Runequest 2E by Spiderfist Island

A History Lesson

Original SA postA few years back I made an abortive attempt at reviewing the 3.5 D&D supplement

Magic of Incarnum

. To be honest, I don’t remember why I bothered to start the review, or why I decided to drop it so quickly. So, I’m going to continue to not do that and try reviewing something else entirely.

Those shapes scattered around the title sure look like important things!

A History Lesson

So, let’s briefly pretend that it’s 1978. D&D is just 5 years old (depending on what metrics of where its existence as a

Chainmail

supplement ended and it being a “standalone” product began). The RPG industry is so new that it hasn’t yet been distinctly separated from the wargaming scene. The vast majority of new RPG products are responses to or collected houserules for D&D- a situation that continues to this day. In July 1978, one of these new RPGs debuts at the Origins convention. It’s called RuneQuest and is the first major product by Chaosium. Runequest proceeds to win several awards such as “Outstanding Miniatures Rules,” and had an unconventional setting, Glorantha, attached to the game.

The first edition of Runequest was, however, a bit… spotty. In the rush to get it out before Origins, there were numerous typographical errors, up to misspelling the company name as “Chasium.” After the convention, a second edition was written with minimal difference in the rules and with much better production values.

In late 2015, a successful Kickstarter occurred aiming to re-publish RuneQuest 2E as a celebration of the 40th anniversary of Chaosium. The republished version of RuneQuest 2E has the later errata directly included into the rulebook, but otherwise keeps the text the same. Since I am a lazy millennial who couldn’t be bothered to be born until after the Cold War ended, I’ll be using this new printing as the reference text for the review.

Why Review RuneQuest 2E?

RuneQuest is a pretty significant RPG for several reasons.

-

It’s the first major RPG to use a percentile system for basic target checks.

-

It’s one of the first RPGs to have

any

conscious attempt at a unified resolution system.

-

It’s the basis of the Basic Role-Playing system (BRP), which itself was used for Call of Cthulhu.

-

It’s one of the first

victims ofattempts at creating a verisimilitudinous combat system in a fantasy RPG.

-

It’s the first RPG set in the world of Glorantha, an obscenely detailed bronze age fantasy setting that somehow has managed to retain a devoted fanbase over decades.

In short, RuneQuest 2E is a time-capsule of the earliest days of the RPG industry and game design– it’s very much a response to D&D, but it has many design innovations of its own. All games made by Chaosium, and even all percentile-dice systems, trace their design lineage in some way back to Runequest.

This review is a partially-blind read of RuneQuest 2E. I’m not going to go word-for-word over the rules and text, but I’ll do my best to summarize the mechanics and only quote notable passages. I'm also fairly familiar with some aspects of Glorantha, though I don't know how much of the setting has been changed in the years since RuneQuest 2E came out. It’s my goal to do a good job of highlighting the interesting and notable parts of Runequest while also clouding things with heavy editorializing.

Let's Read Page 3: A 40-Year Late Text Deconstruction

“Chapter I. Introduction” posted:

This is 1978-79. The first option isn’t available yet. So, how well do Steve and Ray do at explaining what an RPG is?

”WHAT IS A FANTASY ROLE-PLAYING GAME?” posted:

A role-playing game is a game of character development, simulating the process of personal development commonly called “life.” The player acts a role in a fantasy environment, just as he might act a role as a character in a play. In fact, when played with just paper and pencil on the game board of the player’s imagination, it has been called “improvisational radio theatre.” If played with metal and plastic figurines, it becomes improvisational puppet theatre. However it is played, the primary purpose is to have fun.

As a note: the next few sections are going to be mostly quoted verbatim, because they’re what I'm going to be using as the basis of how I review the rest of the book. I’ll try to keep it to summaries after this point.

”WHAT IS THIS ROLE-PLAYING GAME ABOUT?” posted:

RuneQuest is a departure from most FRP (as they are abbreviated) games issued since the concept’s introduction in 1974. Unlike most others, this game is tied to a particular world, Glorantha, first glimpsed through Chaosium’s board-games White Bear and Red Moon and Nomad Gods. Those who have not seen this world before will find part of it within these pages.

However, this game is not limited to Glorantha. The experience system, the combat system, most of the magic system, and the training/guilds system, and everything but the specific references to the world of Glorantha can be adjusted to fit any time and space with a minimum of hassle. We think you will find this system more realistic, and at the same time more playable, than any system you have seen before.

Wait, what did that last sentence say?

quote:

We think you will find this system more realistic, and at the same time more playable, than any system you have seen before.

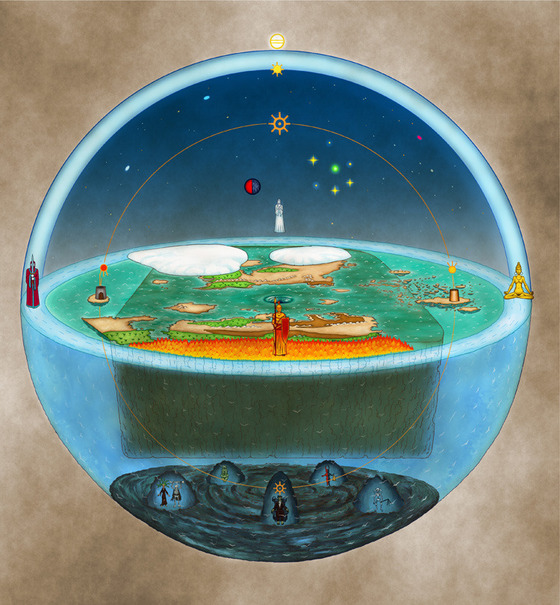

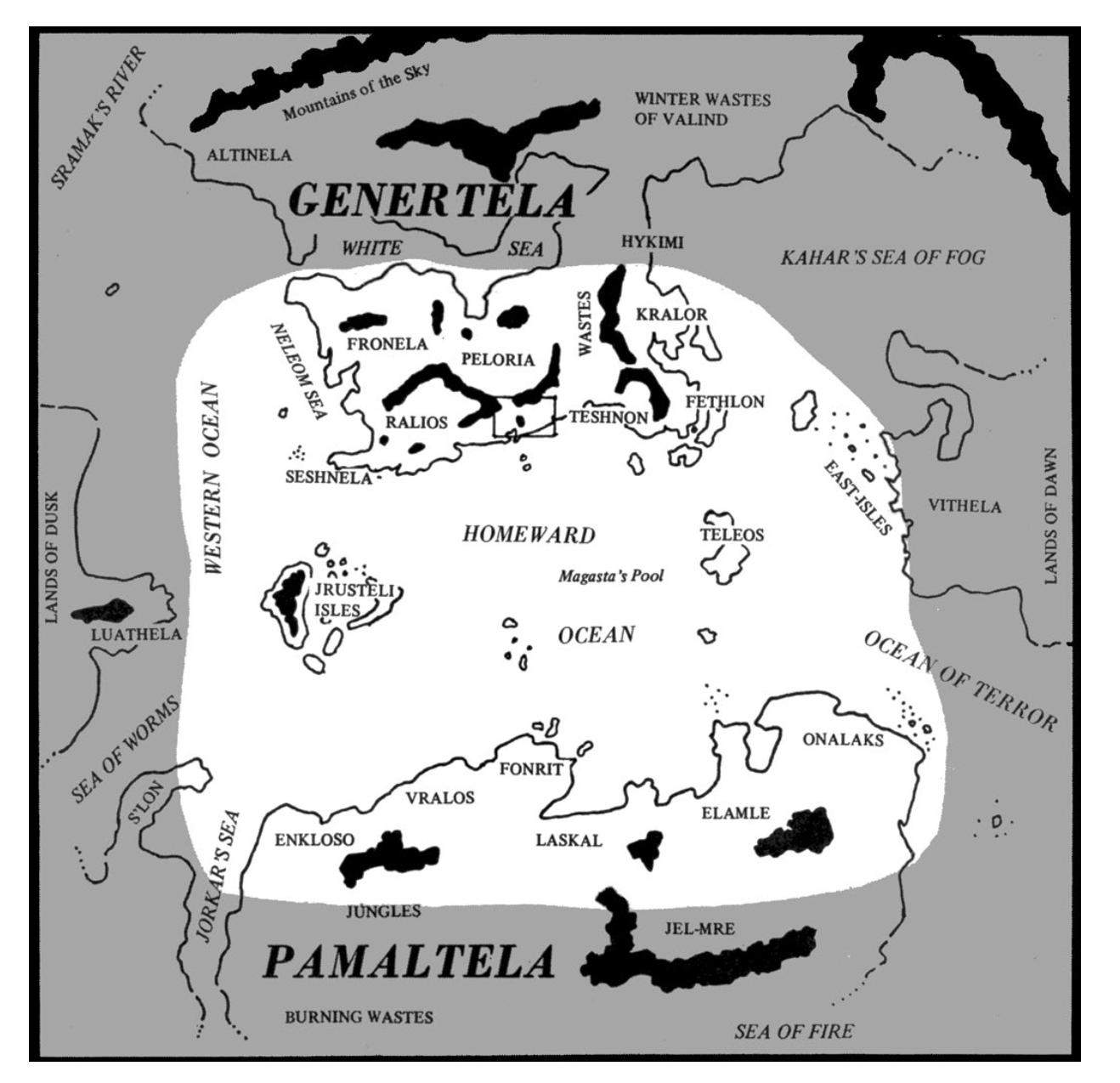

Above: the world of Glorantha, which is the default setting of RuneQuest 2E: a system more realistic and at the same time more playable than any system you have seen before. This image of Glorantha is not allegorical.

