Leverage: The Roleplaying Game by neonchameleon

| 1 | The Opening |

| 2 | The Crew |

| 3 | The Job |

| 4 | The Fixer, part 1 |

The Opening

Original SA post

I'm going to come out at the start of my write-up and say what I expected to find when I bought the Leverage RPG in hope was a horrible mishmash of a game. What I actually found was a game right up there with Dogs in the Vineyard and Spirit of the Century. Obscure, yes. Mockable? Not very

Get ready to get even

So what is Leverage? For those who haven't seen it, it's a heist/con/caper show involving five screwed up characters, a lot of research from the writers, and some really quite sneaky cons (some of the time anyway) and characters who are spectacularly competent at what they do.

A quick glance inside at the opening credits shows something that looks highly worrying. Cortex system. The system that brought us the d12+d2 stat, as well as four derived attributes and a possible three specialties for each of the twenty skills

(the character sheet isn't quite as bad as a GURPS one, but comes close)

So we are expecting a detailed system with very high variance (seriously, check those target numbers out). But there is a huge ray of hope. On the design team: both Fred Hicks and Rob Donaghue (of Spirit of the Century).

Foreword

quote:

All we want to do is set the world right.

I mean, think about it. We roleplayers get together in living rooms and classrooms and garages all around the world, and we tell these infinite stories about infinite worlds and they all have one thing in common. Your sword-swinging barbarian and your lightning-throwing steampunger and your neuro-cyborg all have the same job: they fight injustice. Soemtimes they do it for a pocketful of money, don't get me wrong, but in the end the world's a better place for your hero's presence.

Sometimes I think that roleplaying is an echo of the old morality plays. In the end, we crave an ordered universe. A universe where good deeds help you and bad deeds don't go unpunished. And what happens really? Good deeds go unremarked, and bad deeds are scarcely noticed. We live in a world that confounds our sense of decency. Even more so, our sense of control.

A good opening to the foreword - the rest of the page is about Leverage and the Robin Hood part being important for heist and con shows. (This page is written by John Rogers, Executive Producer and writer of the Fell's Five D&D comic).

Chapter 1: The Pitch

A nice clear chapter asking questions like

What is Leverage?

quote:

Leverage is the story of a group of thieves and confidence men who choose to use their expertise to take down bad guys the authorities can't - or won't - take down themselves. It's at times light-hearted and comical, other times intense and tragic. Every job the LEVERAGE [sic] Crew takes on brings to light more of their criminal backgrounds, their unparralleled skills, and their need to trust one another in a very untrusting world. As their clients are avenged and the Marks brought to justice, one way or another, we see more of the shadowy world of crime that exists alongside ours.

What is a Roleplaying Game

I think we all know the answer to this one if only by bad example here. This pair of pages (have I mentioned after reading D&D books I love the graphic designer here?) also has subheadings that outline what the Leverage RPG is about

* A Team of Experts who rarely fail at what they are supposed to be good at.

* Bad Guys Make The Best Good Guys - it's about conmen and thieves trying to turn over a new leaf.

* Flashbacks and Fail-safes - the first mention of the flashback rules that will appear later.

* Seriously "If you can't have a good time catching the crooked Chairman of the board with his pants down, what's the point?"

What's in this book?

This section is almost a surrogate contents. It lists the chapters then explains why they are called what they are and what they contain. I don't think I've ever seen another RPG be as clear at this. For the record.

1: The Pitch - we just had it

2: The Briefing - the basic rules

3: The Crew - Character Generation

4: The Job - how to actually play (goes way beyond chapter 2)

5: The Fixer - How to GM. (The Fixer is the game-name for the GM)

6: The Toolbox - Useful ways to make things up on the fly for the Fixer.

7: The Crimeworld - How to think like a criminal, how to run a con, a list of classic cons explained, other useful stuff.

8: The Record - Synopses of S1 and S2 of Leverage to either loot for ideas or just pad the page count.

Thoughts on this chapter : Either this is the cleanest, openest, and best laid out RPG I think I've read, or they've found an excellent way of padding the page count without actually saying anything substantive. The lines are all double spaced, and spaced with pictures of the cast (every double page so far has had at least one), making it extremely easy on the eyes. The promises are good, but the delivery remains to be seen (there's been literally no delivery in the first chapter).

