Spears of the Dawn by Libertad!

System Overview

Original SA post

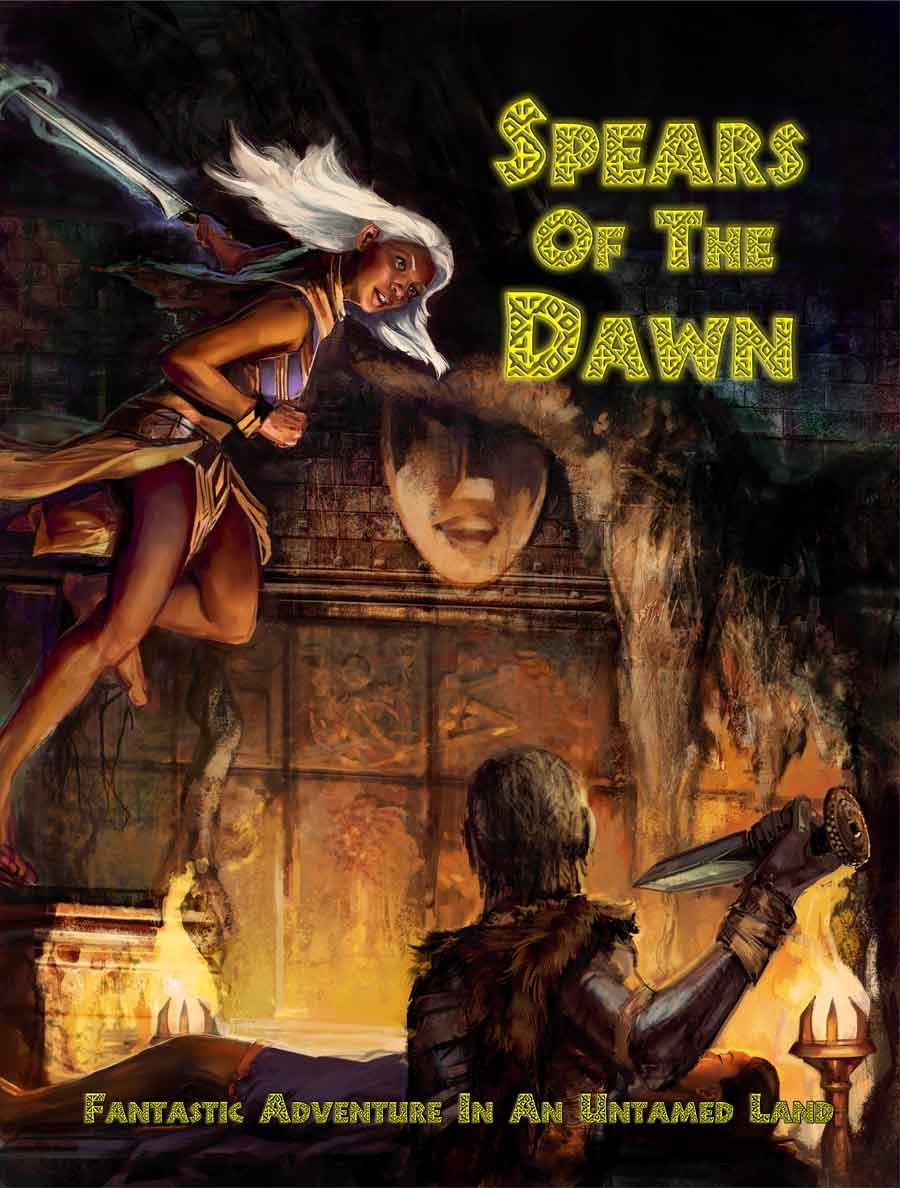

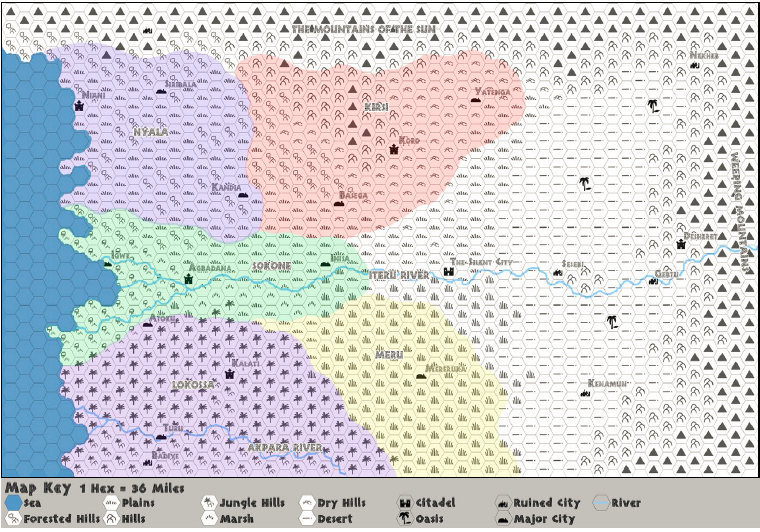

Once upon a time, there was a guy named Kevin Crawford. He designed role-playing games of the old-school variety, namely Dungeons & Dragons retroclones and supplements. He was hanging out on an RPG message board when the topic of racial diversity in games came up, and he heard the familiar mantra "That doesn't sell!" repeated. "Gamers aren't interested in fantasy Africa, they just want European and Asian (namely Japanese) stuff!" This irked Crawford, a lot, and so he decided to hedge a $3,000 bet. He bet that not only could he design a cool Fantasy Counterpart Africa RPG drawing inspiration from authentic myths, folklore, and history, but that it would be popular. To that end he buried himself in several months worth of game design and research on the continent in medieval times, hired a bunch of talented artists (whose work he released into the public domain with their consent to provide inspiration to others), organized a Kickstarter for funding, all to make a superb RPG.

And he succeeded. Not only did Spears of the Dawn get a lot of rave reviews and managed to avoid the more racist and stereotypical "unga bunga land" portrayals earlier work engaged in, it became one of the hottest-selling D&D retroclones on Drive-Thru RPG last year. The whole "fantastic adventure in an untamed land" phrase is sort of unfortunate to me, as it conjures up specific imagery which is largely inaccurate of the setting inside. There are definitely lots of ruins to explore and tiny isolated villages, but there are also great nations inspired by the real-world empires of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai which built grand palaces and possess the knowledge of metallurgy, an order of Paladin-esque Sunriders who defend the common folk from evil humans and monsters, and mighty sorcerers and clerics who have the king's ear and can decide the fate of entire communities. The setting's about as "advanced" as most D&D settings are.

System Overview

Spears of the Dawn derives its ruleset from Stars Without Number, another retroclone designed by Kevin Crawford, which in turn derives inspiration from the Frank Mentzer-written version of Basic Dungeons & Dragons. It adopts plenty of classic tropes, from the 6 ability scores to saving throws, although its classes, magic, weapons, monsters, and more take on the trappings of African folklore and legends. There are many varieties of sapient supernatural species, although only humans are a playable option (who in turn gain different starting skills based on their background).

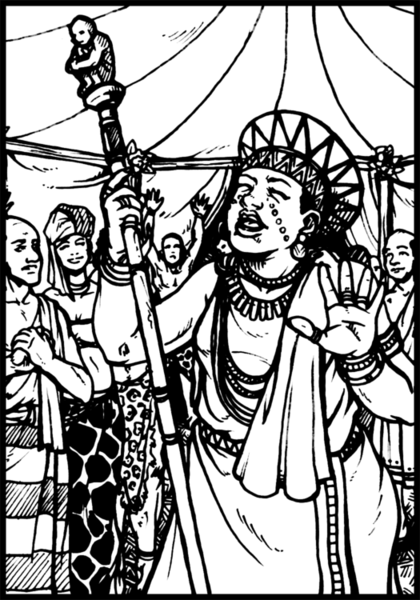

As for the classes, there is the Griot (pronounced "GREE-oh"), bards and historians whose songs and orations are so good they might as well be magic; the Marabout (pronounced "MAHR-ah-boo"), priests who have a special connection with spirits and gods and can work their magic in this world by gaining their favor; the Nganga (pronounced "GAHN-gah"), people born with the ability to manipulate ashe, the fundamental potency of existence, which gives heat to fire, hardness to stone, and cunningness to the wise among other things; and the Warrior, those who do not rely upon magic or the griot's songs to perform feats of heroism. In addition to being the hardiest and most-skilled of the classes, warriors gain access to idahuns, or "replies," special abilities which the warrior has mastered to use against foes. Yes, fighters have class features nobody else gets or can easily replicate in Spears of the Dawn (and I'm not talking about piddly stuff like Weapon Specialization)!

The game also incorporates a skill system, unlike much of its fellow old-school brethren. It lies somewhere in between the complexity of 3rd Edition's fiddlyness and the "say what you want to do, DM sets the DC" minimalism of most OSR games.

Setting Introduction

In times long past the kingdom of Deshur warred against the Nyalan Empire. Out of sheer desperation, the Deshurite King turned to evil magic to turn the tide of war, and in turn doomed his own people to unending unlife. The Eternal, as they became known, were little more than undead monsters who cut an orgy of destruction across the Three Lands. Were it not for an alliance of the five major nations, they might have even been victorious, but mighty heroes with the help of the nation's armies organized resistance against them.

It has been forty years since the Eternal were driven back into the inhospitable black sands of the east, but remnants of their soldiers and sorcerers still lie in fortified underground strongholds and tombs, biding their time and striking out against those too foolish or unknowing that tread too closely. The past is forgotten as the five kingdoms remember old disputes and sever alliances, as border quarrels deniable incidents sprout up along their borders. Whether it's tyrannical nobles, bandits and monsters lurking in the wilderness, the troubles of the Three Lands seem beyond the reach of even its kings and queens.

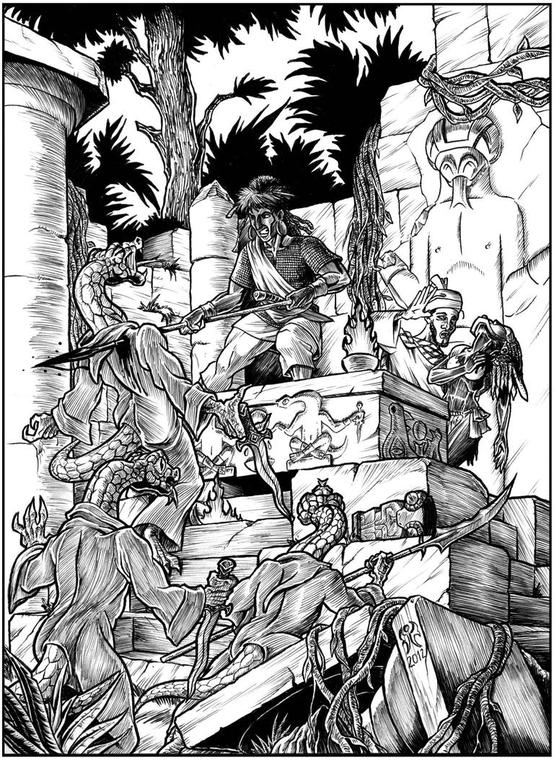

It is a time of trouble, but there is still hope. In addition to wandering adventurers who slay monsters plaguing villages, spiritual leaders who call upon spirits to aid the sick, and sorcerers who break the curses of their evil brethren, there are the Spears of the Dawn. An organization formed by the last Nyalan emperor to fight the Eternal, these men and women come from all nations and walks of life to travel wherever they're most needed and wipe out the undead remnants. Today they are on hard times, no longer officially supported by any kingdom and often little more than wandering adventures. It is expected that the Player Characters number among the members of this heroic order.

