scene, an Offstage Ability that can be used when you aren’t, and a Direction. A Direction is something the Playwright can ask you for that you must do, and can often be a source of additional Story Points. They can, however, only ask once an Act. For example we have:

The HamThis is the kind of person who is invigorated by the audience, for good and bad. They live for the applause, the tears, the laughter, all of it.

Onstage Ability: They may yell “Cut!”, enabling them to suggest a change, without having to spend a story point.

Offstage Ability: They may spend a story point to compel an actor on stage to call for you. They can spend their own story point and refuse but if they accept they gain your story point.

This is important because under normal circumstances if you are offstage you can’t simply walk back on. This allows them to come back on stage at a time of their choosing, even if it’s wildly inappropriate for the play. For example if a sinister group is planning the assassination of the actor he can use this ability to hop into the scene which would make things rather awkward but certainly entertaining.

Direction: Once an act, when directed by the playwright, you must deliver a soliloquy. It doesn’t matter what you’re doing on stage, if you’re the king or the janitor, you have to drop everything to deliver a speech to the audience about what your character is thinking about.

We’ll get into these mechanics in more detail further on.

The Basics

Once you’ve created your actor it’s time for Casting. The Playwright will introduce the play, either one already established or one they’ve made themselves. The Playwright should give out a Synopsis of the play as well as a Cast List and give everyone 5 Story Points to start out with. The Playwright will start with a Name for the character, a Part, their Plot and a Prop.

Parts are the jobs or titles their character possesses. It represents the basic motivations and duties of the character. Each Part comes with a description of what it entails as well as an Invoke and Compel. An Invoke can be used when you want to change the play in a way that would be in character and gives you bonus dice to the role. A Compel is something the other actors can use to entice you to stay in character through the use of story points. Yes this is similar to FATE.

There are several example Parts in the book.

The Exile

A stranger in strange lands you either cannot return to your home or are forbidden to.

Invoke: Gain two dice when acting against those who exiled you

Compel: You are alien to this place, act like it.

The Knight

You follow a lord or ideal with dedication and honor, even against your own interests.

Invoke: Gain two dice when fulfilling your commitments

Compel: You cannot act against your liege’s will.

There are others like Ruler, Commoner and Nurse and are outlined similarly. When making these for a new or existing play they’re fairly easy to create which is helpful.

Plots are similar to Parts but focus instead on how you relate to another character. These can be mutual like between a teacher and student, or entirely one sided. These must relate to other characters in the play and can’t be referring to people who are only alluded to. Like Parts these also have Invokes and Compels and can be used to influence the play to your liking and influence you to act more in character.

For examples there are

Daughter/Son

You are the child of another character and, regardless how you feel about them, this is a meaningful bond.

Invoke: Gain two dice when dealing with your parents

Compel: You must obey the head of the family regardless of how you feel.

In Love

You are in love with someone to a degree which no one else could fathom.

Invoke: Gain two dice when pursuing your love

Compel: Love can make us do foolish things

Props are items used for dramatic effect on stage and give a die bonus for specific tasks. Unlike Parts and Plots these aren’t associated with a specific character. If a knight drops his sword the queen can pick it up and use it herself. Examples:

Crown: Add one die when acting as the rightful ruler.

Coin: Add one die when convincing someone to follow your plan.

Places are specific areas of a Set and act similarly to props though with less rigid guidelines on what situations will give the actor a bonus. For example the Set might be in a castle and through the play itself as well as edits you might add a feasting hall, a throne room, a dungeon and really any place that might conceivably be in a castle.

Finally, once you’ve been given your roles the Playwright will give you a few Lines that your character will say during the course of the play. These are the well known lines that even people unfamiliar with Shakespeare probably know. "O Romeo, Romeo! Wherefor art thou Romeo?" If you manage to to use one in an appropriate scenario you get a story point. If you do so with gusto, brimming with emotion and chewing the scenery like your life depended on it you might get anywhere between 3 to 5 story points.