Moving on!

”HOW TO USE THESE RULES” posted:

Read these rules very carefully. Read all the way through once. Then roll up a character and see how the rules apply to that character. Get together with some friends and map out some beginning scenarios, with no surprises to any one until you are sure of how the rules work. Then, your imagination is your only limit.

”HOW TO USE THESE RULES, ctd.” posted:

We have tried to make these rules easily understood by anyone interested in the concept, not just experienced gamers. If you are an experienced FRP gamer, take those portions you can use and ignore the rest. Like any FRP system, these can only be guidelines. Use them as you will.

Then again, I may be looking at this from a completely different perspective– back in ‘78, AD&D was treading the new and dangerous road of “maybe everyone who’s playing Dungeons and Dragons should be playing the same game, rather than a chimerical mess of house rules connected sometimes only by a lineage of Xeroxes that got more blurry the further you were from Lake Geneva, WI?” Importing or mixing rule sets was just as common as it was today, and unlike Gygax, the RuneQuest authors seem to admit that RPGs are very much a medium where user and author contributions become extremely blurred.

Which is a great segue into this!

”FURTHER RULES” posted:

There are some questions left unanswered in these rules. We have attempted to provide a unified game system which can be played as is. Further supplements will ice the cake and expand on both how the game fits into the world of Glorantha, and how it can be expanded into other worlds.

We are interested in input from those who play this game. Players who devise cults, new spells, and new monsters are urged to write them up in terms similar to those found herein and send them to us. You will receive full credit for your creations and, of course, a copy of the supplement the contribution appears in.

Have fun.

But ok, how do we play RuneQuest 2E, really ?

”PURPOSE OF THE GAME” posted:

The title of the game, RuneQuest, describes its goal. The player creates one or more characters, known as Adventurers, and plays them in various scenarios designed by a Referee. The Adventurer has the use of combat, magic, and other skills, and treasure. The Referee has the use of assorted monsters, traps, and his own wicked imagination to keep the Adventurer from his goal within the rules of the game. A surviving Adventurer gains experience in fighting, magic, and other skills, as well as money to purchase further training.

The Adventurer progresses in this way until he is so proficient that he comes to the attention of the High Priests, sages, and gods. At this point he has the option to join a Rune cult. Joining such a cult gives him many advantages, not the least of which is aid from the god of the cult.

Acquiring a Rune by joining such a cult is the goal of the game, for only in gathering a Rune may a character take the next step, up into the ranks of Hero, and perhaps Superhero.

Speaking of which, most of you are wondering “What is a Rune and how do I Quest for it?” Well, I guess it’s time to actually look at the setting of Glorantha, which thankfully gets described starting on page 4.

… Wait, did I just spend all that time on one page?

Next Time: A Brief History of Time, or

* Technically 3E and 3.5E pushed a defanged Greyhawk as the assumed setting, and 4E had the "Points of Light" not-a-setting setting, but 5E was the first to overtly say that "the Forgotten Realms is the default setting, eat it nerds."

A Brief History of God-Time

Original SA post

Seriously WTF even is a RuneQuest

A Brief History of God-Time

Talking about the setting of Glorantha on a grand historical level is tough, because the creation of Time was just 1600-odd years ago. The Elder Races like the trolls and dragonnewts have demigods living and acting in the world who are older than Time itself.

Gods don’t live within Time, though. In fact, the creation of Time was a part of the Cosmic Compromise, which helped to re-stitch the world back together after Chaos, the anti-reality that exists outside of Glorantha, almost destroyed everything that ever existed. The Gods that survived (or were later resurrected) agreed to separate themselves from the world of mortals, and now exist in the God Time (or Godsworld, Or God Plane). The God Time exists separately from the mortal world, and is both the “time” before Year 1 and occurring right now– an infinite, repeating mash of myths and legends. If you’re familiar with the concept of the Dreamtime from Aboriginal Mythology, the God Time is pretty much the same concept. I assume that Greg Stafford, the creator of the world of Glorantha and an anthropology major, was basing it off of Aboriginal Australian cosmology, but it may be based off of another indigenous society.

From my personal perspective the God Time leaves some interesting setting implications for the players that other fantasy worlds don’t have. In many FRPGs, gods are a tricky subject to deal with. In some settings, active gods begin to overshadow the actions of mortals within the world (Forgotten Realms is a culprit of this). Other settings make gods dependent on worship to survive. Settings can also make the actions, motives, or even existence/divinity of the gods an unknown aspect, like in much of the Sword and Sorcery genre. Since Glorantha is a Mythic Bronze Age Fantasy world, interacting with the gods is an expected part of the genre. Sticking the gods on the timeless God Plane and forcing them to act through their worshippers gives back the spotlight and agency to the Mortal World and the PCs while still making them godlike without the need for worship.

The division between the God Time and the Mortal World isn’t entirely cut and dry, though. Mortals can visit the God Time through Heroquests, which can either result in them gaining exceptional magic power and wisdom, or strand them in the middle of Too Many Cooks until they get their soul incinerated or worse by gods or monsters. A God can technically exist in Time, but that violates the Great Compromise, which may cause other Gods to break out the Nuclear Option and also enter Time to stop them (which is allowed in the Compromise). What’s worse is that anything that happens to a God inside Time happens for good, sometimes permanently. Ask the Trolls to find out how bad that can be.

Of course, this is also all false*, all true, and happening right now. And I’m getting ahead of myself. I didn’t even go over how the world was created and why God Time and Time are separate.

Why The Gods Can’t Have Nice Things

Before even before time, there was Chaos, a roiling mass of impossibility and anti-reality. At some point, the Cosmic Court, who created the world out of the elements, appeared. There are

In the center of the great block of earth was a giant World-Mountain known as the Spike. It was the very embodiment of the orderly law that created the cosmos. The Sun God, Yelm, was acknowledged as the universal Bright Emperor and with the Cosmic Court ruled over Glorantha.

Then everything was perfect forever until Umath, the primal god of Storm and Wind, showed up and wanted a place in the cosmos. But there was no place left, so he tore himself out a spot between the Sky and the Earth. Yelm got mighty pissed and his courtiers killed Umath, but his children survived and the cosmos remained damaged. This is why the Storm/Wind element

One of these sons was Orlanth, who both wanted vengeance and his own place in the universe. He joined up with other outcast younger gods over the course of many legends, and eventually challenged Yelm, the Bad Emperor, for his birthright. While he lost every contest, in the final trial he showed the strange power of the weapon called Death that he stole from his brother, and sent Yelm and his court screaming into hell.

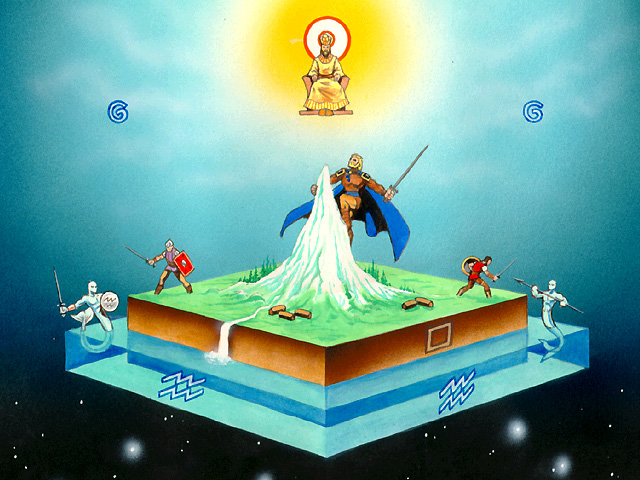

Allegorical image of Orlanth challenging Yelm in the God Time. From the King of Dragon Pass video game.

After this point everything started to go bad. The end of the

It was around this point (God Time, remember) Orlanth realized that he had made a huge mistake and needed to resurrect Yelm to save the universe. He decided to travel to the Underworld in search of Yelm and to make things right. Six other people came with him, and the Seven Lightbringers set out on their long quest.

The Lightbringers crossing the sea during the Great Darkness. From the King of Dragon Pass video game.

After many trials, they finally reached Yelm in the court of the dead, surrounded by all the other gods who had died. After surviving their trials and punishments, Orlanth and Yelm came to an agreement: Orlanth promised to let the future be like the past, which included all pasts (God Time, remember). Yelm admitted that Orlanth and the other gods and mortals without a place in the old order had a right to exist. Yelm would become the Bright Emperor again, and Orlanth would be the High King of the gods at the same time (again, God Time). The final act, an unnecessary extension of friendship by Orlanth, caused the enigmatic goddess Arachne Solara to appear and lay out the great Cosmic Compromise that would repair the world, which all the Gods agreed to. As part of the Compromise, all things that had died before would be allowed to live again for half of the time: this is why Yelm rises and sets each day, and why Ernalda becomes dead and cold for half the year.

Just as the Compromise was finished, the hordes of Chaos entered the underworld. The gods, now finally united against Chaos, wrapped them in a great made by Arachne Solara and defeated them all. The web was then cast across the universe, trapping all of Glorantha within time. As Yelm rose into the air, the first day of Time began. The God Time and the Mortal World were separated forever.

later bitches im outa here

Of course, this is also all false, all true, and happening right now. And to be honest, everything above is just a summary of what the Orlanthi, the cultures who worship Orlanth’s pantheon, know happened. If you ask a Peloran, a shitty wizard, or an Elder Race creature you will get a very different story of why time exists, though many aspects like the Great Darkness will remain the same. Such is the nature of the God Time.

