Ars Magica: The Contested Isle by Mors Rattus

Ireland is Magic

Original SA post

A thread may be ending, but

I got a new Ars Magica book.

Ars Magica: The Contested Isle

That's right! A new book! The Contested Isle is the latest Ars Magica book to be published. It focuses on the Hibernian Tribunal - that is, Ireland. (For those interested, the next book on the publishing schedule is Transforming Mythic Europe, which will be about wizards advancing the social and technological status of the world and how it might happen, as well as the potential consequences. How many other settings give you a book on how to utterly destroy the setting?)

As an overview: Ireland is fucking

loaded

with magic. It's all over the place. It is also full of violence. The English recently conquered the place, and the Tribunal is at a tipping point, as many factions push for power. The Irish don't band together well, though - they're as likely to raid each other as anyone else. The Tribunal's traditions, created by mostly Tytalus and Merinita, encourage rivalry and challenges, and relationships are complex. They fight each other, but protect the local hedge wizards, and have even given land over to them. But let's stop this overview and go in detail.

When the world was made, Ireland was only half-finished. It had forests, but no water, no animals, no meadows and no people. Five waves of settlers came to it before the current people, the Gaels or Milesians, depending on what name you prefer. These are known as the Five Peoples. They found the chaos of ancient Ireland, unformed, and they made it what it is now. The Irish have recorded this history as one seamless tale in several books, most famously the Lebor Gabala Erenn, the Book of the Taking of Ireland or the Book of Invaders. There is also the Lebor Laignech, the Book of Leinster, in the monastery of Tir-Da-Glas.

In any case, Ireland's first invaders were led by Cessair, granddaughter of Noah. Her grandfather ordered her to find a land untainted by human vice, and she hoped Ireland would be a safe haven from the Flood. It wasn't. Cessair and her people fled to the mountains of Ireland, but they drowned when the waters rose too high. Only one survived: Cessair's druid, Fionntan, who turned into a salmon. Legend has it that he had three other forms - stag, eagle and boar - and that he still lives today.

The second group left a greater mark. They were Greek, followers of the prince Partholon, and they brought with them art, craft and cattle. They cleared four great pastures from the primeval wood and saw the birth of four great lakes. They also found the Fomorach, monstrous giants from the northern islands. The Fomorach settled in the north and raided the Partholonian. Eventually, there was a grand battle, in which the tribe of Partholon killed the Fomorach, but in so doing, they doomed themselves. They left the giants' corpses on the field, and a plague came forth from them, killing all the tribe.

Third were Scythians, the tribe that followed the man Nemed. Nemed did not seek Ireland - he was just fleeing Scythia for fear of the punishment for his patricide. He and his tribe took a great fleet, following the sight of a great golden tower that rose from the sea to the west. This tower, built on an island, could be seen only at low tide, for at high tide, the waters covered it. After landing on the island, the tide took Nemed by surprise and destroyed most of the fleet. It was a year before the Nemedians saw land again, landing on Ireland by accident. They brought their soldiers, their families and their druids, bringing lore and craft to the wilderness. They cleared plains and saw lakes erupt forth for them, and their prosperity, like that of the Partholonians before them, brought the attention and greed of the Fomorach.

The Fomorach came from the northern oceans, capturing Nemed's tribe and demanding tribute. Nemed had died by this time, and his sons and grandsons suffered under Fomorach rule. The Nemedians plotted to rebel, sending to Greece for aid. The Greek king sent them soldiers, druids, druidesses, wolves and venomous beasts. With their aid, the Nemedians assaulted the Fomorach fortress on Tory Island, destroying it. Still, the victory was short-lived. Fomorach reinforcements attacked, and the Fomorach druids used terrible water magic to drown the battlefield, slaughtering the Nemedians and many of their own. At the end of the day, many of both sides lay dead, but the Fomorach had won, devastating their human foes. Three surviving grandsons of Nemed split their remaining followers into three groups, departing. The isle remained free of humans for two centuries.

Fourth to invade were the Fir Bolg. Legend has it that they descended from one of Nemed's grandsons, who was a slave in Greece before escaping and returning to Ireland. The tales of the Fir Bolg journey are grand, telling of epic battles against the dead and demons, but fail to tell how the Fir Bolg became Magical beings. 'Fir Bolg' means 'the men who swell with battle fury,' though some false believe it means 'men of the bag' because their Greek slavemasters made them move earth in leather bags. The Fir Bolg divided Ireland into provinces, invented kingship and justice and brought peace to the land. More on them much later.

The fifth invaders were the Tuatha De Danann, the last wave before the modern Gaels. After the Nemedians warred with the Fomorach, one of their groups started to worship Celtic faeries, who took the group to their mystical homeland in the north. In four fabled cities, the faerie Tuatha De taught their people culture, art and magic, interbreeding with them. When they returned to Ireland, the faerie gods came with them, as did their children and their druids. More on the Tuatha De Danann later.

In any case, the Fir Bolg and Fomorach ignored the requests for peace laid before them by the Tuatha De, seeking war. At the Battle of Moytirra, on the Plain of Cong in the province of Connacht, the Fir Bolg were defeated by the invaders, but in victory, the leader of the Tuatha De Danann lost an arm, making him unfit to rule. His chieftains chose a new leader, a son of Tuathe De mother and Fomoir father, in the hopes that it would keep the Fomorach at bay. It didn't. The Fomorach came and conquered the newcomers. However, at the Second Battle of Moytirra, once more in Connacht but on a different plain, the Tuatha De defeated the Fomorach, driving them from Ireland. They laid a curse on their giant foes: none of the Fomorach might set foot on Irish soil without suffering dire consequences. That's a literal curse, mind - air and water are fine. A Fomoir that can swim or fly is just dandy so long as they do not touch the soil. The Tuatha De Danann kept the Fir Bolg ways, their kingships and society. The gods lived among their mortal followers until, eventually, the human population grew so much that human kings replaced the faeries. The rule of the Tuatha De was not peaceful, and fights over cattle, land and succession frequently led to war. The peaceful culture sought originally by the gods was forgotten.

The latest and last invaders were the Gaels, descended from Gaedheal Glas, builder and linguist. Legend holds that he created the Irish tongue from the best parts of the 72 languages spoken at Babel. The Gaels came out of Egypt, heading, eventually, to the northern coast of Spain. Legend has it that they built a tower so high that the knight Mil could see Ireland from its summit. It was foretold that Mil's sons would rule the island, so he sent his uncle and a small force to investigate. They were slain by the Tuatha De. Mil sent a greater force, captained by his eight sons, and so the Gaels are also known as the Milesians, the sons of Mil. They were led by the poet-sorcerer Amhairghin, and they defeated the Tuatha De with violence and magical trickery. The faeries fled underground, promising to leave the island to its new rulers. The mortals of the Tuatha De tribe were brought into the tribe of Mil.

In their conquest, the Milesians found three goddesses of the fae: Banba, Fodla and Eire, each promising victory if a son of Mil would marry her and each claiming to be Ireland. Three sons agreed, and to this day, the tradition of a provincial ruler ritually marrying a land-goddess is maintained. Mil's uncle and three of his sons founded the Four Root Races, the four great tribal lines of Ireland. The son Eremon settled Connacht, becoming first of the Connachta tribe. The son Eber took Munster, giving rise to the Eoghanachta. The son Eibhear settled in Ulster, fathering the Erainn. And the uncle, Lughaidh mac Ith, took Leinster, becoming ancestor to the Laigin. Eventually, these tribes and the lesser ones fought each other and themselves, over cattle, land and leadership.

The two greatest brothers, Eremon and Eber, split the island between them, marking their boundary line by the Eiscir Riada, a line of sand and gravel ridges running from Galway Bay to Dublin. Eremon took the north and Eber the south, but Eremon slew Eber and claimed all of the island. He delegated rule of the five provinces to sub-chiefs, kin-vassals of his who would ultimately destroy his authority and create their own dynasties. One rose to prominence, claiming the high kingship, only to be replaced by another, a pattern that would be followed for two thousand years.

Centuries of war followed, giving rise to great heroes. The greatest of these was Cormac mac Airt, who ruled in the early 200s. He was protected from birth by five magic wards, such that he could not be hurt by drowning, fire, druid magic, wounds or wolves. He became high-king at age 30, and in his reign, the land flowed with fish, honey and fruit. His grandson, Conn of the Hundred Battles, was a Connachta leader, whose deeds were so great and whose sons so numerous that many now claim him as an ancestor. He discovered many of the hidden treasures of the Tuatha De, including the five roads of Ireland and the ancient yew named Mughain, the center of the faerie otherworld. He grew up in Leinster, overthrowing the ruling high king to win the tree, then raiding the Eoghanachta king of Munster, King Eoghan Mor. He was too powerful to be easily defeated, though, and the pair again split Ireland on the ancient boundary, dividing it into Leth Cuinn in the north for Conn and Leth Moga in the south for Mor. Conn, however, broke the treaty afterwards and defeated the Eoghanachta at the Battle of Magh Leana.