Knowing what these are we can now talk about players choosing these at the beginning of the play. As written, once the players have their Actors chosen and filled in their Chops the Playwright will introduce the play with a brief summary and provide a complete cast list of all the available parts. The Playwright will then start at the top with the Role’s Name, Plot, Part and associated Prop, as well as a few story points that are awarded to whoever claims it. Players now go around the table and can either Pass on the character, Claim the character and the story points, or Bid on the Character.

Bidding on a character is a way of adding to it, making it more complex but potentially more interesting to play. When you Bid on a part you can add an additional Plot or Part and add an additional Story Point to whoever ends up playing it. If there are more parts than there are players the Playwright can read for those parts during play.

If a Character goes around twice with no one claiming it it will be read by the Playwright during the game.

An Important note. You might end up with a Role which is riddled with Parts, Plots and Props, enough to make actually playing it quite daunting. For better or worse you are limited to the amount of these you can bring on stage and invoke during any given act.

You can’t have more Parts than your Logos.

You can’t have more Plots than your Pathos.

You can’t have more Props than your Ethos.

The unused props are going to sit in a trunk offstage. The unused Parts and Plots however can still be invoked by the Playwright and the other actors. The characters themselves don’t change based on this either, with the book example being a King still being the King regardless if they’re using the Ruler Part or not. While they won’t be able to spend a Story Point to gain the extra dice for invoking the Part they can still be targeted by it’s Compel.

Before the game begins but after Roles have been chosen the actors also have the option of adding their own Parts and Plots to the character under the justification that they’ve seen this story before and already know what they’re supposed to do. Doing so does require the expenditure of Story Points though.

Coming up: Acting out the Play!

Post

Original SA post

4. The Play

Alright, you’ve got your actor, you’ve got your role, you’ve picked out the plots and parts and props you’ll be using first. The Playwright sets the stage and scenery and gives an outline of the basic story that will be occurring in this act. What’s next is up to the group. By and large this game is about improvisational acting. Be as hammy as you want, have long speeches and soliloquies, chew the scenery, things like that.

An important thing of note is that if you’re off stage you can’t get on unless you’re specifically called to. If the actors on stage call on your character you can jump in without cost. Otherwise you can spend 3 Story Points at which point you can just hop on no matter what is happening.

The Playwright might periodically give instructions or reminders of how things are supposed to go, but of course if that were all to this game it wouldn’t be very entertaining. That’s where edits come in. Edits are the meat and potatos of the game mechanics. Its how everyone can make changes to the play as it's progressing, changing the plot, the set, whatever they fancy.

Edits

If the Actors start straying from the script but want to keep going they can spend a Story Point and yell “CUT!” From this point a few different things might happen. If the Playwright likes the change he can simply accept it and the play will now carry on in this new direction. If not they can decide to FORCE AN EDIT, which is where this game slows down but also the part that generates a lot of the enjoyment.

First, you have to figure out how big a change this is going to be.

A Trivial Edit is changing the name of someone or where someone else is standing, something small that won’t really impact the plot as written.

A Minor Edit is one that will or has the potential to change the narrative such as changing the set or forcing someone off the stage.

A Major Edit is one that’s going to greatly change how the story is going to play out. These are things like a character dying, a revelation which might add a Plot or Part to the story like Hamlet having an Evil Twin or Romeo actually falling in love with Tybalt.

Once you figure out how big an Edit it will be you need to figure out which of your Chops (Ethos, Pathos, Logos) you’ll be using depending on what your Edit will be affecting. Then you add up bonus dice from invoking a Part or Plot and/or for having the appropriate Prop or Set, though you only get one of each for any given roll. The example from the book lays it out rather nicely.

quote:

“The Earl of Kent says “I will change the King’s mind so that he does not banish Cordelia (+2 Logos). It is only right that I do so, as I am his Knight (+2) and his Friend (+2). I will call upon the Formal Court, as I am making my plea formally known (+1), and I am willing to donate a bag of Coin to the kingdom as a symbol of my loyalty to the throne (+1). I get eight dice.“ “

Of course someone else might not be on board with your edit. Whether they want to keep the play as pristine as possible or they’d rather see it play out according to their own machinations they can spend a Story Point and form up a dice pool using the same guidelines. Whoever rolls higher, assuming they beat the target number, has their Edit made into the play.

