Legend of the Five Rings 5e: Emerald Empire by Mors Rattus

honestly, pretty impressive

Original SA post

Emerald Empire is the first released supplement for FFG's line of Legend of the Five Rings books. I covered the beta way back when it came out, and...well, the mechanics are all pretty similar to what they were then. Some tweaks, dueling got redone some, some stuff got renamed (strife explosions are now called something else and are technically optional, but if you don't have one when you're full up you get huge penalties). But now we get to see in detail their take on the setting, and it is...honestly, pretty impressive. For example, this book is the first time Legend of the Five Rings has ever actually detailed a lot of the stuff that goes into playable day-to-day of the Empire, such as how shrines are actually treated or what castles are really like.

The book is divided into seven chapters. Chapter 1 is about castles and palaces, both as forts and as political centers, and also discusses diplomacy and war. Chapter 2 is about cities and towns and their role in trade, as well as harbors, ports, crime and law. Chapter 3 covers villages and farms, roads, rivers and the interaction of the Empire's classes of peasant and samurai. Chapter 4 is about Rokugani religion, shrines and magic. Chapter 5 covers the teachings of Shinsei, the lives of monks and priests, and the role of temples and monasteries. Chapter 6 is about the wild lands, the mines and logging villages and other rural areas. Chapter 7 is new mechanics - the Imperial Family's schools, playable kitsune shapeshifters, playable Kolat agents and new titles, mainly.

But first, let's talk about the history. It is presented as a text written by Imperial Scribe and historian Miya Chinatsu, and it is explicitly the official Imperial History, which is written expressly from a Rokugani perspective and almost certainly does not line up with the histories kept by, say, the Yobanjin, foreigners or even secret groups within the Empire itself. But hey, let's see what the timeline is now.

In the beginning, there was Nothing. Nothing is not even Void, because the Void does not change and cannot change. The Nothing, however, eventually realized it was alone, and in realizing it, the Nothing became afraid, which made one third of the world. Then, it longed for companionship, and in so doing, it made the second third. At last, it realized what it had done, regretting its fear and longing, and so created the final third. When this was done, the Nothing was no more, because the world had taken its place. Of course, in that time it had neither form nor solidity, being like a dark fluid swirling in chaos. Eventually, the lighter parts separated out, becoming hte Heavens, while the heavier parts became the earth. From this came the Three Nameless Gods, who saw that while Heaven and earth formed, all within was as yet wild and unshaped. They discussed, and they made two gods, sent forth to give shape to the world. These gods thought of how this could be done, and they bowed, kissed the earth and named it.

From this came life - new gods, new beasts. Suijin, lord of the oceans. Kaze-no-Kami, the god of wind. The Four Cardinal Winds, the Elemental Dragons. More. The two gods also gained names - the man Onnotangu, who was the moon, and the woman Amaterasu, who was the sun. They were attended by the shizoku, the tribe of gods, and below them the mazoku, the underworld demons, toiled to oversee what few dead souls existed. At this time, no humans existed. Instead, there were the Five Ancient Races - the tengu, the kitsu, the ningyo, the trolls and the zokujin. Little is known of such ancient times, of course. While the last of the Kitsu married into the Lion Clan, if he gave them any histories of his people the Lion have not shared them. What is known is primarily stories recorded by the granddaughter of Tsumaru, the ningyo wife of the Kami Shiba. The Unicorns claim that after the Five Ancient Races came another race, snakelike, which dwelled in the lands that would become Rokugan, based on the existence of statues within the Shinomen Forest that resemble snakes with human features. However, nothing is known of the truth of this.

As time passed, Onnotangu and Amaterasu had nine children, the Kami. As they grew, Onnotangu saw their strength, empowered by both his own blood and that of Amaterasu, and began to fear that they would one day usurp him. He became envious and fearful, and decided he would prevent this by devouring his own children. Amaterasu wept over this, her tears falling to the earth to form salty pools. However, she would not fight her husband directly, so she found a different solution. Each time Onnotangu swallowed a child, she would give him a cup of sake containing a single drop of poison. By the time he reached the youngest child, Hantei, he was so addled by the poison that Amaterasu was able to swap the child for a stone. At last, Onnotangu was satisfied and went to sleep. Amaterasu smuggled Hantei out, hiding him and teaching him of honor and war and strength. When he had learned all he could, she gave him a sword of starlight and sent him to rescue his brothers and sisters. Onnotangu was barely awakening when Hantei arrived, and the two began to fight. The duel was long, and Hantei was able to avoid his father's blows while striking his own heavily. Onnotangu's blood fell to the earth, landing in the pools of tears Amaterasu had wept. From each pool emerged two humans, and humanity is born of the Sun's tears and the Moon's blood. At last, Hantei found a chance, carving open Onnotangu's stomach and freeing his siblings. The last of them, Fu Leng, was caught by his father as he fell, but Hantei cut off his father's own hand, causing Fu Leng to fall to earth as had all the others. Fu Leng grabbed Hantei in a panic as he fell, and so all the Kami tumbled from the Heavens.

However, Fu Leng landed far from the others - Hantei, Akodo, Doji, Hida, Togashi, Shinjo and the twins Shiba and Bayushi. None knew where he fell. Having landed on earth, the Kami were shocked to find that they had become mortal, able to die. But even more, they were amazed by humanity, which was pitiable and weak despite the nature of its birth. In this dawning age, humans lived in scattered tribes, like the Yobanjin do, and worshipped the Fortunes, who are the gods of human labor. They lived in tiny villages and small towns, making crude pots and bronze weapons. They were barely able to farm wild grains or beans, and wore uncured hide and woven grass. However, they had no letters, no art, no dye. They relied on word of mouth and wild drums. Raiding was common, without strategy or honor.

The Kami decided that each of them would travel the land and judge it. Because all eight of the Kami were beautiful and wise and strong, they always gained attention where they went, and soon each had many followers seeking to learn from them. The Kami taught the arts of writing, calligraphy, smithing, making instruments and more. They taught honor and loyalty. (Some say a tenth Kami existed, called Ryoshun, but he died in the stomach of Onnotangu, and many claim he fell to the Underworld, where he serves or helps the Fortune of Death. Others say this is blasphemy, worthy of death.) In the year recorded as 5 Imperial Calendar, the Kami returned to the place they had fallen, deciding that humans had great worth, and so must be organized and governed, to bring wisdom. Thus, they would hold a tournament to see who would lead. Of the Kami, Togashi refused to participate, for it is said that with his immense wisdom, he saw that Hantei would inevitably win, and saw no point. (Hantei did, indeed, win.) Naming Hantei Emperor, the Kami then set about to forge an empire. All of them but Hantei formed clans made of their followers, and Hantei granted land to each, where the Kami settled and taught the ways of Bushido, teaching many warriors to make the land safe, and to fight those foolish humans who did not understand the blessings of the Kami and resisted their rule. Others learned the arts and craftwork, especially those that served Doji, and made many things of beauty. Towns grew to cities, roads were made, and the Emperor chose as his home the very hill upon which the Kami had fallen, which is now the site of the capital, Otosan Uchi.

Next time: Fu Leng returns.

The War At Daddy's House

Original SA post Emerald Empire: The War At Daddy's HouseIn 39 IC, Fu Leng returned from the south. Hantei's rule had been wise and beloved, with perfect laws and perfect rule. The other Kami were overjoyed when Fu Leng returned...but cautious, because the Crab had reported evil stirring in the south, where he came from. Fu Leng was enraged that his siblings had excluded him from the tournament to decide the emperor, though their reason had been that they thought him dead. He called them liars, traitors and monsters, and it soon became clear that he had been corrupted by the evil power of Jigoku, the dark mirror of the true underworld. He demanded the right to challenge Hantei for rule of Rokugan - which Hantei accepted, naming Togashi as his champion. However, when Fu Leng told Togashi to name his weapon, the mighty ruler of the Dragon Clan named all of Rokugan and all that lived within it. Infuriated, Fu Leng retreated to the Shadowlands, vowing he'd return with his own army to fight that duel. The south was overrun by creatures of darkness - goblins, oni and worse. Warriors gathered to face these monsters, but all were defeated. Fu Leng used his evil magic to summon new forces and win battles, and the armies of Rokugan were slowly pushed back.