There were other heroes, to be sure, who never became high kings. The provincial king Ailill of Connacht and his wife Medb were fierce leaders, often at war with the king of Ulster, Conchobhair mac Neasa. Clan champions were as important as kings, too - most famously Cu Chulainn, Ulster's champion, and Fionn mac Cumhaill of Leinster. The lists of heroes and kings are immense, memorized by poets to recite grand genealogies. The Fir Bolg stayed in Connacht in this time, the Tuatha De Danann underground and the Fomorach offshore. All left the Milesians alone, keeping to their old pacts. Certainly, people met individual Fir Bolg and Tuatha De, but no more than that. The early Milesians kept guard against the Fomorach, but after generations without sighting their ships, the lookout was abandoned.

Next Time: The coming of Christians and wizards.

Ireland is Catholic

Original SA post Ars Magica: The Contested IsleThe first Christians to come to Ireland were not people you've probably heard of. Everyone knows Patrick, but he was not the first. The first was Palladius, who came with his assistants, Auxilius and Secondinus. He brought the teachings of Ambrose and Augustine, but when he landed in Clonard, the Irish did not welcome him. No one knows what happened to him in Ulster, but he did not succeed in his goal of conversion. Patrick came later, in the fifth century, though the date is unclear. He was a slave, captured by Irish pirates raiding the English, but his guardian angel, Victor, helped him escape. Still, Patrick heard a divine message telling him to convert the Irish, and as an adult he returned to preach. He made a circuit of the island, from Leinster to Connacht to Ulster to Meath to Munster. He performed miracles, casting out the snakes and defeating and exiling druids after a magic contest. He used a three-leaf clover to explain the Trinity, and he was overwhelmingly succesful, becoming the 'Apostle of Ireland' and cementing Christianity in the hearts of the people. He is now interred in Down Cathedral.

A few centuries later, in 778, two Tytalus and two Merinita magi came to the isle, seeking the legendary treasures of the Tuatha De Danann. With the help of a local ward-maker, they discovered the Dagda's cauldron buried in the mounds of the Bru na Boinne. However, the high king noticed their grave robbing and sent a druid and warband to confront them. The magi find a barrow they could defend, and the ward-maker protected it with his magic. They sent the first attack away, but the druid swore to them that the king's men would come again by morning. The lead Tytalus replied to him: We will defend this mound for a year if need be! They repelled the morning's attack, and two more attempts over the next three days. Keeping to their boast, they remained at the mound a full year.

After that, they decided to stay, and relocated to the western shore of Munster, again saying they'd defend their location for a year to prove themselves. They named the plce Circulus Ruber after the wards of their local assistant, and in two years it was a full covenant, the first of Ireland. Thirteen years later, Diedne came, hoping to recruit the druids of Ireland. They rejected her, and she spent the next seventeen years murdering every druid she could find. Cuin-dallan of Ulster, known to the Order as Quendalon, returned from Germany to save what he could of the older magical traditions. Aided by his House, he brought some into Merinita and hid others in Connacht. Meanwhile, House Diedne formed covenants in Ireland. By the early 9th century, there were still many native traditions, some hidden, some protected by kings or Hermetic allies and some strong enough to fend for themselves. Some of them joined Pralix in her war against Damhan-Allaidh, and the survivors eventually became the core of House Ex Miscellanea.

In the meantime, Norwegian and Danish Vikings began to raid Ireland in the late eighth century, focusing on the wealthy monasteries. They were named Ostmen by the Irish, meaning 'Eastmen', for they came from the east without warning. At first, they came only by spring and summer, but by the turn of the century they decided to stay for good. They seized and converted Irish coastal ports into permanent settlements. Every major Irish city, including Dublin, Waterford, Wexford, Cork and Limerick, was made by the Ostmen. They brought their rune wizards with them. The Order, having been in Ireland but 20 years, were not prepared for the Scandinavian aggression. At the Grand Tribunal of 832, the magi of Hibernia called the Ostmen wizards 'the Order of Odin,' and uncertain of their strength, they sought peace. Mael-tuili of Merinita met with the rune wizards of Dublin, promising tribute, but he was attacked and slain, along with most of his group.

Still, the Vikings were worse in other areas, and most of the Order stopped paying attention to Ireland. Many Hibernian magi had hoped the Ostmen threat would unite the Order in Ireland, especially the quarreling Ex Miscellanea and Diedne, who had never gotten along. (Diedne and Pralix, in fact, tried to kill each other at least once.) The tensions did not resolve at all - in fact, more tensions arose, between Hermetics and native wizards. Battles against the rune wizards, raids against druids and certamen duels were common. While individually weaker than magi, the Irish native wizards were members of the existing tuatha and could call on kings for aid. Border disputes and skirmishes over resources were a constant problem. To end this, the Irish magi agreed to acknowledge the Coill Tri, a confederation of hedge wizards that had earned the title of druid, and to make peace with them. House Diedne refused to join in this agreement, but on the verge of what seemed to be open war, they retreated from Hibernian politics. In 851, the Primus of Diedne, Obregon, announced that Diedne magi would no longer protect their "undeserving sodales", and the Diedne of Ireland retreated to their covenants. In their absence, the Trey of Cnoc Maol Reidh was signed. More on that later.

Still, House Diedne had a dominant position in Ireland. They refused to recognize the Treaty and entered Connacht regularly. As a result, hedge wizards made treaties with individual magi for protection. Adapting the concept of amici, with the moral duty to support and wage Wizard's War for each other, some magi became protectors of the natives, though always in a one-to-one relationship. These agreements stopped some Diedne raids, but were ineffective against raiders from England and Scotland. In 865, the Hibernian magi raised this point at the Grand Tribunal, but were told that their treaty was illegal, and that since Ireland was part of the new Britannian Tribunal with England and Scotland, they had to obey the Britannian Peripheral Code. Already upset, the Irish magi explained the importance of the Treaty of Cnoc Maol Reidh, saying that given the choice of joining or dying, the Irish hedge wizards preferred greatly to fight and die - a course that would destroy their traditions. The treaty would allow them to continue, perhaps to be explored and incorporated into Hermetic theory. Invading magi, they said, threatened the accord...but to no avail. The Grand Tribunal would not recognize it.

Thirty three years later, after the Tytalus showed that a Tribunal could secede, the Irish magi left the Britannian Tribunal, forming the new Hibernian Tribunal, which immediately ratified the Treaty of Cnoc Maol Reidh. Every individual treaty between hedge wizard and magus was made binding, and those who had ignored such treaties were brought to helel. With the external raiders stopped, Hibernia focused on internal conflict. The intrinsic rebelliousness and aggression of the Irish gave rise to several foundational cases of the Hibernian Peripheral Code. Local rulings on treaties, trophies and legal raiding were a safety valve for Irish violence - allowing contained conflict, it was thought, would prevent greater war.

The 10th century was a violent one, Irish and Ostmen fighting each other and themselves. The Hibernian magi, prohibited from getting involved in royal conflicts, followed their own interests. The Diedne magi were plentiful, but stayed behind closed doors, while the Coill Tri stayed in Connacht. The threat of war with the Ostmen wizards never happened, though skirmishes were frequent. The Irish clans kept the interior, the Ostmen kept the coast. As the Ostmen converted to Christianity, the two groups began to merge and cooperate, mixing OStmen mercantile efforts and Scandinavian mercenaries with Irish beef and leather. In the meantime, the Irish magi igored the growing skirmishes in Normandy and Provence. They were rather more concerned with the Munster kin Brian Boramha, known to the English as Brian Boru, who was making a bid for the high kingship. He lead thousands of men, aided by Munster druids and hedge wiards, and many believed that he could unite Ireland. Thus, the Schism War took the Hibernians by surprise.