In the text of RuneQuest 2E, this story is very, very briefly covered in Chapter I before going into the actual setting history. However, I wanted to cover a more detailed form of the “Monomyth” as it’s sometimes called because it’s such an integral part of the setting. As we’ll later see, aspects of the struggle between Orlanth and Yelm are echoed or alluded to by the various mortal conflicts that happen inside history. And the greatest mortal conflict, the Hero Wars, is about to start between a bunch of backwater Orlanth-worshippers and a Lunar Empire whose heartland is where the Yelm-worshippers live.**

My Uncredentialed Take on All This

As mentioned previously Greg Stafford, the guy who came up with all this, is trained as an anthropologist. He is also an expert on mythology, and these two things combined is probably why Glorantha is able to have such detailed setting mythology while still allowing for cultural and religious diversity. God Time is weird and non-linear, and allows for multiple explanations for the same thing. There’s dozens of Sun Gods besides Yelm, and they’re all equally the Sun (though Yelm is more equal than others). Different groups of Orlanthi know different details to the same myths, or even contradictory myths, and they’re all true. Sure, you can “prove” one myth to be truer than another using a Heroquest, or discover new myths, but the God Time is ultimately subjective yet sacred and eternal.

And that’s the thing: Greg Stafford has said that a lot of Glorantha as a setting is based around the “interaction of the Sacred and Profane” in the sense of the human relation to religion. In RuneQuest 2E much of the magic system, as we’ll see, is all about this interaction between far-off gods and their devotees. The details of legends and rituals are often held secret from foreigners because of their sacred nature, a real-world occurrence in a lot of modern indigenous and historical cultures that Greg is undoubtedly familiar with. And besides, religion is such a source of tangible power in Glorantha that keeping these things secret makes just as much sense to an Orlanthi or Peloran as keeping nuclear launch codes a secret does to us.

As a note: in future sections of the review, I probably won’t be referring to any Glorantha setting material that’s outside of RuneQuest 2E’s core, because there’s a shitload of it and I’m not exactly an expert on what is or isn’t canon anymore. I don’t know how interesting all this tedious analysis is, so feel free to tell me to speed up. And if I got anything wrong on the setting info, please let me know. This was mostly off of memory.

Next Time: Actual Mortal History That Follows Causality

* The Shamanistic societies of the world know that the gods are really just extremely powerful spirits, not uniquely divine. Likewise, the Atheists of the west know that the Gods are just runic emanations that have lost the wisdom to acknowledge the truth of the Invisible God as revealed by Malkion, PBUH. But in RuneQuest 2E’s default region of Dragon Pass, the God Time and the story I just told is what most people know to be true.

** There are other Hero Wars which will occur at the same time, but this one is the war that will occur in RuneQuest 2E’s assumed setting region of Dragon Pass.

History: or, The Rest of Chapter I

Original SA post

Questing for Runes may be hazardous to your health. Please ask your doctor before considering Runequest.

History: or, The Rest of Chapter I

So far we’ve been making seemingly negative progress trying to summarize the history and cosmology of RuneQuest 2E ’s base setting of Glorantha. This will hopefully be the last update where we’ll be immersed in setting information, so after this point we can finally look at this system that’s apparently more realistic and at the same time more playable than any system we’ve seen before.

So, let’s go over what RuneQuest 2E has to say about human history in Genertela .

The First Age: I am Gbaji and So Can You

For the first couple of hundred years humans and the other mortal races spent their time trying to adjust to living within time, and developed new ways to contact their gods. A group of mortals and demigods in Dragon Pass created the First Council, which was kind of like a Bronze Age League of Nations. Much like the LoN, it was kind of poorly conceived and fell apart due to past grudges between the races, and the remainder got some bad ideas in their heads.

quote:

Inside dissension and outside enemies forced the formation of the Second Council, a warlike empire, which grew in arrogance and power until they dreamed of bringing back the God Time. The experiment ended in the birth of Gbaji, the Chaos god, whose reign of terror kept Glorantha at war with itself for 75 years. This was the death knell of the inhuman races, which have never had the same stature in the world since then. This was the end of the Dawn Ages.

So yeah, this bit of the setting remains pretty close to the modern version of the tale AFAICT. It doesn’t talk about Arkat or Nysalor, the two demigods who defined the Gbaji era (and either one or the other or both is considered Gbaji by surviving cultures), but it’s enough to get by. Good on Steve and Ray to keep the details short. I think it’s interesting that the in-setting reason for the dominance of humans over the otherwise superior trolls, dragonnewts, elves, and dwarfs is due to an utterly fucked-up supernatural war, rather than vague handwaves about it being the “age of Man” or whatever.

tl;dr.

The Second Age: Fuck You Dad I’m a Dragon

”Vague Hanging Sentence #1” posted:

Out of this shattered world grew new political entities.

After some time existing as a smoking crater, Dragon Pass was repopulated by The Empire of Wyrms Friends, a mixed human-dragonnewt society that “Delved deep into spiritual byways.” Later fluff would clarify that this was basically a magical pyramid scheme with dragons.

quote:

After several hundred years the empire was replaced by a ruling body of men and gods called the Third Council. Legends relate that there was no telling the men from the gods in the council chambers.

But the magic of the council could not counter the miseries of its worshippers, or control the swords of the rebels who did not sacrifice to them. Foreign gods gained power and prestige as the provinces of the Third Council revolted or were overrun by invaders.

At last the council turned its energies to defending its worshippers. Epic battles raged across the land. Finally, the dragonewts, dormant for centuries, rose against the council and slew them all.

Wait, so when did they stop being the EWF? Was it gradual? Well, it doesn’t matter now, since the human allies of those dragonnewts will turn on them and begin genociding them. Unfortunately, as the name implies dragonnewts are related to the True Dragons, and so it’s not exactly a surprise that the True Dragons wake up and kill every human in Dragon Pass in retaliation.

quote:

The dragons from all across Time and Space assembled in their ancestral home to preserve the purity of their birthplace. The Dragonkill War got its name from what the dragons did, not what they suffered. Humans have feared the dragons since that time...

Dragons are not exactly a fire-breathing lizard in Glorantha. The answer to “where is a dragon’s lair?” is “don’t you mean, when?” From the King of Dragon Pass video game.

OK, so Dragons aren’t exactly just giant magical lizards but are magical entities that don’t follow the laws of Time. It probably was a bad idea to pick a fight with them/exist in their general direction!

quote:

Elsewhere, old empires shook and seas were utterly closed to human crossing.

Must be one of those other “new political entities” I heard so much about. Well, it doesn’t matter, they’re all dead now.

The Third Age: Fuck You, Moon God dess

quote:

North of Dragon Pass, in the region called Peloria, there arose the Red Moon Goddess. In her were balanced Constancy and Change, Life and Death, Love and Indifference, and all the dichotomies of the Universe, including a touch of Chaos. Her arrival changed the face of the land.

After living in Glorantha a short time she ascended to the heavens where she remains in her cyclical beauty, viewing the land which she left to her family below. The ever-reincarnating Red Emperor of the Lunar Empire is her son and her pride.

So yeah, up until now there was no moon in Glorantha, and Her ascension into godhood (and out of Time) left behind a militaristic empire utterly devoted to her as well as a giant red/black orb in the sky. The Lunar Empire has rapidly expanded until it met physical and magical borders everywhere except to its south, where it can finally gain access to the sea.

At this point you’re probably thinking rightly that Dragon Pass is fucking cursed. Unfortunately, enough generations have passed that some idiots decided to repopulate the area. See the video game King of Dragon Pass for a semi-accurate retelling of the founding of the Kingdom of Sartar.

A few generations later, the Lunars conquer dragon pass utterly, making all your work in KoDP pointless.

quote:

But the spirits of Sartar Temple incited the natives to rebellion. When the Lunar Priestesses attempted to construct a Temple of the Reaching Moon on Wind Top to extend the Glowline, a dragon unearthed itself under the foundation, devouring the priestess there and half of the attendant armies. Shortly afterward, rebellion in the outpost city of Pavis spelled Lunar defeat, and the victorious barbarian warlord led his army towards Dragon Pass.

The warlord was Argrath Dragontooth, member of a minor Sartar household and refugee from Lunar justice. He had grown famous amongst the tribes of Prax and now claimed heirdom to Sartar’s realm. He defeated Lunar forces in a military victory and relit the fire in Sartar’s Temple with a command. Thus, the empire was thrown back again.

OK, so not so pointless. So why should I even care about all this?

quote:

The bravery and glory of Sartar’s fight for independence attracted thousands of volunteers, and people from all about Glorantha became Adventurers in order to build up their skills to take their places in the ranks. The period was known as the Hero Wars, and the fighting around Dragon Pass drew the greatest collection of Heroes and Superheroes the world had ever seen in one place.

This is the game of that period. In these pages one learns how to start to become a Hero, to take one’s place in the Hero Wars.

So, we get back to the goal of the game: not only are the players trying to gain enough power to own a Rune, but they’re also trying to win the audition to have a starring role in Ragnarok. Based on all this, RuneQuest ’s game seems to be intended for a focus around personal combat, as opposed to dungeon crawling or a more generic system.

Suddenly, a Treatise on Socioeconomics

”TECHNOLOGICAL BASE” posted:

Glorantha is a Bronze Age world. This general statement is meant to illustrate the social development and cultural level of most of the people of the world.