Chapter 2: The Briefing

We all know what RPGs are. THere's a bit of cute jargon here (like calling the Character Sheet the Rap Sheet, and splitting Supporting Characters (NPCs) up into Marks (big bad guy targets), Agents (the bad guy's minions), Foils (rivals), and Extras (the rest). But nothing special on the first page.

Attributes: It's the Cortex Six (Agility, Alertness, Intelligence, Strength, Vitality, Willpower). Nothing special.

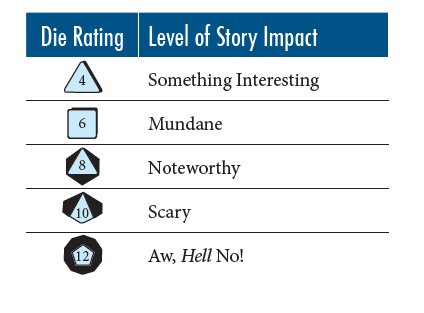

Roles: The five roles from the show. Grifter, Hitter, Hacker, Mastermind, Thief. These replace skills - anything you do should fit under one of these roles. Which means everyone has at least a little skill in everything - and the skills are broad . You also get specialities within the role which add a d6 to your roll - but it hasn't yet told you what you roll, when, or how.

Distinctions: And now things get interesting. Distinctions are "descriptive traits that fall outside the area of attributes and roles. ... They can either help you or make life difficult for you - or both..." So they're Spirit of the Century style aspects then. "...but you decide which is which and when." So not aspects. They are like aspects but entirely under the control of the player. Now things are getting interesting.

Talents: Spirit of the Century would call them stunts. Nothing special here.

Assets and Complications: Assets help the PCs. Complications hurt them. You create assets by spending plot points. Yada yada. "A complication comes up as a result of rolling a 1 on your dice, which is why the smaller your dice the more likely things are going to be to get ... complicated." Wait, what? We've a full blown yes-but system here. Where you can succeed and create problems at the same time just from your dice rolls.

Mechanics : It's a dice pool system. One dice for stat. One for skill. One for a relevant distinction (d8 or d4 - you gain a plot point for the latter). Drop the 1s then take the best two (or more if you spend a plot point). Opponent then decides whether to give in (losing but getting narration rights) or raise the stakes (rolling to try to beat the score - but gambling the chance of both losing and losing narration rights). A raise by 5 is an outright win and gets the narration rights.

And then the chapter ends with a section on Collaboration and Responsibility including a list of bullet points on what the players are responsible for, what the fixer is responsible for, and what everyone is responsible for. Why can't all games have something like this?

Thoughts on this chapter : I swear this book would neatly fit into 50 pages if you took out the padding, assumed it was written for experienced roleplayers, and removed the pictures. That said, the mechanics show a lot of promise - I don't think I've seen a more elegant system that had the chance of succeeding and being unlucky, and you normally get more than one bite at the cherry if you roll badly which should compensate for the swingyness of the dice pool. I'm going to leave the final line of this chapter as a signing off quote.

quote:

Everyone is responsible for

...

In general, making everybody else at the table look awesome

The Crew

Original SA post

Part 2:The Crew

The crew, the party, the team. Call it what you like, this is about Character Generation.

quote:

LEVERAGE Crews are recruited with aclose eye toward how well they work together. If you do this process in isolation, you get crews that don't mesh together. Crews that aren't together turn into what we in the business call "prison inmates". Let's try to avoid that, shall we?

There's a seven part shared character generation method in this chapter and a fast one. The fast one is summarised on the bottom of the Leverage Character Sheets ("creation: assign 2d10, 2d8, 2d6 to attributes. assign 1d10, 1d8, 1d6, 2d4 to roles. create 2 specialties. create 2 distinctions. choose 2 talents."). Have a look at that character sheet - it really is that simple. (And compare it to the Serenity character sheet ).

Recruitment steps:

1: Get a blank Rap Sheet . Becaue everyone needs a character sheet.

2: Consider your background . Just what it sounds like.

3: Assign your primary role . What are you the best at doing?

4: Assign your secondary role . What are you pretty damn good at doing?

5: Assign your attributes . Simple allocation. Six stats mentioned above, either 2 each at d10, d8, and d6 or 1d10, 4d8, 1d6. (Quick generation only has the one method).

6: Compose one distinction . A FATE style aspect as mentioned earlier. You're going to end up with three.

7: Play through The Recruitment Job . The Recruitment Job is a cut-down mission - and in it you will get to decide one distinction and two talents - and the rest of the table decides your third distinction.