The Tribunal contained six Diedne covenants. Some magi were reluctant to attack them, for they had not been a problem in ages, but others were swift to act. To their shock, three of the six covenants were empty when attacked, their members fled to other covenants, either on Ireland or elsewhere. Overeager, the Hibernian magi split their forces and attacked each of the three that remained at once. But the Diedne had made alliance with the supernatural powers of Ireland in anticipation of these assaults. Suil Braddin, the covenant Salmon's Eye, was a Diedne group in Munster that joined forces with Donn, Tuathe De god of death. Scornach Baintri, the Widow's Throat in Ulster, had enlisted a fleet of Fomoir warships. Five of these ships sailed up the River Shannon, while five attacked the coastal covenant of Circulus Ruber. The third Diedne covenant, Culraid Logha (Lugh's Retreat) was in the Hollow of Shannon, a remote spring in the Dartry Mountains that fed the River Shannon. The split force regrouped to relieve Circulus Ruber, defeating the Fomoir fleet there...but that left the other ships free to reach Culraid Logha.

With Circulus Ruber secured, the Hibernians attacked and destroyed Scornach Baintri. Twom onths later, they tried to do the same to Culraid Logha, but failed. Almost a yer after that, the Munster Diedne and Donn's forces destroy Cosan Crolaire (Warbler's Way), a covenant near Lough Leane. The Hibernians united to defeat the Munster Diedne, razing Suil Braddin and forcing Donn to return to his island. With their forces weakened, they still gathered one last time to attack Culraid Logha. As the day of the attack grew near, two years to the day since the first assault, the druids and hedge wizards of Connacht came to join the fight, informed of it by Mercere messengers. The combined force destroyed Culraid Logha, killing the Diedne and the Fomorach defending it. This battle is known to poets as the Third Battle of Moytirra. The Hibernians believed Ireland to be free of the Diedne, but they were wrong.

Brian Boramha continued to move across Ireland, having taken Ulster and Connacht. He went next for the Ostmen of Dublin, but as they marched east, Boramha's druid, the dwarf Muircheartach mac Lia, told the Flambeau magi of Lambaird that Boramha had druids with him who named themselves 'sons of Diedne.' The Lambaird magi realized that some Diedne magi must have survived, and they headed to the battle. The Irish and Ostmen clashed at Clontarf on Good Friday of 1014. As they battled, the Flambeau traveled the field, hunting the Diedne. Their battle was brief, flamboyant and deadly. By the end of it, no Diedne magi lived on Irish soil. The Irish defeated the Ostmen, ending their threat forever...but Boramha died in the battle. His army returned to Munster, to weak to conquer the island.

The war of Brian Boramha upset the balance of power. By destroying the Ui Neill control of the high kingship, he showed that whoever had most power could become high king - and that it was worth fighting for. Many tried, and the next two centuries saw high kings from all provinces. Not all ruled unopposed - some were known as the ri co frasabra, the high king with opposition, as some clans would not acknowledge them. No high king was able to keep the title long enough to pass it to an heir, and violent power grabs became routine, as did raiding, destruction and mutilation of rivals. The pattern went on without end, and many think the English are just continuing it now.

In the meantime, the Irish Church had its own problems. The laity were lax, tithes went unpaid, violence against clergy was commonplace and many sacraments were ignored. Priests married and passed benefices to their children. The archbishop of Amnragh, Mael Maedoc (remembered by Europe as Saint Malachy) went to great lengths to reform the Church. Due to his efforts, ratified in 1152 at the Synod of Kells, many of the worst excesses ended. Ireland was split into 36 sees, with four archbishoprics at ARmagh, Cashel, Dublin and Tuam. Despite this, the Irish Church remains notably different from that of Rome. More on that later.

Despite all the violence and tumult, the 12th century was a time of great art, too. Books were made in greater number than any past era, driven by the desire to record and remember the old ways. Several monasteries became expert with vellum, while others became famous schools for illuminators. Hermetic magi added to the demand, and it's a rare Irish grimoire that isn't highly decorated. Gold and silverwork was common, but all these fine arts are hidden by the half-deserved reputation of Ireland as a barbaric, violent and lawless domain.

The English were soon to change the Tribunal forever. In 1152, Diarmait Mac Murchada, King of Leinster, abducted Derbforgaill, the wife of the King of Briefne, Tighearnan Ua Ruairc. This was the catalyst for great tragedy, and to this day, Derbforgaill is remembered as the Irish Helen. She herself was quite happy with things, settling in with Diarmait, but Tighearnan invaded Leinster in 1166, and the men of Ossory rose to rebel against Diarmait. He lost his throne and fled to English exile. There, he sought aid from Henry II to recover his lands. The new High King, Ruaidri Ua Conchobair, had taken Leinster, and Diarmait was unable to persuade Henry to invade. Instead, he gathered mercenaries to do the task himself. When this failed, he turned to the Marcher Lord Strongbow of Wales, EArl of Pembroke. Strongbow agreed to help, invading Leinster and placing Diarmait back upon his throne. Diarmait's rage at his old foes was infamous, and after one battle against the men of Ossory, he had his English allies make a pile of two hundred severed heads, searching through them for one particular foe whom he hated especially. He chewed the lips and ears off that one. Strongbow married Diarmait's daughter Aoife, and on Diarmait's death, he took the throne of Leinster. This, according to many Irish, was agaisnt the Brehon Laws, but the power of his mercenaries was too much for anyone to act against.

The success of Strongbow worried Henry II, who headed for Ireland to bring the man to heel. Strongbow immediately surrendered, and once in Ireland, Henry demanded vassalage from the Irish kings as well, who gave him tribute. In 1185, seeing his barons carving out land in Ireland, he sent his John to be Lord of Ireland. Prince John set off to receive homage, accompanied by the Welsh priest Gerald of Wales. Gerald went on to pen two popular books on his experiences, the Topography of Ireland and the Conquest of Ireland, which showed the Irish as savage and exotic. Few in England and Wales knew anything of Ireland, and Gerald became popular for giving public readings of his book to massive crowds. Prince John was much less successful. He was only 17, and his tactlessness was already legendary. (It would lead to the English Baron's Revolt later.) When the Irish kings came to do him homage, he openly mocked them and tugged at their beards.

For many magi of the Stonehenge Tribunal, Gerald's texts were a wake-up call. Some had visited or met Irish magi, but the ORder in Ireland was insular and little-known to others. Many had heard of the marvels of Hibernia and heard stories of vis so plentiful that it was left unharvested, tales of a quarter of the isle left untouched by Hermetic magi, where druids still ruled. Hibernia was suddenly the talk of Stonehenge Tribunal, a place of mystery, wealth and danger. Some feared Connacht - what if the Coill Tri were the secret heirs of Llewellyn, last Primus of Diedne? What if the Order of Odin had a foothold in the Ostmen? Henry's conquest of Ireland was justified with a reference to the Papal Bull of Loudabuiliter, in 1155, which could be read as giving him the right to conquer Ireland and reform its Church. The reforms of the past century had made it moire like that of England and the continent, and in the same way, the Order of Hermes in Stonehenge were becoming disturbed by the customs of Hibernia and began to talk of a need to reform it. A few Stonehenge magi attended the next Hibernian Tribunal, and were shocked by what they saw.

Next Time: The English expand.

Ireland is English

Original SA post Ars Magica: The Contested IsleIn the meantime, Hugh de Lacy conqueres Meath, and the King of Briefne dies at a peace parley, possibly of assassination. The English move into Munster and Ulster, but Connacht, home of the High King Ruaidhri Ua Conchobhair, remains free. Ruaidri submitted to Henry, but his continued autonomy caused the magi of Stonehenge to fear the potential of the Coill Tri and what they might be doing and represent. After all, it made no sense to them that Connacht avoided all harm. With increased English presence, several English magi traveled through Ireland, and many felt their suspicions justified - especially in 1190, when a traveling group was attacked by what seemed to be a young Irish magus. The English magi, knowing nothing of the Irish custom of macgnimartha (more on that later), were very upset when Damisona of Jerbiton was attacked and three of her grogs killed. This led to a great outcry for something to be done about Hibernia.

The Grand Tribunal of 1195 was home to a huge debate about whether Hibernia needed reform to be more traditional, in the manner of Stonehenge, and whether a Tribunal should have the autonomy to set its own Peripheral Code. The parens of the paprentices who, in their macgnimartha, had attacked Damisona, were convicted only of a Low Crime, outraging the Stonehenge magi. This led to much more travel and visiting of Hibernia by other magi, as well as more appeals ot Magvillus from magi who felt the Irish Quaesitores had been unfair. The covenant of Elk's Run was founded in the aftermath. Meanwhile, in 1209, the maga Swan of Ghent was killed during the Black Monday massacre of Dublin, when Ua Broin raiders killed several English settlers.