In this time, the tribe of Isawa joined the Empire. Before then, the spiritual leader Isawa, who was beloved by the Fortunes and lesser kami, had seen no prupose in serving under the Kami, but as the war went on, Shiba himself went to the Isawa tribe and begged their aid. Isawa refused, for he would not give up his tribe's traditions - and so Shiba knelt, swearing that he and all his descendants would serve Isawa and the Isawa tribe, should they agree to join the Phoenix Clan. Isawa was so impressed that he accepted, and to this day, while a Shiba is Phoenix Champion, the clan is run by the Isawa. It was also in this time that an old monk came to the camp of Hantei. He named himself Shinsei, and he said he knew how Fu Leng's forces might be defeated. While at first, Hantei would not listen, after Shinsei managed to defeat the guards sent to get rid of him despite wielding no weapons at all, the Emperor grew curious. The two spoke into the night, and Shiba recorded all that was said. This became the Tao of Shinsei, the entire teachings of the Little Teacher about the world, the elements and enlightenment. Shinsei said that fortune favored mortals, and so he would gather seven human warriors to defeat Fu Leng. Hantei gave permission, and one warrior from each tribe was chosen. These were the Seven Thunders.

The Seven Thunders headed south, and for many weeks, no one know anything of what they did. However, one day, the armies of the Dark Kami suddenly fell to pieces, and the warriors of the Empire were able to defeat them in a fierce battle, driving them from the battlefield. Thus it was clear that the Day of Thunder had come, that the Thunders had won. Hantei had a feast prepared, but of the Thunders, only two returned - Shinsei, and the Scorpion Thunder Shosuro. She carried twelve scrolls which she said bound Fu Leng, and Hantei ordered that these were to never be opened, giving them to the Scorpion for safekeeping. That is the end of ancient history, such as it is, and the beginning of the era known as the Thousand Years of Peace, in 42 IC.

With Fu Leng defeated, the Rokugani returned to building up the Empire. However, Hantei did not forget what had happened - an enemy from without had come, after all - and called his sister Shinjo, for she had always been a wanderer. He charged her and her clan, the Ki-Rin, to explore outside the Empire, to see what threats lay without. Doji was sad to see her sister go, giving Shinjo a beautiful fan she had personally made, to remind her sister of their close bond. Shortly after Shinjo left, Hantei died. Some say he died of a lingering wound from the war with Fu Leng, while others say he merely tired of the mortal realm and returned to the Heavens. He was succeeded by his son, Hantei Genji, the Shining Prince. Genji had, in his youth, been a great adventurer, and as Emperor he sponsored many temples and monasteries, to spread the knowledge of the Tao of Shinsei and the Five Elements. He also continued the work of infrastructure until his death, when his daughter, Hantei Murasaki, took the throne.

It was during Genji's reign that the Imperial Law was codified and reformed by Doji Hatsuo and Soshi Saibankan. Under Hantei, the law had always been perfectly just and without omission, for he was a Kami, but judges were mortal and flawed, varying in ability. By annotating the law, Hatsuo and Saibankan allowed for consistent rulings across the Empire. They founded the Emeral Magistrates, officials with authority to investigate crime and pass judgement. The land prospered for many years, producing far more yield than ever before, with the spread of cheaper and more effective iron tools and the discovery of wheat flour noodles, which could be made in lands too cold or dry for rice, and which were easier to cook than whole grain while being tastier than porridge. Trade spread, but barter soon became limiting. Many areas used plates or bars of gold and jade, but they were hard to use due to varying size and forgery. Coins developed with the rise of mining and casting, and the Emperor decreed their value - the koku would be set at the worth of an amount of rice sufficient to feed one person for one year. This and smaller coins allowed for easy and profitable trade.

Literacy also spread widely among the samurai class, for many clans prized ideas and wisdom. Annotated maps and written orders were useful to armies, reports preserved knowledge, and written works spread. The famous books Leadershi (by the Kami Akodo), The Sword (by the first Emerald Champion and husband to Doji, Kakita), Niten (by Kakita's great rival, Mirumoto Hojatsu), the Tao of Shinsei, and Elements (by Isawa). By the end of the first century, Lies also appeared, generally attributed to the Kami Bayushi. Even more books spread over the years, and the people achieved great advances in astrology, philosophy and theology. They unified the teachings of Shinsei and the ancient worship of the Fortunes, developing new healing methods and use of alchemy. The tea ceremony spread, invented by Lady Doji, and became quie popular.

In 390 IC, however, came the Time of Greed. Disputes between the Crane and Crab over land were common. The Yasuki family renounced their loyalty to the Crane, joining the Crab, and there was no rule in the Empire. While a Hantei sat upon the throne, the Crane, Phoenix and Scorpion Champions had conspired against him. They formed the Gozoku, a conspiracy that kidnapped the Emperor's heir, forcing him to make political concessions, and when the Emperor died, they prepared to make that heir their puppet. However, while the Emperor's sons had all been fostered to be subservient to the Gozoku, the youngest child, Yugozohime, had instead been raised by the Lion. She was a mighty warrior and an honorable samurai. When her father died, she challenged her eldest brother to a duel, slaying him and claiming the Throne for herself, ending the power of the Gozoku in 435 IC. The decade that followed would be known as the Blooming of the Lotus.

Next time: Gaijin appear.

Brothers in Shinsei

Original SA post Emerald Empire: Brothers in ShinseiBy the 400s, the monks known as the Brotherhood of Shinsei were leading innovators in medicine, and many commoners and nobles supported them as a result. Their growing resources and respect led many to the Tao and its teachings, but few peasants actually knew the Tao rather than just stories about Shinsei. The Brotherhood began to sponsor festivals that performed plays based on events of the life of Shinsei, mixed with sermons and readings from the Tao. This led to the development of kabuki theatre, quickly a favorite among wealthy heimin and lower ranking samurai. As the writers got better, even ranking samurai began to accept it. The monks also spread the tea ceremony to all classes, even the geisha. Some samurai found this scandalous, but many priests argued that teaching the sacred ceremony was not harmful and would help cleanse the spirit of interaction with money. Today, geisha, wealthy artisans and merchants are the most common peasants to know the ceremony, as few farmers have much interest, though historically there have been major tea masters from among the peasant classes.

This was also the time in which foreigners first arrived in Rokugan, seeking audience with the Emperor Yugozohime. Before now, the only gaijin known to Rokugan had been the desert tribes in the west and merchants from the Ivory Kingdoms. These gaijin came from a distant land called Pavarre, a kingdom across the great Sea of Amaterasu, looking for trade. Yugozohime allowed them to remain for two years to see if they could learn to be civilized, bringing much fear and debate from courtiers and leaders. The minor Mantis clan were especially active in support of this, seeing a chance to grow powerful and rich, while others were put off by their strange and ignorant ways. After the two years, the Emperor decided she had grown tired of the gaijin, commanding them to cease all trade with Rokugan and to leave immediately. In response, the gaijin took up arms against the Empire; this doesn't count as war, we are told, because gaijin aren't people. They slew the Emperor herself, and as a result all gaijin in Rokugan were put to death in what has become known as the Battle of the White Stag due to the cliffs at which the fight took place. A few escaped in ships, but were confronted by Crane and Mantis fleets. If any got past that, they have not returned.

It is theorized that the gaijin brought about spiritual imbalance, which allowed a maho-tsukai, a user of forbidden blood magic, to grow in power. His name was Iuchiban, and he was first known in the beginning of the 500s, when the artisan Asahina Yajinden made several swords for the Crab, Crane, Lion and Scorpion. Shortly after, the Lion Champion attacked the Dragon in midwinter, the Crab Champion murdered his children and the Crane Champion confessed to an affair in front of his entire court. All three killed themselves with the gifted blades. Only the Scorpion Champion escaped, revealing the corruption of the smith and his membership in the Bloodspeaker Cult, led by Iuchiban, whose history is unknown. He led an undead army on the capital, for in that time bodies were buried rather than burned, but he was defeated due to the timely warning of the Scorpion. After Iuchiban's execution, he was buried in a tomb meant to prevent his spirit ever escaping, and he was the last human ever buried in the Empire, for after that the Emperor decreed that all corpses must be burned to prevent their desecration by evil magic.

