Mouse Guard RPG by Kestral

It's Not What You Fight, It's What You Fight For

Original SA post Mouse GuardMouse Guard is a game by Luke Crane based on David Petersen's award-winning graphic novel series of the same name. In Mouse Guard, players take on the role of anthropomorphic mice who live in an enchanted forest in perfect harmony with –

Oh god what –

What is this I don't even –

All right, let me start over.

It's Not What You Fight, It's What You Fight For

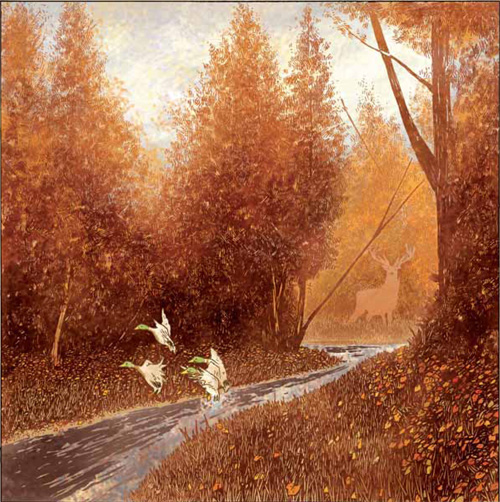

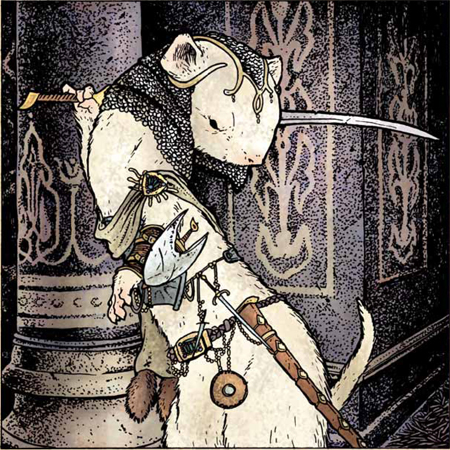

Mouse Guard is Luke Crane and David Petersen's game about mice with swords, how the world tries to exterminate them, and how they simply refuse to die . It is essentially the

version of Redwall, replacing most of the loving descriptions of food and singing with vicious animals killing mice while even more vicious politicking does essentially the same thing. You can tone this down a bit if you're playing with a younger audience – and Mouse Guard has become a big hit for the “gaming with kids” crowd – but it's a serious game at heart.

version of Redwall, replacing most of the loving descriptions of food and singing with vicious animals killing mice while even more vicious politicking does essentially the same thing. You can tone this down a bit if you're playing with a younger audience – and Mouse Guard has become a big hit for the “gaming with kids” crowd – but it's a serious game at heart.

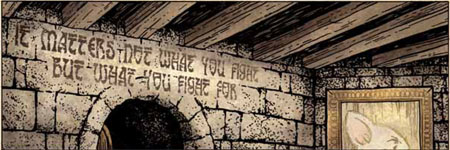

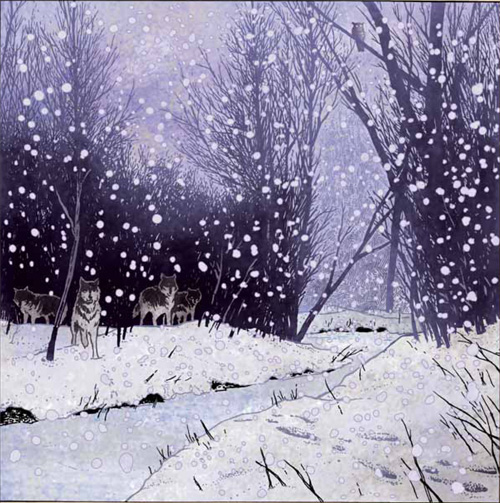

The setting of Mouse Guard is what you might call “low fantasy.” There is no magic, few if any traditional fantasy elements, and the world operates according to well-understood natural laws. The exception, of course, is that there are sapient mice, and they've established what amounts to a medieval society in the middle of the forest known as the Territories. The mice of the Territories have created a quasi-military force - the titular Mouse Guard - to elevate themselves from their place at the bottom of the food chain and overcome the forces of nature. The Guard exists in an ambiguous social area somewhere between knights, Tolkien-esque rangers, and FEMA agents. They are thankless heroes who exist outside of mouse society to better serve it. When something has gone seriously wrong in the Territories and time is of the essence, members of the Guard are dispatched to put it right – even at the cost of their lives.