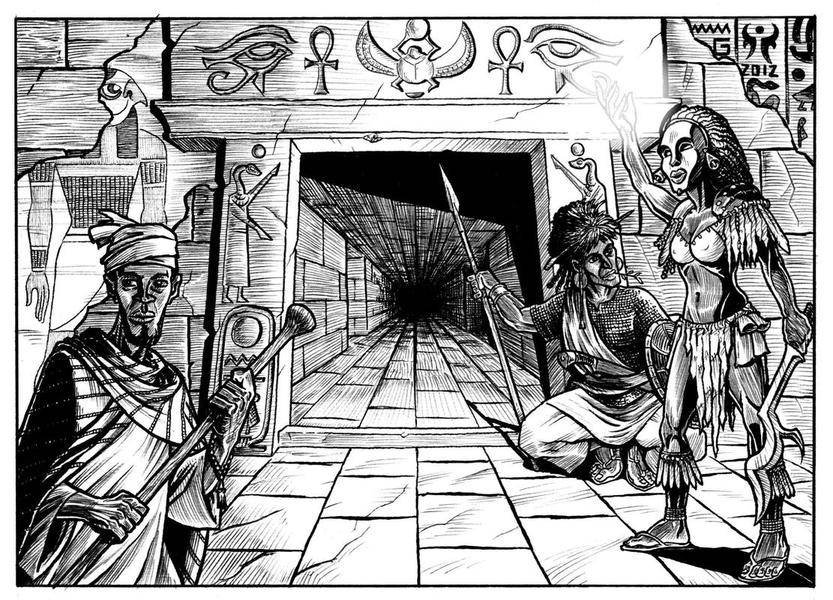

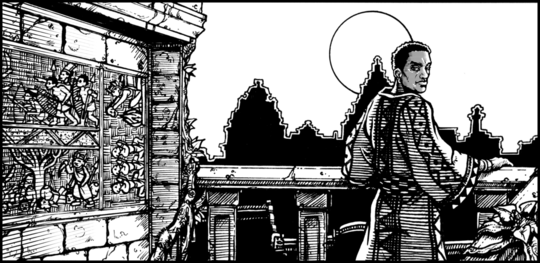

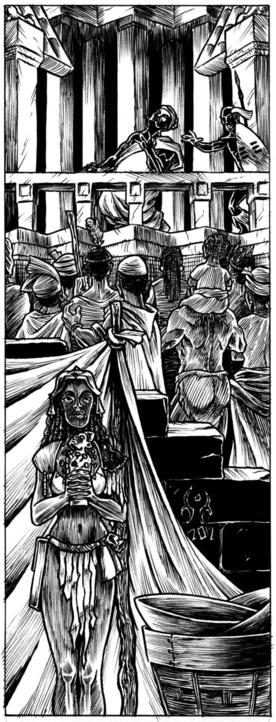

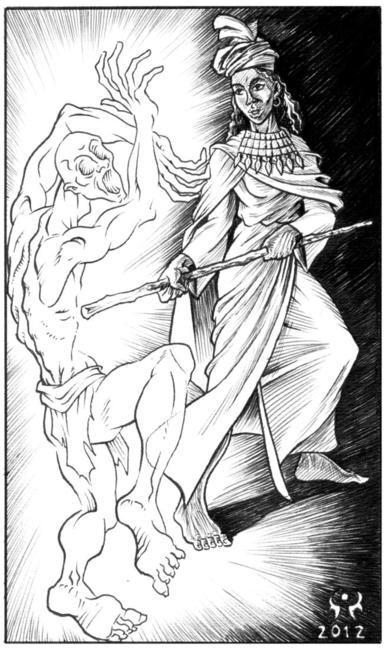

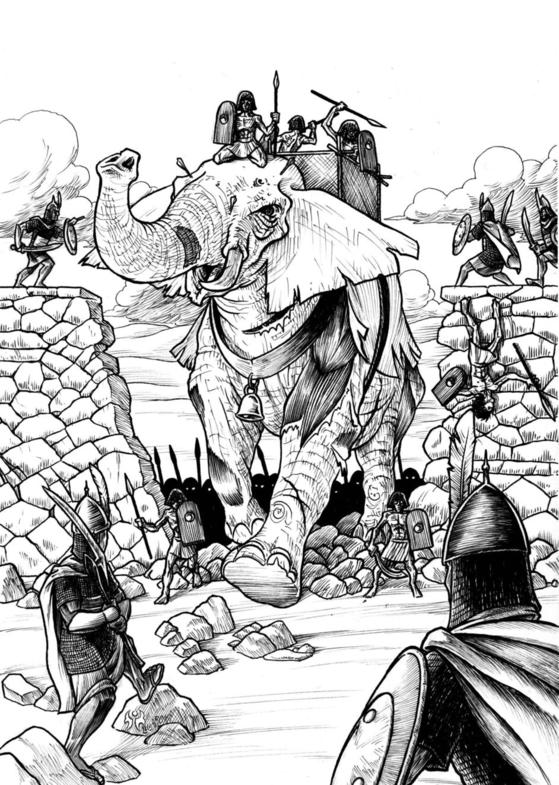

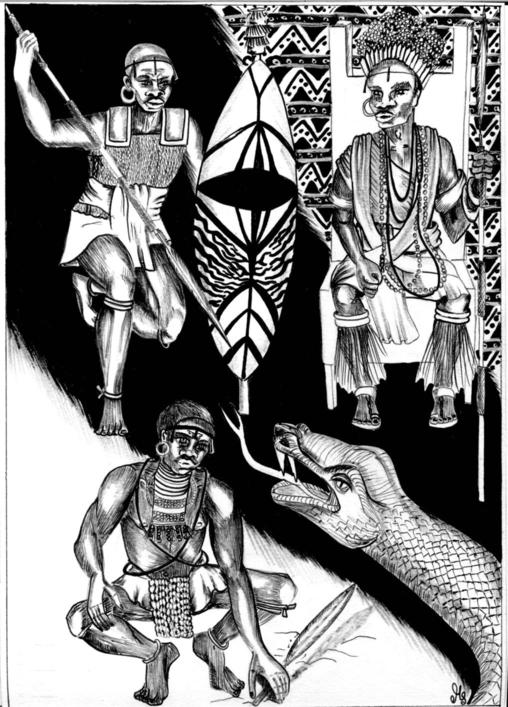

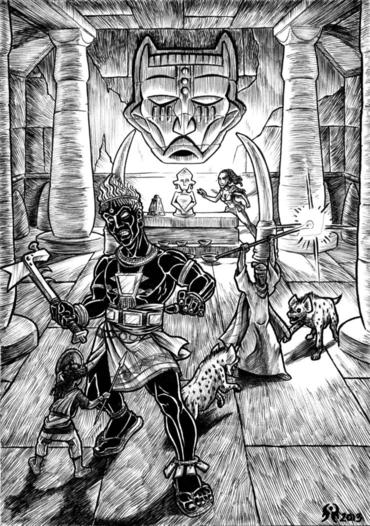

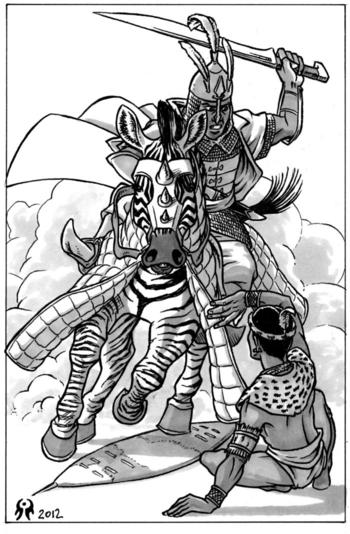

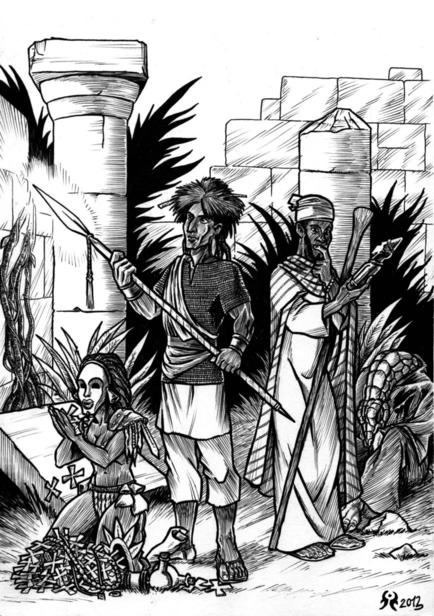

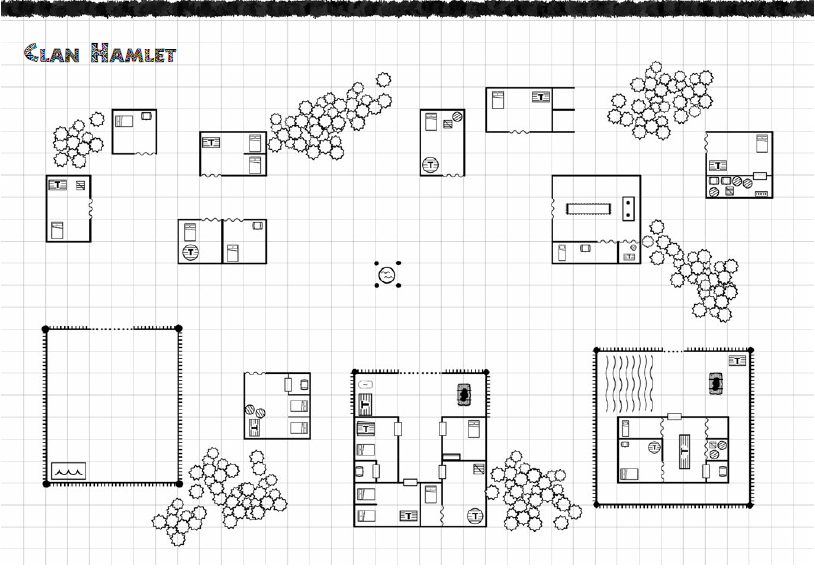

Adventurers getting ready to explore an Eternal tomb.

It might be odd to end my first post on the introduction, but the first chapter of character creation covers a lot of ground which I believe is served better in its own section. Hopefully I've whet your appetite regarding this RPG to look forward to more updates!

Next time, Chapter One, Part One: Ability Scores, Homeland and Backgrounds, and Classes!

Creating a Character

Original SA post

Chapter One: Creating a Character

The chapter starts off with some pretty basic information you see in plenty of RPG corebooks. "Try to design characters so that they work well together and have a common goal," "choose a motivation," "explain how/why your PC came to be a Spear (of the Dawn)," but it also says that the game is intended to be a sandbox game. Basically, one where the players decide on what to do and where to go in the world, and the DM reacts to this, and that there's no narrative plot armor built into the rules to save you from poor choices. The specifics of sandbox gaming are dealt with in a later chapter, and you can find many discussions of this playstyle on old school D&D blogs and message boards.