Oh, ok, so since Glorantha is a Bronze Age society and this game seems to focus on being more realistic and at the same time more playable than any system we’ve seen before, I’d assume that the tin and copper trade networks are imp-

quote:

Bronze is common, and can be mined directly from the bones of the gods who died in the Gods War. These bones provide a ready source of the metal. Bronze is used throughout the rules to refer to the terrestrial metal to which it is most similar, but it also has some properties which are dissimilar from our earthly metal.

Well, this is where the whole “this is a fantasy setting” concept rears its head again. Glorantha isn’t afraid to betray our expectations that things work like they do in reality, and goes on to talk about how different “pure” metals like iron effectively act as anti-magic unless you’re attuned to that metal.

”SOCIOLOGICAL BASE” posted:

Glorantha is an ancient period and early Dark Ages world. It has far more to do with Mesopotamia, ancient China, Hyboria, and Lankhmar than it does with medieval Europe, Le Mort D’Arthur, or the Carolingian Cycle. Its heroes are Conans, Grey Mousers, and Rustums, not Lancelots, Percivals, and Rolands.

I suppose it’s good for RuneQuest to come out at the beginning and explicitly state that this isn’t a Medieval fantasy game. That being said, I think that overall D&D still takes infinitely more from “Hyboria and Lhankmar” (i.e. Howard and Fritz Lieber’s pulp fantasy) than it does the Chivalric Romance genre. (One of Greg Stafford’s other major works, Pendragon , is an actual RPG in that genre.) It’s a bit weird to have low fantasy stuff like Conan given as an appropriate character model alongside mythical culture-heroes like Rustum, though: they’re very different power levels.

Here’s a picture of a medieval fantasy elf, from the exact page they talk about “this is a Bronze Age game”

Steve and Ray go on to explain that in RuneQuest there isn’t an alignment system “unlike the worlds in other role-playing games.” Allegiances in RuneQuest are based more on politics, piety, and heritage than on nebulous ethical concepts, and lots of people are also only loyal to themselves. Seeing that Alignment is written in incredibly vague terms in the AD&D player’s handbook about what it means, It’s an understandable assumption that the writers of RuneQuest assume that it is some sort of cosmic allegiance. It also goes to show that “no alignment system” hasn’t been a unique RPG feature for almost 40 years. Not that the writers of fantasy heartbreakers would know about that. The text then goes on to explain that while the gods through their followers do play a major role in the world, they don’t normally oppose each other unless they’re “gods of Power... and only then within their spheres of interest.” No further explanation is given and it’s a bit unclear what that means.

An entire section of the book is given to explaining the monetary system of the Dragon Pass area, which is interesting for two reasons: first, it’s considered important enough to get almost half a page, and second, it shows how little is different between the preconceptions of D&D and RuneQuest 2E . You’ve got a weird non-decimal coin exchange system that goes Gold>Silver>Copper, with multiple different in-setting names for the coins. For whatever reason, silver, not gold, is considered the primary coinage for player use, and we learn the incredibly important knowledge that “one Lunar (silver coin)... is worth about one pre-WWII English pound, or 5 US dollars.” You know, just in case you’re from 1939 and get sucked through a magic wardrobe to Glorantha.

Ignoring that there really wasn’t an organized, let alone international system of metallic currency in Bronze Age Europe/Mesopotamia, this whole section implies that the same kind of treasure-seeking and money-changing is as important to RuneQuest 2E as it is for AD&D , seeing that it’s in Chapter I. I’m also reminded of how each Exalted edition’s core book spends a pointless amount of time talking about the various currency systems and denominations used in what is ostensibly a game about insanely powerful demigods.

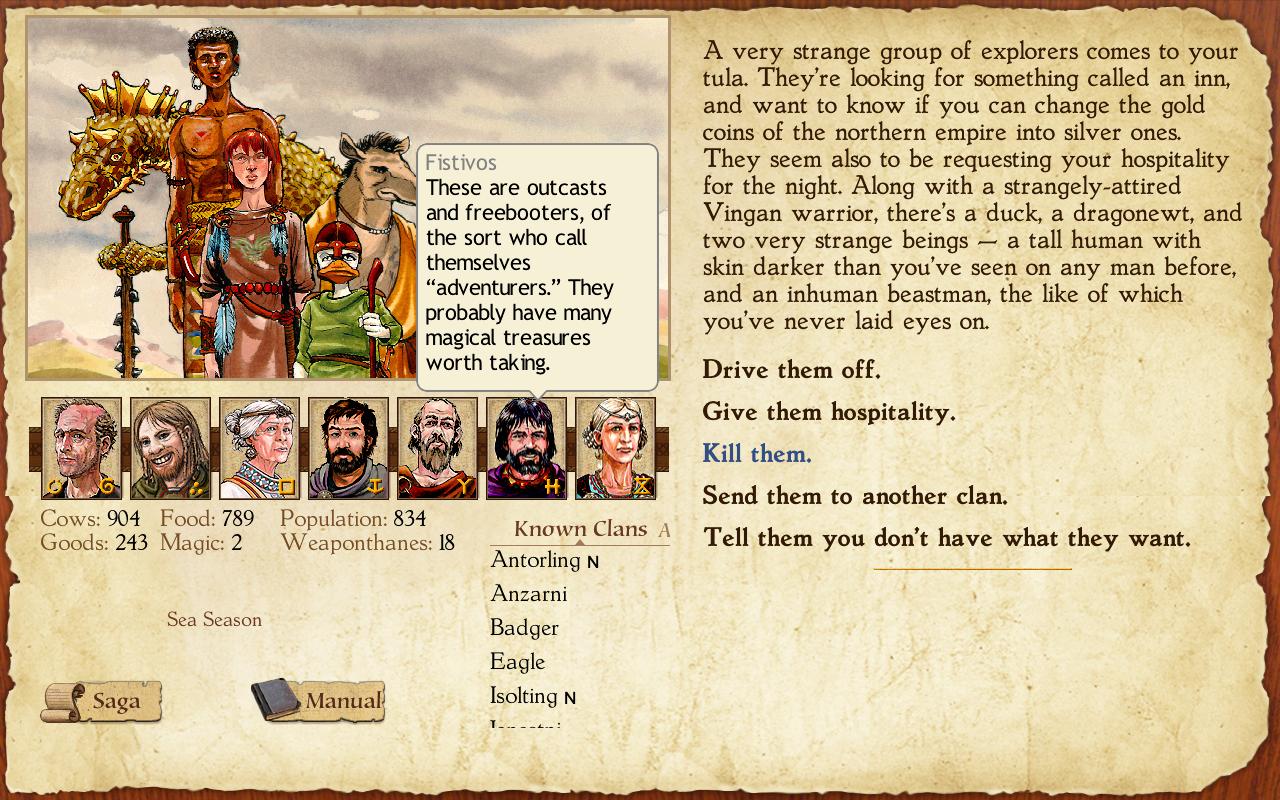

Fistivos is right, tbh. A random event that’s a jab at Player Characters in RuneQuest from the King of Dragon Pass video game.

I Can Show You The World

Anyways, I went over the basic cosmology of Glorantha in the last review part (Earth cube floating on Water, above Darkness, below Sky and Storm), but now we finally get to see the actual map.

A map of Glorantha, ca. 1978 AD. The Black rectangle is the Dragon Pass / Prax region.

Most of the Earth Cube is submerged below water, but some continents exist above the surface. The unshaded regions are where the Mortal races live, while the outer areas are the realms of demigods and primal elemental forces. A giant Cosmic river circles around the cube of earth as well. The northern continent Genertela is mostly temperate, and the southern contintent Pamaltela is mostly tropical. Most of the interesting stuff occurs in Genertela. The boxed region includes Dragon Pass, and you can see that it’s a major crossroad for Glorantha (hence why the Lunars want it).

quote:

Even in the central areas only some regions have been well- documented and mapped; others live on in the ignorance and bliss of illiteracy. Further publications by The Chaosium will explore and explain some of these regions in more detail. Interested parties are urged to contact The Chaosium for the details.

Oh, you have no idea.

A brief summary of Genertela.

Chapter I concludes with a timeline of Dragon Pass in the 3rd Age, that includes a lot of tantalizing, out of context stuff. Notable passages include:

”1380” posted:

War between hill peoples of Dragon Pass and Ducks.

”1387” posted:

Yara Aranis is born, a demonic barbarian-killing daughter of the Red Emperor. The barbarians no longer grow in strength.

”1550” posted:

Dragonewts Dream begins, lasting for five years. No human has an idea of what this was about.

”1616” posted:

God-King of the Holy Country disappears and the Masters of Luck and Death fail to bring forth a new incarnation.

And with that, we’ve finally finished Chapter I. Next time we’ll be diving directly into the Character Creation process, since this is 1978 and the concept of explaining the base rules of the game before any other content hasn’t been figured out yet.

Next Time: Imagine Rolling 3d6 Seven Times in Order on The Edge of a Cliff. RuneQuest 2E Works the Same Way

Character Creation

Original SA post

In terms of Illusory Time, this part of the review is not late.

Chapter II: Character Creation

So we’re now finally going to the character creation chapter, where we’ll learn how to create a character who can quest for Runes and maybe help to destroy the world in the Hero Wars.

”CHARACTERISTICS” posted:

To create a human Adventurer, the player rolls 3D6 for each of the following characteristics. This provides a range of from 3 (low) to 18 (high) for each characteristic and this range gives the basic parameters of human development.

In terms of deviating from AD&D, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree for RuneQuest when it comes to the very basics of how a character is made. One major difference is that “roll 3d6 in order” is the default for RuneQuest , while for AD&D they spend an entire paragraph warning against this specific character generation method in the Dungeon Master’s Guide. That being said, it’s 1978 and the AD&D DMG hasn’t been published yet.