After his defeat, the revival of the older No style of theater became popular, due to a number of plays written by Kakita Iwane about the lives of the Kami, giving a chance to return to a past more glorious than the recent tragedies. No became very popular among the nobles, though not the peasantry, due to its wide range of emotion portrayed with minimal action. Woodblock printing also became popular to spread prints of famous actors and characters, though samurai derided these as perversions of true art, without real soul. (Besides, actors are mere hinin, making it even worse.) The end of the century brought the reign and death of Hantei the Sixteenth, the only Emperor known to have lost the Mandate of Heaven, ever. He is remembered as the Steel Chrysanthemum, whose early years were promising before his descent into paranoia and violence. He executed thousands for crimes that never happened, and at last, after he ordered his own mother strangled to death before the Court, his son rebelled and led the Imperial Guard against him. The son's success is proof that Amaterasu had withdrawn her support. Hantei XVI's son then retired to the Brotherhood of Shinsei, and all of the guards involved in the revolt committed seppuku. The STeel Chrysanthemum's youngest brother took power, reigning well and in peace for a long time.

After centuries undisturbed by the Shadowland forces that had followed Fu Leng, most had forgotten the threat, outside of Crab lands. They were merely a historic thing, and it is believed that the reemergence of the Shadowlands and Iuchiban in the 700s was divine punishment, either for the Steel Chrysanthemum's actions or the blasphemy of his own guards striking him down. Still, not all was bad. Agasha Hyoutaru developed a new, more vibrant ceramic glaze, and Kaiu Naizen invented a new kiln flue to allow greater control of pot firing, which led to a boom in decorative ceramics. Still, the Shadowlands invaded twice in the 700s. In one event, a massive attack distracted the crane, allowing the Kinjiro no Oni to lead a second force to overwhelm a Crane garrison near Earthquake Fish Bay until the arrival of Daidoji Masashiga, daimyo of the Daidoji, who drew the forces of the Shadowlands into the bay at low tide, keeping them there until high tide destroyed both forces. Thus did the Daidoji earn the nickname Iron Crane, granted by the Crab survivors in honor of Masashigi's sacrifice.

The next year, the oni known now only as the Maw swept across the Crab lands, pushing so far north that the ancestral fortress of the Hiruma, Daylight Castle, was lost entirely. While the Hiruma and Hida, aided by the Kuni Purifiers and Witch Hunters, were able to stop the advance, the borders shifted. The Kaiu built the Carpenter Wall, which still stands even now as the defense against the Shadowlands. The Hiruma lands have never been recovered, the first territorial loss ever to strike the Empire. This was not even the worst, however, for in 750 IC, the spirit of Iuchiban escaped his tomb, possessing a body to replace the dead one it had lost. Iuchiban gathered an army of cultists and undead, attacking once more. He was stopped at the Battle of Sleeping River, where a Togashi Order monk trapped the sorcerer's spirit in his own body long enough for both to be sealed away. In the aftermath, it was found that many had defied the Imperial edict against human burial, and hundreds were harshly punished.

In 815, the Ki-Rin returned to Rokugan, and for the first time, the Great Clans nearly went to war with one another. Gaijin goods, unseen since the expulsion of the gaijin centuries before, poured into the Empire. Some wonder if this is the cause of the elemental imbalances of more recent centuries that led to earthquakes in 1120. Due to various magical happenings, the Ki-Rin returned through the northern Shadowlands, and in their haste to escape the wastelands, they actually used their cavalry tro force their way through crab defenses, and were not at first recognized. In their wanderings, they had changed their name to Unicorn and had taken bizarre clothing and customs, even losing the purity of their classical language. Their horses were amazing, however, and their tactics had never been seen before, allowing them to defeat Scorpion armies that came after them. As they forced their way through the mountains, the Lion moved to stop them, but were halted by winter snows. This allowed the Unicorn to make contact with the Crane, who recognized Lady Doji's fan, gifted to Shinjo. The Emperor forbade the Lion from attacking, giving the Unicorn their ancestral lands - which the Lion didn't appreciate, as they'd been given stewardship over the fertile farms of the Ki-Rin. However, they obeyed. Many saw the Unicorn as gaijin, despite the Crane testimonies, due to their strange names, manners and food - especially because the Crane had adopted the Moto family, who were kin to the Ujik of the west. Some argued that the Moto should be expelled as gaijin, but the Unicorn Champion appealed to the Emperor, saying that the Moto had been adopted by Shinjo's own command, and the Emperor agreed.

The Crane set about civilizing the Unicorn - as best they could, anyway. The Unicorn accepted much, but would not give up their foreign names, food, clothing or the custom of shaking hands. While Unicorn courtiers behave properly outside their own lands, the Unicorn territory is foreign still to most Rokugani. However, they also brought innovations in metalwork, leatherwork and dying of fabric, as well as, of course, horses, advanced riding techniques and stirrups. They also were quite wealthy due to trade with the nations they'd met outside the Empire, and possessed the unique name magic of meishodo, by which they bound spirits into talismans, allowing similar magic to the shugenja of other clans without needing to bessech the kami in the same way. Many still see this as blasphemy.

Next time: Opium.

Accidental Drug War

Original SA post Emerald Empire: Accidental Drug WarOne of the herbs that the Unicorn brought back with them to Rokugan was the opium poppy, used to produce the opium drug. The Unicorn used it as a painkiller, and it quickly spread across the Empire - including as a recreational drug, one which reduced devotion and loyalty. This led to public outcry even as the Yogo family discovered that it grew excellently around the lands of Ryoko Oawari Toshi, and so the Scorpion Champion convinced the Emperor to make the growth and use of opium poppies regulated, and to give the Scorpion sole right over growing and making opium. Over ten years, the City of Lies grew massively with the opium trade, and while the Scorpion control of medical opium made them rich, it didn't stop much misuse of opium, especially as the Kitsuki discovered that the land used for opium poppies far exceeded the amount needed to supply legitimate opium. However, the local governor assured the Empire that it was simply to ensure a high quality supply, and that all low quality opium was destroyed. This is certainly and surely true, not to be questioned.

In the 900s and 1000s, urban areas expanded massively, in large part due to the innovations brought by the Unicorn, as well as improved agricultural techniques and greater crop yields which allowed taxes to be paid without need for so many workers, sending many youths to the cities. For some traditionalists, the rising mobility of peasant merchants is an offense against the Celestial Order, of course, but it is improper to speak of such things. The Lion, especially, were not happy with the changes, punishing peasants harshly if they tried to abandon their villages or sell their produce rather than giving it unto the lord as tradition mandates. Even now, the Unicorn city of Khanbulak represents a symbol of outsider influence in Rokugan, and has encouraged the Mantis to trade in gaijin goods. The official acceptance of the Unicorn has been taken as a tacit approval of the practices they brought, and so gaijin goods and even travelers have been slowly met with more acceptance - slowly being the operative word. Several ports grew massively in this period.

In the late 1000s, a monk from the Shrine of the Seven Thunders described a new and controversial doctrine that has formed the Perfect Land Sect. This monk was Yuzue, who believed that the conversation between Shinsei and Hantei had started an Age of Celestial Virtue that lasted eight centuries - one for each Kami that heard Shinsei's teachings - and that the ninth began an Age of Declining Virtue, full of corruption and problems following the Tao. To get Shinsei to return, Yuzue would endlessly chant a special mantra proclaiming total trust in the Little Teacher, and believed that if enough people chanted it sincerely, Shinsei would return. Yuzue's student, Gatai, founded the Perfect Land Sect shortly after her death. Gatai's work claimed that Shinsei did not return to the Void when he left Ningen-do, but instead lived in a Perfect Land in the Celestial Heavens of Tengoku. The sect now believes that those who chant the kie, Yuzue's mantra, can join Shinsei in the Perfect Land after death rather than facing the wheel of karmic rebirth. In the Perfect Land, they may study under Shinsei himself, achieving enlightenment without need for suffering. For many Shinseists, the Perfect Land is heresy, a defiance of the Tao and the Celestial Order. However, they are very popular with peasants, as they offer the chance at freedom from mortal trials and the suffering of rebirth. Many heimin believe the Age of Declining Virtue refers to corruption among hte samurai class, which has further led samurai to denounce the Pure Land Sect. By the mid 900s, the sect was illegal in Phoenix Lands, forced to seek refuge among the mountains of the Dragon.