In 1213, the magus Holzner of Tytalus, a German magus, joined the covenant Praesis. He then tried to steal its cathach and flee, but was slain by his sodales. (More on cathach later.) His outraged parens, Ballack, left the Rhine for Hibernia, laying siege to Praesis. Many Irish magi saw this as a clear case of foreign aggression, but by convention of the Tribunal, few interfered. The Siege of Praesis lasted a full year, preventing many of its members from attending the Tribunal of 1214, and straining relations between the Hibernian magi and outsiders. Praesis fell, and peace was restored, but it is still an uneasy peace.

The English lords are increasingly asserting their authority and adopting Irish ways, despite the wishes of the English crown. The Irish kings chafe under foreign rule, outside of Connacht. The Hibernian magi, likewise, face tensions from outside. However, peaceful visits, trading and tolerance still exist, and the Hibernian magi see themselves as loyal to the Order. Not ever foreign magus is hated, feared or suspected, and there may yet be peace if both sides can overcome their fears and misunderstandings.

So, what are the Irish like? The basic social framework of Ireland is the clan - an extended group of people claiming descent from one heroic forefather. The English have imposed their own style of French feudalism on top of the Irish society, but their attempt to force it is failing. They aren't replacing Irish culture - rather, they are adopting it, becoming more Irish than the Irish.

Ireland is shaped roughly like a bowl, with a ring of low coastal mountains surrounding plains and forests full of rivers and lakes. The climate is warmer and wetter than England, with only rare snowfall that never lasts long. Rain is plentiful, especially in the west, and some say it rains three days of every five. Flooding is a big problem, and heavy rains can threaten early plantings. The Irish divide the land into cantreds, administrative areas controlled by a clean leader. The English have grouped several cantreds together as liberties, inheritable feudal properties, and shires, cities and their nearby land which belongs to the king. The lord of a liberty has more independence than the lord of a shire, who is after all just the king's agent. A lord of a liberty keeps their land-rents and taxes, while the shire-lords give much of that to the king. On the other hand, more money passes through a city than rural area, so shire lords are often wealthier.

Prosperity, rank and honor are measured in cattle. Cattle raising and thieving are the cornerstone of IRish society. LArge herds need large pastures and must move often. Grass grows year round, of course, but relocation prevents overgrazing. Summer pastures are higher, farther from home, while winter pastures are closer. Because of the many wolves of Ireland, farmers build roofed, fenced areas known as byres to keep cows safe at night. Sometimes, a small byre is attached to a house, but usually it's a standalone. Nobles and honorable farmers are expected to keep a number of cows appropriate to their station. If the herd gets smaller, their standing falls, which makes cattle raiders dangerous to both herd and honor. Cattle are branded to identify their honor, but even so, retrieving stolen cows from a powerful foe is hard. A man's responsible for his herd and any losses from it. Success in reclaiming stolen cattle depends on power and allies.

Besides cattle, farming provides some of what a farmer makes. Primarily, that's oats, then wheat and rye. Because clans move often, fields are temporary and usually unfenced. A plot will usually only give two harvests before it's abandoned or ruined by cattle and spring rain. Cows graze freely, and legally have the right to walk through a field of crops if water is on the other side. A land-owner who blocks cows from water is a criminal. Most of the Irish interior is forested, with apple, hazel and oak trees providing food and fuel. The forests are full of animals - boar, fox, badger, wolf, deer, hare and squirrel. Cattle can also be found in the woods, but they're poor grazing, and wild cattle are rare. Outlaws and fgiannai live in the woods. A fian, you see, is a band of young aristocrats who go into exile while awaiting land inheritance. They are seen positively as future warriors who must prove themselves to their clan by surviving outside it . Outlaws are legal outcasts, denied aid by all. With the recent English invasion, many outlaws' only crime was owning land the English wanted. Such men are heroes to their neighbors, and the outlaws will be trouble in the coming years.

IRish society is centered on the clan, whose basic social unit is the tuath, which means 'people' but includes the clan's native territory, its free clients, unfree clients and slaves. Tuatha are named for a hero-ancestor, and most originated in the fourth or fifth centuries. New tuatha appear when a powerful leader seperates from the previous one to form a new clan, while weak tuatha disappear when destroyed or absorbed by a greater tuath. As of 1220, there are about 125 tuatha. The most powerful are the "five bloods": the Ua Neill of Ulster, the Mael Sechnaill of Meath, the Ua Conchobair of Connacht, the Mac Murchadha of Leinster and the Ua Briain of Munster.

The Irish divide themselves between the daorcheile, those without honor, and the grad flatha, those with it. The daorcheile are peasants, whether they're slaves, unfree farmers or free farmers who barely own enough to survive. The grad flatha are wealthy free farmers, nobles, priests, monks, professional judges, doctors and poets. Most social standing is hereditary, but personal honor does play a significant role. Every free man has an honor-price, an eraic, which is the amount payable in compensation if they are socially or physically injured. This is paid in cows, and it can grow and shrink depending on your fortunes. Besides physical harm, damage to reputation, social connections and property demand payment, with prices set by the type of injury. A verbal slight might merit a significant chunk of a man's eraic, while murder would pay the full amount.

Most people are daorcheile. Slaves are taken in raids, though that's rare these days. Unfree farmers, or bothach, get a cow and a small plot of land in exchange for their labor, with interest so high it can never be repaid. A free farmer or boaire is also a client, but has a better interest rate, one that can eventually be paid off. The terms a lord offers, determining whether a farmer is free or not, are hereditary. The grad flatha have many ranks - lesser nobles who have the minimum number of client boaire, cattle lords and greater nobles. The most important nobles of a clan are the derbfine, those within four generations of the current chief. Each clan has a chief or king, the ri. The king of a single tuath is a ri tuaithe. One who holds several other tuatha as clients is a fuirig, or over-king. A king of over-kings is a ri ruirech, and a king of one of the five provinces is a ri caicid, a provincial king. The grad flatha also includes the professional learned classes - judges, poets and doctors. Many of those jobs are hereditary, with only a few families doing the job for a tuath. All posts require intensive training, roughly equivalent to the academic career of continental university teachers. The kings of the more powerful tuatha appoint an ollamh of each position, the titular head of that class within the tuath.

Every tuath holds public assembles, oireacht, which meet at a specific location at set times each year to determine clan business. Assemblies often settle disputes, levy fines, collect taxes and, if needed, select new kings. The candidate must be of the derbfine of the last king, making everyone with a common great grandfather eligible. Sometimes, the derbfine chooses a successor before a king dies. Such a person is known as a tanaise rig, but having such an heir doesn't always stop dynastic struggles for power. A king is crowned in a sacred ceremony in which he symbolically marries the tribal lands. In some tuatha, this means literally marrying a local faerie woman, a sort of Tuatha De land goddess. The ceremony is highly ritualized and involves the king swearing to abide by the laws and gods of his people, to do no harm and to universally share the king's truth of legal and moral judgement.

Only 5% of IRish marriages happen in church - most are secular, solely requiring a couple to declare their intention to marry. Once that's done, the marriage is legal. The Church disagrees, but most Irish prests participate in it rather than preventing the practice, ignoring the 12th century reforms. Easy marriage means easy divorce and easy remarriage. The nobles are the worst offenders, marrying and divorcing as they please. Some men even have many wives at once, but that custom is fading. This loose view towards marriage allows a clan to grow very quickly - one Ua Donnell chief has 18 sons by 10 wives and 30 grandsons. There are other differences in Irish marriage that annoy the Church, Irish can marry first cousins, while canon law dictates three degrees of separation between partners. All of a man's legitimate sons can inherit, without care for birth order or even whether a wife is divorced, so long as the mother is not a slave. A wife does not bring dowry, but instead the groom pays her family a bride-gift. Lastly, an Irish marriage does not grant an alliance btween groups - or even stop aggression between in-laws. Marriage doesn't sotp or hinder conflict between a man and his brother-in-law, and the Irish men don't expect their wives' kin to follow them into battle.

Hostages are a common practice - noble sons given to a king to ensure a tuath's good behavior. The hostages live as part of the king's retinue. If the agreement between tuath and king is broken, their lives are forfeit. Since the hostages can be related to the king, and often are, the king may have sentimental reasons for not killing them, even so. Fosterage is common among the nobility, too - at age 7, noble sons and daughters leave home and live with foster parents. Boys stay until 17, while girls only until 14. Fostered children form emotional ties as strong as those with their parents. In all legal matters except inheritance, a foster son is as legitimate as a biological son, and a man can expect his foster sons to follow him into battle. Cuddy, the anglicized from of the Irish curd Oidhche ('a night's portion'), is the entertainment and feast a client owes his lord. One of the king's privileges is the right to travel through the tuath and feast at the nobles' houses. Most clients cannot refuse this, and several clients have bemoaned a gluttonous king. Poor nobles must borrow from their neighbors to provide the king's cuddy.