Assuming the Actor has rolled high enough the Playwright will narrate how their change has affected the scene and the direction of the play and will resume play usually by calling “Action!”

Another important thing that can come up during the play is being Wounded or Poisoned in the play outside of the script. This is always an important event to the story and should be treated as such, but they will be fine if they get through the act. Being Wounded or Poisoned is a Minor Edit while its more severe counterpart of Mortally Wounded/Poisoned is a Major Edit. If an actor is Wounded or Poisoned a second time, or just straight up Mortally Wounded or Poisoned they will die, but not before they’re allowed a lengthy death speech. Between acts they can be Cast in a new role by the Playwright.

The last act of the play is similar to how the others have been described with the exception that the Playwright should also give an idea of how the Play is supposed to end. There’s likely going to be some singular events that need to happen to keep the play in line, there needs to be the death, the marriage, the speech, something like that. Of course this might have changed during the course of the Play so it’s up to the Actors and Playwright to figure out how to hammer out an ending with whatever's happened so far.

4.5 The Actors (Now with Context)

So now that you know how the rules work the types of Actors will make more sense. We’ve already discussed The Ham so now we can take a look at some of the other types.

The Lead is the thespian, the person in it for the love of the craft. While they take their job seriously that doesn’t mean they’re stodgy or dull, they just don’t let things distract them from their art.

Onstage Ability: You can spend a Story Point to bring an additional part onstage with you beyond the limit of your Logos. This can give you more options when looking to change the story to your liking by acting as an additional avenue for bonus dice.

Offstage Ability: You can spend Story Points on behalf of another actor. If someone has a good idea for an Edit or would love to use their ability but simply can’t at the moment you can graciously give them a bit of your prowess.

Direction: At the Playwrights direction you must stand and face a source of danger whether you really want to or not. If you had the bright idea of avoiding a duel you know you’re supposed to lose? Tough. Face them like the Actor you are.

The Villain always seems to look like they’re up to no good. No matter what role they’re playing people expect deception from them. They love the scenes where they can backstab and where things escalate to brutal (stage) violence.

Onstage Ability: You can spend a story point to immediately wound or poison another actor without requiring a roll. This may not seem like much but remember that everyone here is an actor. If you’ve been wounded you should play the part or else you’re kind of negating the premise.

Offstage Ability: You can spend a story point to whisper a nasty rumor to someone on the stage, likely one concerning another Actor. If you spend an additional Story Point they must believe the rumor is true and act accordingly. Like their onstage ability this relies on participation from the other parties but should be embraced as such.

Direction: When directed you cannot show mercy or justice to someone, no matter how insignificant or reasonable the request is.

The Ingenue is the person new to the craft who’s looking at this new world with wide, innocent eyes. They project a sort of naivete that others often find charming and even enthralling.

Onstage Ability: You can spend a Story Point to reroll a failed Pathos roll. If you’ll recall Pathos rolls are for Edits concerning the actions of the Actors.

Offstage Ability: You can spend a Story Point to allow someone else to reroll a failed Logos roll, which are used to effect the set and the setting.

Direction: If the Playwright asks you must put yourself in danger somehow, either the result of someone else’s actions or your own.

5. The Playwright

So this is the Dungeonmaster, Storyteller, Referee of the game. Your job is to keep things moving, to keep people engaged as best you can and look upset when they inevitably take your play and turn it into something entirely different. The book does give some suggestions on how to make the game run better and I think they’re quite important to this game in particular.

1. Be Prepared. This isn’t like other RPGs where you can just improv your way through the whole thing. You’re going to need a Cast List with Parts and Props set up ahead of time unless you want your players to twiddle their thumbs while you figure things out. Thankfully the book itself has pre written scripts for several plays that have done almost all of the heavy lifting for you which is extremely convenient. Especially if you want to play on short notice.