The Unicorn innovaitons also sparked new progress in the fields of the arts, which had fallen to stagnancy in the late 700s, during which only one work, the journal of the duelist Ikoma Hanzo, titled The Days of Salt and Sun, had any literary value. We get a brief aside about why this book owns and you should read it from Miya Chinatsu. However, in the 800s, artists were forced to confront the Unicorn ideas and either accept or reject them, looking upon the world as new once more. Painting and novels thrived, as did poetic competition. For one thousand years, the Empire has been at peace, with no wars - only peasant grumbling, Shadowlands infestations and purges of gaijin. No war, do you hear me?

This brings us out of the timeline and into chapter one with a discussion of feudal governance. The feudal lords, down to the lowest regional daimyo, are based out of castles, both for reasons of symbolic power and because they serve as administrative centers. All taxes are brought to the local castle, and soldiers and magistrates operate out of them. Commoners that require a lord's aid must petition them at the local castle. Each Great Clan divides their territory into several provinces, each with a daimyo based in, generally, the strongest of the provincial castles. The Clan's champion and family heads may also use the best of these, or may maintain their own seperate castles. Each of these ranking lords officially rules a province, but generally delegate the job to a seneschal or hatamoto. Major cities also have governors, who usually live in a nearby castle, though not always - some prefer unfortified homes within the city itself. Still, a city or provincial governor has ruling authority over their lands, including the maintenance of law and order and the collection of tax.

Below the governors are the lesser lords, or shugo, who rule over chunks of the territory in the name of their governor. These are the lowest ranking daimyo, often ambitious and prone to fighting with neighbors over territory. Each of them, of course, has their own castle - without one, they would lose much face. As a result, there are hundreds of castles across the Empire. While a lesser lord may only role over a very small region, maybe even just one village, they are landed gentry with the right to collect tax, and stand higher in the social order than a border-guard samurai or member of the armies. However, such small lords are not daimyo and are far too weak to have castles, instead living in less fortified manors.

Rokugani castles date back to the earliest days of the Empire - indeed, the Isawa histories claim that the Isawa tribe built them before even the Kami fell from the Heavens. As a result, the traditions of design and construction are ancient, using styles based on those developed when Hantei founded Otosan Uchi and set forth the "correct" methods of building, expounding on the ideas of architecture and engineering. Typically, these design elements are considered to comprise of a sloped tile roof and wall-top, a vertical and pagoda-like structure for towers and keeps, and plastered, smooth and lightly sloped outer walls. Because Hantei's palace keep was ten stories high, no keep in the Empire is more than nine stories, lest its master be accused of placing themselves on a level with the Emperor. Castles serve as a center of power, to be sure, but they are also a symbol of needs, values and power for the clan. While all share the same basic design principles, they are each modified to reflect a clan's needs and aesthetics. Crab castles are practical, Lion castles austere and hightly traditional, Crane castles beautiful, and Scorpion castles full of hidden passages. Specific families and even individual lords also alter the designs based on their duties and beliefs, which may well diverge from the general tenor of the clan. For example, the Daidoju and Kakita family castles are extremely different, despite both being Crane designs.

The Unicorn castles, as you might expect, are significantly less conventional than those of other clans. Because the Unicorn were gone for eight centuries, they found many foreign influences in their travels. Their architecture merges these ideas with the classical designs of the early Empire, and only have gradually begun to adopt more modern standards. Far Traveler Castle, for example, is a huge three-sided keep, while Battle Maiden Castle has bell-shaped tower domes, and the Moto palace at Khanbulak isn't even a single solid structure, just a series of immense and beautiful tapestries hung between massive columns. Only one major Unicorn castle conforms to Imperial expectations - Great Day Castle, built for the specific purpose of good diplomacy with the other Clans.

Next time: What a lord is actually expected to do.

How 2 Feudal Lord

Original SA post Emerald Empire: How 2 Feudal LordThe main job any lord has in Rokugan is to maintain order. This means protecting their lands from threats - invasion, bandits, pirates, rebellions - and collecting taxes. To do so, they keep a force of jizamurai who serve as their garrison, patrollers and protectors. The more powerful and wealthy a lord, the more jizamurai they can maintain and the more secure their land, as they must keep the jizamurai properly armed and armored out of their own pockets. Lords will also appoint various lower-ranking officials, like tax assessors, magistrates and local landholders to maintain law in smaller portions of their land. In the case of war, a lord is also responsible for raising, training and arming the ashigaru peasant-soldiers used in battle. Any poorly defended or lawless land is the fault of its lord, who must fix the problem. Failure to do so is usually punished with public shaming or even demotion in rank - or, in the worst cases, seppuku. Lords must also maintain the welfare of their vassals, though the level of care varies by family and clan. Some will go out of their way to ensure all vassals live well even to the point of ensuring good marriages or giving gifts at any major event, while others only pay a monthly stipend and nothing more. Most are somewhere in betwene.

Due to its defensibility and centrality, a lord's castle is usually where all governance happens. Taxes arrive there each fall and are held securely until the proper shares are sent on to the Emperor, bandits are brought there for execution or the display of their heads as a warning, wars are planned and diplomats are hosted there. The duty of hospitality is vital to being a lord, who must provide safe and good housing to any visiting samurai guest, no matter their rank. Of course, what passes for hospitality varies by clan - Crab or Lion lords are usually just going to give you a room and some food, while a Crane will more likely go out of their way to make you comfortable and entertained. Likewise, clans vary on how important it is for a castle to serve as a center of culture, with more martial clans tending to minimize this job at best.

Lords must also coordinate and host religious festivals over the course of the year, working with local temples and shugenja to ensure observances are carried out properly and auspiciously. The Rokugani are a pious and extremely superstitious people, especially commoners, and lords that fail to venerate the kami and Fortunes or whose rule is plagued by evil omens will often face internal discontent. This is a problem because a lord's final duty is to keep order among the heimin and hinin, the peasantry. A lord that allows disrespect or lawlessness among the peasants or who fails to protect them from danger is failing in their duties, and may face a humiliating peasant revolt. In such a case, the castle is effectively a prison in which the lord and their vassals become trapped by the angry peasants.

All castles share a single decoration - anything else is variable. That decoration is the banner in the court chamber, which displays the symbols of the lord's clan and family on the wall above the dais, as well as any personal mon the lord may have. If guests of rank are visiting, their banners are hung across the chamber from this banner as a show of respect, though sometimes in ways that give subtle insult, such as ensuring they are slightly lower than the lord's or being put on a side wall instead of directly opposite. When hosting the Imperial Winter Court, the hanging of banners follows elaborate rules of etiquette. Tradition dictates that the Imperial banner with the chrysanthemum symbol of the Hantei is largest and hangs directly over the dais, flanked by the banners of the Seppun and Otomo, with the banners of the Great Clans hung on the side walls in an order based on the current placements in Imperial favor - traditionally, the Crane and Lion are closest to the Emperor, but if the Emperor is mad at them this may not be the case. Traditionally the Dragon are placed on the wall directly opposite the Emperor's banner, in honor of Togashi's refusal to participate in the Tournament of the Kami.

The court chamber is included, of course, in any castle that's more than just an outpost, even if it's small. This is where court is held, and court is where a lord listens to their samurai for discussion and advice, as well as pleasant conversation and diplomacy. By tradition, a court chamber is a two-story room with a balcony around the second floor level. The main room is largely unfurnished, but for a dais on one end, where the lord or their deputy sits. The upper level usually has some tables. Courtiers and diplomats use both levels to form various conversational groups, and any artistic performances or formal presentations are done in front of the dais. Ideally, a court chamber has room for 200 samurai on the main floor, but only a handful of castles actually manage that. More commonly, even both floors together can't handle that many, and additional rooms are used for large events, or they are held outdoors in gardens or the parade ground. Court is open during the day to visitors, but the lord is usually only present for the morning. Guests may ask permission to address the entire court, especially to announce important events such as marriages, formal alliances or declarations of war. This will usually happen before the dais, with the speaker addressing the lord but heard by all. Artistic performances may happen at any time in the day or evening, but outside of formal court hours they are often held elsewhere in the castle. When court is not in session, shoji screens are often used to subdivide the hall for other uses, such as to provide extra space for barracks or an infirmary in time of war.