A useful way of both starting the game and getting everyone onto the same page - you've only painted broad brushstrokes of your character before you start playing. It then goes on to the roles. Each role has about two pages (with the layout here I wonder why they didn't do a double page spread) explaining what it means and a paragraph on how it works with every possible secondary role (each with a name).

The Grifter : The Conman or Conwoman. Sophie or Tara from the show, Face from the A-Team, or any other conman you can think of.

The Hacker : The information specialist and tech geek. Q from James Bond would be a hacker (and I don't just mean the Q in Skyfall).

The Hitter : He hits stuff. Hitter is the role you use in combat and your Hitter is either your enforcer or your exit strategy (when all's going wrong with the con change the game). There's a sidebar giving reasons not to use firearms.

The Mastermind : "I love it when a plan comes together." Yes, Hannibal is a textbook Mastermind.

The Thief : You gotta pick a pocket or two. Or play with the laser motion grid, open the safe, jump off the building just held by a rope, or any other such stunt you can think of.

Those are the five roles (hint: If you've only got four players drop the Hitter). They are taken directly from the show - but they work pretty well for a range of groups. As an interesting touch (I'm not sure whether I like it or not), the gender used in the text matches the gender of that character on the show.

Stats: The six Cortex stats and a box marked "No Charisma Attribute?" explaining that there's no one single charisma attribute because it's too broad for that. Nothing really to see here.

Talents : It's a description and list of talents. They're all on the rap sheet I linked above - you need half your talents associated with your primary role (so one out of the two a starting character has). Some of the talents, oddly enough, work better with people who have different roles ("How YOU Doin'?" adds a d10 and a d4 to a flirtatious face action - the Grifter probably doesn't need it, but it can make a hitter or a thief, while "I can kill you with my mind" is a hitter talent allowing you to add Int to a combat role and keep a third dice - probably best for a Mastermind or Hacker). There's also a section on "Constructing your own talents".

Distinctions : This section's disappointing. They recommend single word distinctions so Nate has as a distinction "Drunk", "Honest", and "Controlling" rather than something more interesting like "Functional Alcoholic", "An 'Honest Man'", and "Keep to the plan!"

The Recruitment Job

This is a proto-mission designed to get everyone comfortable with the game. Three offered basic problems and thre offered basic solutions. ("Stolen Goods", "Hurt Client", and "Fraud Victim" as the problems, and the solutions "Steal the MacGuffin from the Mark", "Con the Mark out of the MacGuffin", and "Get the Mark to self-incriminate"). Incidently, the game implies that before you reach this point the Fixer probably won't know who the first Mark is.

The mini-session is going explicitely to be made up of "Spotlight Scenes" and "Establishment Flashbacks". Spotlight Scenes - each PC gets one scene in the job to show off and use their skills. Each crewmember designs their own scene . (They may also establish one or both talents within their scene or anyone else's where they are involved). Establishment flashbacks: Each PC gets a few that can either be used to establish distinctions (chosen by the other players) or to establish talents or specialties. How/why do they have these talents? It's entirely possible to have things unspent by the end of the job.

So Chargen is a mini-adventure (one without a twist half way through). Or you can do it fast - we've already recovered fast recruitment.

Benefits of Experience

Or as we like to call them XP. For each job you do you get two benefits. 1XP and a Callback in one session. A Callback can be used once, referencing a previous job, and gives you a plot point. XP: A signature asset (a 1d6 item that you keep or repair from job to job - your first is 1d8 rather than 1d6) costs 1XP, adding a new specialty (a 1d6 trick) costs 2, adding a talent costs 4, and stepping up an attribute or role costs 8. There's also a section on allowing you to retain if you're not getting benefit out of something (quick version: If the Fixer thinks it hasn't come up he should say yes, if he thinks it has he should pitch straight to it in the next job and only if the player turns down the opportunity to use it does the player retrain).

Sample character sheets - Sample characters for all six of the Leverage crew counting Tara (Gina Bellman became pregnant so they wrote Sophie out for half a season and Jeri Ryan's Tara in as her replacement). And yes, all of the crew work perfectly well under the rules as starting characters.