Interestingly enough, what dice you roll for each characteristic changes depending on what your character’s race is. The game assumes that you’re making a human character, but has all the needed rules for PC non-humans in the Monsters chapter. Skimming ahead, RuneQuest deviates from AD&D by statting out monsters based on the same basic rules as PCs (a full set of ability scores/characteristics), so the idea that “players and monsters should use the same design basis” is already present in game design.

Anyways, there are seven characteristics in RuneQuest 2E.

-

Strength/STR:

how strong a character is. This limits what weapons and armor they can wear, along with extra weapon damage.

-

Constitution/CON:

how healthy a character is. Determines their HP and also their resistance to poison or disease.

-

Size/SIZ:

how big a character is. This influences “his ability to do and absorb damage.” High SIZ makes it hard to hide or dodge attacks.

-

Intelligence/INT:

the character’s ability to learn and understand new skills and magic spells.

-

Power/POW:

the strength of a character’s soul and magical ability. POW allows for better magic, but they also caution that

having too high a power level makes it hard to hide.

That’s pretty rad.

-

Dexterity/DEX:

a character’s speed and coordination. Just like in

D&D

, this means more than just manual dexterity like it would anywhere else.

-

Charisma/CHA:

factors into gaining hirelings and accessing training, along with “various other uses.” Like in AD&D, this isn’t a measure of your beauty. We’ll see how useful CHA is later down the line, they promise.

Abilities: Basically Everything You Actually Do

”ABILITIES AND HOW CHARACTERISTICS INFLUENCE THEM” posted:

Each Adventurer has various abilities which he will be able to improve with training. His characteristics will influence how he does initially with each ability. The following list goes through each major category of abilities and demonstrates with a table how each class of ability is influenced by characteristics.

So, this is the part where we actually see how characteristics affect a PC’s ability to do things. “Abilities” is a catchall term in RuneQuest 2E for all the stuff like actions, passive defenses, HP, and basically every other aspect of a character that isn’t “magical.” As with all the “bend bars/lift gates” stuff in AD&D , modifiers to character abilities are based off of a table and can’t be figured out based on just looking at the characteristics you rolled.

However, unlike AD&D , the conversion from the characteristic number into a % modifier to that ability takes on the exact same format each time, save for HP and damage bonuses:

pre:

Characteristic Characteristic Roll

01-04 05-08 09-12 13-16 17-20 Each +4 After

Low-modifying Stat -5% +5% +5%

High-modifying Stat -10% -5% +5% +10% +5%

Each ability is modified by at least two different characteristics, and to prove that it’s the most realistic RPG out there, the authors have an explanation as to why for each ability. Of note is the fact that POW modifies just about every ability since it’s a measure of how well-attuned they are to the universe. POW is starting to look like it’s the God Stat of RQ2E both thematically and mechanically.

There are 9 character abilities covered in this chapter:

-

Attack:

how well you can hit an opponent. Attacks in

RQ2E

are meant to represent multiple feints and stabs rather than a single strike, much like in

AD&D

. Most of the text implies that the Attack ability is structured in mind of melee combat.

-

Parry:

your ability to deflect blows with a weapon or shield. I’m beginning to notice a definite assumption of melee combat in RQ2E’s rules.

-

Defense:

your ability to dodge attacks, which is a penalty to your opponent’s attack roll. “In modern Japan, they have turned it into the martial art of Aikido, but no one in the ancient world we game in has developed this as a discipline. All Defense is learned through experience.”

The text goes on to show how a character’s defense can increase by first 1) successfully dodging an attack

within the margin of error caused by your current defense score

and 2) succeed on a % roll under their INT score. I believe that this method is used later in

RQ2E

as well as in later Chaosium works like

Call of Cthulhu

. With multiple opponents, a character splits up their defense score between each opponent. Sounds like a bit of a bookkeeping headache.

The text goes on to show how a character’s defense can increase by first 1) successfully dodging an attack

within the margin of error caused by your current defense score

and 2) succeed on a % roll under their INT score. I believe that this method is used later in

RQ2E

as well as in later Chaosium works like

Call of Cthulhu

. With multiple opponents, a character splits up their defense score between each opponent. Sounds like a bit of a bookkeeping headache.

-

Hit Points:

how much you can get hit before dying. This isn’t a +/-% thing, but is instead just a flat bonus or penalty to max HP. Your base HP is equal to your CON score, and your SIZ and POW add a few extra to the score.

-

Damage Bonus:

this is the weird one: first, you average your STR and SIZ, and then you compare it to the table to see if you get an extra bonus die on your damage rolls.

-

Perception:

you ability to notice interesting or strange stuff.

-

Stealth:

your ability to hide and move silently. Unlike most other abilities, high POW and SIZ characteristics are a definite problem if you want to be the Grey Mouser or Garrett.

-

Manipulation:

your ability to work your fingers well. Pickpocketing and trap removal are directly invoked here, which shows how little removed the assumptions of

RQ2E

are from

AD&D

for what you’ll be doing.

-

Knowledge:

your book lernin’. All your academic skills are modified by this.

Improving Characteristics

So, in AD&D , it’s pretty hard to increase a character’s ability scores until they gain access to the wish spell. In RuneQuest 2E , there’s a whole bunch of ways to do so, most of which involve the mechanical concept of training. However, you can’t improve a score past max of dice rolled for characteristic + 3 , which is 21 for humans.

The catch though is that only a few of the characteristics (STR, DEX, and CON) can be improved by training, while INT, SIZ, and POW can’t be altered by mundane means. CHA is handled completely differently from the physical stats in terms of improvement, and is “changed by the success or failure of previous ventures which have a definite influence on the Adventurer’s current CHA.” So, basically up to campaign events and Referee fiat, with a few extra rule/suggestions thrown in. In addition, a character’s STR or CON can only be improved up to the levels of some of the related characteristics: CON can only go up to the value of the character’s STR or SIZ, whichever is higher, etc.

So how do you improve a stat? Training! Training is described in Chapter II in terms of the cost to pay the teacher (in silver coins) and the time needed on an hourly basis to increase the stat. The whole aspect of “training as advancement” is something that’s in a lot of games from this era, but I have to say that it really hasn’t aged well. In RuneQuest 2E it isn’t explained whether you’re supposed to handle training as just between-session bookkeeping, or are meant to be role-playing interactions with NPCs. Since the book describes the types of guilds that can offer this training, I’d assume it’s the latter, but who even knows. Hopefully this will be clarified later.

Starting Equipment: A Not-So Classless Game

Of course, this is a realistic fantasy RPG. We’re not finished creating a character until we get our starting gear and cash. So, what do PCs get and how does it vary?

It turns out that RuneQuest 2E determines your starting equipment and wealth based on your character’s social background, which is rolled on a table. I’m not sure how well this translates to humans in regions outside of Dragon Pass or Pavis, let alone for the Elder Races, but I suppose that simplicity is something we should be happy for at this point. Players first roll on a d100 table to get their character’s background (Peasant, Townsman, Barbarian, Poor Noble, Rich Noble, or Very Rich Noble) and then roll for their wealth based on that result. It’s not an even chance for each background, either– you have to roll 00 or (100) on a % roll to be a very rich noble, and Townsman, Barbarian, and Peasant are the most common backgrounds. Rich and Very Rich nobles even have a yearly income unlike the other backgrounds– they have an estate they can go to when they need cash.

In addition to your starting wealth, characters have a pre-defined set of starting items composed of some default stuff and then extra stuff based on your background. It should be noted that only Poor Nobles and above start with a weapon by default. If you want to fight, you need to buy a weapon first, prole. In conclusion, income inequality is a serious issue in the Lunar Empire that can only be addressed by breaking up the too-big-to-fail Temples of the Reaching Moon. Or, in all seriousness, this may be realistic but I don’t find it a very fair system for determining starting PC resources.

The Rurik Sidebars

Starting in Chapter II and continuing throughout the rest of the book are sidebars describing the creation and adventures of the hypothetical PC Rurik and his pals. These are actually pretty useful examples of play that are useful for anyone wanting to see character creation and other mechanics in play. I don’t have too much else to say about this, but the use of the expy Rurik to demonstrate various aspects of RQ2E was really helpful for me when reading this book.

What I Think of All This

By the end of Chapter II it becomes very clear how RuneQuest 2E is more than just a set of house rules for AD&D . Not only are there no classes, but the methods of advancement for PCs are intended to be based on in-game training and learning, rather than an abstracted XP system related to gaining money, killing monsters, or finishing adventures. RQ2E also uses a strong reliance on percentile rolls for basic actions, which are already grouped into seven major types because of the abilities. That being said, the importance and role of abilities aren’t exactly explained well within the rules, at least to a modern audience.

Interestingly enough, there are less decision points in character generation for RQ2E than in AD&D . Nearly everything except your character’s race is randomized during character creation in RuneQuest , and that really just determines what dice you roll for characteristics and what cults you can join later. Everything else is based on dice rolls until the session starts. In AD&D , the randomness is mostly frontloaded in the form of ability score rolls: the rest of character creation is based on choosing a race, then a class, then whatever starting gear they can afford. Character creation in RQ2E is pretty quick, but at the cost of player control over the process.

It’s also neat to note that unlike other systems or houserules of the time, there’s no gender-based penalties or limitations on what stats a PC can have (during character creation, at least). Coupled with the detailed Kyger Litor cult later on, RQ2E 's core book probably gets the award for “most feminist or gender egalitarian early RPG” by default.