The arts performed at court vary wildly by castle. Some lords like musicians on the balconies, while others display bonsai trees, shoji-screen paintings or ikebana flower arrangements. Jesters may be called in to reduce tension by humor or to goad visitors from rival courts. Wealthy or ambitious lords might even arrange for indoor koi ponds or plays, while poor or ascetic lords may minimize decoration, often with comments about Shinsei's teachings about worldly distractions. Jesters in Rokugan are unusual artisans, not like what we might think of from the word. They are masters of various artistic forms, including kabuki, dance, song and poetry, and they often are keen students of politics. Their job is simple: expose the hypocrisies and pretensions around them. They are a socially acceptable exception to the typical Rokugani rules of etiquette which dictate ignoring spectacles and being silent, being allowed to call out what others must endure. The idea apparently originates with the Crane, probably in the second or third century. Jesters are samurai, but need not be from any specific school or training - they just need to show skill with the job and be appointed to it. Acting as a jester without a lord's appointment and official protection is a good way to be disgraced or killed. A Rokugani jester is neither madcap nor cheerful, but typically sardonic, sour and biting. They often use double intendres, puns and riddles to make their points, drawing attention to dishonor and satirizing the careful and polite conversations around them. So long as they use this mockery, they may call out the behavior of others without much risk of a duel. Of course, they can only go so far - a Lion or Crab samurai is unlikely to put up with constant needling from a jester for too long, after all, and the wise jester learns when it's best to retarget.

Every castle also maintains a sizable population that is effectively invisible to the entirety of the samurai within - the servants that keep it clean, orderly and working. Servants never use the main doors, relying on special ones that are typically ignored and unnoticed by the samurai. In some ways, this gives them quite a lot of freedom - a samurai is restricted in where they may go in a castle by rank, with most being barred from places like the lord's personal chambers. Servants can go everywhere and no one cares. They see and hear just about everything that goes on. Samurai may be good at keeping secrets from each other, but they barely notice the servants at the best of times. However, this sort of social blindness also means that samurai rarely actually exploit that fact, either. Talking to a servant for any reason but to give orders is highly demeaning. That small group of samurai that are willing to lower themselves to do so, however, gain a significant advantage politically. Simple bribery, threats or blackmail, or even just charisma, can gain much useful information from servants, and servants' entrances are extremely useful if you want to get in and out without notice, for who would dream of a samurai using them? The Scorpion tend to be the most common of samurai that actually are willing to do this, though even they are not universally so.

Next time: Seven People You Meet At Court

Court Tiers

Original SA post Emerald Empire: Court TiersCourts are dominated by the minority of samurai known as courtiers, trained and specialized in politics. There are relatively few of them compared to the warrior samurai, and they overwhelmingly are part of the courts. There are many, many ranks within a court, but a few are more important or universal than others. Ambassadors are empowered to speak on behalf of a lord and make binding agreements. Not all diplomats are ambassadors, who have additional prestige, and the job is extremely demanding. If an ambassador fucks up or shows weakness, that reflects on their lord and clan. This is one reason why courtiers are so frequently found using veiled and indirect language. Speaking bluntly is rude or indelicate, sure, but for an ambassador it's outright dangerous - if they speak too clearly, they end up committing themselves unwisely, and because a samurai's word is their bond, that is as binding as a written treaty. Indirectness gives room to maneuver and withdraw as necessary without loss of face.

Karo, or seneschals, are those samurai assigned as senior aides to their lord. They can be advisors, but their real job is to manage their lord's affairs and serve as the castle's chief administrator and recordkeeper. Further, they are the lord's stand-in when the lord is away. Being named a karo is a huge honor and a show of significant trust, and the office is often hereditary. When possible, a karo will be a hatamoto as well, to ensure total loyalty. A hatamoto is a lord's personal vassal, and only the most senior lords, typically family daimyos or clan champions, may name them. Their loyalty is not to the office of lord but to the actual person, with no intervening distractions, after all. Socially, a clan champion's hatamoto outranks a provincial lord, as well, so they are often used as troubleshooters to deal with disloyal or problematic provinces.

Artisans are those samurai that focus on artistic pursuits by specific training rather than as a hobby to supplement more martial training. They typically operate within the court system because it's the best way for them to show off their work, as a form of entertainment for the court. Most lords that care about having a civilized court will attempt to attract at least one or two artisans to the castle and to get more prominent ones to visit and exhibit their works. Nakodo, or matchmakers, are used by samurai families to help arrange advantageous marriages. Nearly all samurai marriages are arranged, and a skilled nakodo is highly in demand. Any lord of real note will have a nakodo at court, and their services are a useful diplomatic bargaining chip. When not serving as matchmakers, nakodo are typically found doing the same work as any courtier.

Sensei, instructors, are the last common position found in most courts. Every castle has at least one training dojo, after all, and a large castle may have several. The most prestigious schools with the best sensei are always in major castles of a clan, so they are centers of learning as well. Even a minor castle will maintain a small dojo and a sensei to train the bushi, and sensei often also serve as advisors to their lord, especially if the lord was one of their students. Their words are always given considerable influence, for as trainers they are responsible for ancient school secrets.

We then get a description of what a routine day in the life of various castle inhabitants would be like. It is, as many things in Rokugan are, pretty formalized and standardized by tradition, but gives a surprising amount of free time, especially around the afternoon or evenings. We get another way a lord can insult their guests - if a lord is armed or armored when meeting them, it is a show of distrust, while a lack of even symbolic guards is a show of trust. Lords often offer 'sword polishing' services to guests, as being asked to leave your sword behind, while a legitimate request, is often seen as insulting, so leaving them with a sword polisher is a way to save face. Guests have very strong rights under the Rokugani rules of hospitality, and so even if you are in the midst of a blood feud, it is expected that a guest will be safe in your castle, to the extent that they can expect to leave their sword in their room unless they're a yojimbo. Further, it is forbidden to openly harass and mistreat guests, which is one more reason for the court's development of the art of the subtle insult - it can be done without violating a guest's rights. Crude insults or physical attacks are not only offensive but dishonorable and worthy of punishment. Guests, however, are also bound - they must not freely insult others nor disrupt the harmony of court, at risk of dishonor and possibly a duel or even expulsion from the castle.

Castles are one of the few types of building in Rokugan to make heavy use of stone in their construction, especially in the outer walls and foundations. Wood is typically used for the upper levels and interior, but the amount of wood to stone varies by local tradition and resources. The Crab make heavy use of stone, both in their massive castles and the Kaiu Wall, and the Lion use stone whenever possible to increase defensibility, while the Dragon do so because stone is much more common than wood in the mountains. The Unicorn, despite their martial bent, make very little use of stone due to their nomadic traditions and the large number of forests in their territory. Other clans use relatively little stone as well, finding wood easier to work with, and the Crane and Phoenix in particular tend to view their castles more as art pieces than martial fortresses.

Castles are usually placed along important routes of travel, like roads, mountain passes or rivers. Ideally they occupy an elevated position on a mountain or hilltop. If there is no available hill, they should at least be in an open area in which attackers cannot use the terrain for shelter. A castle built on a mountain is known as a yamajiro, a hilltop castle is a hirayamajiro, and the most common type, the castle on open ground, is a hirajiro. A castle will be designed by a single clan artisan with their own unique style, and often the artisan for a new castle is selected via competition. Each architect will be backed by a different patron, seeking power and rank in their clan by sponsoring the winner. Deciding on which architects to allow to compete may require weeks of secret negotiations and political maneuvering, and the sponsors and architects will also present gifts to the lords. In theory this is to demonstrate seriousness and dedication; in practice, it's bribery. This is not, however, a universal practice. The Crab and Lion rarely allow politics to play any part in a castle's construction - the new castle is simply too tactically important. The manner in which plans and designs are presented varies by clan, as well, and may be public or private. Crab architects are known for use of highly accurate scale models, while the Crane prefer artistic drawings, and the Scorpion discuss secret and delicate aspects of design with the lord in private. The actual work of construction is done by peasant labor conscripted from the locals. The architect and samurai artisans will oversee the work and select skilled tradespeople as assistants. The Crab are known to actually put heimin craftworkers in charge of some portions of the labor, which is viewed as highly pragmatic and distasteful. The Scorpion, on the other hand, often rely on the labor of condemned criminals, and many rumors claim that a large portion of such labor is buried in castle foundations.