2. Don’t plan too much. This is a game where much of the fun comes specifically from things going off the rails, trying new things, letting people explore the space as it were.

Encourage your players to engage. This particular entry is important because it explicitly encourages doling out story points whenever people are engaged. Always ask if they’d like to make an Edit and encourage them to do so, after all it’s the crux of the game.

3. Use Directions and Compels. Every Actor type has a direction which can be used to help keep things moving. Using these not only engage and motivate the Actors it also provides them with Story Points they can use at their own discretion. The Author states they use them whenever possible which, again, is nice to see explicitly stated.

4. Focus on the Ending. You know how the play is going to end. In a death, a marriage, a huge speech, and you should be angling towards that during play. If they try to avoid the obvious fate it's not out of sorts to have their plans suddenly turn back on them fulfilling the prophecy they sought to avoid.

6. The Plays

The next section gives some advice that’s more specific to certain categories of Shakespeare's plays. It leads with an overview of the genre and follows with tips specific to be the Playwright for that sort of play. And this is also where I reveal my ignorance about Shakespeare’s plays as I largely summarize what’s in the book but if anyone has any more insight or information by all means post away.

Comedies generally focus on an entangled romantic relationship between highborn characters that ends in marriage. There are problems but they generally aren’t life threatening. There are additional lowborn characters that have a plot that intertwines with the lovers and the lowborn also serve as a source of slapstick humor and innuendo. The ending will generally be happy even if it’s not “and they lived happily ever after”.

As far as running a Comedy goes the player’s probably aren’t going to have a problem with the comedic parts as people tend to do that even in serious games albeit not always in character. Reward story points regularly for one-liners and pratfalls. If they try to avoid the marriage or marry someone else that’s fine. It’s ultimately the premise of the game itself and should be expected if not encouraged. With these plays your main job as a playwright is to ultimately keep the mood lighthearted and jovial.

Tragedies focus on how one’s actions can lead to one’s downfall. Even if it’s prophesied that they will come to a tragic end it is ultimately their decisions that lead to their undoing. These plays are very focused on the main plot. Terrible things will happen to those who deserve it and to those that don’t. There will be blood, and while not everyone may die it’s almost guaranteed the protagonist isn’t going to live through the end.

These plays can be a bit demoralizing, knowing how the ending will be riddled with death and destruction and their fate is all but certain but that’s no reason not to have fun doing it. The stakes in these are always high and people will probably take very little coaxing to start planning to murder each other off. And remember, when you die you always get a monologue.

Histories are about important events, usually about the English Monarchy, and then dramatizing it for a play. They tend to take some artistic licenses in portraying figures as good or evil depending on the play. These are known for onstage battles, long speeches and the replacing of one monarch with another.

With these plays there’s a lot less set in stone in terms of tone. They could be tales of coincidence and comedy or tales of hardship and sacrifice. While the play should definitely focus on the titular character it’s more up to the Actors to how they’re portrayed than the other genres. The main focus of the play is politics and all that includes. Scheming, plotting, murdering, rebelling are all part of the game.

There is one last small section here with a few frequently asked questions. Nothing spectacular but it does bring up a few important points. First is that, as the Playwright, you should be liberal with story points. This isn’t a game about survival, it’s about acting and collaborative storytelling and everyone should have the opportunity to participate. The second part concerns an eventuality that can happen in any game where death features, which is “What if my Character dies early?” Its important to know that from the perspective of both the Actor and Playwright this isn’t the end of the world and you won’t be spending the rest of the game in the quiet corner. The player who killed you might have a plan that would be interesting to see played out. And the Actor in question can either show up in another role or come back as a Spirit or some other form of undead, both of which factor heavily in Shakespeare’s plays. While not stated, if it seems like someone is dead set on just murdering everyone for no reason they’re just being an asshole and they should probably be talked to.

So, the last third of the book is pre-written scripts for quite a number of Shakespeare’s plays. They’ve written up the Cast, doled out Parts and Props and done all the heavy lifting for you if you just wanted to jump in and start playing. It seems a bit unfair to do what would essentially just be copy pasting a large chunk of the book and what likely took a good amount of work, so instead I offer an alternative.