Next Time: Reader Participation Point!

Do we:

A) move onto Chapter 3: Mechanics and Melee, or

B) don't wait until we finish reading the book, and create Goonalda of the Lowtaxanoli Tribe? (No other input needed, since she's already a default human and that's all you can choose in RQ2E )

Intermission: Creating Goonalda of the Lowtaxanoli Clan

Original SA post

No Runes were harmed in the making of this character.

In an unanimous landslide of one vote (thanks Josef Bugman ), we’re going to take a little detour to roll up a new player character and look at how they’re created in RuneQuest 2E .

Intermission: Creating Goonalda of the Lowtaxanoli Clan

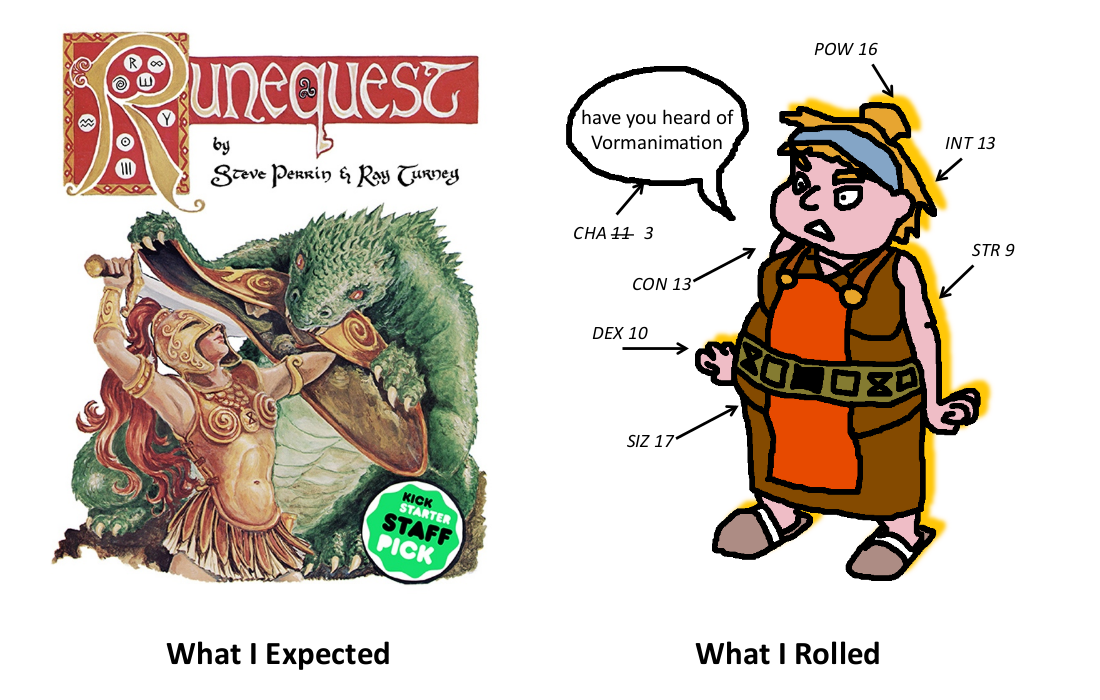

So, let’s see what the process is to make a character based on the steps outlined in Chapter II. As discussed previously, the only real point of decision that affects us mechanically is to choose our character’s fantasy race, and it’s implied that we should really, really just make a human character. So let’s do that, and roll 3d6 in order:

pre:

Name: Goonalda Race: Human Gender: Female Characteristics: STR 9 CON 13 SIZ 17 INT 13 POW 16 DEX 10 CHA 11

Weird Twitter references aside, we have two other things we have to roll before we’re done with Goonalda’s random pre-game rolls: background and starting wealth in Lunars (silver coins).

pre:

Background: d100 - 13 - Peasant Starting L: d100 - 86 L

RuneQuest is the ultimate in realistic magical giant women simulation games.

But jokes aside, this is actually a very good long-term character to roll up. While our starting STR is just above the bracket where we start to get penalties to tasks, our CON is high enough to be at least an above-average survivor in combat. Where Goonalda really starts to shine is that we rolled a 17 for her Size– which, if we go to the Monsters section of RQ2E’s core book puts her at the average size of a Dark Troll. Mechanically, this sticks Goonalda right into the largest possible bracket of SIZ modifiers for a starting human character, and more importantly means that her STR and CON can be increased through training up to this bracket.

While her INT can’t be increased naturally, Goonelda is smart enough to get into the characteristic bracket where ability bonuses start to show up. For how much advancement seems to be predicated on a high intelligence score, it is a bit dumb for it to be one of the “you can never ever change this normally” stats (let alone that each stat is so randomly rolled and that a single stat determines how fast a character learns stuff). Another gameplay issue left behind by the Chaos God of Realism, I suppose.

Goonalda’s POW is just below the cutoff point to get a bunch of minor bonuses for a lot of abilities, but we can’t increase it any further through training. Goonalda’s DEX and CHA can be increased to 21 (the human maximum) through training in the case of DEX, and through Referee fiat and events in the case of CHA. Her average DEX and CHA don’t give her any special modifiers to any abilities.

So, what about her abilities? Goonalda’s high SIZ is unfortunately a detriment in most cases, but her INT helps to cushion these effects for most abilities. Goonalda does get a bonus to her attack damage, but otherwise her stat adjustments are mostly minor.

pre:

Abilities: Ability Modifier Breakdown Attack: +5% +0% STR, +5% INT, +0% POW, +0% DEX Parry: -5% +0% STR, -5% SIZ, +0% POW, +0% DEX Defense: +0% -5% SIZ, +5% INT, +0% POW, +0% DEX HP: 15 13 (CON score) + 2 (SIZ modifier) Dmg Bonus: +1d4 Avg. of STR + SIZ is 13 (+1d4 dmg) Perception: +5% +5% INT, +0% POW Stealth: -5% -10% SIZ, +5% INT, -0% POW, +0% DEX Manipulation: +5% +0% STR, +5% INT, +0% POW, +0% DEX Knowledge: +5% +5% INT, +0% POW

Overall, Goonalda has an above-average set of stats with no major weaknesses, but needs some physical stat increases to really start to excel. Since we’ve only covered up to Chapter II, that’s all we can do with Goonalda for now. Once we get done with the other chapters dedicated to combat, magic, and noncombat skills we’ll probably revisit her and see exactly what a 16 POW will look like. For now, here’s her character sheet.

pre:

Name: Goonalda Race: Human Gender: Female Culture: Theyalan / Orlanthi (Sartarite) Clan: Lowtaxaroli Characteristics: STR 9 CON 13 SIZ 17 INT 13 POW 16 DEX 10 CHA 11 Background: Peasant Starting Money: 86 L Abilities: Attack: +5% Parry: +0% Defense: +0% HP: 15 Dmg Bonus: +1d4 Perception: +5% Stealth: -5% Manipulation: +5% Knowledge: +5% Possible Characteristic Advancements: STR: up to 17 (SIZ score) CON: up to 17 (SIZ score) POW: Magical advancement up to 21 (Racial Maximum) DEX: up to 21 (Racial Maximum) CHA: Referee Fiat up to 21 (Racial Maximum) Equipment: Clothing Fire-making gear Snares Drinking skin Basic camp gear Torches

Next Time: Mechanics and Melee

The Sections on Adventuring in RPGs That Everyone Doesn’t Look At Despite Them Being Important for Running the Game as Intended

Original SA post

This review part was brought to you by the Stasis and Undeath runes.

Mechanics and Melee

Chapter III of RuneQuest 2E covers a somewhat confusing group of topics: for whatever reason, the authors decided to group together more general rules about adventuring time and movement with RQ2E’s melee combat system. From a modern perspective, I suppose that grouping the subject matter like this was an attempt to describe what we’d now call the “action economy” of the game in one concise location, though it does still feel somewhat disjointed. (Spoilers: I just finished reading it and it is just as disjointed as I thought at the beginning).

The Sections on Adventuring in RPGs That Everyone Doesn’t Look At Despite Them Being Important for Running the Game as Intended

There are three common rule concepts in old-school fantasy games that everyone likes to ignore: time measurement, travel movement, and encumbrance. Usually this is because these either don't seem actually critical to running the game, or the rules as written require such a tedious amount of bookkeeping regarding all three that it's just excised by a group of players to save the parts of the game they enjoy. However, this does cause players to ignore the design precept where for these games (sometimes intentionally on the part of the designer), time and space within the game world are meant to be finite resources that had to be tracked. Removing these rulesets does change how the game plays, even if they're seemingly secondary to other rules. RQ2E covers how all three of these work, regardless of if anyone uses them, in just one half of a chapter.

RQ2E uses three different forms of time measurement within the game rules: the Game Week, the Full Turn, and the Melee Round. Much like in AD&D, turns and rounds are not arbitrary lengths of time that determines what a character can do, but is meant to represent actual measurements of time– a melee round lasts for 12 seconds, and a full turn is 5 minutes (25 melee rounds) long. While the melee round’s purpose in tracking game time is self-explanatory, the full turn “is used to denote passage of time during a scenario.” I know that for AD&D, the DM is supposed to keep track of the passage of time down to an exact value, since time and resource consumption is meant to be a major challenge in classic dungeon crawling. But I don’t really get why RQ2E also tries to give such fastidious time management rules. I suppose it’s probably a mix of tracking long-term conditions and magical spells, and then it being part of the RPG design zeitgeist from the time.