All castles are known either as a shiro, or castle, or a kyuden, or palace. The distinction is, in theory, that a kyuden is capable of hosting the Imperial Winter Court. By tradition dating back to the first century, the Emperor never remains in Otosan Uchi over the winter, but will instead stay with a Great Clan for the season. To host the Winter Court is a huge honor, but extremely costly in both money and effort, and it is impossible to refuse the honor without loss of face. More than one Emperor has used Winter Court hosting as a way to punish people. The traditional requirement, established by the Seppun, is that a kyuden must be able to handle 250 guests at least - 30 from each Great Clan, plus the Emperor's entourage. However, the distinction is more symbolic than practical at this point. The decision as to whether a castle is shiro or kyuden is a matter of face, honor, symbol and politics as much as anything else. Many castles which should be kyuden are designated shiro on maps, even if they've hosted Winter Court, while other castles that are wholly incapable are called kyuden. Shiro Mirumoto, for example, has hosted the Emperor at least twice, and Pale Oak Castle in the Phoenix lands is famously an Imperial winter destination, but is still a shiro. Then there's Shiro Ide in the Unicorn lands, built for the express purpose of Winter Court, which is still not yet called kyuden. On the other hand, you have Kyuden Togashi, which is physically incapable of hosting the court due to being essentially a massive shrine complex in a remote location rather than a castle. (Indeed, no one can ever recall an Emperor so much as seeing the place.) Kyuden Hida is probably theoretically capable of being host to the Emperor, but it would be bizarre in the extreme for the Emperor to inflict the bleak and dangerous lands of the Crab on his court. (A novel claims that Hantei XXXI once did, but it has never been historically confirmed.)

Next time: The parts of a castle.

Castle Guts

Original SA post Emerald Empire: Castle GutsThe heart of any castle is the tenshukaku, the keep, built on a stone foundation. Typically a keep will be three to six floors high, plus the foundation and any sublevels, though a very high ranking lord may have up to nine floors, and Otosan Uchi's imperial palace has ten. The daimyo resides in the keep on the highest floor, both symbolically to demonstrate their station and because it makes it the hardest part for an attacker to reach. Shugenja also often claim it symbolizes the relation between Tengoku and Ningen-do, the Heavens and the mortal world. A lord that fears spies or assassins will often have nightingale floors installed on the upper levels - special wooden floors designed to creak and groan when walked on. Below the top floor will be guest quarters, audience halls, offices, libraries and studios. Most castles also include at least one shrine to the local spirits in the keep, and the sublevels in the foundation will include storage, archives, supplies, an armory and sometimes the barracks. If possible, the basements will also contain a well or cistern, to help withstand a siege. Most also have at least one hidden escape tunnel.

A castle is usually multiple structures, surrounded by maru, the outer walls. Smaller castles or those focused more on politics may have only one set of walls, while larger castles and more martial ones often have several, with narrow passages, isolated courtyards and gatehouses to make assaults harder. The outer walls are generally stone outside of extremely poor or extremely peaceful lands, but the size and thickness of the walls varies by clan and location. Traditionally, the walls are coated in an outer layer of plaster, usually painted white or off-white with clan color decorations, to show a beautiful exterior. Crab castles typically ignore this practice. Walls almost always have a few arrow slits, called yasama, for defensive purposes, though some see no real use. The walls are usually built sloped, with varying levels of steepness. No walls are purely vertical. While this could theoretically make a wall easier to climb, Rokugani masonry is tight-fit and has few handholds, with the smooth plaster being even more annoying to scale. Sloped walls are used because Otosan Uchi has them, and were probably originally meant to be resistant to earthquakes, which are a common issue in the Imperial City. The walls rarely have walkways built in, but heavy logs are incorporated that stick out several feet into the defensive side, which can have wooden planks placed on them to create positions. These removable parapets are known as ishi uchi tama, 'stone-throwing shelves.' While most castles have them, neither Crab walls nor the outer walls of Otosan Uchi's Forbidden City do, instead utilizing broad parapets incorporated into the wall.

Any truly notable castle will reinforce the walls with yagura, towers. There will almost always be two at the main gate, with more at corners and key positions. The more martial and practical the castle, the more towers you get. Kyuden Doji and Kyuden Kakita are notable for having only the two at the gates, while even small Lion or Crab castles may have upwards of five. Towers serve to allow a garrison to spot trouble early, outrange them with bows and use as strongholds in the case of assault or rallying points for a wall breach. The Crab are known to mount siege engines on their towers, but it isn't common in any other clan. A tower is physically much like the keep but smaller, with the lower floors used to house troops or food and the upper floors used as fighting platforms for archers. The bigger the tower, the more sophisticated it will be and the more troops it can hold. The greatest are those on the Kaiu Wall, each of which is practically a castle in its own right. Crane, Scorpion and Phoenix towers tend to the small side and are sometimes more ornaments than anything else. Unicorn castles rarely have many towers because they prefer plains fighting to wall defense.

Any good castle will include at least one barracks to house the garrison, and these are usually highly utilitarian living spaces. Only unwed samurai live in them, as do ronin employed by the daimyo. Most barracks include a small ancestral shrine and secondary armory as well, and they tend to be separate from the main keep, though a small castle may instead contain them in the bottom two floors. Large castles may well have secondary barracks to supplement the main ones. Barracks and other outbuildings are usually wood with a layer of plaster over it, making them more fire resistant than most Rokugani buildings of wood and paper. Each clan uses a different style; the Dragon include small meditation chambers with copies of the Tao of Shinsei, while Lion barracks are usually extremely austere, as they hold the samurai should only be there to eat and sleep, as do the Crab. Crane, Phoenix and Scorpion barracks often have some art and literature inside.

As noted before, any castle has at least one dojo, which technically can be any school but the term is usually used for those that train bushi. In any castle of real size, the dojo is rarely inside the keep but instead within its own seperate structure on the grounds, usually near the parade ground. Very large castles may even have more than one dojo. Typically, a dojo has a central building, a training courtyard around it and one or more student barracks, which connect to the center and are kept apart from the main soldiers' barracks. The main building is the dojo itself, usually one large chamber lined with practice weapons and plaques bearing the names of past students. Even the Crane keep their dojos simple and sparsely decorated, to prevent distraction. Most contain a small ancestral shrine dedicated to the school's founder and past sensei, which students must bow to whenever they enter. Students typically live on-site during training, in large, open dorms in the student barracks, with almost no privacy.

Samurai begin training between ages 8 and 10, training for several years to attain mastery, which is typically earned between ages 14 and 18. When they master their basic techniques, a coming-of-age ceremony called a gempuku is held. The gempuku is a critical moment in a samurai's life, and every family and clan has their own traditions for it. Three elements are common to all, however. Every gempuku involves a test or challenge in which the student displays mastery and dedication to their clan ideals, with varying degrees of difficulty. The Hida often send out their students to return with the head of a Tainted beast of the Shadowlands, but more often a challenge will be a display of kata or recitation from memory of a list of ancestors. Once the challenge is completed, young samurai undergo a ceremony in which they select their adult name, swearing oaths of fealty to their clan and family. Ranking samurai receive these oaths on behalf of the daimyos and champion most of the time, and the higher the rank, the more honor is given to the student and the more effort they will be expected to show. At the end, they receive their daisho, the pair of swords that are theirs by right. These may be new or inherited from an ancestor or family member, and they are the mark of adulthood as a samurai. Even courtiers and shugenja receive them, but their katanas are typically left at home on display stands in a place of honor, rather than carried as a bushi's is.

Next time: More castle stuff.

"Even the Inuit will smile and admit, 'for white men, the Rangers know our land well.'"

Original SA post

Rifts World Book 20: Canada, Part 7 - "Even the Inuit will smile and admit, 'for white men, the Rangers know our land well.'"