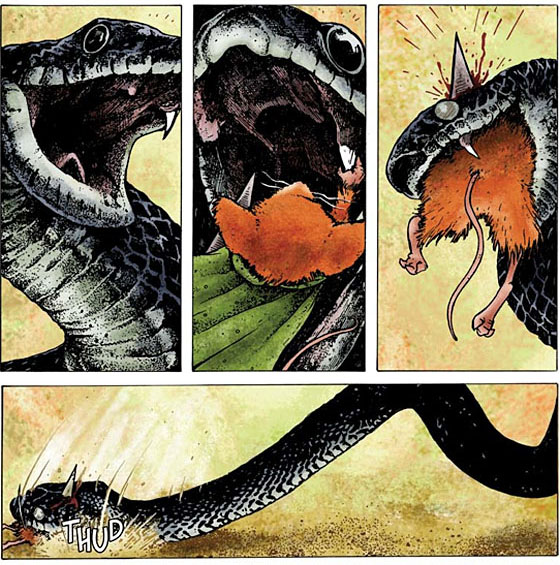

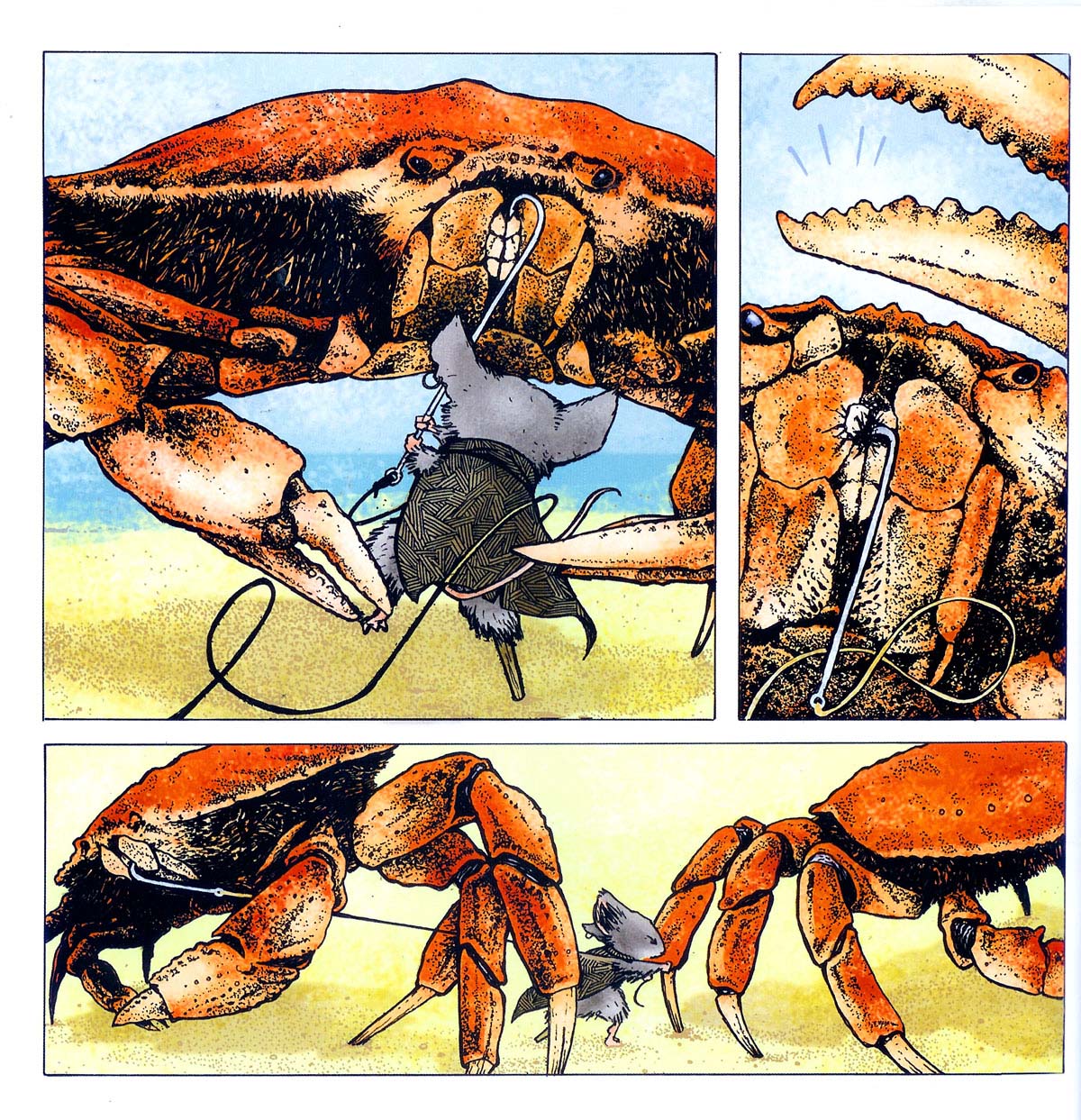

But despite their technology and fledgling civilization, they're still mice: when you're three inches tall a snake is a creeping horror out of Lovecraft, hawks are nigh-invincible dragon-like predators, a swollen stream is a deadly impassable torrent, and a good rain storm can annihilate farms and wreak enough havoc on your communities to put Katrina to shame. One of the distinctive features of both the comics and the game is the sense of scale they impart. You are playing small creatures in a huge and hostile world, but highly motivated ones. With swords.