Attributes

First off, we have the classic 6 ability scores, which are known as attributes in this game: Strength, Intelligence, Wisdom, Dexterity, Constitution, and Charisma. Rolling 3d6 six times is the classic way of generating them, although one can remove points from attributes above 13 to add to ones below 8, but not to the point where the former dips below 13 or the latter increases beyond 8. The reason for this is that 8-13 is the baseline average, with a 0 modifier. A range of 4-7 grants a -1 modifier, 3 a -2, 14-17 a +1, and the vaunted 18 a +2. This way you can shore up pathetic ability scores from high attributes you don't really need. Each class also has 2 Prime Attributes, which are vitally important to that class and thus allow you to bump up an attribute to 14 in one of them if it's lower.

If you want, you can dispense with rolling and put a value of 7, 11, or 14 in your attributes, provided you don't have more 14s than 7s. You don't get your "free 14" prime attribute if you go this route, though.

Origin

Not that you've got your attributes and character concept, you move on to the next step, your Origin. This is a combination of your character's homeland (usually one of the five Kingdoms), and their background (the occupation/way of life he grew up with in said country). Your background does not restrict what class you can choose, but it instead provides 6 skills which your character starts with in basic competency (Level 0). If your chosen class gains one or more of these skills as bonus skills, then you move up to the next level of competency (Level 1), which indicates a long professional expertise. Therefore, it can be advantageous to choose a background which fits with your class. If your DM's okay with it and it sounds plausible enough, you can design your own custom background by picking 6 skills.

The Kirsi ("KEER-see"), formerly an eastern province of the Nyalan Empire, are a hilly nation of warriors famed for their armored lancers and iron-clad cavalry who cut through Eternal legions in the days of the Long War. Even the most impoverished peasant among them is taught in at least one kind of weapon, and their rulers wouldn't dare think of disarming the populace. For the last 40 years the nation's feuding noble houses engaged in successions of land takeovers and skirmishes, displacing many Kirsi and sending once-mighty family dynasties into exile. Even the kingdom's ruler, the Dia, can only enforce the territory his men walk over. Their cities are made of adobe and scrub-oak, their palaces and manors of quarried stone.

Many of their backgrounds tend towards some martial inclination (bandit, noble, scout, soldier), although the most interesting one's the Sunrider: your PC grew up training under paladins of the Sun Faith, who fight for justice and defend the common folk from noble depredations.

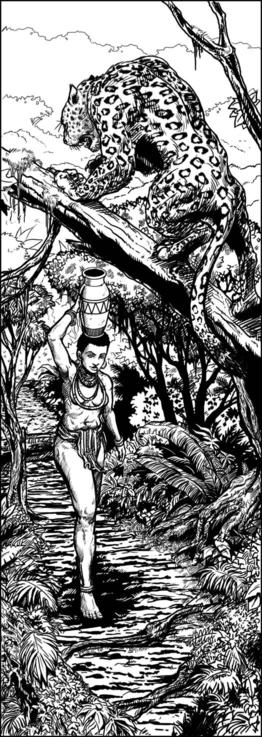

The people of Lokossa ("low-KOH-sah") live in a the southern rainforest kingdom of the Green Land, standing stalwart against the monstrous Night Men who lurk across the Akpara River. Their society is a tyrannical magocracy, where the nobles are mighty Ngangas ruled by the Ahonsu (sorcerer-king). Their magical protections and rituals kept their nation autonomous and repelled foreign threats for centuries, although the mages rule the commoners with an iron fist and work them to the bone. Whenever the Night Men grow strong, the noble clans selected human sacrifices among the commoners and slaves to fuel their magical power, which is grimly accepted as a necessary evil (hundreds will die so that thousands may live"). The people wear little in the humid jungle aside form chiffon-light wraps of woven leaf fibers dyed in bright, beautiful colors.

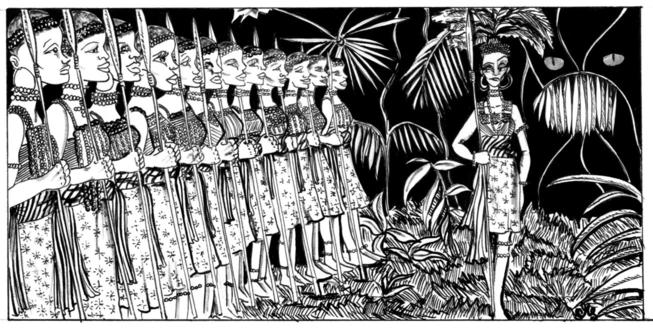

Backgrounds tend to vary, from the lowly peasant and city-dwellers and runaway slaves, to commoners with magical talent plucked from their families to serve a noble house. The Lokossan Reapers are an all-female military unit of warriors who fight with signature two-handed "great razors," and have an honored place in Lokossan society.

The Meru ("MAY-roo") are a nomadic people wander the golden savannahs and grasslands of the southern Yellow Land, dwelling in semi-permanent homes of thatches and thornbushes and taking their cattle to wherever the land is most plentiful. They are descended from the Sun Faith worshipers of the ruined kingdom of Deshur, when the rulers turned to the loathsome Gods Below for aid. The Sun Faith worshipers fled to the savannahs and learned how to survive from the indigenous groups living there. After generations of intermarriage they became the Meru people of today.

In the intervening years Eternal forces journeyed into the land to slaughter them, forcing them to ever be on the move. Eventually they turned the tide, fashioning war staves and throwing clubs to crush Eternal bones as their Marabouts seared their flesh with the power of the Sun. They are proud of the role they played in the Long War, and how their traveling life helped keep them one step ahead of their undead enemies. The Nyalan Empire in the days of old tried to claim the lands inhabited by the Meru, but were unable to effectively rule or tax them due to their legion's inability to even find the nomads in the great grass sea.

Meru are a religiously devout hunter-gatherer society, and their backgrounds reflect this (herder, scout, trader, etc). They don't have warriors or standing armies because everyone's expected to be able to defend their herds (although Meru Sunstaves are a background of gifted individuals who wield large staves as signature weapons). Olabans are loremasters who pass down the lore of their Sixth King ancestors to help counter supernatural threats, while their priests are Sun Teachers who have no temples or shrines but great knowledge in the holy scripture.

A once-proud civilization which ruled over much of the Three Lands, the Nyala Empire ("nn-YAH-lah") is but an empire in name only today. It is a northwestern land of rolling hills, meadows rich with water and rain, and beautiful broad-leafed forests. Their human ancestors learned many secrets from the giants of the Mountains of the Sun, which they used to work metal and erect grand buildings. As Nyala's land grew, so did its ambition, and it was this drive to conquer which drove the Deshirites into the eastern sands. When the Eternal marshaled their forces, the Nyalans were unprepared and spent most time holding onto existing provinces than to drive them back, which resulted in the loss of many regions and cities as well as the declarations of independence of Kirsi and Sokone. It wasn't until the days of the last Emperor Kaday that the country formed an alliance with its neighbors, formed the Spears of the Dawn, and drove back the Eternal. He died in battle, and now the Nyalans look to their recent past, reminded of all that they had lost.

Nyalans have a tendency to be proud and haughty; peasants and nobles alike have a near-encyclopedic knowledge of centuries-long family trees, and can make tenuous claims to great heroes and historical landmarks. Their nation might be in decline, with peasants burdened by heavier and heavier taxes, and dynasties see their fortunes decline and inability to protect their own land, and yet some of the most zealous venture beyond to find something, anything to make their country great again.

The backgrounds reflect this, ranging from Nyalan nobles or "hollow princes" who could no longer hold onto his land and legacy, artisans who blend elegance into even the coarsest of work, courtiers and hangers-on to the upper class and scheming plotters, historians forced onto a life on the road after being let go by a noble house, and even the mere peasant and soldier.

Our fifth and final nation, Sokone ("so-KOH-nay") is located in the relative center of the Three Lands, the mighty Iteru River cutting through the breadth of its fertile land. Sokone is the richest of the nations, home to cosmopolitan trade hubs importing and exporting all manner of goods, from rare rainforest herbs to fine Kirsi steeds. Almost anything can be for sale, provided one knows where to look and has the right connections.

Sokone was one of the first provinces to break away from Nyala in the time of the Long War. Although the Eternal armies were repelled by large bodies of water, the war was still devastating to the country. Their capital city of Chakiri was overrun and still serves as a stronghold for the undead to this day (now known as the Silent City). Farmlands and houses along the coastlines were burned so that even those who fled onto the safety of the river barges had nothing left to return to at their homes. Were it not for their geographical position among trade networks, and the merchant family’s wealth, it would’ve taken Sokone far longer to recover.

Sokone is the most racially and religiously diverse of the five kingdoms. From the jewel-colored eyes of Nyalan nobles to the stern features of the Kirsi, the traits of the major ethnicities can be found in all combinations among Sokone. Temples of the Sun Faith and shrines to all manner of spirits are common features along active city streets. Clans and families have little reluctance towards marrying foreigners, and alliances form more around trade and business opportunities than matters of nobility or lineage. On the other hand, the people of Sokone are very individualistic, and families are expected to stand on their own two feet with minimal outside help.

Sokone backgrounds tend towards mercantile varieties, such as the arbiter who is trained to settle disputes (both legal and otherwise), artisans, traders, and entertainers earning a living, riders employed by rich merchants to monitor the affairs of distant lands and return to them with news, peasants and riverfolk who perform labor in the rice fields and live day and night on traveling barges, and syncretic priests who call upon all manner of known and unknown higher powers.

In short, the backgrounds serve their purpose, and none of them are what I'd call unbalanced. Granted, a few are more interesting than the others, but you should be able to design the character you want unless you're dead-set on some really weird backstory.

Choosing a Class

Player Characters in Spears of the Dawn are a cut above the cloth. While anybody can learn how to swing a sword, placate the spirits, or sing well, the powers and abilities of character classes are special in both their training and sheer potential for greatness, even at their lesser levels.

There are four classes to choose from: Griot, Marabout, Nganga, and Warrior. Once selected, you are locked into that role, and cannot trade in levels or multi-class as you might be able to in other RPGs. There is some variation in specific abilities, but overall each class tends to be good or specialized in some general area.

Each class has universal core traits: hit dice used to roll hit points, saving throws to resist negative effects, an attack bonus to determine their overall fighting capacity, prime attributes, and a list of class skills. Additionally, each class gains a list of bonus skills to receive basic competency in (or grow to Level 1 if they overlap with existing background skills), plus one in a class skill of the player's choice and one bonus skill which could be anything they want. Classes advance at the same rate of experience, and the maximum level in the game is 10.

I will be detailing the magic spells and effects, including Griot songs, in their own Chapter: Magic.

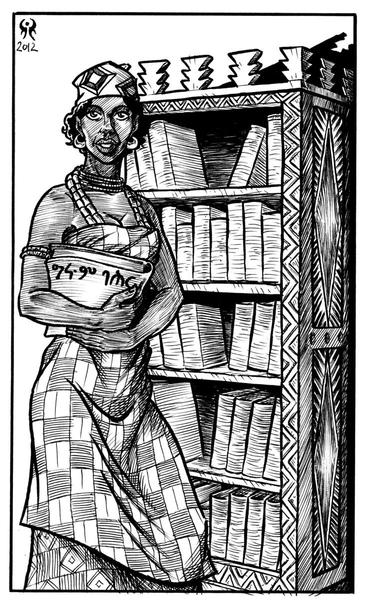

The Griot maintains the history and traditions of a culture's people. They are responsible for judging the worthy and the wicked, share their memories and lore with others, and channel the truthfulness of things through their praise-songs and verbal castigations. In short, they are the "bard class." They're rather squishy (1d6 hit dice), have an average attack bonus, and their saves are geared more towards evasion and avoiding mental effects, but they have a versatile list of class skills to reflect their role as scholarly entertainers.