Thoughts on this chapter: So that was character generation. 45 pages. Continuting with the theme of pretty awesome, explained in great depth, and very padded. But even if the padding quadrupled the size and cost of this book it's still only hardback RPG price and is capable of taking on a game like Spirit of the Century on its own turf. Also for the next 24 hours or so it's part of the Drivethru RPG sale

The Job

Original SA post

Chapter 4: The Job

This section is the advanced rules. Back in Chapter 2 (The Briefing) we had the basic rules of the game. Ths section starts with how to decide what dice to roll (what looks best - it explicitely says "speed trumps fidelity") or for the Fixer (anything you've established or d6s if you haven't). Locations get traits the same way NPCs do - in both cases they are opposition to the party (mostly). And the PCs can sometimes take advantage but they are normally not on home territory.

Well that's easy enough to visualise. Normally rolling two dice, sometimes more. And there's advice that the dice isn't the only thing that matters - for instance freight train and motorbike might both be d6 rated traits but this doesn't mean they have the same effect in a head on collision. As a rule this is the fixer's call - add an extra dice or two for minor advantages, keep an extra dice for major ones, don't even roll for absurd ones.

quote:

Example

Let’s look at cars, as they’re a pretty common example of this sort of problem. Let’s say you have a Crewmember chasing a bad guy, and they both hop into cars, but the bad guy jumps into a suped-up ride while the Crewmember hops into an old junker. In the strictest sense, the bad guy’s car is faster, but the race doesn’t always go to the swift. This discrepancy can be handled by giving the bad guy a SPORTS CAR D8 and the Crewmember an OLD JUNKER D4. The difference in cars is an advantage, but since both sides are in cars, it’s still a reasonably fair conflict.

In contrast, imagine the bad guy hops into his car and peels away and the Crewmember is left with nothing but his own two feet. What happens next depends on the situation. Let’s say the Crewmember knows where the bad guy’s going. If it’s a few miles away then, well, he’s pretty much hosed. There’s no way he’s going to get there first, there’s no point in even rolling the dice.

Suppose the destination is only just across town, through traffic. Sure, the bad guy’s got an advantage, but it’s not impossible that the Crewmember could pull off some sort of crazy parkour-style montage, cutting down back alleys and running across rooftops to try to get there first (that’s parkour, or free-running, not Parker…just to be clear). It’s doable, but pretty darn hard, so the bad guy gets a bonus. He’s a SLEAZY D8 SLEAZEBAG D6 in a FAST

CAR D8. Normally the Fixer rolls those three dice and adds the two highest together, but for this roll the Fixer totals up all three. For the math-heads among you, this means he gets an average result of 12.5 and might roll as high as 22. Even if the Crewmember has 2d10 to roll, there’s no guarantee this goes well for him.

Well that's pretty clear. At least to me.

Assets and Complications

An asset is something the crew member wants to make notable. Even a tray of hors d'oeuvres. Spend a plot point and you get a d6 asset for the scene, two and it's d6 for the rest of the job. Assets, because they refer to something tangable, can be problems and rolled by the fixer (a Big Knife D6 might have been useful earlier - but it's a liability when the police show up is the canon example). If you don't declare something an asset you can still use it as a special effect (no extra dice).

Complications are the consequence of rolling a 1 on your dice. A tangible anti-asset. At d6 for starting rating they are almost certainly underrated and should be d8. The complication doesn't have to apply to the crewmember rolling the dice - but they are tangable and can be dealt with.

Actions, Scenes, & Beats

Narrative pacing. A beat is one roll of the dice, however long it takes in real time. It's a decision point.

quote:

Example

Hardison sees thugs approaching on the monitor and slips out the window. One of the thugs spots him, and they chase him through the parking garage. He hides behind a dumpster as the thugs rush past. He then decides to trigger every car alarm in the garage, forcing the thugs to flee to avoid the unwanted attention. This is a pretty good scene, and it’s composed of four beats:

1. Hardison spots trouble and flees

2. Thugs spot Hardison and pursue

3. Hardison hides behind dumpster

4. Hardison triggers car alarms

Do you see how each beat is a single event or exchange of events? If the chase had to cover other locations, there might have been more beats, and if the thugs hadn’t spotted him, it would have been only a single beat. It’s hard to predict exactly how many beats there will be in a given scene, and you don’t need to stress yourself trying to do so—that’s not why they’re important.

Again clear - but there's no indication why we actually need to talk about beats at all.

Basic actions, contested actions, timed actions

Basic actions are a single roll. Fixer rolls first. Examples given. Contested actions are contested and were largely dealt with in chapter 2. Fight scenes and how to handle extra thugs (one extra dice per helper, each raise of the stakes automatically takes out a helper) are given two pages - and are the only contested action illustrated in detail. Timed actions - you get a set number of beats. Spectacular successes take either zero beats or if you're really lucky can have a shortcut. Simple - and for the first time in the book I don't think there's enough advice on how to set how many beats.