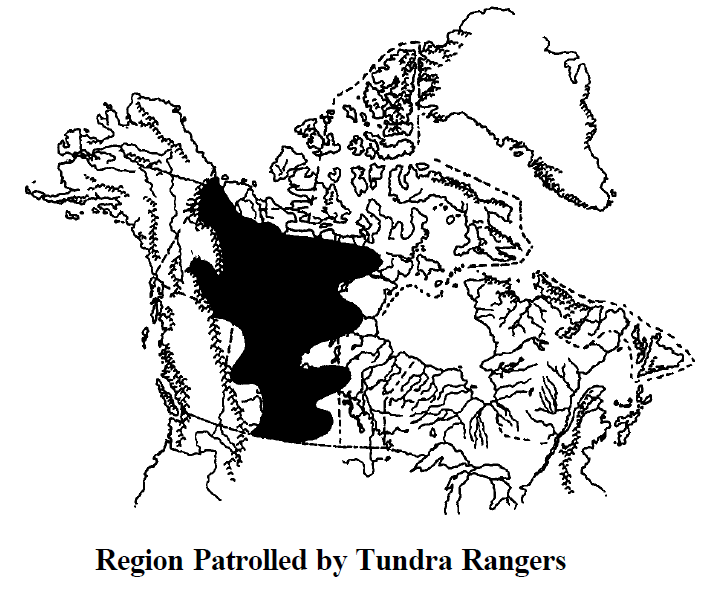

Northern Canada

The Yukon, Northwest, and Nunavut Territories, including Victoria Island, Baffin Island & all northern islands.

Though the tundra is seen as just wastelands to most, the locals benefit from the fact that there aren't many power players that interfere with life here. There are issues with monsters and demons, and rumors of demon worshipers (don't you just hate Canadian Satanists?), and also just the general harshness of the landscape. Most of the locals are the Inuit, who weathered the apocalypse pretty well due to their relative isolation, and D-Bees (like Mastadonids and Sasquatch, detailed later). The Inuit have made a "return to the old, traditional ways" which should surprise no readers at this point, but "half use modern M.D. Weapons". We're referred to Rifts World Book 15: Spirit West for more detail. Where do they get those weapons from, though, if they're so isolated...?

Well, nevermind that, it's time for our cover stars!

Welcome to Battleforce 2000.

The Tundra Rangers

By Eric Thompson & Kevin Siembieda

Founded by survivors of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police who travelled to an advanced military base in the North because...

... yeah, 7,000 RCMP somehow coordinated, decided to go to this base, and help out. Well, maybe they got orders from somewhere? Whatever the reason, they worked and tried to start putting together a plan to restore order across Canada, but were snowed in for a year. And the end of that year, the snows stopped, and when they went out one day suddenly it was Summer! They figured out (somehow) that 265 years had passed outside while it's only been a single year inside. Still looking to help people, they decided to fight injustice and renamed themselves the Tundra Rangers because... uh... y'know. "Mounties" sounds corny to the authors, I guess? Also, you can try and copyright "Tundra Rangers". Maybe these were originally meant to be Canadian Rangers (aka Arctic Rangers), which would fit far better into this concept, but Siembieda decided to make them Mounties because Americans know about the RCMP? I just don't know.

Scouting out, they discovered the Coalition States- and immediately concluded they were "evil and dangerous as they were important to mankind's survival — and best to be avoided". Ah, the necessary evil of fascism. And so, they decided to get on their hovercycles and horses and go around righting wrongs in singlets or pairs! You know, like the Cyber-Knights. Or the Knights of England. Or the Bogatyrs. Or the Justice Rangers. Or the Cosmo-Knights. Or the... whatever they had in Spirit West. I know it was in there. You know. Every area in Rifts needs to have some generic wandering force of do-gooders. Apparently their training in working with indigenous peoples prepared them for working with D-Bees as well, and they're not particularly judgmental.

Also, have we mentioned they're like Cyber-Knights?

Rifts World Book 20: Canada posted:

The Tundra Rangers are the equivalent of the old lawmen and gunfighters of the Old (and New) West, or the high-tech Cyber-Knights of the north.

Rifts World Book 20: Canada posted:

Like the Cyber-Knights, the Tundra Rangers defy tyranny and tirelessly fight monsters and help people, from the ranchers and towns in the south to the inhabitants of a tiny farm or lone individual in the wilderness.

Rifts World Book 20: Canada posted:

The Tundra Rangers have became something of living legends nearly on the scale of the fabled Cyber-Knights, and are the symbol (some would say living embodiment) of law, order and justice.

Rifts World Book 20: Canada posted:

Tundra Rangers are always on the move, like enigmatic superheroes or knights old, and seem to appear wherever they are needed.

Or that they work with Cyber-Knights?

Rifts World Book 20: Canada posted:

The constant and growing trouble with demons and monsters from the Calgary Rift is of grave concern to the Rangers, and they frequently exchange information and join forces with the Cyber-Knights in their efforts to contain and destroy the gathering evil.

Rifts World Book 20: Canada posted:

Cyber-Knights and Tundra Rangers regard one another as close allies and have fought many great battles together.

Rifts World Book 20: Canada posted:

One such battle involved a skirmish near Calgary where 500 Cyber-Knights and 4,000 Tundra Rangers are said to have fought and slain over 1,000 demons and their mortal minions.

Rifts World Book 20: Canada posted:

Lone operatives, pairs and even squads are allowed to work with other lawmen, Cyber-Knights, adventurers, mercenaries and local citizens to resolve these problems and keep the peace.

Or they have a code? Codes are cool, right? Like a knight! It tells them to do good stuff and be honest and fair and stuff.

"And we will protect this ink stain by any and all means!"

They don't have cornball red uniforms but instead look like cool arctic ninjas with a Maple Leaf on their shoulder! They emerge from the snow and solve problems with guns and nobody knows where they come from, because their base is super secret! But they still fly the Canadian flag over their secret base and make people proud about the flag because reasons!

They do recruit new members, of course, and about 25% of them are "Native Americans" (er, Indigenous Canadians / First Nations). And 60% of those are magical!... the rest are "Modern Renegades" that use guns and don't even care about the spirits, mannn. Makes for some interesting times on the break room, I'm sure. (Also, that means like 15% of Tundra Rangers are essentially shamans of one stripe or another, though I'm not sure that's been really thought out given they use tech all the time.) They apparently got enough respect with the Simvan Monster Riders after battling them that some Simvan joined them, too.

"We're Tundra Rangers!... look, Siembieda couldn't be bothered to have somebody draw uniforms on us, just take our word for it...

Also, you'd better not mess with then because they'll bring you to tundra justice!

Rifts World Book 20: Canada posted:

And everyone knows they are relentless in this task, and that the "Tundra Rangers always get their man!"

Of course, because they're tundra knights, they have their code, guides them to keep people safe, mete out justice, be tolerant of diversity, "never doubt the good we are doing", believe in themselves who believes in themselves who believe in them, keep their word, stay loyal, and-

Rifts World Book 20: Canada posted:

• One person can make a difference. Never doubt it.

• A Tundra Ranger never stands alone.

Sure, makes sense.

We get a bunch of notes and numbers on them. About 9% die annually, 5% go missing, and 2% go AWOL. But then right after that we're told they're sent out individually to go be lone wanderers. Maybe you shouldn't do that, Tundra Rangers! Respect the buddy system! In addition, they're only expected to check in every few weeks to two months. If one goes all loose cannon, though, they become persona non grata and everybody hates them, so if you play one you better toe the line and follow orders or else the pass-aggy GM will get you! Even if you go out of contact for reasons not your own, you'll catch a bunch of shit because they'll try and search for you and they haaate doing that.

But enough of sticks, then we get some carrots. Like how well people treat Tundra Rangers and give them a warm meal and a soft bed and a temporary horse loan. In addition, they can requisition equipment, but-

Rifts World Book 20: Canada posted:

Other factors include basic supplies and the overall personality of the commanding officer (if he has a disliking towards the character, the availability of options may become very constricted).

The passive-aggressive officer always short-supplies his man!

You can tell they're a future ranger because goggles.

Of course, we also get some new classes. Also, since we have new saving throws, they get bonuses on saving against cold! Exciting. As always, the % is the chance to qualify to play one as a human.

- Tundra Ranger O.C.C. (33%): Despite a lot of talking-up, Tundra Rangers are pretty much just more combat-oriented Wilderness Scouts with modestly better equipment. They get some solid combat bonuses, but their +1 bonus attack per round is about the only thing that sets them apart.

- Tundra Ranger Scout O.C.C. (23%): Tundra Ranger Scouts are pretty just more... hm... just more Wilderness Scouts. We're told "nearly half are Native Americans", of course. Another third are D-Bees. Of course, of course.

- Tundra Ranger Cavalry O.C.C. (39%): This is mainly a class for D-Bee and mutant members like the Simvan, Psi-Stalkers, or the "Horsemen of Ixion" we'll see later, though there are Indigenous Canadians a well. They ride animals!... or themselves, in the case of Horsemen. Of course, we're told the Simvan don't wear uniforms because they "dislike heavy armor and confining clothing". Apparently they also like freezing their tuckuses off and getting shot in head, the two consequences of that preference. The class? It's like the Cowboy, only a Ranger, I guess?