Ireland is full of villages, or rath - ringfots with wooden walls surrounding some huts. The larger and more powerful a clan is, the bigger the rath. Unlike a continental village, a rath is mobile, as the clan can quickly uproot and shift to a new location. Raths are not built on rivers or roads, but tucked away in secure areas. Small coastal ports do exist, but most of the Irish live in the interior. Christianity did change the raths some - instead of surrounding a chief's hut and his clients, the walls can surround a monastery, the monks and their lay supporters, the tradesmen and herders who supply the community. Monastic raths are self-sufficient and so found in the interior, with no need for coastal or river trade. Walls made of piled stone surround a stone church and tower, as well as several wooden huts used by the community's supporters.

The Ostmen brought cities to IReland. Originally, these longphorts were enclosed winter camps, but they became homes. Once the raiding ended, which coincided with the Irish adopting and learning to use Ostman weapons, the two groups lived in uneasy peace. The five cities of the Ostmen, Dublin, Waterford, Wexford, Cork and Limerick, remain home to them. Ireland has over a thousand raths, and the more powerful ones have stone walls. Religious centers, such as Armagh, Cashel, Kildare, Tuam and Dublin, as well as royal residences, use stone. They have given up mobility for a stronger, more permanent defense.

Next Time: More about the Irish.

Ireland is History

Original SA post Ars Magica: The Contested IsleThe Irish year is divided into two seasons, not four. (Socially. Ruleswise, still four.) Winter begins on Samhain, November 1. Summer starts on Bealtaine, May 1. Samhain is the end of the harvest season and the start of the dark half of the year. On Oiche Shamhna, the Night of November - that is, October 31 - the ghosts and faeries stalk the night, and the Tuatha De Danann move to their winter palaces, disrupting others. Bealtaine is the start of the planting season and the light half of the year, full of celebrations and cheer. Equally important are the celebrations of Lughnasa on August 1 and Oimelg on February 1, more commonly known as the Feast of Saint Brighid. Lughnasa is the harvest festival, celebrated on the closest Sunday to August 1.

While these pagan elements are retained and valued by the Irish, they are thoroughly Christian, not pagan. Christmas and Easter are the most vital holidays of the year - to the point that the rising sun on Easter seems to dance, increasing the piety of all that view it for the rest of the week. On Christmas eve, candles are lit to guide travelers, and at midnight on Christmas, all the animals of Ireland gain the power of speech until the sun rises. Hearing an animal speak is very unlucky, it is said, so most people stay inside.

Poets and musicians are extremely prestigious jobs in Ireland. They are beloved by both the Irish natives and the English conquerors, moving easily between the two groups. Currently, love songs are greatly in fashion. A good poet, meanwhile, must memorized hundreds of tales to earn their title, and so they always know an appropriate story for any occasion. Hurling is a popular sport among the Irish youth of all classes - it is a game in which a wooden stick, the hurley or caman, is used to drive a brass ball. One team tries to move it towards a goal while the other defends the goal. Hurling is also popular in Scotland. It is a dangerous game, with frequent injuries and even some deaths. The faeries love the sport, and a good hurling player may well be abducted and forced to play hurling with them all night long. Rules are provided for hurling: specifically, it's an Athletics roll, and if a match becomes violent, a hurley has the same stats as a club. The Irish also enjoy horse racing - riderless, as in Scandinavia - and a type of chess known as fidhcheall, as well as backgammon (known as tdiplis) which is more popular among the English lords.

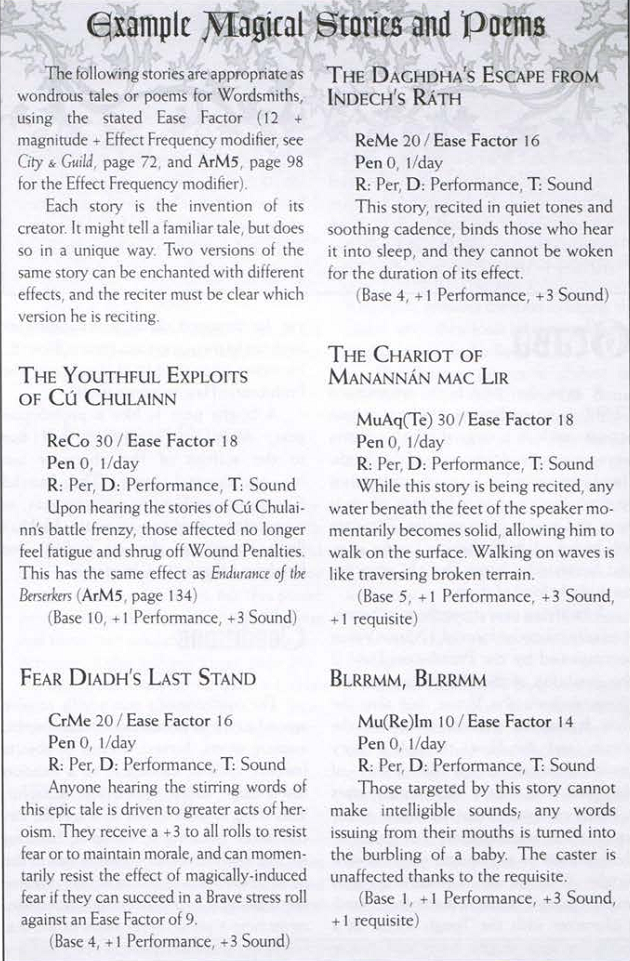

Performance magic is not rare in Ireland, both among magi and hedge wizards. Poets and musicians can go anywhere, and so they can be excellent spies - plus, most listeners will have no defense against sorcerous music. Hedge wizards who practice performance magic tend to use it to earn money and advance their clan politically. OFten, this leads to conflict with the English and bloodshed. A magus must be more careful - the native poets don't like having their role usurped, and the Order cracks down on too much mundane interference.

So, what of the English? Their ideas of power and political might are different than those of the Irish natives. English value land, Irish value cattle. Before the coming of the English, Irish would steal cattle but not land. Tuatha moved under pressure, but land grabs were never the goal. The English, however, want land, and their stone towers make it clear they won't be leaving any time soon. Irish sons inherit equally, via complex arrangements. They work the land and herds together for five years until a separation can be made, with shares distributed by the youngest son. The English practice primogeniture, with the eldest son taking all. An Englishman with an Irish wife often assumes he'll inherit her father's title and property, but her kinfolk will disagree. Royal succession is also different - the English kings follow primogeniture, as with other property. The Irish have no such guarantee - everything rests on the derbfine decision. Plus, in Ireland, a higher king has no authority over a lower king's rule - a fuirig cannot reverse the decisions of their client ri tuaithe, while an English king can easily reverse every lord under them.

The Irish have four languages in use today - English, French, Gaelic and West Norse. Gaelic is the native tongue, shared with Man, the Kingdom of the Isles and Scotland. Each province save Meath speaks its own dialect. The Finn-Gaill of Dublin (that is, the 'white foreigners') have adopted Leinster Gaelic, but the Dubh-Gaill ('black foreigners') of Wexford, Limerick, Waterford and Cork speak West Norse still. The lords of the Norman occupation speak French, while their servants prefer English. The educated, of course, speak Latin.

So, let's talk about the Hermetic culture. Hibernia's contradictory. It is old, but newly rediscovered. It is conservative, yet very strange to outsiders. It allows easy conflict between magi but protects hedge wizards. The most obvious divide is between the Irish native magi and the new arrivals, of course. Hibernia has grown away from the rest of the Order for years, developing its own culture. Newcomers see these ways as outdated, nonsensical and often undignified. Were there more land, the two sides might get along better, but Ireland is not a big place.

The generations-old Irish covenant Praesis has fallen, besieged in a year-long Wizard's War and finally felled by betrayal. Behind this battle was the conflict of Hibernia's Tribunal: land must be protected and challenged. Covenants are not the sum of their members, but the result of ancient and powerful artifacts chosen as symbols. The standing of magi is not based on learning, but their ability to protect their own. Any magus unable to protect their land is unworthy of it. That is fundamental to the Order in Ireland, and is the means by which outsider magi have gained a foothold, earning their share of riches. The siege of Praesis was mostly between the ORdo Hiberniae, as the Irish magi name themselves, and the continentals, as they name the English. However, not all of Praesis' attackers were foreign. Some were Irish, using the conflict to rail against centuries of restrictive traditions - an increasingly common attitude among young magi. And while it fell, the siege of Praesis continues to be a pivotal point in Hibernian politics. If, as they did at Praesis, the Ordo Hiberniae lose control of the Tribunal, centuries of tradition may be overturned in a single generation. There are two factions, then, vying for control of the Tribunal - both politically, and among wilder magi, more directly.