Flashbacks

One of the signatures of the show. Establishment flashbacks are mechanically the same as spending a plot point for an asset and describing it. But they can have a far bigger impact than this.

quote:

Example

Parker’s in a desperate standoff and the Mark’s holding the Client at gunpoint, threatening to kill him. Parker’s player spends a Plot Point to flashback to Parker’s earlier break-in to his office where she finds his gun in the drawer, removes the bullets and puts it back. The Fixer rolls d8 + d8 (hey, it was a locked drawer). She rolls her Alertness + Thief. If she rolls less than or equal to the Fixer’s result, the Fixer describes a flashback to the Mark checking his gun, frowning, and reloading it. If she rolls higher, the Mark’s gun isn’t loaded and Parker now has an Asset like You’re Firing Blanks d6.

Well yes. That asset does do that. It also means that when the mark pulls the trigger he fires a blank. Really powerful. And fun.

Wrap-up flashbacks are for the final dice-off between the Mastermind and the Mark. The final chance for the crew to all show how they contributed to the downfall - and to pass an asset for the mastermind to use in the dice-off that wraps up the caper.

Summing up

This chapter was straightforward, necessary, useful, and the only chapter approaching boring so far. Not too much you can do to a mechanics resolution chapter - advice for players, worked advice, and just about everything you'd expect including the padding - it's also the end of the player section of the book. Although the final paragraphs to wrap this chapter up in the book are lovely.

quote:

The Fixer, on the other hand, still needs a bit more training. That’s what’s coming next, in Chapter Five: The Fixer and Chapter Six: The Toolbox. Those chapters talk about how to create capers for the players to run through, and give advice and examples of non-player characters, locations, and situations for the players to encounter. Under no circumstances should the players read those chapters.

And if you, as a player, don’t immediately disobey that last advice and go read those chapters, you’ve not yet adopted the correct mindset for the Leverage RPG. Go steal yourself a roleplaying game!

The Fixer, part 1

Original SA post

Chapter Five: The Fixer. Part 1

My last chapter ended up with the PCs being told that they were not on any account to read the Fixer's (GM's) chapter - and then telling them that if they actually followed that advice they were playing the wrong game. It was also a fairly simple and mundane chapter on the rules.

I don't believe there's a single rules mechanic in the entire 40 pages of Chapter Five. Instead what it is is an entire chapter simply made up of GMing advice assuming that the GM is (a) new to the game and (b) certainly hasn't tried to GM a heist before, let alone an entire episodic series of them. And heists are difficult enough to GM (especially with games that aren't designed for them)

Crooks and Capers: The Heist Genre

The first major section in the Fixer chapter starts off with a discussion of what a heist and a Caper is. You probably already know about both - and I've linked Wikipedia if you don't. It then goes into the three act structure of a classic heist, why Leverage doesn't use the traditional third act (the team may be crooks but they have hearts of gold and don't turn on each other), why it uses a five act structure (commercial breaks - no, really), and what those five acts actually are.

quote:

1. Something horrible happens and the innocents affected approach the Crew for help.

2. The Crew researches the caper, and the Mastermind pitches a solution to the Crew.

3. The Crew sets the caper into motion but stumbles into a complication that they can’t ignore.

4. The Crew overcomes the first complication but encounters a much bigger complication. By this time, they’re in too deep to consider walking away.

5. The Crew overcomes the largest complication and gets away with the caper. This is often capped with restitution given to the innocents who were introduced in the first act.

And then it finishes this section with the advice to keep things light even while dealing with serious matters (as you expect to be because some of the villains are very nasty).

Creating a Job

The last section was very basic advice about Leverage and capers. This is much more practical advice - what do you actually need to run the story. At this point it mentions the next chapter - the Toolbox - which can give you an instant story. But if you don't want to do that it breaks things down into where to start; whether you start with the victim, the problem, or the mark and why you might do each. Something you need to get the caper started. (Of course you can't start with the solution because that's the Mastermind's issue, not the Fixer's). Basically it boils down to "Pick something bad happening and go from there.

The Big Questions

Or what elements do you need for the con? Each of the bullet points below gets about a column to itself explaining why it matters and giving half a dozen to a dozen possible options.

-

What Is the Problem?