If anyone has any suggestions of a (preferably fairly short) play they’d like to see written up and made ready for play let me know and I’ll do my best to get it to a place where you could run a game with it.

Post

Original SA post

6. Example Script

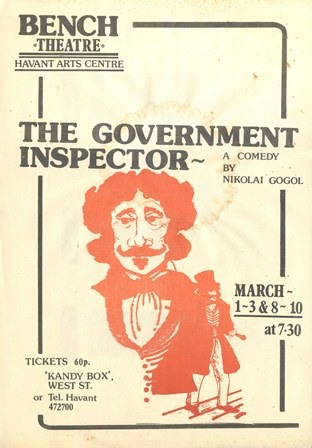

The Inspector General (AKA the Government Inspector)

By Nikolai Gogol

I'm going to go ahead and apologize in advance if I've fucked something up. Hopefully I'm doing the play justice

Casting List

Anton Antonavich Skovznik-Dmukhanovsky (Who I will refer to as Anton or the Governor from here on out)

Part: Governor

Invoke: Gain two dice when performing your duties

Compel: Make sure the inspector is tended to, they control your future.

Plot: Accomplice

Invoke: Gain two dice when trying to cover up your misdeeds

Compel: You divulge knowledge of someone else’s transgression

Prop:

Money - Add a die when using money to convince someone of something.

Hlestakov - A junior Clerk

Part: Fraud

Invoke: Gain two dice when acting on your perceived authority

Compel: You must act like the high ranking, high class person you clearly, definitely are.

Plot: Lover (As in the book)

Prop: Letter, gain one dice when spreading secrets.

Osip - Hlestakov’s servant

Part: Commoner

Invoke: Gain two dice when navigating the lower classes

Compel: You are hardened to the suffering of others

Plot: Servant

Invoke: Gain two dice when obeying your master

Compel: You must obey even if doing so would be awkward or even dangerous.

Anna Andreyevna - Wife

Part: Maiden

Plot: Mother

Prop: Beautiful Outfit - Gain a die when using your dress to impress.

Ammos Fedorovich - Judge

Artemy Flippovich - Supervisor of Charitable Institutions

Luka Lukich - Superintendant of Schools

Ivan Kuzmich Shpekin - Postmaster

These four characters occupy a very similar space in the play so it’s easier to make a set that fits all of them

Part: Commoner

Plot: Accomplice (See the Governor)

A prop would likely relate to their profession and give them a bonus die when doing something in that vein. A symbol of authority for the judge, a book for the school superintendent etc.

Act 1

Anton, The Governor, has a meeting with several government officials including Ammos, Artemy and Luka. They have been alerted that an Inspector will be coming to the town undercover, which has them quite worried. They go over their various indiscretions and come up with ways to cover them up. They are alerted by some locals that someone strange showed up several weeks ago and the Governor firmly believes it is the inspector who has come before he could adequately prepare. Anna and Marya enter, very curious about what is happening. The Act ends with her giving orders to tidy everything in the house and learn anything about the visitor.

Act 2

Osip laments his current situation which has been caused by Hlestakov living far above his station and spending money faster than he gets it. Hlestakov enters and demands Osip fetch him food despite the hotel no longer giving them credit. Osip argues with one of the staff while Hlestakov complains of his hunger. When a servant brings a plain meal Hlestakov yells at them for it not being of better quality but eats with voracious hunger. The Governor enters believing Hlestakov to be the inspector while Hlestakov believes the Governor is here to arrest him. They both panic but Hlestakov’s bravado convinces the Governor that he is the inspector. The Governor invites him to stay at his house and give him a tour of the city.

Act 3

Anna and Marya wait anxiously at home when they see Dobchinsky come bearing news. He tells them of the Governors encounter and gives them a note informing them to expect a guest and to get wine ready for the evening. Both women become very excited at the prospect of having prestigious company. Hlestakov and Anton arrive at the police station having visited the hospital off screen. Anton expounds on the positive qualities of the hospital while Hlestakov tries to find a game of cards to play. The two arrive at the governor's house for lunch during which Hlestakov makes numerous outrageous claims to his status which the people all believe. Anna and Marya are particularly smitten. The Governor worries that getting Hlestakov drunk made him more truthful and that everything that was said was accurate. He sets guards at the door to make sure no one enters the house.