The last length of time, the Game Week, is meant to represent a period of a week within the game:

”GAME WEEK” posted:

This describes the passage of time for the characters in the world of Glorantha. Training, Rune Magic, and other considerations are based on the game week.

How long is a game week in real time? A time scale of one real week per game week makes the game drag unless one is running a campaign by mail. The authors recommend a scale of one real day equals one game week. Simplified bookkeeping lets players keep characters in play fairly continually. Adjust this to fit the type of campaign being played.

Wait, so do Steve and Ray suggest that one play session is one game week, or that one actual day is one game week? In either case, it’s interesting that this time length can be controlled to scale the frequency of long-term character advancement and the passage time passage. Since what we’ve seen of character advancement relies on a system of training, you can really only improve yourself once an adventure ends and time passes within the game. So, RAW the game can limit a PC’s access to advancement both through time (game weeks) and space (finding an actual trainer nearby)

And speaking of that, the next section covers movement on both the macro- and micro-scale for characters. The usual RPG staple of daily travel rates and the terrain modifiers that can alter them show up here, with a bit of complexity thrown in to explain how they act cumulatively. “Scenario Movement” is a description of how far a character can move in a full turn. Surprisingly enough, there are no modifiers based on character race or SIZ, or really anything, besides the rule that riding animals can run twice as far.

When we get to the rules on Melee Movement we start to see the granularity we’d expect from the most realistic and at the same time most playable RPG of the 1970s: creatures have something called a movement class, rated from 1 to 12, which determines the amount of movement units you get in a melee round. A movement unit in RQ2E is “3 meters or 10 feet” in length. The distinction in difference between melee movement and scenario movement is explained by noting that people generally move more slowly when other people are trying to kill them. All in all, it’s a pretty barebones system that does a good job making a quantitative movement system to use for melee combat.

So, we now get to the most hated and ignored set of rules across all fantasy RPGs: player character encumbrance. It’s been an issue for such a long time that even the authors here admit that most of them are trash. Surprisingly enough, RQ2E has a fairly loose system: you’ve got a max encumbrance equal to avg of STR and CON, a “Thing” is a generic unit of measure for random stuff equal to one point of encumbrance, and all items listed otherwise have a set encumbrance value. A character’s camping/adventure gear always weighs 2 encumbrance units, no matter what. The only real issue with this encumbrance system is that they then go and mess it all up by forcing you to sum up all coinage and jewelry you’re wearing to determine how much (if at all) your valuables add to encumbrance, and each type of coin or jewelry weighs a different amount. It’s a sudden drop into tedious bookkeeping that they managed to almost avoid, which makes it all the more jarring. Going over encumbrance gives a scaling penalty to defense and speed that increases with each point over encumbrance, rather than a fixed penalty.

Melee Combat

Melee rounds don’t follow an “I go, then you go” setup like in games that descend from AD&D. Instead, RQ2E has a combat round that is more similar to things I’ve seen in most wargames, where the round is divided into several action types which are then simultaneously resolved (movement-shooting-melee, for instance) rather than character-by-character. Interestingly enough, the first phase is just the players and referee saying what they want their characters to do during the battle– all real decisions by the players are supposed to happen at the top of a melee round. The four steps are:

- Statement of Intent: say what you’re going to do. “During the course of this melee round the intentions may be aborted… but not altered.” This means that you can cancel an action, but you can’t replace it with a new action.

- Movement of Non Engaged Characters: characters not in a fight spend movement units to move around. Like in some other pseudo action-point systems, characters that move half their total movement or less can do other things like attack or cast spells.

- Resolution of Melee / Missiles / Spells: Attacks are resolved in the order of something called “striking rank,” where the lowest value goes first. (I wonder if there’s any corellation between THAC0 and Strike Rank being ass-backwards from the modern POV.) If characters have the same rank, the highest dex goes first, and if DEX is the same, then the attacks are resolved simultaneously and damage is dealt last.

- Bookkeeping: I appreciate the honesty here.

Backing up a second, let’s go back to the attack resolution rules. Here we see the first real appearance of the d100 system used for the melee combat system of RQ2E.

”RESOLUTION OF MELEE” posted:

The attacker rolls D100 to see if he succeeded in attacking and a D20 for hit location (see end of this chapter). Remember to subtract the opponent’s Defense, if any, from the attacker’s chance of hitting. If the defender attempts to parry, he rolls D100 to see if he succeeded.

In the case of RQ2E, melee is an opposed roll with four possible end states composed of the interaction between attack success/failure vs. parry success/failure:

pre:

Atk Success | Atk Failure ________________|__________________ | Parry Success Weapon/shield | Attacker’s weapon of defender hit | takes damage ________________|__________________ | Parry Failure Attack actually | Ineffectual hits location | flailing

The book then takes an entire section to go into more detail on Strike Rank. SR gets modified by a character’s SIZ, their DEX, the length of the weapon, what attack type they’re using, and a whole bunch of other situational modifiers. Outside of melee, strike rank also acts as a more general action-point based economy, as up to 12 SR points worth of activities can be done in a turn. Which, explicitly in the rules, includes multiple magic and ranged attack types. Characters in melee can only attack, parry, defend, or attack with magic. At least in this case, RQ2E manages to avoid too much complexity when it comes to options in combat. I'm a bit leery of action point systems, but apparently only ranged characters can abuse the whole "multiple attacks a round" issue that pops up in these action economies. Melee combat again seems to be the main focus for Steve and Ray.

Hit Locations: Your HP Stat is Just a Helpful Suggestion Until You Die

RQ2E’s combat is generally known for having a hit-location system built into the combat rules. From a game standpoint, each character has two separate sets of values to keep track of when it comes to HP: their total HP, which is calculated using the rules from Chapter II, and their body part HP. Each part of the body has its own HP pool that is determined based on your total HP. Thankfully, they give a table to determine HP per location, and it isn’t just dividing your total HP over your body– otherwise, characters would be like tissue paper.

Whenever a character is hit, they take damage to whatever location was struck. If the total HP lost exceeds a character’s total HP, they die. If a body part loses all its location HP, then various nasty effects happen, often including “death within 2 turns unless healed.” Damage that exceeds the total amount of location HP on the location hit will be reduced to just twice the total amount of HP of that body part. If a character takes damage to a location that’s equal to 6+ max location HP, then either the body part is severed or they instantly die. Fun times in Mythic Bronze Age Fantasy!

Next Time: Combat Skills, or- Wait, Why Did They Divide Up The Rules Like This?

Combat Skills

Original SA postRand Brittain posted:

My second-biggest problem is that the people in charge of picking which books get written are a lot more interested in the Orlanthi than I am.

Same, I'm a fan of Ralios / Salfester and the new (non-medieval-European) portrayal of the whole "Western Canon" of Glorantha, for a lack of a better word.

And Fonrit

...But speaking of which, I still haven't figured out what a RuneQuest is. Can you make it? Can you eat it?

...

I’m not going to give up on this review until I find out what a rune even is.

Previous Review Sections

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: A Brief History of Godtime

Part 3: A Brief History of Time

Part 4: Chapter II, Character Creation

Intermission 1: Creating Goonalda of the Lowtaxanoli Tribe

Part 5: Chapter III, Mechanics and Melee

Chapter IV: Combat Skills

Now, looking back at Chapter III it becomes clear that we don’t actually have all the rules for both mechanics and melee combat. From our position at a time period nearly 40 years after it’s been written, most of us have been so exposed to percentile systems that we intuitively know how they work– but, one thing that we’ve also noticed is that our ability to hit things looks, well, kind of low. I mean, Goonalda has just a +5% melee skill to hit, and what even is that +5% added to?

So, in Chapter IV we actually get things explained to us. Attacks and parries work as a roll-under check where you compare a 1-100 roll to a character’s percentile value (modified, of course, by a billion things because this is the most realistic and playable system of 1978 AD). What actually determines your base chance to hit is something called a Basic Chance. If nothing else, you have a base chance of 5% (with modifiers added) to hit a thing with any random object you find). When you attack with actual weapons (or your punches/kicks/headbutts), this basic chance can be up to 25%, a much more reasonable value.

Special Damages

In RuneQuest 2E, characters deal critical hits whenever they roll within 5% of their total attack percent chance or if they roll a 1, whichever is higher. So, unlike in AD&D, the chance for a crit will increase over time with a character’s skill. Granted, you’ll need a 40% chance to hit before you start seeing any benefit from this, but it is an interesting divergence from the D&D mindset where crits are more due to luck than skill. Successful parries against crits will absolutely wreck the weapon used, and if there’s still damage to be dealt after breaking a weapon, it will still deal the remaining damage to the user.

Fumbles keep to a similar concept, where you’re much less likely to fuck up if you’re already an accomplished warrior, or are just using simple weapons. Rolling a 96-100 on a percentile die will make you fumble, and for every extra 20% of chance you have above 20%, the fumble range decreases, down to a minimum of rolling 100. While there’s a d100 Fumble Table, Steve and Ray recommend (based on their SCA experiences) that the Referee tailor it if it makes more sense. Most of the fumbles aren’t too sadistic, though there’s always the chance to critical hit yourself or an ally.

Impaling! RuneQuest is set in a setting based on the bronze age, so extra rules on what pointy things do when they get stuck is appropriate. Impaling works kind of like critical hits, but instead it triggers on the number that’s 20% less than your target value (so, for a 40% check, it becomes 8 or less). Impaling lets you roll for damage normally, and then adds the weapon’s highest possible damage. But it also causes your spear/sword/arrow to get stuck in a body or shield, so that’s a problem if you still want to use it. There’s a lot of optional rules dealing with the consequences of having a bronze speartip or arrowhead stuck in your body, but they follow the same attentions to details and love of fractions / percentile rolls we’ve seen so far. Of note though is that the roll for “pulling out an arrowhead” has one of the first defined skill checks that doesn’t directly involve killing people.