- what's going wrong?

-

Why Come to the Crew?

- why won't e.g. the cops help?

-

What’s the Mark’s Angle?

- why is the mark a villain? What does he want.

-

Why’s the Mark Untouchable?

- why hasn't the mark's shady dealing come back to bite them? (Suggestions: Rich, Powerful, Connected, Smart, Scary0

-

What’s the Mark’s Weakness?

- what are the PCs going to exploit?

-

Where’s the Mark Vulnerable?

- the mark is going to fall and fall big if the PCs are on form. What's going to come crashing down?

-

Who Else Is In Play?

- no one is an island. Throw a few supporting characters in to the mix

- Changing it up - once everyone's happy with jobs a few more things you can do, like making it personal or for once making the team play defence.

All very good questions to ask, and after this section we already have a structure ready made for a story. I've seen books on writing giving a lot less practical advice than there is in the few pages.

quote:

Sharp eyes will notice that each of these questions has a list of sample answers that are fairly general. If you’re in a hurry looking for inspiration for your Job, just run through the questions and pick one answer for each question and see what that suggests to you.

Planning the Heist

Only an utter pedant would bother to point out that this book is well enough presented that there isn't a heading here and Settling on an Endgame is a subheading under the previous heading as an actual mistake. So I'm going to do so. Yes, the mistakes in this book are of that level. I also think this section is more intended for the Mastermind than the Fixer - but I'd sumarily fire anyone who thought they could play a Mastermind who didn't read the Fixer section even more carefully than the players' section. (If a Thief or Hitter doesn't have the instincts to read this section, who cares? They are going to look awesome anyway. But the Mastermind certainly should).

-

Settling on an endgame

- The first thing to do for planning is work out the mark's fall.

-

The Fix

- does the mark's fall actually solve the problem? If not, rethink or tweak.

-

Create Openings

- "figure out how

people

fit into the plan." And then how you can get the crew into the right place.

-

The Point of Leverage

- how exactly are things going to go wrong?

-

Build the stage

- Location, Location, and Location. 'nuff said. Other than that it suggests you might want a list of stock locations.

- What can go wrong? - Muahahahaha. Three full columns of utter mayhem.

The Briefing

Here again, the copy-editor messed up. The Briefing should be in slightly larger type marking it as a section heading not a subheading. Bad copy-editor, no biscuit. And seriously, by the standards of the rest of this game's presenation mistaking headings and subheadings is a major mistake. (The only other one is that I can't work out quite how the contents works; it seems to be keyed to the inset text boxes.)

-

The Pitch

- The sob story. It mentions that this is optional and can be rolled into the Presentation

-

The Presentation

- the infodump the players are going to need. You might give it to the players or give one of the players your notes to present to everyone else. Or even "The Contested Presentation" - which is an info-gathering montage (the Fixer rolling 2d8 each time) before giving the players the answers to

most

of the questions above (losing one for each complication or fail). Leverage really does provide tools to run on the fly with the Fixer having no idea in advance what the crew will know about their Mark.

-

Planning

- The players need to plan their heist. And it explicitely tells the Fixer to not be stingy with answers - the players are meant to have the information they need.

-

The Presentation/Planning Cycle

- the players might need to go back to the drawing board on their plan, with their first plan being to get enough to make a takedown plan. This is a thing.

-

Getting On to the Action

- Good plans are best cooked rare. So it tells you to:

-

Skip Right to the First Cool Thing

- of course you do. Why waste time?

Let me just run through The Contested Presentation with its montage.

quote:

. Run through the list of Big Questions from page 84 in this chapter and write each one on the back of an index card, with the answer on the opposite side. Separate out the questions about the Client and reveal them to the players. Mix the rest of them together into a pile, and then ask them what the Crew’s doing to look into this. For each description of an action, let that player roll appropriate dice against your 2d8. If they succeed, reveal the top card to the players. If they generate a Complication {roll a 1 on any dice}, remove a card at random from the stack. If they fail, remove any card you choose from the pile.

At the end there should be a pile of cards revealed to the players and a smaller number of cards in your hand that the players haven’t seen. Look them over

and think about why they’re obscure—these are the potential twists in your game, and the fact that the Crew’s uncertain about them is an open door to trouble. You may then complete the briefing by telling the Crew the answers on your cards, or rather, telling them some of the answers. For at least half the cards, you should make something up. (this is why you tell your players, but don’t show them the cards). Over the course of the Job, you can flip your cards over at dramatic moments to reveal that the Crew’s on track, or to reveal a twist.