Mouse Guard is a 300-page corebook in twelve chapters. Like Burning Wheel , the previous big game that Luke Crane wrote and the one for which he's best known, a lot of that pagecount is devoted to telling you how to play the game right rather than describing mechanics. I could condense this into perhaps four or five moderately sized posts, but I'm going to be honest: I love this game and think it deserves the best coverage I can give it. I'll be doing one post per chapter, supplementing the book's content with asides from the comics, commentary on the text and examples of play. Here's what we can expect going forward:

1.Introduction – A “What is Roleplaying” chapter done right.

2.The Mouse Guard – A history of the guard, what those words on the character sheet mean, and sample characters.

3.It's What We Fight For – Beliefs, Instincts, Goals, and the Reward Cycle.

4.The Mission – The framework of a session, obstacles, the GM's Turn and the Player's Turn, and a sample mission.

5.Resolution – How to roll dice, what happens when you do, and the Conflict system for when a snake tries to eat you.

6.Seasons – The framework of a campaign, seasonal missions, weather, and the Winter Session for Pendragon fans.

7.The Territories – The eight settlements of the Mouse Territories, the wilderness between them, and how it tries to kill you.

8.Denizens of the Mouse Territories – Mice templates, bloodthirsty weasels, a literal bestiary, and how to fight Bearzilla with science.

9.Abilities and Skills – A very clever advancement system, obstacles for skills, the Nature of mice and other creatures, and what those numbers on the character sheets mean.

10.Traits – How to be a special snowflake.

11.Sample Missions – Quick character templates, snake attacks, a mail delivery gone horribly wrong, and more evidence that snapping turtles are dicks.

12.Recruitment – At long last, how to create a character.

Chapter 1: Introduction

The introductory chapter is short and doesn't tell us much about the game, but there's a few interesting notes to be made regarding the way it presents information, the basics of the system, and the Mouse Guard canon.

Mouse Guard starts off with the traditional “What Is Roleplaying?” section, along with definitions of basic gaming terms. We've all read these a hundred times, but it's worth pausing here to note something about the way the text is written. A lot of RPGs include an Intro to Roleplaying section without thinking about it. It's a perfunctory effort, something you do because it's what you've seen other games do, and as a result they tend to do a poor job of imparting what is actually really important information to someone who has genuinely never seen a roleplaying game before and has nobody “in the know” to introduce them to the hobby.

Luke Crane has taken a lot of flak for the authorial voice he uses in Burning Wheel because some readers find it patronizing. When Luke writes Burning Wheel text, his tone reflects the fact that he knows the majority of his readers will be RPG veterans who have years of ingrained habits which are incompatible with good BW play. Luke's not trying to teach people what an RPG is, so the wordcount he'd otherwise use for that is spent on grabbing you by the lapels and shaking you until the bad habits fall out. For Mouse Guard, Luke assumes that his readers are new to the hobby, so the style is deliberate, instructional, and doesn't waste a word. If you read it out-loud it sounds a lot like how you'd teach a bright kid to perform a complicated task. In fact, that may be exactly what he's doing: the Mouse Guard comics have a large young adult audience, and the RPG was Luke's attempt to reach a more “mainstream” audience than the niche Narrativist game that is Burning Wheel.

The result is a short Introduction chapter that actually conveys all the vital information about what roleplaying is, how Mouse Guard fits into the hobby, and what some of the basic “best practices” in roleplaying are. Here's a section I wish had been in the AD&D books I played as a kid:

Mouse Guard posted:

Taking Turns

As you're playing your character, be polite and respectful to everyone else at the table. If your character is angry, you should not use that as an excuse to be angry or mean to the other players. Make sure that everyone gets a chance to speak; make sure that everyone gets a chance to be in the spotlight. When someone has the dice and is about to roll, the rest of the table must be quiet and attentive. It's that player's turn to add to the story. Before he rolls, he gets to describe what his character is doing. Everyone stops, listens and supports him.

You'd think this sort of thing would be intuitive - basic, common-sense social niceties. But as grognards.txt and the Worst Moments in Gaming threads can attest, gamers are bad at common-sense social niceties. You have to wonder whether it would be different if AD&D and its successors spend more time on teaching people to play well with others and less time on grappling modifiers.