Ireland is a land where history is known to go in cycles. This isn't mere lore - it's truth. The Treaty of Cnoc Maol Reidh is centuries old, an agreement between the Order and the native hedge wizards that irrevocably grants Connacht to the hedge wizards as their own land. When the Order took hold of Ireland, the druids were pushed aside, granted the land to seal the peace. This was just as the Fomorach were driven to the north, the Fir Bolg to the west and the Tuatha De Danann underground. Some believe the Ordo Hiberniae, likewise, will be forced to retreat to Connacht, leaving the island to the continental magi - it can already be seen in the English conquest.

Most older Irish magi view the English with suspicion and concern, but the younger magi, especially those in their macgnimartha, have heard the English message and embraced the idea that no part of Ireland should be denied them, that the treaties are outdated and should be annulled. Most of the English magi find the Irish to be backwards and strange. Most know the old tales of Ireland as too dominated by faerie power to be much use, but nothing recent until around 1170. House Tremere were the first take note - the archaic, dangerous and strange traditions were at odds with good Hermetic governance, they felt, and that could not be allowed. While they are called 'English' for the first Stonehenge magi to come, the continental magi come from all over, initially supported by House Tremere, to claim new territory over the last fifty years.

Why so keen to reform now when previous efforts have failed? Firstly, while the protections of hedge wizards are legal, they seem to set the natives on par with magi, which is improper to many. Secondly, the continental magi are now settling in Hibernia, clinging still to their own views on the Code. In their own way, they're as conservative and change-resistant as the natives. The English prefer the normal practices: harvest vis, intimidate hedge wizards and ignore those that aren't useful. Connacht, to them, is land ripe for taking. However, they've been here fifty years now. Some have raised apprentices in Ireland. While these apprentices were denied macgnimartha and still see themselves as different from the natives, by the next generation, the distinctions may fade.

Violence is common in Hibernia. Wizard's War is easily declared, certamen frequent and grog raids similarly common. Most covenants own resources that lie outside their legally protected territory; such resources are always at risk, though the Hibernian magi do take the Code seriously. Battle is to assert dominance, not kill, which is why certamen is so common. Grogs, well...grogs die a lot. There is, however, an understanding that things will find their own level. The threat of violence is real, but often the best ward against it is to be a good neighbor. The Peripheral Code doesn't mandate this, but those who break the unspoken rules often regret it.

So, what exactly is a macgnimartha? It means 'youthful exploits' and it refers to a brief period between apprenticeship and becoming a magus. In this period, the apprentice leaves their parens and covenant and spends a year or more unprotected and unsupported. They have sworn no Oath, have no Parma Magica and are outside Hermetic law. Most test their power against faeries, some against mundanes and others against Hermetic targets. In the last case, stolen magic items are usually ransomed back. Magi of Hibernia all remember their own macgnimarthas, and rarely treat those in one harshly. Importantly, the Treaty of Cnoc Maol Reidh makes no mention of macgnimartha, and the youth often head to Connacht for their sport or fortune. For most apprentices, the macgnimartha lasts a year, or "until his beard encircles his chin," at which point they swear the Oath and are taught the final secret of the Parma. Their character and reputation are judged by their deeds in macgnimartha. Despite social pressure, since failing to take a macgnimartha can reflect badly on the parens, not all apprentices undertake it. Some instead go to Leth Moga, where they are given security, lodging and use of the library in return for assisting others and copying books.

What makes Wizard's War different in Hibernia? Well, the declaration. The formal declaration must be given in person before witnesses, but not necessarily directly to the target. It must be public, of course, and Wizard's Wars have been declared invalid if the magi involved took steps to keep the target from finding out. But there is no warning letter, and while the formal declaration must still be made one month in advance, it's common for the target to find out some ways into that month and have less time to prepare. A magus may also declare Wizard's War against multiple foes by naming them in the formal declaration, which can draw allies in on both sides. You can declare war on 'all who hold to the Gae Bolg,' for example. Hibernia's Code does not require months of break in a war, so many magi extend the war as soon as it begins - indeed, the Peripheral Code assumes that Wizard's War is extended unless there is positive evidence that it wasn't, so a War typically lasts until the death of one side, a surrender or a treaty. In practice, they tend to devolve into raiding and theft until one side calls a truce. Grogs and mercenaries are often used as proxies, so it's typically more about submission than murder. Famously, a state of war continues to exist between the magi Grainne inghean Uaitear of Vigil and Cu Chonnacht Cluasach Mac Tire, despite the fact that they've met several times while the War has been on. The Siege of Praesis, however, was the first extended Wizard's War most English magi had seen. Given the results ('Praesis fell to them'), opinions are mixed on whether the law should be formally challenged.

Certamen, now. The polite rules of Certamen that are so common on the continent do not apply here. The aggressor picks the Technique, the defender the Form, but neither has right to veto and there are no social norms about who can challenge when or how often. Certamen is often fought over resources outside protected lands, or between magi before things escalate to Wizard's War. The usual social stigma about refusal to fight is especially strong in Ireland, but there is no stigma against using vis in certamen matches.

Next Time: Responsibility of the Order

Ireland is Hermetic

Original SA post Ars Magica: The Contested Isle

The Order of Hermes assumes the ultimate supernatural authority in Ireland, claiming the right to act against those who break convention and flout their power to cause chaos. Even the elder races listen when the magi speak. The Order does have a history of respecting the Treaty of Cnoc Maol Reidh, allowing the Coill Tri to manage their own lands, but they are ready to punish magical beasts that terrorize villages or faeries that prey on travelers...and unless a hedge wizard's own tradition acts first, the Order is willing to punish them, too.

Hibernian philosophy holds that a coven of witches is not really that much less than a covenant of Bonisagus. It is by deeds that worth is measured, they say. The Order in Ireland feels a responsibility to maintain the old ways. This is not a cover for pagan sympathies at all - rather, it refers to the non-Latin forms of magic found in Ireland before the Order came, dating sometimes back to Nemed and Partholon. These were precursors to the Houses of Hermes - shapeshifting druids, faerie dealers and enchanters. If the Order forced them to join, those ways would be lost, or at least diluted. The Hibernians claim any threat they might post has been neutered by confining most hedge wizards to Connacht.

Magic and Faerie auras are precious in Ireland, for they are often tied to important historic events. Magi there feel a responsibility to these places and to caring for them. This can force them into conflict with mundanes, and in those cases, the Tribunal favors a strong show of authority. Protecting an aura from mundanes is not considered interference. Outside Hibernia, vis is often harvested as soon as it appears, then hoarded. In Hibernia, this practice is considered to be at odds with good husbandry of magic, and vis is typically left unharvested untul it is needed. Magi typically store only small amounts of vis, mostly gained by trade or luck, and visit their vis sources frequently to gather waht is needed at the moment. Many sources are turned into casting spaces for rituals, and Irish magi often use vis that has not been moved out of its original form. Since most sources have vis available all year, though, they make attractive targets for raids or hungry beasts. Traditionalists of Ireland see this as just a risk to be managed, much as mundane farmers must guard their crops. Extracting vis from auras is seen as detrimental and against the principles of responsibility. Fortunately, Hibernia has many vis sources, so few magi feel the need to break tradition there, or to steal vis from others.

In Hibernia, magical beings able to talk are considered equal to humans and are given a voice at the Tribunal. This status means no covenant may molest these creatures or take anything from their territory without permission or at least tribute in kind. However, even the Irish are a bit lax in this regard, and the strength of nearby magi and covenants tends to impose itself on the power dynamics of the magical and faerie beings nearby.

Hermetic literature in Ireland is still predominantly in Latin, but thanks to the influence of the Irish Church, the use of vernacular Irish is increasing and can be found in the marginalia of many Hermetic texts. The Ordo Hiberniae are very fond of chronicling the lives of important magi and historic figures, and they often produce texts detailing them. Continental magi tend to view these as a distraction from study of the Arts or creating spells. In fact, they tend to find Irish books on Hermetic theory dull and overcomplicated, much as their mundane counterparts view Irish histories, as they tend to dwell on minutiae over practical application.