The Trapper-Woodsman-Football O.C.C.

And now, a surprise interview with the Trapper-Woodsman O.C.C. (31%).

quote:

ARB: This is the Tundra Ranger section. Why the hell are you here?

TWO: Y'sure? I thought this was just a bunch of generic wilderness classes, figured I'd fit right in.

ARB: ... so I've actually seen like, a lot of survivalist character classes in this game. Dozens, maybe. What do you think you bring to the table?

TWO: Oh, I've got this new ability, eh? It's called track & trap monstrous animals, otherworldly creatures & demons. Ain't nobody got that!

ARB: How is that different from like, the normal tracking or trapping skills?

TWO: Well, I can apply it to monsters and demons, don'cha know?

ARB: Can't you already apply tracking or trapping to those?

TWO: This is specifically for catching those otherworldly buggers, though. I'm better at it than some old wilderness scout or hoity-toity Tundra Ranger!

ARB: How are you better at it?

TWO: I'm specialized!

ARB: Okay, do you do it faster, or do you know more, or-

TWO: I said, I'm specialized! That makes me better!

ARB: Fine, um, what's this - Forest-wise?

TWO: Get this, it's like streetwise. But for the forest.

ARB: Oh, get the fuck out. Get the fuck out of here. You're just another goddamned warmed-over treefucker-

TWO: Wait! Wait! Hold up! Sorry, just- don't be so quick to judge, I've got something to show you.

ARB: Nobody cares about your "+1 to save vs posession". Nobody. Literally noone. Not even Palladium devotees care.

TWO: I've got... baggies.

ARB: what

TWO: Says here under my equipment: "a box of 100 plastic sealable sandwich bags". Oh, I know you're impressed, but that's not all.

ARB: Why did they write- who on Earth cares-

TWO: Also: "a box of 100 large sealable bags" See? Let's see some Tundra Ranger pull out a storage solution like this?

ARB: Okay, no, seriously, I want you gone.

TWO: I have 4 "airtight (resealable) plastic containers"! It's tuppin'ware! I had to roll 1d4 to see how many I got and I rolled a 4.

ARB: I am- I am done! Here!... with having to comment on another roughin' it toughin' it generic mountain man motherfucker livin' off the land, we don't need another class with "Skin & Prepare Animal Hides" like anybody cares, and- what- what are-

TWO: *sobs* but I have tuppin'ware *sobs*

ARB: Shit. I- look, it's okay, I thought you had +2 to save vs pain, I guess- fuck, I thought you'd make that saving throw- look, let's just turn the mic off-

Next: Calgary, the heart of evil.

Ranbo - First Blood

Original SA post Emerald Empire: Ranbo - First BloodA mizuki, that is a moat, is not universal to Rokugani castles, but does show up with decent frequency. Usually a moat will be placed outside the exterior walls or between wall layers as part of a multilayered defense. Putting it directly around the keep itself is both rare and highly impractical in most cases anyway. Most moats, however, contain no water, in favor of just being empty ditches. Some skilled architects do redirect mountain streams, however, to make for a clean and constantly renewed moat that relies on prayers to the stream's kami or wards on the foundation to prevent erosion. Bridges across moats are always designed to be easily collapsible during an attack. Moats are most common in Crane, Scorpion and Lion castles as well as those of the Imperial family. Unicorn, Dragon and Crab castles almost never have them, although the River of the Last Stand does sort of function like one for the Kaiu Wall.

Smaller castles will usually maintain their guest housing within the keep itself, but a large complex will have one or more outbuildings to be dedicated guest quarters. In any major castle expected to host significant diplomatic meetings or Winter Court, there will be seperate buildings for each Great Clan, to allow them to hold private meetings without being overheard. These guest houses will in essence be large normal housing for samurai, with all the amenities the host clan would offer to its own. Crane guest quarters are thus the best short of the Imperial Palace, while Lion and Dragon castle guest housing tends to the more austere. The Crab rarely have dedicated guest housing at all except in the Yasuki family palace.

All castles will have at least a small courtyard within the main gate, usually in front of the keep. This is the parade ground, where the soldiers drill, guests can leave their mounts and the lord can give speeches to their men. In a large castle, the space will be larger as well, and in massive castles such as Kyuden Hida or Shiro Sano ken Hayai, it is large enough to host a thousand soldiers at once - or more.

Every samurai's home must have gardens, including castles, to allow the samurai to seek harmony in the carefully curated natural world. In small or simple castles, there's usually just one small garden, usually in the first floor near the court chamber. Larger castles will often have secondary gardens, often with one on an upper balcony for exclusive use by the lord's family. Obviously these all take significant upkeep from the servants and sometimes a specialized artisan samurai, so they do cost. In a really grand castle, an entire part of the castle complex may be set aside for an outdoor walking garden with ponds, bridges, walkways and so on, probably even shrines to the Fortunes or ancestors. The most famous of these lie in Kyuden Bayushi and Kyuden Doji, but they are hardly alone.

While some castles stand alone, most coexist with a nearby town, or jokamichi. These towns form because the castle is both the safest place in the territory and the seat of government. The Crane encourage the practice, while the Lion discourage it in the belief that it weakens the castle's defenses. Castle towns typically draw in merchants, artisans and other skilled peasants, and most of the castle's servants will live there, though some live in the castle proper. Farmers are rarer, as most castles rely on imported food anyway. There will also be certain classes of hinin attracted by the local samurai - actors and geisha, mainly. Some towns grow large enough to become full cities with thousands of people, and when this happens the local lord will usually build a wall around the city for defense, separate from the castle's own walls, so that if the city is captured, the castle can hold out.

A castle will also always have a small stable at least for the mounts of the lord and their retainers. For those that regularly receive visitors, the stables will be much larger and have spare mounts for guests to use, as well as dedicated and skilled staff. Unicorn stables are, naturally, considered vital to any Unicorn castle, and will be far larger and more elaborate than any others, often with samurai on staff to train the horses.

We now get into the first example castle: Toshi Ranbo wo Shien Shite Reigisaho, Violence Behind Courtliness City. It was originally built as a small four-story castle, but it has been a focal point of Lion-Crane fighting for centuries and has grown to be very important. Its name comes from the constant fighting and subsequent diplomacy and peace treaties. Physically, it is a medium-sized fortress on flat land, four stories tall with its own separate barracks, guesthouses, small court chamber added by Crane architects, ancestral shrine and large shrines to Hachiman and Bishamon. It has a two-tower wall, and beyond the inner fort is a larger walled compound with its own gates and towers, plus extra barracks, training grounds, dojo and quarters for officers and servants.

Why is a minor Lion castle the focus of so much conflict? During the early Empire, the Crane were given control of Kintani, the Golden Valley, which is an isolated but valuable piece of land near the Imperial City. In the 400s, the Lion built a castle called Kita no Yosa, the Northern Fortress, to watch the Crane. The castle was granted to a minor vassal family, the Goseki, who spent 500 years fighting the Crane off and on. The peak of the conflict happened in the 600s, when the Crane twice made major attacks, one of which captured the town for eight days, though not the castle. The Lion went on a retaliatory offensive which nearly captured Kintani entirely. The castle town thrived enough to become the current city of Toshi Ranbo, but by the 1100s, a new wave of fighting made it shrink back to village size, with barely a few hundred people. This shrunken settlement was taken by Tsume no Doji Retsu, ruler of the Kintani and daimyo of the Tsume vassal family of the Crane. In a surprise assault, he utterly eradicated the Goseki family and claimed Toshi Ranbo for the Crane Clan, which the Imperial Court later upheld due to Crane political dominance. The Daidoji were given command of the castle, improving its defenses and adding gated walls around the cillage to ensure the Lion couldn't seize it back. Later Lion campaigns to retake it failed due to Crane politicking and losses in battle, with both sides escalating their military commitments to the region. In 1123 (IE, very recently), a major battle cost the life of the Lion Champion, Akodo Arasou, and so Toshi Ranbo currently has an outsized weight in current events, well out of proportion to either its size or its actual tactical value.

Every location given has several rumors and an adventure seed written up, plus a major NPC. The rumors may or may not be true as the GM desires.