Getting off my high horse for a minute, we're also told that Mouse Guard is a d6 dice pool system with success counting. Tests involves rolling a number of dice equal to a Skill or Ability and counting the number of dice that come up 4, 5 or 6 as successes, attempting to meet or beat an obstacle number either set by the GM or by the successes of another character. What it doesn't tell you is that most obstacles are too high to be met by a single mouse unless they're a serious expert: teamwork is one of Mouse Guard's big themes, so you're going to need a little help from your friends.

Finally, we're given a short note on comics canon and Mouse Guard RPG canon:

Mouse Guard posted:

When designing and writing this game, I tried to take my inspiration and cues directly from the Mouse Guard comics. Comics and games are two different mediums, but I the rules for this game, I pretend that the comics are a game. I imagine the characters are controlled by players. This way, the action in the comics stands as a great example of how you can play the game.

There's a reason this is in here. Fans of the comics who pick up the Mouse Guard RPG may wonder why there's no mention of the mice being subjugated by Fox and Hawk back in the day, or of the Wythrasher sparrow cavalry. Aside from the fact that Legends of the Guard hadn't been written yet, my understanding is that Luke prefers a canon where mice and weasels are the “cultural” creatures in the Territories and may be the only sapient ones, but he acknowledges that not everyone shares his preferences. Some games are going to stick strictly with the RPG material, while others are going to trend the way the comics seem to and allow most birds and mammals some degree of intelligence and language, however obscure. If you want a veritable Dr. Doolittle menagerie of talking animals it's your call, but the game assumes that mice, weasels, bats, hares, and at least some old owls can speak. In short, Your Territories Will Vary.

Up next: a brief history of the Mouse Guard, and the elements of a character.

Edit:

Doc Hawkins posted:

You might be surprised at the kinds of people who are willing to play an RPG for the first time if it does not involve dungeons, hit points, scads of dice, etc., etc.

Like kids!

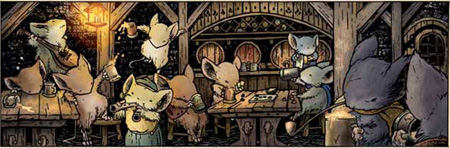

I mentioned above that Mouse Guard is big with the generation of roleplayers who are raising their own little gamers, or who are otherwise in a position to run games for kids like after-school programs. I've had the opportunity to run Mouse Guard for kids a few times, and it really does work. As long as they're old enough to read Redwall on their own and not so old that they've hit the "liking talking animals makes me uncool" phase, Mouse Guard can be a big hit.

I'm going to preach for a moment here. Roleplaying is a hobby that spreads from person to person; there can't be many tabletop gamers who got into it because they saw it on a comic store shelf. Every one of us who wants this hobby to thrive, to increase the diversity not only of its player-base but of its ideas, owes it to themselves to try to spread our love of gaming to others. Games like Fiasco and other short-form indie games are perfect for this because they're so accessible, and they're easily playable in an evening. Mouse Guard is a more significant investment, but the presentation makes it remarkably easy to pick up even for young kids. Do yourself and our hobby a favor and show other people how great this thing we do is, and run games for people , or give the books as gifts to people who might have an interest. Just because someone doesn't play now doesn't mean they never will - maybe they just haven't found their game yet.

The Mouse Guard

Original SA post

Chapter 2: The Mouse Guard

This is a chapter in two parts. First we're given a brief history of the Territories, the Mouse Guard and their fortress-city of Lockhaven. Next we're given the mechanical makeup of a character and how the PCs fit into the setting, but it's not until almost 300 pages later in Recruitment , the very last chapter, that we're told how to actually make a character. It's assumed that most people are going to play the sample characters from the pre-generated Missions, or pick a Template character to customize. This makes sense given the target audience, but for our purposes we're going to skip around a bit.

Part One: A Brief History of the Mouse Guard

Mouse Guard posted:

The Mouse Guard undertakes its duties as sacred obligations. If every mouse in the Territories turned their back on them, these selfless guardians would still spend their last breath defending and protecting them.

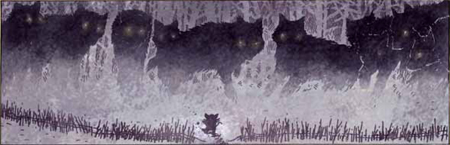

Back in the day, everything was terrible.