The continental magi tend to be annoyed by many things the Irish take for granted. They find Irish vellum to be greasy and unsuitable, and some even import parchment. They complain of oversalty food and even bring in foreign cooks. The Irish often practice beekeeping, and the trading of honey is a tradition among Irish magi, as each covenant has a unique flavor. Continental magi find this twee and undignified, but many Irish take great pride in it. The Irish magi tend to refer to House Ex Miscellanea as 'the Younger House,' and while this is accepted by Irish Ex Miscellanea, continental Ex Miscellanea find it insulting and grating. Finally, it's usually easy to tell the two factions apart by their outfits. Ordo Hiberniae often wear mantles of patchwork colors or pattern to denote status; apprentices wear plain, single-color cloaks and those in macgnimartha wear three colors, magi wear five and the Tribunal praeco wears seven, and the heads of covenants can wear six. This has not yet caught on among continental magi, who generally follow foreign fashions.

And now, let's talk treaties. Treaties record agreements between covenants or any other supernatural group. Most Hibernian law is made of specific treaties for specific people and cases rather than general precedent. This makes it dense, counterintuitive and cumbersome - rulings don't provide precendents all the time, even when the same elements are involved, and the English magi find this untenable. They want change. In many ways, the treaty system mirrors the Brehon Laws.

A treaty can be made between any individuals who have the right to be heard at Tribunal. This includes magi, covenants, the Order of Hermes itself, the Tuatha De Danann, the Coill Tri and so on. A treaty can be temporary or permanent, or have conditions within it that release the parties involved from it. It's the job of the parties on either side of a case to come to an agreement, with Quaesitorial aid, and the Tribunal's role is to ensure that neither side breaks it. No treaty can break the Peripheral Code or bind a magus to actions that would break the Oath of Hermes.

Now, covenants. The Order requires any magus to be resident of the Tribunal to be able to vote. In Hibernia, this means belonging to a recognized covenant. Those outside a covenant are considered vagrant and risk exile, no matter how long they've lived on Irish soil. However, any magus can found a covenant, so long as they have land, wealth and a trophy - a cathach. The land must be any space upon which to build a home that the magus has protected for one full year. For historical reasons, wealth means cattle, so covenants must have cattle. The cathach, meanwhile, is an item or relic of some significance to the covenant, which must be displayed at Tribunal to identify the covenant.

A cathach must meet certain conditions. First, it must be a magical treasure - not necessarily a Hermetic treasure or even of the Magic ream, but it must trigger a positive response to magical identification. Second, a cathach must be taken, not made by the claimant magi. It might be taken from the land, from the magic realm or from another magus or covenant. The nature of its acquisition is important, for it becomes part of the story of the cathach and the character of the covenant. Third, the cathach must be significant. It must have a story behind it - either it is of legend or it was made by a legendary or noted figure. Last, it must be displayed. It must be brought to Tribunal to prove residency and, when not at Tribunal, must be kept outside the Aegis of the Hearth.

If a magus can hold those three symbols - land, wealth and cathach - and support themselves for one year, they have the right to represent themself at Tribunal. Other magi may attempt to seize the cathach before the year is out, and if succesful, the covenant may not legally form. The raiders must abide by the Code and may not harm resident magi outside a Wizard's War. However, any magus caught in possession of a cathach claimed by another forfeits immunity, as if they had entered a sanctum. Cattle are similarly protected, though they may be kept within the Aegis. This calls back to the earliest days of the Order in Ireland, when the four magi of Circulus Ruber made their vow to defend their land for a year if need be, along with its treasures.

Once a covenant has defended its cathach, land and cattle for ayear, it may petition the praeco for recognition and to have its name and lands recorded at the Mercer House of Leth Moga. From then on, they receive Redcap visits. A covenant's lands are defined by its vis sources, consisting of all sources that a magus may encircle between sunrise and sunset, without any spells or enchanted items to speed progress. These sources are protected by law, and any magus raiding them is committing the crime of depriving another of magical power. Sources claimed outside this legal boundary have no such protection, and for this reason covenants mark their sources with their symbol. No magus outside a covenant can claim Hibernian residency, and only those who prove residence can vote. Covenants that attend Tribunal without a cathach have failed to prove residency for their magi.

It can be tempting, and has been known, for younger magi to live outside a covenant. They have no cathach to protect, after all, and votes matter only once every seven years. Such a group, though, has no voice, no official Redcap visits and no legally defended property. Hibernia does not recognize chapter houses or vassal covenants. If a magus no longer wants to live in their covenant, they must enter or found another, or else forgo legal protection. Despite the obvious vulnerabilities, there are still many independent magi, with representatives from almost all Houses. In order to vote, they must produce a cathach, though, and must show that they havel and cattle. In all respects, they must found a covenant of one.

Next Time: Views on the Code.

Ireland is Tribunal

Original SA post Ars Magica: The Contested IsleSo, how do the Hibernians view the core of the Code of Hermes? Well, let's look at the clauses. The Deprivation of Magical Power clause is interpreted to apply only to those resources within claimed land protected by a covenant. Any resources outside that boundary are free game. You can put your marker on them, but you'll have to defend them yourself, not with law. The Slaying of Magi and Wizard's War clauses are taken as normal - any murder outside Wizard's War is a high crime. Forfeit immunity happens when you try to kidnap an apprentice, steal a cathach, enter a sanctum, assault a familiar or raid legally protected vis. We've already talked about how Wizard's War must be declared in Ireland.

The clause on abiding by Tribunal decisions is standard, though they have their own interpretation of what 'reasonable interpretation of the Code' means for purposes of overriding a Presiding Quaesitor's veto. The voting rights clause - well, any magus who can prove residence with a cathach has a vote, which they can give as proxy to others as normal. Hibernia also recognizes the votes of appointed supernatural ambassadors from the supernatural realms and ancient races. These votes have exactly as much weight as anyone else's. The Mundane Interference clause is taken with a Transitionalist view, since in such a small Tribunal with such a small population, where many magi will have familial ties...well, association with mundanes is inevitable. Ireland's kings have a history of going to druids for aid, and magi have been counted among them sometimes. Charges of interference require that the Order must be shown to have been endangered as a result.

Scrying, now, the scrying clause is also one that requires a lot of evidence. Without clear evidence of scrying detected by a "trustworthy person," the Tribunal requires that any information learned must have been impossible to gain by mundane means. Thus, most magi accept that some scrying is inevitable and prefer to settle things more directly than via complaints at Tribunal. The apprentice clause is taken not to apply to those in their macgnimartha - they are no longer their parens' responsibility. Bonisagus retains its traditional privilege, but any Bonisagus claiming an apprentice must do so either when they are first presented by the Coill Tri or their parens or at a subsequent Tribunal before the macgnimartha - so no stealing apprentices between Tribunals.

While the Casting Out clause exists, Hibernia prefers exile to casting a magus out of House or Order. An exiled magus must leave Hibernia under threat of Wizard's March. Exiles may petition to return, but must find a resident magus to stand for them and plead their case, which is then given to vote. The Enemies and Allies clause is taken to define all elder races of Ireland as allies - the Fomorach, the Tuathe De Danann and the Fir Bolg. The Coill Tri is also defined as allies of the Order by the Treaty of Cnoc Maol Reidh. This provides protection - an ally of the Order must be given the same warning as a magus of any Wizard's War.

Beyond that, hedge wizards in Ireland are generally considered allies of the Order. The protections this offers are not absolute, however. They may legally own a single vis source, and while they may use others, these others are not protected. House Mercere must take messages to the Coill Tri as they would any covenant, but individual hedge wizards only sometimes receive visits, and that's not official or required. A hedge wizard has the right to join a covenant, which in principle gives greater protection, but in practice they are expected to join House Ex Miscellanea and the Order. Wizard's War must be declared on hedge wizards before attacking them, as with magi, and slaying a hedge wizard outside a War is the crime of assaulting allies of the Order. Magi who declare Wizard's War on 'all hedge wizards' - which is legal in Ireland - are traditionally persuaded to allow their Wars to lapse. So far, no English magus has made such a declaration.

Any magus caught in possession of a cathach is treated as if they have invaded a sanctum. A thief must protect a cathach for a full year from all aggression if they plan to claim a covenant's resources. It'd be possible to disenfranchise a covenant by stealing its cathach and denying its magi votes at Tribunal, but doing so would risk making the Tribunal inquorate. Of course, few magi want to see the Siege of Praesis repeated across Ireland. Still, it's a foolish covenant that leaves a cathach undefended. Sure, they can't be in the Aegis, but many covenants make pacts with faeries or beasts to defend the cathach. It is tradition in Hibernia to live and let live, for the most part - the best protection against aggression is to not be so aggressive yourself.