Their major class features are their Songs, near-magical effects which increase in power as the griot gains levels. Whether it takes the form of a song, oration, chant, or other verbal sound, listeners realize that the griot is no ordinary entertainer and that these words carry a substantial, visible weight. Basically, a griot begins play knowing two songs and can learn an additional one every time they gain a level (or learning it from a fellow griot or tome they penned), and use a point-based system where songs cost a number of Inspiration to use. Using a song takes great effort, and too many in quick succession can tax the griot as they become unable to use the right words and melodies in the right order and fashion. At 1st level they can learn only minor songs, but at 4th and 7th they can learn Great and Ancient Songs. Their 10th level capstone ability allows them to pick 2 minor songs and use them at no Inspiration cost. Songs generally involve placing targets in a certain estate, bolstering the abilities of allies, or relying upon epics and lore to discover and remember old knowledge.

Overall, a class which is good at what it does and fits in well with the setting.

Every village has its people versed in their culture's religion and the service of the spirits. Religious festivals and celebrations are communal activities, as the favor of those worshiped is seen as the duty of everyone and not a specialized order of clergy. Even then, there are times when the specialized skills of one close to the spirits is needed, and the Marabout serves that role.

Marabout are not just priests and priestesses. They are people who fashioned close relations with a spirit or spirits, and in exchange they gain magical powers in line with the spirits portfolio. Some have to spend years earning their good will, while some are born able to use miracles by instinct, having been watched by an otherworldly patron since they were in the womb. Most marabout in the Three Lands follow either the Spirit Way (catch-all term for people who honor all variety of spirits) or the Sun Faith (monolatrist faith which views the Sun as the greatest spirit of all and pay homage to him and him alone).

Marabouts have a 1d6 hit dice and average attack bonus, and their saves are more geared towards resisting magic and saving them in times of pure luck. Their skill list is fewer than the griot's, generally a few social skills and knowledges. Their primary class feature is their access to Spheres, which are much like Cleric domains from Dungeons & Dragons geared towards a certain theme, and and one of them chosen by the PC grants an always-active Gift or benefit for the Marabout. A marabout PC chooses two spheres at 1st level, representing their friendship with spirits in that portfolio. Alliances can change and evolve, however, and the marabout can gain an additional sphere at 3rd, 6th, and 9th level, and can trade out any number of spheres whenever they gain a level. Marabouts of the Sun Faith, however, must always keep the Sun sphere as one of their active spheres. In exchange, they can cast one more spell per day per spell level.

Marabouts use the all too familiar Vancian spell system, where they spend slots of certain spell levels to cast their spells. Whereas standard D&D clerics and wizards can choose their spells ahead of time, marabouts can only cast spells from their spheres. At 10th level they may choose a 1st level spell of a sphere without a permanent effect to be able to cast at will. This makes the class rather specialized at low levels, although they become more versatile in ability as they gain levels.

The eight available spheres are Curing (healing magic and immunity to disease Gift), Death (weakening enemies, speaking with the dead and raising the dead, can halt bleeding others as a Gift), Herding (good with animals and +1 to your Constitution modifier Gift), Passion (manipulate emotions, +1 to Charisma modifier Gift), Spirits (banish and summon spirits, can speak with spirits and see them as your Gift), Sun (light and fire magic, see in perfect darkness and radiate light at will as Gift, available to both Spirit Way and Sun Faith), War (buff spells for combat, +1 to hit rolls with specific weapon group as Gift), and Water (water and weather magic, can breath and swim in water like a fish as Gift).

The Marabout's role in the party highly depends upon the spheres you select. They can be classic battle-priests of D&D with Curing and War, they can be pseudo-druids with Herding and Water, and classic undead-slayers with Spirit and Sun. The choices are up to you!

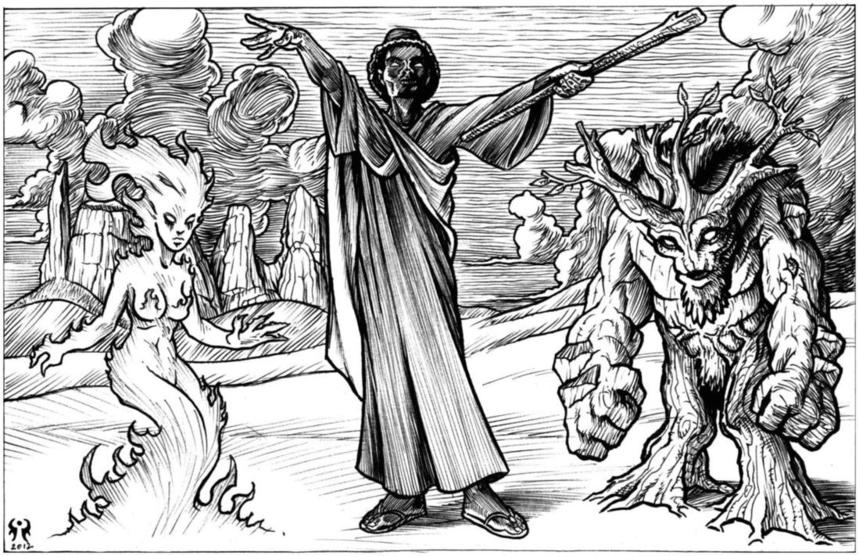

The Nganga are those few people gifted (or cursed, depending on how you look at it) at manipulating the universal force known as ashe. This art is inborn and cannot be taught, although most of these folk are destined to live unaware of it, their unconscious desires wreaking magic around them. However, with proper training and knowledge of the required rituals and material components, a nganga can achieve feats both wondrous and terrible. From laying curses upon foes to taking the forms of beasts, the magic wielded by a nganga makes them feared and respected across the Three Lands. As long as they restrict their magic to cursing enemies and warding their own communities against evil magic, these sorcerers are tolerated as a necessary evil (or are part of the ruling class in the case of Lokossa).

The Nganga is very frail, with a d4 hit dice and the only one which does not have Combat skills as class skills, and a poor base attack bonus. Their saves are geared against resisting magic and mental effects, and are bad at resisting physical effects and evading danger.

While a Griot's songs are not technically magical, and the Marabout relies upon spirits from another world, the Nganga's magic is entirely internal and of this world. They need to channel their powers into proper receptacles, forcing them to carry specific charms, masks, pieces of clothing, and similar restrictions to cast their spells. Unlike marabouts, they cannot cast spells while wearing armor. Nganga Sorcery is divided into two kinds: ritual spells, which has no limit to the number of times they can be cast but often have long casting times (30 minutes is the fastest one of all) and sometimes expensive material costs. And nkisi spells, which use the per-day Vancian system and must be imbued into nkisi, or small handheld objects. Both have spell levels, and thus can only be learned by a nganga who meets the proper character level to cast them. They can learn new spells by gaining levels or from a fellow tutor (none of which freely part with their knowledge, and prefer favors and quests to vulgar trade goods). A nganga always has the option of preparing more slots than their level allows via additional nkisi, but failing an Occult skill check causes all of the spells to go off at once with the nganga as the target.

Nganga are a potentially powerful class. They are more versatile than the marabout, and many of them tend to be direct damage, debilitating curses, or defensive wards or rituals to build minor magic items. They do suffer the common problem of low-level old school wizards, where they can fire off only a single spell at 1st level and become squishy targets with almost no offensive capabilities.

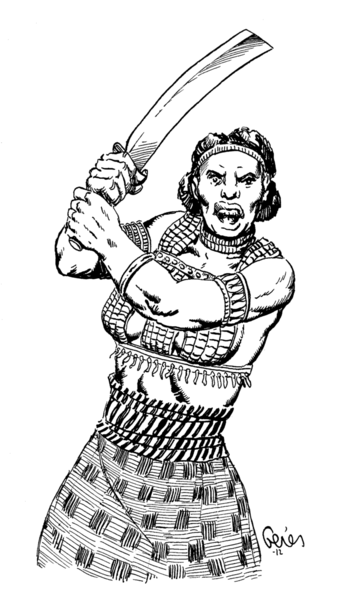

The Warrior has a rather misleading name. Although they are mechanically combat-based, the available options allow you to make a skilled thief character. Warriors are pretty much anyone who relies upon their own skill and wits without the aid of magic or songs. Fighters not only have the best hit dice (d8) and attack bonus, their saves are good all across the board, and they gain athletics and all combat skills as bonus skills. And their class skills are not too shabby either, including the aforementioned groups as well as more thiefy stuff.

Warriors gain access to idahuns, or "replies," techniques they mastered through training. Almost all of them are always-active, only a few are limited use. The warrior gains an idahun of their choice at 1st level and gains an additional one at 3rd level and every odd-numbered level thereafter. There are 12 total, enough for me to cover them all. They tend to vary in effectiveness, with some useful for any character and a few dedicated more towards specific builds. What I like is that some of them are open-ended as to whether they might be supernatural, or just superior training or luck. For example, the "Two Lives" idahun might be the warrior simply possessing extraordinary luck, or the spirits are watching over him.

The four great ones, which any build can improve upon, are:

Blessed and Graced is great because your PC gains an effective 7 points of armor bonus (equivalent to heavy armor), as they learned to fight unarmored. They can still use a shield, and there's no downside to this as it's superior all available armor options with none of the drawbacks. You won't be able to use this while wearing magical armor, but you won't find that stuff often until higher levels.

Charmed Steel, where your attacks wound all foes normally, even if they'd otherwise be immune to or suffer reduced damage based on weapon type. Additionally, all weapons and armor you wield are treated as magical, and gain a +1 bonus at 4th level and increase by 1 every 3 levels.

Two Lives, where you simply fall unconscious for 5 minutes if you'd otherwise die or bleed out from your wounds. You can die normally if struck while in this state, and must spend a week in celebration to honor the spirits who saved you or being joyful over your good luck before you can use it again.

Washer of Spears, which grants +2 initiative and you can never be caught surprised.

And for the rest:

Born with a Blade is lackluster, granting you a +1 to hit and +2 damage with a weapon group of your choice.

Deep-Rooted Soul grants you a +2 on magic saves (putting you equivalent with the Nganga, the best magic save in the game), and you can't suffer negative levels from energy drain. Useful for most builds, especially magic-using enemies and undead.

Honed Skill and Sagacious Warrior are meant for the skill-user builds. The former lets you pick one skill you're really good at, and you treat a roll as a 12 on the die (2d6 skill system) once per day. Sagacious Warrior grants you basic proficiency in 3 skills of your choice or raises existing ones to Level 1, or any combination thereof. This last idahun, along with all others, can only be taken once.

Dreadful Shadow and Honored Steps are reputation-based, and only one of which can be taken. The former grants you bonuses on intimidation-based rolls, and you're immune to all fear effects. Honored Steps increases your Charisma modifier by 1 and automatically assumed fit for leadership positions. Both are rather situational.