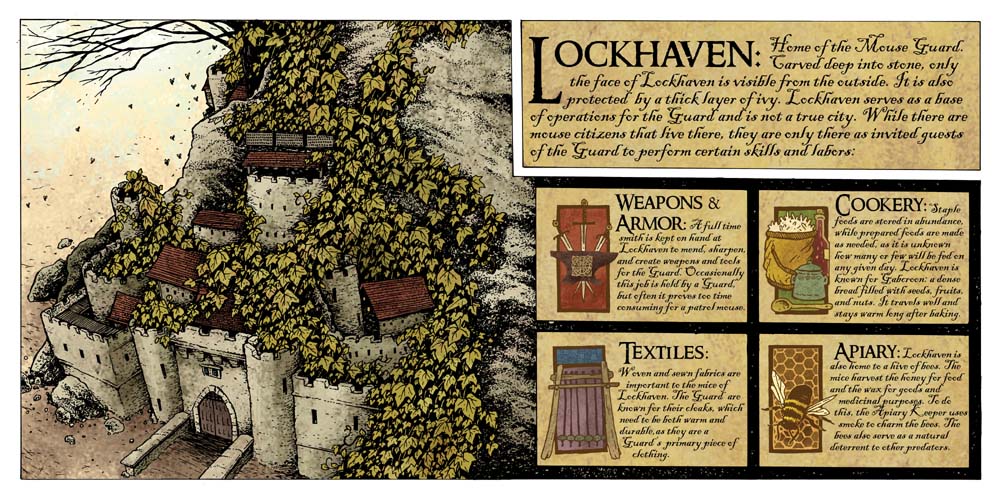

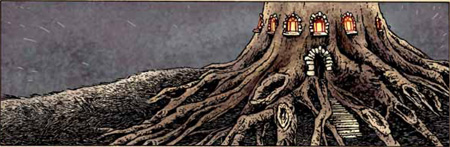

Mice were prey. They were at the mercy of the elements and the seasons. They held territory only so long as something larger and less friendly didn't happen along. They were, in short, essentially mousey . Eventually, a few mouse communities got fed up with being near the bottom of the food chain and decided to do something about it. Banding together, they carved out a hidden, defensible settlement in the face of a rock wall and began bringing in survivors. Surrounded by impenetrable stone walls, garrisoned by a volunteer militia and supplied by underground streams and deep granaries, it was the mouse equivalent of a well-built Dwarf Fortress settlement. They called it Lockhaven.

Over time, the Lockhaven mice discovered that they weren't the only ones to figure out this whole “civilization” deal. Other communities had sprung up throughout what were now known as the Mouse Territories. They were smaller and mostly less defensible than Lockhaven, but fiercely independent: they would never willingly incorporate into Lockhaven or abandon what they had built. As a sidenote, this is a theme of Mouse Guard: mice are both clannish and skittish, which makes their politics difficult. It's hard for them to build coalitions when their natures are telling them to hoard their resources and keep their heads low. This is mechanically supported, as we'll see later.

This sparked a debate as to whether to leave the outsiders to their fates or bring them under Lockhaven's control by force for their own good. Eventually, they settled on using the strength of Lockhaven to protect the rest of the Territories. Its militia blazed trails, patrolled the roads, delivered mail and supplies, fought off predators, and generally did the heavy lifting for the Territories, which began to thrive. They became the Mouse Guard. Over time, Lockhaven transformed from a city into a fortress dedicated to the logistical needs of the Guard.

As a final note on Lockhaven, we're also told that in addition to its vast stores of food, Lockhaven keeps a hive of bees tended to by dedicated apiarists who charm the bees with smoke. In addition to providing honey and wax, the bees can be unleashed on Lockhaven's enemies in case of emergency

.

.

Pictured above: Lockhaven. Not pictured: beeeeeeeees.

The Guard is overseen by a female captain known as the Matriarch who doubles as governor of Lockhaven. As the head of the only serious military force in the Territories, she's also something like the Secretary of Defense for the loose confederation of mouse city-states. The current Matriarch, Gwendolyn, is a canny old gal who has seen the Territories through a brutal war with the neighboring weasels of Darkheather (Oh yes, there are weasels - big flesh-eating weasels).

By treaty, the Guard are the final authority in the wilderness between cities, but they have no more authority in the settlements than any other mouse. The settlements are also supposed to help Lockhaven supply the Guard, which has grown larger than any one city can support, but they aren't obligated per se: technically the Guard is supposed to be self-sufficient.

We're also given the Guard's Oath which binds a mouse into service:

Mouse Guard posted:

We as Guard offer all that we are to protect the sanctity of our species, the freedom of our kin, and the honor of our ancestors.

With knowledge, sword and shield, we do these deeds, never putting a lone mouse above the needs of all, or the desire of self above another.

We strive for no less than to serve the greatest good.

The duties of the Guard take up a couple of pages, but it mostly consists of traveling the wilderness while maintaining trails, keeping the roads safe, delivering mail, scouting for natural dangers like predators or dangerous weather and less natural dangers like incursions from the weasel burrows in Darkheather. Since the Guard is ostensibly neutral, guardmice are also expected to act as mediators in disputes between settlements and sometimes between individual mice. Finally, the Guard maintains the Scent Border, a miracle of mouse science (yes, this is a thing) which keeps most large predators like wolves and foxes out of the Territories. As long as the Guard patch the Border up a couple of times a year the Territories stay free of their worst predators. This is good because as we'll see later, even a single fox can be a nightmarish threat to mouse settlements, and a bear who wants to claw your tree-city open for its delicious honey is basically Godzilla.