Act 4

Artemy, Ammos, the Postmaster and Luka meet to discuss ongoing methods of keeping Hlestakov happy. They decide to approach him individually. Ammos awkwardly tries to bribe him which Hlestakov believes is just his way of being generous. The Postmaster meets with him and Hlestakov asks to borrow some money which the Postmaster also does believing himself to be bribing the man. Luka comes in but is immediately confused by Hlestakov asking his preference in women. Hlestakov then asks for a loan which Luka gives before exiting. Artemy enters and begins to discredit the others, writing down their misdeeds which he gives to Hlestakov before Hlestakov asks Artemy for a small loan as well. Several Merchants force their way in and begin telling Hlestakov of their mistreatment by the governor. He asks them for a loan and they give it believing he will help them. Other citizens come forward with similar complaints until he has Osip force everyone else out. Hlestakov has a confusing encounter with Marya, confessing his love for her, before being discovered by Anna, who he also declares his love for. This confuses the two before the Governor enters, doing his best to dismiss the complaints from the citizens before learning of Hlestakov seeking Marya’s hand. Hlestakov and Osip leave, telling the Governor they’ll be back in a day or two.

Act 5

The Governor relaxes with Hlestakov gone, believing himself safe. He talks with Anna about plans for the future believing he’s made a great ally with the inspector marrying his daughter. He invites the merchants who complained in to chastise them. The other characters all come to congratulate Marya for accepting the marriage proposal. Anna recounts the events though saying the compliments Hlestakov gave were to herself and not Marya. More congratulations from the characters to Anna and Marya. The Postmaster enters, having opened one of Hlestakovs letters talking at length about the town. The Governor forces him to read it aloud and it is filled with criticisms and mockery of the characters he’d met. The Governor is in a terrible state and begins to blame the others for all the terrible things that have happened.

Ending:

During a heated moment a Gendarme enters and tells the Governor the Inspector has arrived and demands his presence at once.

Its not 100% complete. It’s still missing notable lines but given my lack of familiarity with the play that’s something probably done by someone more familiar with it. Its possible to come up with an entirely different synopsis of the play or its characters and that’s okay too. Regardless if the play is a tragedy or a comedy this isn’t a game to be taken seriously. At least not outside of the game itself. Admittedly I was completely unfamiliar with the play beforehand so I hope I did an adequate job of turning it into a workable script for a game.

6. Romances

Back to the book itself the last section is about the Romances. These are much more fantastical than his other works and included magic and music and larger than life characters.

quote:

Like comedies, most romances end in marriage, but the context is markedly different. rather than celebrating the existing social order through the bonds of matrimony, the marriage at the end of a romance reunites two communities or individuals who were driven apart in the past, healing the social fabric that had previously been torn asunder. The marriage affirms the social order, but simultaneously reveals the fragility of the society in which it takes place.

The Mask is someone who uses their body as a tool more than any other person. In one moment they might have the delicate grace of a ballerina and the next the loping gait of a cripple. Think Charlie Chaplain or Mr. Bean. This is definitely the actor type for the person who likes describing their character’s actions.

Onstage Ability: Their presence and movements can be unnerving, even to their fellow actors. You can spend one story point to force an Actor to reroll their Edit. While this seems confrontational (and it is), its not really any worse than any of the other ways one might contest an edit.

Offstage Ability: The Mask is always watching and listening. Spend a story point to hear a secret from the shadows.

Direction: At the Playwright’s request the Mask must tell their story by describing their actions. It sounds like an interpretive dance of sorts, or maybe some miming.

So that sums up The Play’s the Thing. Not an amazing RPG, not one you’ll run a year long epic campaign with, but a breath of fresh air and a fun diversion from a lot of the more serious minded RPGs.