The book then goes on to note the bonuses to attacking surprised or prone characters and optional rules for critical parries and fumbles. Overall, this was critical information for combat rules, but I still don’t understand why Chapters III and IV were split up like they are. It may be that from a modern game design standpoint we’re used to a given set of rules being contained within one chapter, rather than a division of both training and combat into two chapters, where one’s for a grand overview and the other’s for complex rules. But in either case, I don’t think that the way that the book’s been set up so far is helpful for people new to RPGs in general.

Learning Fighting Skills: The Argrath Dragontooth Center for PCs Who Can’t Hit Good And Who Wanna Learn To Do Other Things Good Too

Like with everything else in RQ2E, character advancement is done through in-game training and experience. Most formal training is done through “guilds,” which is something that is never really talked about when I look at modern Glorantha setting material:

”Guild Credit” posted:

Bright, adventurous, men and women are at a premium in and around the Lunar Empire. The magical cults, fighting bands, and other guilds are all either (1) intermixed in the politics of the region or (2) trying to maintain enough power to keep themselves outside of same. To gain more members, the lesser skills of all are for sale, indiscriminately, often as much from the desires of the sponsoring deities as from political necessity.

By long tradition, the guilds, etc., must train those who come before them. There is nothing to say they must do it for free. However, beginning Adventurers do have the privilege of obtaining credit from the guilds.

Getting a guild to train you requires an amount of money based on the current value of the stat you’re trying to improve, which starts to brush up against the old conceit of “mechanics as game physics” while also being a way to curb rapid advancement in a level-less system. A high Charisma can reduce these training costs. Weapon training gets pretty complex in terms of how it works above a 25% score, and all sorts of caveats like “successfully attacking and parrying with the weapon on an adventure” limit a PC from just dumping all their money into becoming the Invincible Sword Princess past 50%. You also can’t get trained to more than 75% on any given weapon, and can’t increase a skill by more than 5% between adventures.

If you’re already at 75% skill with a weapon, or are in the 99% of Glorantha that doesn’t have enough civilization for a “guild,” you have to learn by experience. When a PC succeeds on an attack or parry, they make a note about it. At the end of the session, they roll a check against 100 – (specific Skill) + (Int modifiers). If this succeeds, they gain +5% to the skill, and can’t increase it again by experience until the next adventure. I understand that Call of Cthulhu uses a nearly identical method for character advancement, which figures because they’re both BRP systems.

At 50% skill a character starts to gain access to double-attacks in their turn. They can split up their skill value into any proportion they want and attack twice, parry twice, or both attack and parry in a given turn. Once a PC gets to 90% skill, they can even start to train other characters– I doubt that this ever becomes the main focus of a game, but it does allow the other party members to get free training. Weapons are also divided into 5 pretty broad groups. Having training in one weapon gives 1/2 of the training bonus to all other weapons in the group.

From what’s written in this book, it looks like the writers expect a given PC to gain in power based on both a mixture of training and experience, at least until they get to 75% in a given skill. This lets a PC increase a given skill by up to 10% between every adventure, which seems like a fairly good pace for character advancement.

As befits the era, Runequest 2E has complicated rules for grappling, weapon damage, and two-weapon fighting that are just sort of shoehorned onto the end of this section. But what confuses me is the setting implication that there are “guilds” which all work the same way and all accept the same methods of payment and give the same training. If “guild” is just a game term for groups that provide training in exchange for a standardized amount of money based on game balance, then it’s understandable. In this interpretation you could conceivably have a guild be abstracted as “that one guy in the village who’s good with a sword” and the 100 Silver for training be abstracted to “the favor he owes you for saving his two large sons from a Dragonsnail.” But within the book’s text, it’s never really made clear one way or the other and in many cases they make it sound like there really are guilds all over Glorantha that follow the sacred laws of Guild Credit. As someone who’s a fairly familiar with the setting from other sources, this is news to me.

Just What We Needed, More Ranged Combat Rules

Up until this point the vast majority of the rules covered for RQ2E were focused entirely on the finer points of melee combat. Like with any other fantasy RPG that goes into simulationist design, these additional rules for ranged attacks are mostly meant to punish a character for specializing in ranged attacks in the name of realism. You can’t use shields except under very specific circumstances, you have compounding penalties to hitting a target that’s moving at an angle to you, and you can’t move and shoot unless you’re a horse archer. Thankfully for archers, you have no downside to your impaling attacks and can fire off attacks at rapid speeds.

I forgot that there's sentient baboons in Glorantha.

Shields, Helmets, and Armor

In RQ2E armor absorbs damage, rather than acting like the all-or-nothing system of AC that’s in D&D and its design family. Since RuneQuest uses a hit location system, each section of body armor is accounted for separately and you can mix and match components (and even stack a few types). This is mostly balanced by the fact that each armor segment takes up encumbrance and gives a stacking penalty to moving silently.

And that’s it for Chapter IV! We finally have all the mundane rules for how to murder each other, though they were spread across the last few chapters. In addition to this, the skill system based on experience and training that has come to characterize BRP character advancement over the last 4 decades is established here in a fairly unified way. Would you believe that so far I’ve only covered 33 pages? I don’t.

Next Time: Chapter V, Basic Magic!

Basic Magic, Part 1

Original SA post

Perhaps the real RuneQuest was the friends we made along the way!

Previous Review Sections

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: A Brief History of Godtime

Part 3: A Brief History of Time

Part 4: Chapter II, Character Creation

Intermission 1: Creating Goonalda of the Lowtaxanoli Tribe

Part 5: Chapter III, Mechanics and Melee

Part 6: Chapter IV, Combat Skills

Chapter V: Basic Magic, Part 1

”Chapter V” posted:

Basic Magic is available to all players in RuneQuest. There are two types of Basic Magic: 1. Battle Magic; and 2. Spirit Contacts.

Battle Magic

Within the game, Battle Magic’s two major mechanical characteristics are that they 1) work on a very short term basis, and 2) take a comparatively high amount of POW compared to similar effects within other magic systems. You’re essentially brute-forcing reality, and without a easy access to Glorantha’s Otherworlds though means like being a member of a divine cult, having spirit contacts, or being a shitty wizard,* it’s highly inefficient. However, unlike these methods, conceivably anyone can learn some battle magic. Additionally, the rules for Battle Magic are the basic rules that all other systems are based on, whether through exceptions to the rules or by defining themselves in contrast to them.

Anyways! Your POW score determines how much magic you can do, though unlike the other stats, it also goes up and down frequently as the ability score doubles as the character’s “MP.” POW regenerates up to 1/4 your maximum POW score every 6 hours. Again, this is an example of in-game time keeping becoming a critical aspect of game balance like we’ve seen in previous chapters. This brings up the issue of POW acting as what I’d like to call using RQ2E’s nomeclature “multiple implicit abilities,” because so far we’re seeing that POW can both mean your maximum MP and your current MP, and it also defines an MP regen rate. This is a bit of an issue in terms of clearly stating all aspects of the system, but I suppose in 1978 the concept of magic points was novel enough that explicitly separating them in the game language didn’t seem like a necessary action.

Adding to this is the additional headache that arises from a constantly shifting POW score– many of a character’s abilities are affected by their POW, and so any major use of magic will involve recalculating a lot of different stats if played RAW.

Characters don’t start out immediately knowing spells. That doesn’t mean that a character without spells doesn’t need to worry about Battle Magic, because every character uses their POW to repel enemy magical attacks. When characters cast spells on a target, the relative POW of the attacker and defender determines the base % chance of the spell successfully working (remember, RQ2E uses a percentile system as much as it can for its conflict resolution!). Unlike with melee combat, it’s possible to immediately overpower the defender, or automatically resist a spell– for example, our Goonalda ignores or overpowers 7 POW enemies with magic because of her 17 POW. However, the POW compared on these tables is your current POW, rather than your maximum POW. It’s a clever system, but from reading this it seems like the magic system’s “meta” would immediately default to baiting your opponent into attacking first so that you have an advantage on your counter-spells.

Pictured: a PC reevaluating their previous spellcasting choices.

Learning Spells: Just Take a Few Classes At Ishtar Temple Community College

Going back into the order of how things are presented in this book, spells are learned like anything else in RQ2E: paying a guild (a “rune cult” in this case) to teach you during your character’s downtime. Battle magic is widespread enough that any given rune cult will have access to all spells, which makes things fairly simple for the player. Much like with weapon skills, starting characters are given “guild credit” for some basic starting spells, though in this case this credit scales with your character’s POW. I guess in the world of magic, game recognize game?

Alongside the financial and downtime limits to learning spells, there’s a personal limit, too: characters can’t have more spells active than their INT score allows. Many battle magic spells have multiple ranks (healing 1 to 4, etc.), and these count as a number of “spell slots” equal to their rank– these are called Variable Spells in the game. So, you can either know a lot of low-level spells or a few high-level ones. You can know more spells than this and use them at different ranks, but the total number of active spell levels can’t exceed your INT. This seems like a strange hybrid of AD&D’s “Vancian spellcasting” with a magic-point spell system, where instead of a spellbook, each character has an “active spell list“ they can use at a given time. It’s also important to remind us here that all characters are doing this to some extent, not just a single class. Every PC in RuneQuest uses magic.

A Bunch More Details on Battle Magic