Part 2: The Patrol

Mouse Guard posted:

Hail all those who are able,

any mouse can,

any mouse will,

but the Guard prevail.

Now we're in to the mechanical guts of a character, although the text doesn't actually tell us that yet – it's going to be a long, long time before it shows us how to calculate the stats it describes. This is deliberate. The text makes it clear that it's going to introduce us to the game in a certain order that's supposed to make it easier to absorb. For RPG veterans this layout can get a bit tiresome, but it's a godsend for a newbie trying to grok the game on their own.

There's a lot of bits and pieces that go into a guardmouse. I'm going to summarize them here with more in-depth mechanical coverage later on.

-

Your

name

. Mouse names are vaguely Saxon or Celtic, like Ingrid, Brynn, Cale or Aengus, or taken from nature like Jasper, Lily, or Clove.

-

Your

age

. Here's where Mouse Guard gets a bit more fantasy: mice seem to live quite a long time, as their years are definitely measured the way ours are, and they live well past 60. A new recruit to the Guard is a

tenderpaw

, and they can join up between 14 and 18. Younger mice have a higher Health and more special Traits to play with, while older mice have a higher Will and more Skills.

-

Your

fur color

.

mouse racism

mouse racism

Seriously though, this has no mechanical effect whatsoever.

Seriously though, this has no mechanical effect whatsoever.

-

A

home

. There are eight major settlements in the Territories, and each of them gives a mouse who grows up there a leg up in certain Skills and Traits. A Lockhaven mouse might start play with the Armorer Skill and Guard's Honor Trait for free, for example, while a mouse from Sprucetuck might start out with the Scientist

Skill and the Inquisitive Trait.

Skill and the Inquisitive Trait.

-

Parents

. Like your Home, your parents give you Skills based on their profession, as we're told that “nearly every mouse in the Territories takes up his mother's or father's work.” Just as importantly, living parents give you a safe haven and source of supplies during play which can let you recover from adverse Conditions.

-

A

Senior Artisan

you apprenticed under as a tenderpaw in the Guard. The artisans pass on the skills necessary to keep the Guard self-sufficient(ish) to every new recruit. In play they're a source of yet more Skills and another source of aid and supplies.

-

A

Friend / Ally

. This is just what it sounds like. You've got a pal in or out of the Guard who will always try to help you if asked.

-

An

Enemy / Rival

. Someone's out to get you. This isn't necessarily a cackling villain or bloody-minded nemesis – it's more likely a rather ordinary person you've just managed to get on the wrong side of who persistently causes you trouble.

-

A

Mentor

. Someone in the Guard took you under their wing as a tenderpaw and showed you the ropes. Their personal take on a guardmouse's duties gives you one of their Skills, and they're probably going to be a friend for life and an ally in the Guard.

-

A

Guard Rank

from tenderpaw to to captain. Tenderpaws are rookies who would barely be trusted to tie their own boots if mice wore any; guardmice are the “line infantry” of the Guard; patrol guards are the grizzled sergeants who are occasionally trusted with solo missions; patrol leaders are guards who've demonstrated enough judgment and teaching skills to be trusted with a patrol; guard captains' roles are a bit ambiguous, but they seem to have authority over multiple patrols and act as advisors to the Matriarch.

-

A

Cloak Color

.

cloak racis – nevermind. Guardmice wear long, colorful cloaks of a particular cut both as symbols of their affiliation and to represent some aspect of their personality. If you've played

Dogs in the Vineyard

, it's basically the same as the Dogs' coat. No mechanical effects here, but it's a nice bit of color.

cloak racis – nevermind. Guardmice wear long, colorful cloaks of a particular cut both as symbols of their affiliation and to represent some aspect of their personality. If you've played

Dogs in the Vineyard

, it's basically the same as the Dogs' coat. No mechanical effects here, but it's a nice bit of color.

A brief aside. If it seems like there's a lot of non-mechanical “fluff” in what's supposed to be the character sheet section, you're half-right. Luke Crane writes games where characters' history and interpersonal relationships are a big deal, and the Mouse Guard comics are full of wise mentors and old friendships. Most of this stuff – with the exception of name, fur color and cloak color – should end up being relevant in play if your GM is doing her job.

The next three elements of a character might also seem like non-mechanical fluff. They're not. More than anything else, they are the character. Beliefs, Instincts and Goals are the subject of the next chapter, so for now we'll keep it short.