Much as mundane Irish justice does not often kill, Hibernia rarely uses the Wizard's March or the destruction of either familiar or talisman as punishments. Compensation for damages and correction of errancy is the focus, and fines, obligations and restrictions are common, with exile as the highest punishment. Fines of vis outright are rare, however, and instead access to vis sources tends to be granted to the wounded party for a set period. Only one crime in all of Ireland is punished by March: trafficking with demons. Still, on the rare times that the clause of the Oath that requires execution is invoked, it is taken deadly seriously - though Hibernian justice does not pursue off the island, as a rule. Those who flee justice are considered exiled and, unless they return by the next Tribunal, will be cast out of the Order. In practice, however, no one tells anyone outside Ireland when this happens...but Irish memories are long, so if you flee, don't come back. There are few hoplites in Ireland, as it is expected that all covenants can defend themselves and will offer that strength when needed by the Tribunal.

The Irish work hard to maintain good relations with the magical and mundane beings of Ireland, and any magical beast that threatens that peace is punished by the Order. There is no set punishment, but faeries have been clapped in irons and magical beasts have been forced out of their homes or pressed into service. Enforced binding into servitude is the ultimate punishment, invoked only once in the past - there are lab texts for magic bridles, yokes and rings to command obedience, but no one is keen to see that incident repeated, though the threat is there.

When the Coill Tri break their agreements or obligations, they must make good to the Tribunal. The Order retains authority over Connacht, even if it does not enter it. As there is no Code for the Coill Tri, each case is judged on its merits. Those who displease the Order are forced to serve or give tribute in vis each season for a year, are banned from certain regions or given other punishments fitted to the crime.

The Hibernian Tribunal meets at Cnoc na Teamhrach, the Hill of Tara, in Meath, which is home to the Lia Fail. Traditionally, Circulus Ruber makes all arrangements, including the spells needed to raise a temporary settlement. Before the Tribunal proper, embassies from the hedge wizards, faerie factions and magical creatures meet with magi to discuss things, in what is known as the Sacred Council. The Praeco and Presiding Quaesitor both attend, and other magi attend by invitation. All supernatural beings of Ireland may attend, and it is here that their ambassadors for the Tribunal are chosen. The Tribunal is always opened with a prayer from the Holy Tradition of the Celi De; currently, the role is filled by the magus Indrectach. The Tribunal typically lasts seven days and nights and closes with another prayer. Official business is in Latin, but Irish is commonly spoken casually. Weather is kept good by magic and food is provided.

While every recognized supernatural group may send an ambassador, the Infernal has never tested this right so far as anyone is aware. The Coill Tri choose their own ambassador from among their number, to speak for all hedge wizards in Ireland - including those who are unaware of it. This ambassador is responsible for ensuring the duties of the Coill Tri are met, and to handle issues dealing with hedge wizards. The role is not easy, and generally no one trusts the Coill Tri ambassador, including the Coill Tri. The English magi hold their own pre-Tribunal council to reach consensus on key issues, usually about Code reform, though the aggression of the covenant na Lam Baird is also a concern these days. Consensus isn't easy to get, and the council needs strong leaders. They do not choose an ambassador, as they are magi and can all attend and vote.

The Tuatha De Danann choose their ambassador at the Sacred Council, while the Fomorach and Fir Bolg always send ambassadors from their royal lines. Faeries outside the Tuatha De can send an ambassador, and if they don't, House Merinita will select a representative for them at the Sacred Council. Magical beasts that can speak human language may also select an ambassador from their ranks. If they don't, a magus of the Order speaks for them. Individuals other than the ambassadors may not enter formal treaties except via the ambassador.

Currently, the ambassadors of the Hibernian Tribunal are as follows. Fothaid, a younger son of the Fir Bolg King, who is an impressive figure - seven feet tall, muscular, graceful, eloquent and handsome. He is exceptionally vain about his pure royal blood and will enter a rage at the suggestion that he is less than perfect. He cares little about the Fir Bolg and tends to use the Tribunal to gain admirers. King Madan Muinreamhair of Tir Fhomoraig has sent his ugliest relative, Aimid, to represant the Fomorach. Aimid's face is pustulent, her arms mismatched, her feet unable to be shod and with nails like horn. She never tries to hide her deformities and enjoys the reaction they provoke in humans. Few have ever gotten to know her closely, but she is in fact a very shrewd and canny politician. She is carried on a bier by four Fir Bolg slaves to prevent her from touching Irish soil.

Until two Tribunals ago, the magical beasts were represented by a fiorlair, a 'true mare,' until an English magus crassly asked her to be his familiar, which she took to be some form of magical servitude. She resigned her post in disgust, and it has been taken by the King of the Eagles, who claims lordship over all birds in Ireland, though whether this is legitimate is unknown. The deal that brought him to Tribunal was brokered by Cliodna of Lambaird. The Tuatha De Danann are generally represented by the faerie Mug Ruith, who styles himself after a famous Munster druid that studied under Simon Magus in Jerusalem. Mug Ruith is the court magician of the Munster kings, and some say he was the executioner of John the Baptist, forever cursing the Irish with violence. Mug Ruith currently served Bobd, the king of Munster's Tuatha De, by joining the Sacred Council every seven years, arriving with his flying machine, the roth ramach ('oared wheel'), a bull hide and a bird mask. Mug Ruith is known to live on Dairbhre Isle, off the western coast of Desmond. He owns many magical items, including a chariot, a shield and a stone that at one point could change into a poisonous eel but seems no longer capable of doing so. He lives with his faerie daughter, Tlachtga, who is also a potent druid.

Next Time: Connacht

Ireland is Clanny

Original SA post Ars Magica: The Contested IsleThere are a number of clans in Connacht, as well as the Coill Tri and the Fir Bolg. The Connachta clans claim descent from Conn Cetchathach, Conn of the Hundred Battles, and are cousins to the Ui Neill dynasty. They have ruled Connacht unchallenged for centuries despite deep-seated rivalries. The Ui Briuin rose to power five hundred years ago due to friendship with the druids. Their major septs include the Ui Briuin Breifne, who rule the Kingdom of Breifne, who include the Ui Ruairc and Ui Raghallaigh families, and the Ui Briuin Ai, rulers of Connacht, who include the ruling Ui Conchobair family. The Ui Fiachrach were once the dominant clan of Connacht, but lost to the Ui Briuin. Still, their old songs tell of the time when they ruled. Their families include the O Cleirigh and the O Sheachnasaigh. The Ui Maine drove the Fir Bolg west when they took the lands near Sionainne. Their influence has weakened over the centuries, and the Fir Bolg still hate them for it. Their families include the O Ceallaigh, the O Domhnallain and the O Fallamhain.

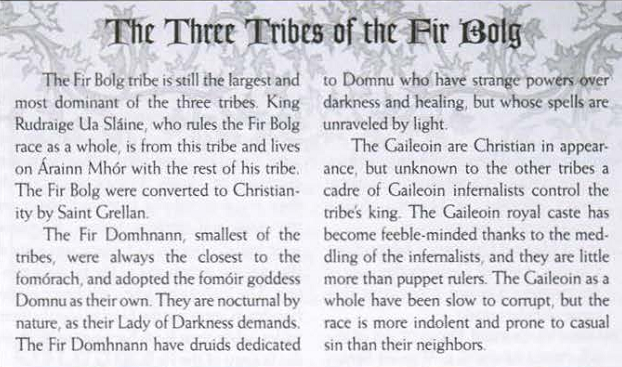

The Fir Bolg retreated to Connacht after their defeat by the Tuatha De. For centuries, they ruled the place until the Milesians came and drove them west. While diminished, the three tribes of the Fir Bolg can still be found on the Aran Islands. With the sole exception of the Fir Domhnann tribe, the Fir Bolg are Christian, converted by Saint Patric. The Fir Domhnann have sympathy for their bastard Fomoir blood and worship the goddess Domnu instead. While the Fir Bolg have little power as rulers, they are valued as counselors for their wisdom. However, the Fir Domhnann resent the rule of man, for it was their ancestor, Gannan, who was given Connacht to rule after the Fir Bolg came to Ireland.

The nobles of Connacht also protect and consult with several druids. Few in Connacht would dar bar the way of a druid. Those hedge wizards with a gift for divination are now seeing omens of change, and advise the people to prepare. Within a generation, the English may cross the border. Magic and Faerie auras are plentiful in Connacht, and even within the Dominion, hedge wizards seem to thrive. Vis is abundant, though rarely in great quantities. The Coill Tri is an imposition on the local druids by the Ordo Hiberniae, and many resent the restrictions endured and the tribute paid every seven years. They must give up seven Gifted Connachta children to the magi each Tribunal, and that does not sit well with them. Still, just as the Fir Bolg and Tuatha De owed tribute to the Fomoir and the kings of Connacht owe tribute to the English, the druids must accept that they owe tribute to the magi.