Tireless increases your Constitution modifier by one (augmenting your hit points), and you can perform physical exertions all day long, and you sleep light for the first four hours. An all-around good idahun.

And finally, Roof of Spears. Once per combat, you can instantly move to interpose yourself with an ally within 30 feet, taking the damage or effect meant for them, even after dice are rolled. You can only defend against physical attacks. Good to have if one of your PCs is wounded or a squishy nganga.

Overall, I really like the Warrior class. It is very versatile both in and out of combat, and I like the touch of unique class features with good effects. It makes the warrior feel unique belong "have the best hit points and saves and all the proficiencies" of other old-school fighter classes.

Skills

The other major aspect of character creation, Spears of the Dawn uses a skill system. Skills range in 6 variables: lack of a skill, where you don't have even basic training and suffer a -2 penalty (and can't even roll for harder DCs at all); Level 0, basic proficiency; Level 1, years of training; and all the way up to Level 4, which indicates legendary ability.

When performing an activity with a reasonable chance or consequences of failure, a character rolls 2d6 and adds their skill level and the attribute modifier most relevant to the situation, with DCs ranging from 6 (simple tasks for trained people) to 15 (barely possible in a theoretical sense). There are 20 skills, a few of which have specializations. It costs points to upgrade skills, and characters have only a set amount per level to spend. The cost increases exponentially between skill levels, and more so if it's not a class skill, so even griots and warriors aren't going to be getting good at all of them anytime soon.

Some skills are specialized and require specific knowledge, such as Artistry (art and entertainment stuff), Culture (your own or others), and Trade (common medieval occupation), but most are broad and all-encompassing. Some skills especially useful to typical Spears or adventurers, such as Athletics (helps you wear heavy armor in hot climates in addition to movement stuff), Occult (supernatural stuff), Perception, Navigation (where am I?), and Survival (living off the land). You even have Persuade, a social skill to change people's disposition towards you, while Leadership and Tactics can help keep obedience of subjects and manage affairs in risky situations.

What's interesting is that Combat is a specialized skill. Instead of using the 2d6 system, you buy up skill levels in a certain type of weapon (axes, blades, clubs, spears, or missile weapons), and you add the skill level to your attack bonus along with the relevant ability modifier. This is in lieu of a proficiency system, and I sort of have mixed feelings on it. On the one hand, it complicates things when transferring from other games ("can I use this weapon or not?"), but it allows for some customization in what you're good at unlike some more restrictive retroclones.

Final Touches

The last bits of character creation include choosing of starting languages, rolling for starting wealth (with silver trade ingots the universal basis of currency) along with a table to gear to buy, and roll for starting hit points.

Unlike other retroclones, you roll your entire hit die value every time you level up. And if the total is equal to or greater than your current hit points, then you gain that new value instead. This results in the potential for sudden large increases, and can mitigate the effects of a bad roll the previous level. Rolled a 3 for your 1st level Warrior? Not to fear, upon hitting 2nd level you always have the potential to get as high as 16! Only problem is, there's the slight chance that you might not get any hit points at all upon leveling up.

Thoughts so far: I like what Crawford did with the classes. They're quite versatile for an old school retroclone, and the fluff text fits really well with the setting while letting you know this is not your standard Fantasy Europe. 3rd Edition fans like me might appreciate the skill system to better create your character, and the background system helps ground your character in the world.

Next time, Chapter Two: Systems and Rules!

Systems and Rules

Original SA post

Chapter Two: Systems and Rules

This chapter is a collection of all those common rules you see in RPG rulebooks covering plausible situations adventures might come across in play. Carrying capacity, overland travel, natural healing, that kind of stuff. It's an oddity that these rules are near the front of the book, but that actually makes sense. In other retroclones and D&D Editions, such a chapter's usually farther into the book, after magic and equipment and other stuff like that. But this is actually a good idea, as these rules apply to everyone, and they're only 10 pages long (in keeping with the rules-lite ascetic of many old school games).

Our first section are skill checks, covering the skill system of Spears of the Dawn. In short, you roll 2d6 and add your Skill level, the relevant ability modifier, and other miscellaneous modifiers as determined by the DM. There's no check for things where you can accomplish the task eventually where time is not an issue or something you do regularly for your background. Otherwise, the target number (or difficulty) are in intervals ranging from 6 (simple tasks for trained people) to 15 (almost impossible). Very open-ended.

Opposed rolls (like sneaking up on a sleeping monster) are done by the participants rolling opposed skill checks, with the higher result winning (ties are rerolled if they don't make sense in context).

Extended skill checks are rather simple, where the result of a success or failure determines if you finish in time when it's convenient, or is rolled once for each interval of time.

Also, good advice to discourage those asshole DMs who make players roll for everything:

quote:

As a good rule of thumb to determine whether or not a PC should get a concept success, think about whether failure would make the PC look incompetent at their role. If not-infrequent failure at a type of skill check would have gotten them drummed out of their profession, then they can be assumed to automatically succeed at similar tasks.

Don’t feel obliged to let a character’s concept creep too far. One who bills himself as a “jack of all trades” might well have a wide range of skills, but letting him get a concept success more than once a session is probably more than he needs. The goal is to let PCs be good at what they are about, not to let someone bypass half their challenges with a well-worded character concept.

We then get brief overviews of the five saving throws. Physical Effect involves stuff like resisting diseases, poisons, exhaustion, and other tests of health and endurance, Mental Effect covers griot songs and supernatural effects that directly affect your mind, Evasion covers situations where you must dodge out of the way of something, Magic covers any magical effect which does not follow under any of the following categories, and Luck for when your wellbeing hinges upon dumb luck and not skill.

Also, suffocation and falling damage. Long story short, you die if you go for 5 minutes without air (and bad stuff happens in the intervening minutes), and suffer 1d6 damage per 10 feet fallen (to a maximum of 20d6) with a luck save halving the damage.

Overland travel is rather straightforward, where the average human adult travels 3 miles an hour and can be modified by encumbrance, terrain, and any mounts they have.

Combat is where we really get to the details! Surprisingly this section's only 2 pages long. Mainly it covers initiative (roll 1d8 and add dexterity modifier to see combat order), actions and movement (free actions which require nothing and normal actions which can be done in one round), spell disruption (ngangas and marabouts lose whatever spell they were in the process of casting if hit with an attack), movement (60 feet per round and one action, or 120 feet doing nothing but moving), and attack rolls.

Attack rolls are different in this game, in that the target number is always 20. An attacker rolls a d20 and adds their base attack bonus, their weapons skill level if applicable, relevant ability and miscellaneous modifiers, and the opponent's armor class (a lower value is better, naturally). There are no critical hits in this game.

Other than this, that's it for combat! Quite simple, really!

Encumbrance and armor determine carrying capacity. A character can ready a number of items equal to half their Strength score, ones a person can easily ready on their person and can be drawn as part of an action in a round. Armor counts as a readied action. You can have a number of stowed items equal to their Strength score. You can ready or store 2 or 4 additional items in exchange for becoming lightly or heavily encumbered, respectively.

Rather than listing out weight for all equipment, Spears of the Dawn list an Encumbrance number, determining general weight and unwieldiness. Most items are encumbrance one, and most small objects have no encumbrance. Items with an encumbrance score higher than 1 are tougher to carry, and thus count as additional ready or stored items.

Also, the hot climate of the Three Lands makes wearing heavy armor impractical in most situations, and thus are not in high supply or demand. You suffer hit point damage equal to twice its encumbrance if you wear it long-term. As such, most warriors don heavy armor immediately before battle or when they're going to fight mounted (riding reduces the penalty) or in the shade. Having ranks in the Athletics skill reduces the penalty.

Injury and healing are semi-detailed, where people reduced to 0 hit points are at risk of dying if not attended to with a successful Medicine roll of 8 or a healing spell, and must make Physical Effect rolls if left without treatment to avoid certain death. Bed rest can restore hit points equal to your level per day, twice that if you spend all day doing nothing but rest plus more if attended by someone with the Medicine skill.

Diseases and poisons have a Toxicity rating, which is the target number needed to resist it on a saving throw (physical effect or luck, player's choice) or a medicine roll to cure it.

Character advancement explains the process of gaining levels. Basically, Spears of the Dawn uses a goal-focused method of accruing experience points. Monsters and treasure don't have set amounts, instead the DM has a provided table of experience points the party should gain every gaming session based on their current level. PCs should not be granted experience for accomplishing trivial tasks with no real risk. Upon gaining the requisite experience, they gain the level immediately along with all of their effects.

Also, we get into skill points. In addition to the bonus skills granted by background and class, PCs gain 4 skill points at 2nd level and each additional level thereafter. They can be saved in between levels for the purchase of future skills. As for skills themselves, costs for new skill levels is dependent upon both the level to be attained (levels must be purchased in order, no jumping from 0 to 3) and whether or not they're class skills. Additionally, PCs can't gain Skill Levels of 2, 3, and 4 until they're 3rd, 6th, and 9th character levels respectively (meaning skill masters are also very high level).

Buying a cross-class skill from 0 to 4 can cost as 20 skill points, while raising a class skill you had at Level 1 at character creation costs 12 points. So long-term planning and taking your background and class into account is encouraged from a game mechanics perspective.

There's also some brief rules on levels beyond 10. Basically you reroll your 10 hit dice every level until you get a better result, along with skill points, but nothing else. You and the DM decided on a single special ability for your PC for each "bonus" level in line with your accomplishments:

quote:

Instead, the PC receives a single new ability appropriate to his nature and heroic deeds, chosen by agreement between GM and player. For persistent, always-available abilities, they should be roughly as strong as a warrior’s idahun. For abilities that can only be used once per day, they might be as strong as a fifth level spell or ancient song. Such legendary heroes should advance in unique gifts rather than simple brute accumulation of bigger statistics.

We get a one page explanation for converting to other old school rulesets. Due to the relative interchangeability of game mechanics in OSR games, the biggest hurdle is the skill system (remove it or alter it) and armor class (subtract or add 20 based upon whether its descending or ascending).

Ending our chapter's a 1 page quick reference cheat sheet of the most important and relevant rules for quick reference. I haven't played a game yet, but this (along with the chapter's relative shortness) is sure to greatly speed up gameplay.

Thoughts so far: The rules are very short, yet cover most of the stuff relevant to fantasy adventuring. It's close to the book's front, easy to navigate, basically everything done right.

Magic

Original SA post

Chapter Three: Magic

This chapter lays out the major features of 3 of the 4 classes of Spears of the Dawn: Griot songs and spells.

Before getting into each class, we have a general overview of how magic interacts with reality and how it's treated by the people.

Basically, magic comes in two varieties: the natural miracles of the griot and the marabout, and the manipulation of ashe of the nganga.

Miracles are fundamentally the product of natural law. The marabout appeals to spirits who have authority over certain aspects of reality, and in turn they change things to the marabout's favor. As for griots, their songs draw upon the social laws and cultural mores of their people, which are not just hollow concepts. Since marabouts and griots are drawing upon existing rules, they are easier to call up. Whereas a nganga must prepare their spells in rituals ahead of time, marabouts can call upon any spell they have access to in their spheres and a griot any song they know, the only limits being spell slots and inspiration points.