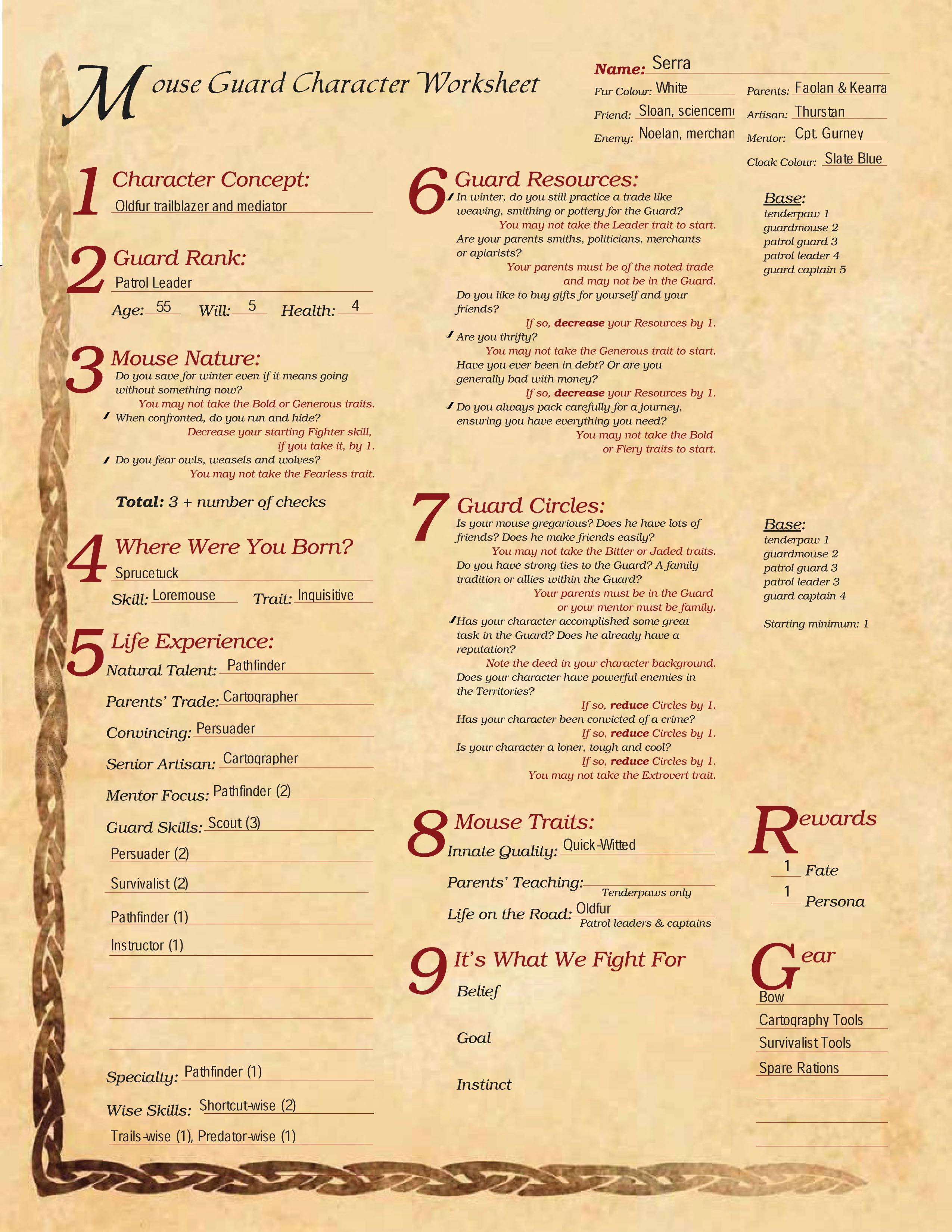

Every guardmouse has a Belief . Here's some of what the book has to say about these:

Mouse Guard posted:

A Belief is an ethical or moral statement that encompasses how the character views his world. It is also a way for the player to explore the Mouse Guard world.

In the very first issue of the comic, Kenzie tells Lieam his Belief, taken from one of the Guard's mottoes: “It matters not what you fight, but what you fight for .” This statement informs all of Kenzie's decisions. He is fighting for a higher purpose – not glory or personal success – but for the honor of the Guard and the safety of the Territories.

Beliefs are a huge deal in Mouse Guard. The book calls them an ideal you live up to, but there's another element to them that's a bit too “RPG Theory” for it to address in a text directed at new gamers: Beliefs tell everyone else what you want the game to be like, and in doing so they shape the play. More on that in Chapter 3. For now, just remember that playing your Belief results in an expendable resource that lets you fudge dice rolls.

Guardmice also have a Goal which is specific to the Mission they're on. Goals are a concrete objective for the Mission at hand which can be achieved in a single session, something like “I must find evidence that will determine if the grain peddler is a traitor or not.” Like Beliefs, addressing your Goal results in dice-manipulation bennies.