Anyone up for a challenge running a game? I am.

The Job in Action

You've set it up and planned it. So now there's actually running it. How much do you let it unfold, and when and how do you derail it? After all too easy would simply be boring. You roll when you think a disruption would make things more interesting or fun. A lot of this section is good general RPG advice.

-

Handling Failure

- Fail Forward. It doesn't actually use those two words, but that's what it amounts to.

-

Spread the Focus

- Make sure no one dominates and no one's left out.

-

Timed Actions and Spreading the Focus

- Timed Actions shouldn't be used to adjust difficulty. They should be used for synchronisation and tying things to everyone else.

-

The working plan

- think of a few scenes that let the crew put things together. "It's a shame it never goes like that"

The Twist: The Plot Thickens

What's a twist? I think we all know the answer to this. And it would be boring to not have twists. So twist when things look like they are on course. With anything you kept hidden - or something you came up with that flows from the narrative.

The example twists open with a set of twists never to use and reasons not to.

-

Betrayed by the client

The party is going to turtle like crazy and research to levels of boredom. Instead use "The client is not what he appears to be" - and the party finds out soon enough to prevent it being a trap.

-

It Was a Trap

The party doesn't just turtle on all future jobs. They dig a hole and pull it in after them. We want fast fluid play. Instead use "The hunter hunted" - the crew spotted the trap, or "The opportunistic bad guy" - the bad guy spotted a mistake. Don't poison the bait.

-

Old friend gone bad

. Ever wonder why there are so many orphaned RPG charactes with no surviving family. This cliche. Instead try "The right choice"

-

It was SO OBVIOUS

. If you want something to be obvious, just tell the players.

-

En Passant

. No the PCs aren't dancing to the NPC puppetmaster's tune all the time without knowing it. That's just annoying. Make them knowing pawns and give them a chance to hit back if you want this.

Why Twist?

It's interesting and fun. And paces the game to the right length. Nuff said.

Clear direction

If the PCs are looking at each other after the twist and saying "Now what do we do?" you've messed up. Try the following:

-

Tangental Twists

Twists that don't change the end goal. Merely add extra players or complications - such as a rival crew. Always good.

-

Problematic Twists

Twists that demand a solution. Assassins are an obvious one - they change the goals, but there isn't the "now what" issue.

- Informational Twists If the PCs had incomplete information and knew it, finding it will prevent a screeching halt.

And sometimes it fails. Keep going. And add new twists depending on how long your sessions are.

The Solution: When The Mark Goes Down

Normally it will work. Sometimes it won't and it doesn't. And sometimes it's close but not quite there. If it's close but not quite there you've a solution to make the wrap-up much more satisfying that doesn't feel like cheating (although can feel coincidental). Fudge the in-game timing. And because no one likes missing out the mark going down you do two things. First make sure there's a crewmember there as witness. Second give the players NPCs to play rather than talking to yourself.

Dénouement: Wrapping It Up

Have fun and give everyone time to enjoy.

That's the end of the high level overview - but there's more in this chapter. Some much lower level specifics are still to come in this chapter, and one of my favourite text boxes ever.

quote:

Hey, Player.

Yeah, you. We both know this is the Fixer chapter, but we also know you’re reading it anyway to get a leg up. That’s smart—you’re already thinking the right way. So here’s a tip: you want to pay special attention to this stuff about beats if you want to run a con on your Fixer. See, the truth is this—he’s going to be running things fast and hard, and when that happens, he’s going to tend toward the path of least resistance. That means if you can provide him with a plan that already does everything he needs (like hitting a beat for each Crewmember) then he’s going to be happy to roll with that, and

it’s that much more likely to work.

If you’re feeling really tricky, start suggesting problems you might encounter before the Fixer starts coming up with them. Why? If the Fixer creates a problem, you’ll need to figure out a way around it, but if you create the problem, you can build it with a loophole. Just phrase problems as, “We’ll need (Crewmember) to (do something) to avoid (problem).” Again, you tap the Fixer’s laziness to guarantee that you’re on the right track.

Getting Your Hands Dirty

Actual specific tricks for the fixer within the scene:

-

Plan the Scene in Beats

- each beat, as defined earlier, was something to accomplish. A narrative not chronological unit. And the beats (example given: a safe with a password not a padlock so someone other than the thief could handle it) allows you to introduce other players.