Ashe is different. It has nothing to do with the gods, spirits, or societies. It is more essential and fundamental to the make-up of this world, and typical used to alter and create such things. Curses, one of the nganga's most well-known spells, are effectively altering a person's supply of ashe to harm them in some way. Even skilled marabouts cannot permanently lift curses, due to the relative gap of difference between ashe and spirits. And those who are born with the potential to manipulate ashe are unable to control their powers effectively without tutoring under a more experienced user. It is for these reasons that it's distrusted among many religious people, who believe that it can sever the connection between mortal and spirit. It is also why many of these same people tolerate ngangas in their villages, to better counter the magic of evildoers of their kind and help train latent "witches" so that they don't accidentally curse their own friends and family.

Between the griot songs and marabout and nganga spells, there are 110 powers to choose from, and we'd be here all day if I outlined them all. Instead I'm going to do a general overview of the classes and spells, pointing out particularly interesting ones.

Griot Songs

Griots are experienced in the art of songs, near-magical chants and orations which can inspire and enlighten others with newfound truths, and fell wrongdoers with judgment. As judges of the deeds of mortals, griots' powers are not constrained by any overarching code, and thus can use their songs as they see fit (although certain conditions must be met for some songs).

Despite being in the magic chapter and earlier lumped in with marabout spells, griot songs aren't technically magical, and thus aren't affected by magic wards or dispelling effects. In fact, many of the griot songs can be seen as entirely mundane, and can just as easily stem from them pure skill. I actually like this variation. It leaves the griot in a sort of nebulous state as to how much they're calling upon a greater power, and how much of it is them being just that good.

Also, unlike spells, griot songs can only be interrupted by an attack which would render the griot unconscious or dead.

There are 22 griot songs to choose from, 8 minor, 8 great, and 6 ancient. They are generally divided into praise-songs, which buff up the griot's allies with bonuses of various kinds; Remembrances, which are sort of like bardic knowledge in that the griot gains insight into a certain situation; songs which don't fit into either category.

Overall, griot songs are pretty sharply focused in comparison to spells. They generally enliven allies, reveal knowledge, and bestow mental and emotional effects upon enemies. Still, they're pretty useful to have in a party.

Griots can also scribe their songs into large books, which can take many months to complete. The most powerful griot songs can encompass multiple volumes, and all whose workings only grant true knowledge of the craft to fellow griots.

The minor songs are small, minor effects which won't do much by themselves and are most effective in conjunction with other actions. The praise-songs grant minor bonuses to skill checks (Praising the Artisan's Hands), attack rolls, armor class, and the remembrances invoke various songs, poems, and legends to remember simple words in a foreign language (Remembering the Correct Words), common customs, and historical facts (Remembering the Old Kings). The sole offensive song, Condemning the Wicked Man, is a verbal castigation which deals damage in the form of sapping their fighting spirit (it can't strike someone dead for this reason).

Great songs are overall more powerful. They include inspiring words to get allies to shake off mind-control spells (Encouraging the Darkened Mind), convincing both sides of a conflict to temporarily disarm for a minute (Compelling the Stillness of Spears), make the subject of a song viewed more favorably by listeners (Praising the Wise Leader, favored by heads of state for this reason), and verbal accusations of horrific crimes which remove protection of the law temporarily (Condemning the Miserable Outlaw)! This last one's quite powerful, as crimes committed against that person during the song's duration will not be reported or begrudged, as it seemed perfectly justified to witnesses at that time. This makes griots the perfect assassins.

One song I like, Remembering the Spears of Heroes, allows the griot to determine the properties of a unique or magical items by consulting multiple heroic legends with fabled artifacts to narrow down which one it might be.

Ancient songs are few (6 instead of 8), but all very powerful. Absolving the Unjustly Accused forces a group of judges to not find it in their hearts to condemn or punish someone on a failed Mental Effect save. Praising the Unconquered Hero is a once per day song which grants temporary hit points and allows the target to reroll all attack rolls and skill checks, taking the better result, and lasts until the end of the current or next battle. Singing the Path to Glory is the griot being so knowledgeable of the land and its people that they can divine the fastest route to a particular important individual (whose identity is not being kept secret).

Condemning One Worthy of Death is not the most powerful supernatural attack effect-wise, but it's a very cool ability. The griot issues such a scorching condemnation to a person that their very skin peels away at revulsion of their crimes and their bones jut out, seeking to tear themselves free from such a terrible person.

Marabout Spells

The marabout is one of the two Vancian caster classes in Spears of the Dawn. Whereas a nganga must prepare their exact spells ahead of time, a marabout can cast any spell they know within their Spheres, provided that they have remaining spell slots to use. The marabout has a greater list of effects to choose from than the griot, 40 spells total instead of 22 songs. However, there are only 5 spells per sphere, one for each level. This means that at 1st level a marabout can really only cast 2 spells, while at 9th level they can cast from a selection of 25 spells.

As mentioned before, a marabout's Spheres represent their alliances with certain spirits, with the favored sphere representing the strongest connection and bestowing them a unique Gift in addition to the spells. Marabout do not have to pray or meditate for their spells, or directly communicate with the spirits. Their favor manifests in subtle signs of approval and disapproval. Oddly enough, a marabout still retains access to spheres even if they go against the taboos and holy codes of their faith. Many scholars and theologians debate why this is: some theorize that the marabout's connection to them is too strong to break, others theorize that immoral marabout draw their power (knowingly or unknowingly) from the Gods Below.

A marabout usually must take at least one round's worth of action to cast a spell, and be able to speak to summon their spirits' aid. An enemy higher in the initiative order may hold their action to strike on the round of casting, which disrupts a marabout's spell. This action can work on ngangas as well.

So we have eight Spheres, all of them with very different effects. The kind of character your marabout can be, and their role in the party, is strongly shaped by the selection.

The sphere of Curing is straightforward, granting hit point restoration spells at 1st, 4th, and 5th level spells (the latter regenerates hit points per minute until they hit their maximum value), and curing disease and poison at 2nd and 3rd levels. As a favored sphere, it bestows immunity to all diseases. This is pretty much a good deal for any adventuring party to take, as the Medicine skill is not as immediate in its effects, and healing potions can get quite expensive over multiple purchases.

The sphere of Death grants power over the transition between life and death, the soul's passage from the mortal world of the land of spirits. Its spells involve granting the next damage roll its maximum value, speaking with the dead, taking on undead immunities and qualities, raising the dead (must be willing), and the ability to either create undead servants or damage the walking dead (both the same spell, Servants of Clay). The Gift allows the marabout to automatically stabilize when bleeding to death, and do the same to others suffering the same fate. Overall, a few of the spells are situational, but the maximum damage and resurrection are both very useful. This sphere might be good to take as an additional option later on down the line.

The sphere of Herding makes you good with animals. The spells granted allow you to speak with animals, enchant a staff with the power to scare off wild beasts, grow long savannah grass which is edible and can feed ten people per class level, transform into a beast and gain their qualities (lose spellcasting ability for duration), and the ability to summon horned warrior spirits to fight by your side. Its Gift increases the marabout's Strength or Constitution modifier by 1 point. Overall a situational and underwhelming sphere, although I can see some min-maxers incorporating the gift for some battle-priest build.

The sphere of Passion is all about manipulating the emotional state of others and getting them to do what you want. Its spells include a minor bonus on social interaction checks, have a target treat you as a trusted friend for one day per level, fill a crowd of listeners with a certain strong emotion, fill a target with grief and make them unable to perform actions, and cut a target's emotional bond with the most important thing in their life indefinitely (or until the curse is dispelled), filling them with apathy towards the subject. The Gift increases the Marabout's Charisma modifier by 1. The spells have quite long durations (even the shortest-lasting grief-based one lasts 1 round per level), which can make them very useful in games which aren't just straight dungeon-crawling. And even then they can be used to turn certain monsters into brief allies.

The sphere of Spirits makes the marabout skilled in dealing with the denizens of the spirit world. The spells include the creation of a spirit ward which hedges out spirits and potential possessions, a magical light which reveals the auras of magical effects and invisible creatures, a short-term suppression of curses (1 round per level), the ability to summon a spirit ally to help with tasks for 1 hour per level, and the ability to deal damage to spirits by rebuking their presence. The Gift grants the ability to speak with all spirits regardless of language barriers, +2 on social rolls with them, and the ability to see even normally invisible spirits. This is a very useful sphere all around, from levels early to late.

The sphere of Sun grants you the favor of that celestial ball of light, to channel a little bit of its great power to work your will on the world. Its spells allow you to make a ranged fire-based attack, granting you and your allies tolerance of very cold and very hot temperatures for several hours, imbuing light into a weapon to make it magical and glow and deal fire damage, a burst of light which reveals all hidden people and objects (people with Stealth skill level 3 can still hide), and the ability to conjure pillars of burning light to strike down your foes. Its Gift allows you to see perfectly regardless of lighting conditions and radiate light in a 60 foot radius at will. A very offensive-based sphere. If you're a Sun Faith marabout, you must have this as your Favored Sphere, but you gain an additional spell level per day for your devotion, so playing a Sun Faith spellcaster can be a very good choice (especially early on, when you don't have too many spells).

War governs violence and wrought iron. It is one of the best spheres for several reasons. One, its spells are relevant to a very important aspect of D&D retroclones: combat. Two: its spells are overall long-duration (3 out of 5 have 1 minute/level) and affect multiple allies (3 out of 5 affect allies within 30 foot range of the marabout). Its spells, predictably enough, grant bonuses on to-hit rolls, fill enemy opponents with fear (penalty on to-hit rolls and might flee), bonuses to armor class and reroll the damage rolls of mortal blows directed at them, the ability to restore hit points via successful attacks, and the ability to make allies share the best attack bonus of the person within their ranks. Its Gift grants a +1 on to-hit rolls with a single chosen weapon.

I haven't compared them side-by-side yet, but a War sphere marabout might just be able to fill in for a Warrior. Unlike 3rd Edition they are not so powerful as to make them feel useless, but the spells alone can buff up the marabout and their buddies to fight well in combat. The Warrior has more skills, better saving throws and hit points, but the marabout can easily get a near-equal attack bonus with buff, plus spells to boot!

The final sphere, Water, governs the streams, lakes, and oceans of the world. Spells include the ability to conjure a stream gushing out gallons of water, the ability to grant the marabout and their allies the ability to swim and breathe underwater, conjure a thick cloud of rain which hinders enemy visibility and movement, creating a snaking arc of water in mid-air which can block enemy movement and missiles (can be shaped by marabout, making it great for battlefield control), and the ability to instantly teleport themselves or a small barge across connected bodies of water. Its Gift grants the ability to swim in water as fast as they walk, and the ability to breathe in it. The early spells are very situational and not that great, but the later ones are very useful.

We also get another sphere, the sphere of Blasphemy. It available only to worshipers of the Gods Below, beings universally feared among the Three Lands for their wicked ways and fell powers. They are so named because its believed that they live deep in the bowels of the earth. Umthali (snake-people), Eternal cultists, and marabout desperate for power pledge themselves to them.

Basically, the Blasphemy sphere cannot be normally selected. Those who pledge allegiance to the Gods Below gain it as a bonus sphere, even if they're not a marabout (in this case they cast as a marabout of equal level). They must regularly perform hideous rights to please the Gods, and will be rewarded well in their afterlife. Those who seek to back out of the deal receive nightmarish visions of ghastly torment by said Gods, supposedly what awaits them in the spirit world once they die. The spells included grant the ability to summon worms to eat at the victims, force witnesses to be unable to communicate in any way about a certain action or event, manipulation and excavation of stone and earth, stunning targets by using foul curses, and summoning swarms of soul-eating worms. It doesn't have a gift, but those with this sphere gain bonuses against divinatory magic which might reveal their true nature.

As it's a free sphere, there's no downsides mechanically to taking it. However, the Gods Below are very much definitely evil people, and worshiped by those who'd be enemies of the Spears of the Dawn and most people of the Three Lands.

Nganga Sorcery

Nganga's arts and training are quite demanding. In addition to years of training under a tutor to harness their magic properly, they often must gather materials and resources to properly cast their spells, be they ritual magic components or handheld objects for nkisi spells. Most nganga are lone people of a few souls in villages, rarely attaining heights of greatness. They make their living as charm-makers and curse-breakers, mostly concerned with staying in people's good graces. The most powerful nganga live out in the wilderness, far from prying eyes to better discover the lost lore of forgotten ages. And there is the land of Lokossa, where the mightiest ngangas serve as the heads of noble families, with the mighty Ahonsu (sorcerer-king) ruling them all absolutely.

There are two kinds of spells nganga can cast: ritual spells, which face no per-day limits but have lengthy casting times and sometimes expensive material costs. And nkisi spells, more immediate magic stored in minor handheld objects upon the nganga's person.

Nganga can forage the wilderness for 10 silver ingots worth of materials per day for specific ritual spells (they can't just be gathered and stockpiled over time), while some magic requires a physical connection to a target in order to work (well-worn clothes, a lock of hair, blood, etc).

A nganga's spells per day are represented by their nkisi. They can prepare additional slots with a successful DC 6 Occult/Int roll, +2 for each additional spell. A failed roll means that all the prepared spells go off with the nganga as the target upon the completion of spell preparation. It is for this reason that most nganga do not exceed their limits except in times of greatest need.

A nganga has 48 spells, both ritual and nkisi, 5 per spell level each up to 4th level, and 4 each for 5th level spells.

Ritual spells are quite varied in effects. Their casting times can last anywhere from 30 minutes to a whole day, and some require material costs ranging anywhere from 30 to 5,000 silver ingots. Rituals tend to be more powerful and varied than their equivalent nkisi spells, for obvious reasons, with some exceptions. Rituals can involve the lifting of curses (which have their own unique game mechanics), creating minor magic items which grant bonuses on various rolls (they usually fall apart after several uses), the ability to call forth a spirit minion or assassin for service, communicate with other people via dreams, place curses on other people which bestow penalties to certain rolls until they're lifted (or a long enough time passes), distant scrying, fast travel to distant locations by being picked up by the wind, and more!

Nkisis are much more limited, but have the benefit of quick casting. Nganga nkisi tend to be more offensive-oriented in comparison to marabout spells, and some of them are quite powerful. Nkisi of the Deadened Mind, for example, is a 1st-level spell, but can turn a target into a brain-dead slave for one day per level! Granted, it's the most powerful of its level, but still. Some of the more interesting spells include Nkisi of the Broken Shadow, where a target is attacked by their own shadow; Nkisi of the Crimson Nail, which painfully pins a target to the area they're currently in; Nkisi of the Invincible Wall, which fills an ally with a short-lasting surge of overwhelming mystical force which grants a +4 bonus on their next roll; Nkisi of the Sundered Spell, which can act as a counter-dispel against enemy magic; and Nkisi of the Walker at Night, which allows the nganga to teleport between areas they're familiar with by stepping into the shadows and exiting into the place of their choice.

Ngangas are easily the most versatile in their powers, but are limited by potential costs and lengthy casting times, the necessity to prepare spells ahead as opposed to selecting which ones they want to cast at the moment, and class limitations (physical frailness combined with the inability to wear armor). The fear and apprehension they inspire in others is more of a role-playing limitation.

Thoughts So Far: I really like how the magic system interweaves with the setting as opposed to just feeling tacked on, like in the settings of other retroclones. Not only are the differences between each class explained, knowledgeable people in the game world recognize this and act accordingly. Leaders seek to stay on the good side of griots, villages turn to ngangas to lift curses, marabout can enter into new alliances with spirits over time and expand their power. Crawford put a lot of thought into this, as he did with the rest of the book's chapters.

Next time, Chapter Four: The Three Lands! Finally we get to the setting!

The First of Three Lands

Original SA post

Chapter Four, Part One: The Three Lands

Apologies for the delay, but stuff was occupying my time. This chapter's a big one, too big for me to cover everything, so I'm going to handle it in two segments.

A Brief History

In ages past, the Old Kings ruled great nations between the western sea and the Weeping Mountains of the East. Two centuries ago the Nyala Empire waged war against the eastern kingdom of Deshur, forcing its populace to retreat eastward, into mountain temples built long before the ages of men. It was there the Deshurite King discovered the forbidden arts of the Gods Below to ensure that his people would survive and take revenge on their enemies. It was here the first Eternal were created. They were called this by the living because they never really died. They could live deep in the deserts without food or water, their flesh still and unaging with no breath of life. They lived strange pantomimes of life, only a few among their dread lords containing the skills and memories of their former lives, ruled by a dread Eternal King.

They ventured west, bringing the Three Lands into a conflict called the Long War, so named because it lasted 150 years. Only the internal quarrels among the Eternal and the need to hold onto existing territory did they not conquer the Five Kingdoms. Even some among the living began to worship the Eternal as new gods, forming cults and secret societies motivated by the promises of power and immortality.

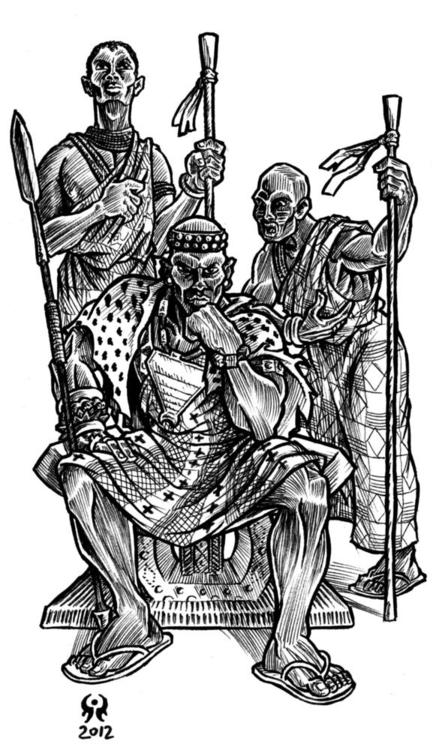

Forty years before the current era did Emperor Kaday of Nyala realize that the Five Kingdoms must be united if they were to drive back the Eternal. He formed a binding alliance with independent and former Nyalan provinces of Sokone and Kirsi by promising them autonomy, earning their soldiers yet angering the Nyalan nobles who lost their traditional holdings. But it worked, for they led a unified army into the east which even the Eternal could not hold out against. Emperor Kaday strode alongside the Sorcerer-King of Lokossa at his left, and the greatest Marabout sages of the Meru on his right. Before him rode the iron lancers or Kirsi, and at their flanks marched the sea-wide legions of Sokone with the best equipment and training their gold could buy. They stormed the walls of Desheret, the capital, and the Emperor died in battle against the Eternal King, who was wounded and taken to recover deep into the Weeping Mountains.

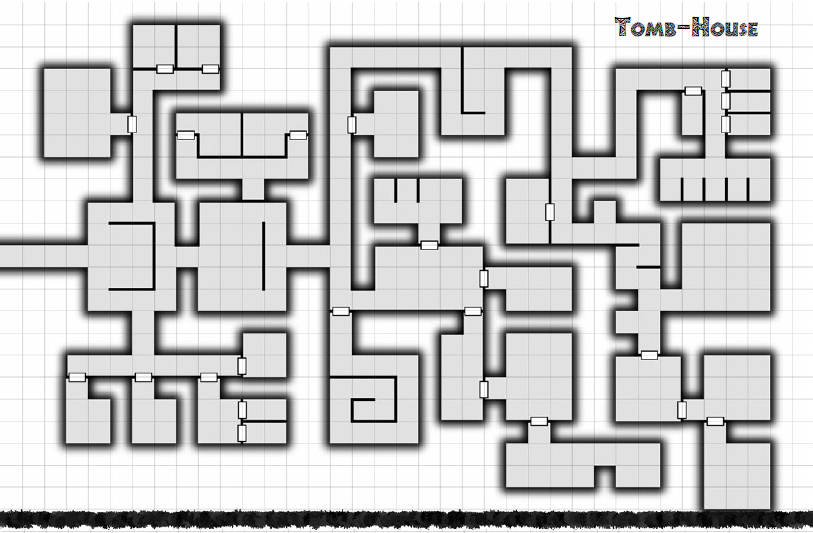

The Long War was finally over, the soldiers returned to their homes. But the Eternal still lingered, in hidden wilderness tomb-houses and supported by loyal cultists. The Spears of the Dawn were formed among the best soldiers of all the nations to hunt down these remnants, promised freedom, gold, and other privileges as long as they performed their duty. Nowadays the Spears have little official support, eventually becoming but a tradition upheld by individual teachers.

The Eternal and the Spears

We get short blurbs further detailing the Eternal and the Spears of the Dawn. Basically Eternal are mortal spirits trapped in their own dead bodies, losing most of their reasoning and mental faculties save for a few powerful individuals. They are hierarchal, being ruled by former nobles and spellcasters among them. Despite the benefits of undeath, all Eternal cannot heal naturally, and must regularly consume living human flesh to avoid further desiccation. Secondly, they're all driven a hatred of all living things which can only be held in check with sufficient willpower. Thirdly, and most horribly, they can never know the peace of true death. Even if hacked apart and stomped into a bloody paste, their minds will still continue on in a red haze of never-ending confusion and agony. Their spirits will always remain in this world, never moving on.

The Spears of the Dawn were formed by Emperor Kaday and an alliance of the Five Kingdom's best soldiers. In exchange for venturing out and destroying the Eternal remnants in the time of tenuous peace, they'd be promised riches and land once their mission was finally done. In the meantime, lesser nobles would show deference and respect to Spears and do their work without interference. The Emperor died before he could fulfill his promise, and the governments never bothered to give them land, but the Spears remained true to their cause. Cleaning out Eternal tombhouses was dangerous, but they could earn a comfortable living selling their plunder, and it was preferable than stealing from peasants or fighting one's fellow man. Over time they expanded their efforts beyond the Eternal, defending the common folk from all manner of beasts, bandits, and other dangers of recent years.

Spears of the Dawn are exempt from the lesser laws of the Five Kingdoms. They can get away with more troublemaking and minor violence than any commoner, and are not expected to conform to the traditions of their gender or social class. Said tolerance has its limits, as theft, murder, treason, and major crimes will be punished, but a Spear who can demonstrate and justify his or her actions can stay the wrath of a noble.

Life in the Three Lands

Although each kingdom has its own culture, traditions, and history, there are some general trends which can be applied broadly. The setting is divided into five kingdoms discussed in the first chapter, along with three general geographic regions known as the Three Lands: the Green Land, the Yellow Land, and the Black Land.