-

Beats and Complications

- the players will take time to deal with complications before they explode.

-

Death by Reconnaissance

- games derail when the players don't know what to do so they gather information without knowing what they are looking for. Twist or give them it. And don't do pixelbitch searches. You've a thief to grab things.

Assets and Complications

Both are things . And are most of what you need. Use them - and complications and twists are closely related. Treat them as things - and as dice ratings. A complication of "This door has been nailed shut" (d8) can be overcome by brute force (just hope the thief can hit)

Design Vs. Discovery

A.k.a. How much do you run on the fly and how much do you plan in advance? There's an awesome worked example of on the fly play here.

quote:

Consider, for a moment, how Sterling is introduced in the TV show. When we first meet him, we don’t know much about him, but over the course of the episode and subsequent episodes, we get a fuller picture. Now, imagine this in a game from the Fixers perspective; this might be because he had already written up Sterling and he reveals him over time—that’s certainly the normal assumption. But what if, when he started, the Fixer didn’t know any more about Sterling than the players did? He’s just Insurance Investigator d6 at the outset, but the Crew decides to mess with him, gains a Complication, and suddenly he picks up Evil Nate d8 as a Trait. Over the course of play, he picks up other Traits, like Bastard d8 and Opportunist d8 (and maybe gets Bastard bumped up to d10, just to be thorough) and after a few sessions, Sterling is a well fleshed out character, created entirely through play. This

is just one example, but a Fixer who enjoys flying by the seat of his pants can build almost anything this way.

Shifting the emphasis - not much to say other than this is making something that was already there more prominant. Yes, the goons were already armed - but the Well Armed (d8) complication means it matters.

Working Without Complications - A thing that matters is a generic d6. Good general rule.

And there's still more "The players are meant to look awesome" advice.

quote:

Complications and Player Cleverness

Every now and again your players are going to surprise you with some judo. They’re going to take a Complication you introduced as a problem for them and use it to their own advantage. This can be very surprising the first time it happens, but there’s a good chance it’s going to keep happening, depending on the style of your players.

You might feel an instinctive desire to refuse to let them do this—that somehow this is cheating. If so, you have to tamp that instinct down, because it’s absolute poison. Your players are interested in capers and heists, at least in part, because they want the chance to be cool and clever. The ability to turn an obstacle into an Asset is exactly that, and you need to be able to celebrate that. Acknowledge their cleverness, and come back swinging

Sample Complications

Just because lists are good for inspiration. Each of these has a description as to why it's good.

-

The Parade

-

The Camera Crew

-

The Hot Chick/Dude (also mentions they may later pick up the Undercover Agent complication for added mayhem)

-

Child in Danger

-

Blackout

-

Weather

-

The Repairman

-

The Actual Guy (the PC is masquerading as)

- The Concerned Citizen

Assets

What are assets? Simple. Something the players want or want to make a big deal of. Either because they can think of a way to look cool (using a plate of hors d'oeuvres for a fight scene), they want it there (it ducks "Mother may I"), they want to emphasise soemthing (a "Pissed off" d6 asset on themselves) or they want to subvert (a "Having second thoughts" asset on a gunman to allow the grifter to talk them down). The players get to direct for a bit and unless it's utterly unreasonable, say yes.

Your Players Are Up to Something

If you can't see why a player created an asset, wait. It should be good when it comes good. It's probably an exit strategy. And it's also likely to be worth looking at under the Really awesome assets rule (a paragraph saying if they impress you give them a d8 not a d6).

Still more on assets for people who aren't used to games where the PCs get any sort of narrative control. And of course

Sample assets

-

Rappeling gear (yes, it's a d6. It also lets you

jump off buildings

)

-

Duct tape

-

Caffiene Buzz. Hardison, step away from the coffee pot.

-

Distraction

-

The latest hardware.

-

The Right Clothes

-

A clipboard (because where can't you get with one?)

The Players’ Bag of Tricks

Plot points, assets, flashbacks. Just over a page showing the fixer not just what they can do but how to handle them. And yes, you can flashback to fix a failed flashback. Or to Rashomon Job.

Pulling it all together

Normal rule of good writing. this is two pages telling what they just told us. It works.

*******************************************************************************

Whew! A lot of material and good advice in 40 pages of widely spaced type and photos from the show, and barely a rule to be seen.

On a complete tangent and possibly for my To Do list - has anyone done a write-up of Diana: Warrior Princess yet?