All of the Lands are hot in climate. The Green Land is in the west, comprising the meadows and forests of Nyala, the marshes and fields of Western Sokone, and the rainforest of Lokossa. The Yellow Land is much drier, comprised of the golden grass savannas of the Meru and the hills and badlands of Kirsi. The Black Land of the east is nearly impossible for humans to live in, so named for its ebony sands. Only among the banks of the Iteru River can living settlements survive. Eventually the sands give way to dark, craggy hill and the Weeping Mountains.

Basically, life in the Three Lands is feudal to one degree or another. Society is hierarchal, where those in power (be they nobles, ngangas, merchant families, or tribal elders) are in charge of overseeing the affairs of the majority, protecting them in exchange for service. Society is structured in that every person is expected to perform their role for the betterment of the community, and that trying to defy or escape this fate is selfish and puts everyone else in jeopardy. Even the Spears, who are regarded as remarkable people, are burdened with the tasks of defending the rest from the Eternal and other horrors. And while minor nobles might live lives of privilege, they must at least tend to their duties if they expect to hold onto their land and titles from rival groups and heads of state which in turn rule over them. In short, everyone must do their part.

The Three Lands place a high importance on politeness, even between different social classes. A Lokossan noble might "ask" the serfs when the harvesting of rice will be complete rather than ordering them into the fields, while the courts of Nyala are an elaborate web of "gifts" and "favors" where people ask and demand things in roundabout ways which might be imperceptible to outsiders. People who can't get along with their neighbors might eventually find themselves exempt from the laws and social contract of their town and village, and be forced to leave or fend for themselves. Overt rudeness is tolerated between close friends and family, because only kinsmen would speak so coarsely about each other. Rudeness between strangers and enemies, however, puts people at alarm, for it's usually a precursor to violence and when words can no longer settle disputes.

The author says that the DM should cut the plays some slack in the portrayal of their characters. Don't punish them for using modern protocals, and take their in-character words in the spirit that they're given rather than how they're conveyed. Fostering immersion in the setting is better accomplished by focusing on the NPCs and how to present them in the proper light. This is good advice!

In regards to family and marriage, relationships are expressed in terms of nations, clans, and families. Nations began as tribes which conquered or assimilated with their neighbors, until they reached a large-enough population and area that society transforms into the concept of the nation-state. There are some ethnic minorities and cultural holdovers which first and foremost refer to their tribe or clan, but most people identify primarily as being part of one of the Five Kingdoms.

Clans are more important at the local level, generally being shared descent from a famous figure, spirit, or important historical event. Clanmates are expected to provide food and shelter to each within reason, knowing that they would do the same for them. As a survival mechanism it encourages the richer members and farmers with good harvests to help their neighbors survive in hard times.

Gender and Sexual Orientation

Society is overall patriarchal. Men inhabit most positions of power, from governance to military to other important and prestigious decisions, and the eldest males of the families are in charge of being the "priest" for appeasing local and ancestral spirits (or the Sun in the case of the Sun Faith). Marriage is determined by a man paying a bride price to the woman's family, and polygamy is common among society's elite of both the Sun Faith and Spirit Way religions. Divorce is permitted, and although it's officially initiated by the man, poor treatment and abuse of a wife can be grounds for it. The offending husband in this case is often jeered by villagers for wasting his wealth and being a jerk. Adultery is a fair reason for dissolving marriages, with custody of the children usually going to the wronged party.

In regards to sexual orientation, it is regarded as something people do and not a part of a person's identity. Even people who exclusively prefer partners of the same sex are expected to marry the other gender and raise a family, with discreet same-sex relations being overlooked as long as they can provide for their spouse and children. Homosexual and bisexual people are not seen as monstrous or evil, rather they're viewed as excessively lustful. Same-sex activity is not illegal, but on the other hand they are not recognized as valid marriages.

Despite having sexist and homophobic elements, there is a degree of social change going on in the Five Kingdoms. The Long War drained many males into military service, forcing woman members of the community to step in to fill now-empty occupations. Spears might be exempt from societal expectations and regarded as strange people, but heroic and virtuous men and women can serve as an example to others and cause people to reconsider their old traditions and preconceptions. Even Lokossa has some concessions in regards to sexual orientation and gender; men and women who perform roles traditionally regarded for the other gender can be socially and legally considered that gender from then on out.

This isn't unique in Crawford's work. He often has sexist and homophobic elements in his campaign books, enough to provide conflict for groups who want it but not so restrictive that being anything other than a straight male is a constant obstacle. Instead of having things be hopelessly regressive, PCs can help change things for the better, and being Spears can exempt them from the traditional restrictions of society.

I think that this is an overall good way of doing it, although I still think that such things should be wholly decided by the group. Players who deal regularly enough with sexism and homophobia in their real lives might not want it intruding into their escapist fantasy.

Crime and Punishment

We get some blurbs on crime and punishment. Basically, most lands once and currently governed by the Nyala Empire have their legal codes descended from the old laws, with some degree of change between local ordinances. Petty crimes such as theft, insulting a noble, and drunk and disorderly are punished with small fines and a few blows of the rod, with greater crimes such as destruction of property might result in financial reparation or private beatings (public beatings are deemed harsher due to the humiliating aspect). Capital punishment is reserved for the most heinous of crimes, such as murder, rape, and the destruction of holy places (an intentional and violent insult to the community's spirits).

Slavery is considered barbaric and illegal everywhere except Lokossa, where it's reserved for criminals and social malcontents. It used to be a widespread practice in the days of the Old Kings, but the Long War forced all hands to fight for survival until it led to a near-total diminishment of the practice. The depletion of people at the end of the Long War has put an increased demand on labor, and disreputable people powerful enough to operate beyond the reach of the law have dragooned people into workshops, timber camps, and vast farms. Slavers are technically kidnappers and criminals, and the slaves are chosen among people who have few people to care for their fate (the exiled, criminals, foreigners, etc). However, they are hated by the authorities even if they can't do much to stop them, and heroes and Spears who put a violent stop to their operations are almost never legally prosecuted for this.

Food and Drink

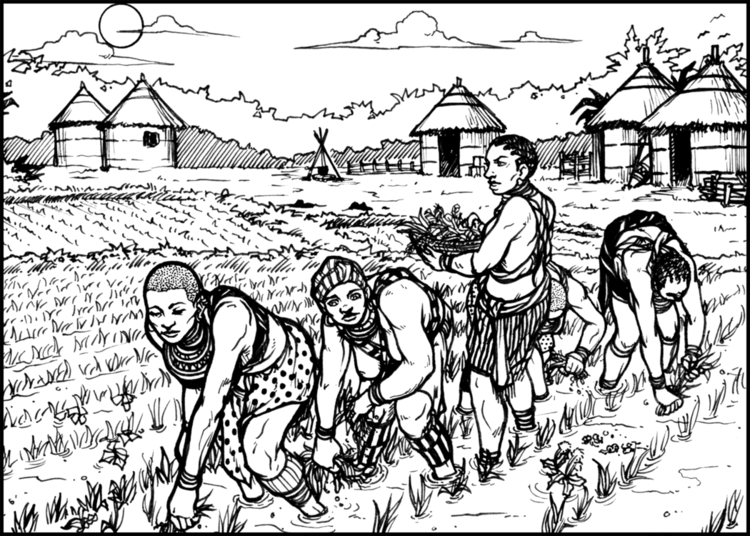

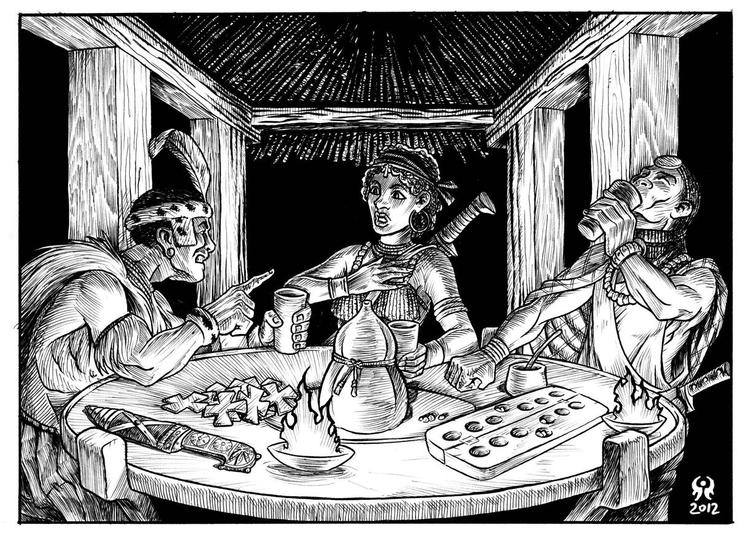

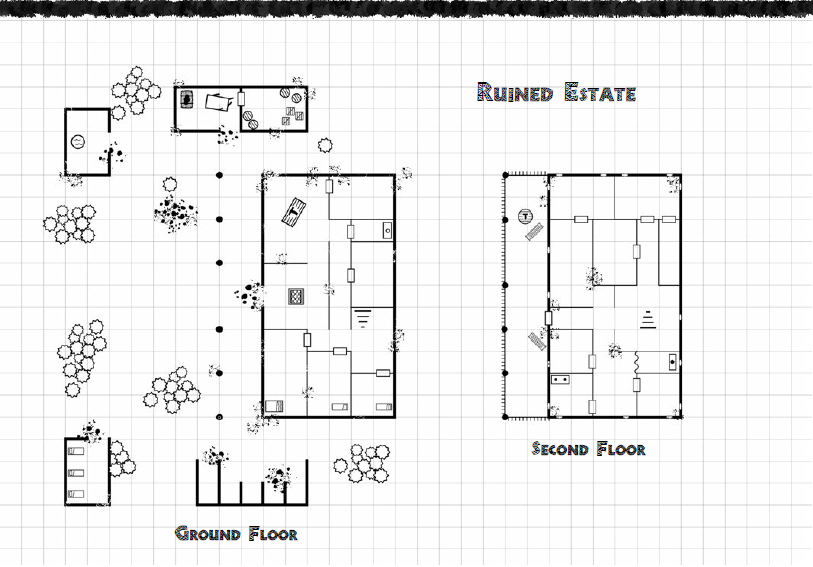

*note the Mancala board game in the lower right.

The most popular food and drink in the Three Lands are wheat, maize, rice, water, and alcohol. The three grains are prevalent in the lands of Kiris, Sokone, and Nyala, with wheat and corn most prevalent in the north. Taxes are usually paid in grain. The Meru's entire diet revolves around their herd of cattle: meat, milk, blood, and entrails are usually eaten raw in honor of their ancestors who were too busy fleeing the Eternal to set up cookfires. Cooked food is tolerated, to an extent, more for women than men as it's seen as "unmanly." Lokossa's staple food is the cassava, the woody root of a shrub grown in clearings which must be carefully prepared, for eating it raw can cause permanent nerve damage due to being laced with cyanide in its natural state.

Water, wine, and fruit drinks are the most popular drinks of choice. Palm wine is favored in the Green Land, while beer is more popular among the well-to-do. Fruit drinks are distilled from bananas, mangoes, melons, plantains, coconuts, dates, and whatever else can be found (grapes are unknown). The Meru have no known alcoholic beverages.