The final component of the “big three” character elements are Instincts. Here's the book again:

Mouse Guard posted:

An Instinct in this game is a habit or reaction. It's something that the character always does. If someone were describing your character, they'd probably mention this about him.

The example Instinct is ”Never delay when on a mission, but a lot of Instincts are more task-oriented or preparatory. For example, a character with the Instinct “Always keep an arrow nocked when I'm on patrol” bypasses all of those quibbling interactions we've all had at the table when an ambush happens. “I shoot the snake!” “No you don't, you're surprised, you need to draw an arrow first.” “Nope, see the Instinct?” “Ah-hah. Right, you shoot the snake.” When you play your Instinct, you get a reward similar to the ones above. Again, more details later.

Rounding out a guardmouse are the hard numbers, the stats and skills we expect to see on an RPG character. They are:

-

Nature

: This is a strange one. Every animal in Mouse Guard has a Nature score which represents their “natural qualities and tendencies.” The higher the stat, the more “like” that animal you are and the better you are at doing what your Nature compels you to do. Most animals have a static score, so an owl is always going to have Owl Nature 7 and be good at flying and quietly killing small furry things. Mice are different. By establishing civilization they are often working against their Mouse Nature, which compels them to

Escape, Climb, Hide

and

Forage

. The more “human” a mouse acts, the lower their Nature. The more “mousey'” they are, the higher their Nature. Extremes of either, however, can remove a character from play entirely when a mouse becomes either “too thoughtful and fixated on big ideas” (Nature 0) or too mouselike and settled (Nature 7) to be active in the Guard.

-

Will

: The all-purpose mental, social and willpower stat. You mostly roll this whenever you lack a more applicable Skill or to recover from certain Conditions. The older the mouse, the better their Will.

-

Health

: The all-purpose physical strength and well-being stat. Like Will, Health comes out when there's not an applicable Skill or during recovery. The younger the mouse, the better their Health.

-

Resources

: The “get things” stat. Resources represents your ability to acquire material goods through wealth, favors owed, an eye for a bargain, and so on. Resources is rated from 0 to 10.

-

Circles

: The “find someone” stat, and my personal favorite attribute in both Mouse Guard and Burning Wheel. Testing your Circles lets you create an NPC out of thin air. Failed Circles tests also have some of the most fun, story-driving consequences in the game in the form of the dreaded

Enmity Clause

, which gives you more than what you bargained for.

-

Skills

: Exactly what you'd expect. There are 34 skills in Mouse Guard, and you can start with up to 12 of them. Most are what you'd expect, like Hunter, Survivalist and Fighter, but there's also a fair mix of “craft” and social skills in there. Older mice start out with a pile of skills, but they pay for it with reduced Health and Traits. We'll be spending most of a chapter on these later.

-

Wises

: Technically a type of Skill, Wises deserve their own bullet. Wises are custom skills that represent specialized knowledge. You can test them to get information about the Wise topic, to create new information about it yourself, or to straight-up add a die to a related roll. If you have

Owl-wise

, for example, you could test it to say that the owls of the Territory prefer to nest in a specific area of the forest which you subsequently avoid.

-

Traits

: The quirks and attributes that make a mouse unique, like Determined, Fearless, Scarred, and Weather Wise. Traits can add dice to a roll or allow you to reroll failed dice on a test depending on the Trait's rating. Just as often you'll use them

against

yourself to build up a resource (“checks”) that let you get more out of your downtime. Again, Traits have their own chapter later on.

The rating of a stat or skill is the number of dice rolled when it's tested. Nature is rated from 0 to 7. Health and Will are rated from 1 to 6. Resources and Circles are rated from 0 to 10. Skills are rated from 0 to 6, with 3 as the baseline for reasonable competency.

Gear for a guardmouse is pretty simple. They're small and can't carry much, so you can have whatever fits into the Gear space on your character sheet, which is a roughly 2”x6” rectangle with a faint sketch of a guardmouse inside for the artistically challenged. Gear adds a simple +1D to any test where it's applicable. The only exceptions are weapons, which have their own special rules in the Resolution chapter.

We also get the first mention of Conditions in this chapter. By default a mouse is in Healthy Condition, but over the course of a Mission the consequences of failed tests starts to wear them down. Mice can become Hungry, Thirsty, Tired, Angry, Sick, and Injured depending on how a Mission goes, each of which penalizes certain rolls. Conditions all stack, so a mouse in bad shape can become incapacitated fairly quickly if they don't get some downtime.

The end of the chapter introduces the reward cycle of the game: playing your Belief, Goal and Traits for dice-manipulating bennies. I'm going to go into detail on these in the next chapter, so I'll skip this part for now for organization's sake.

Chapter 2 finishes up with character sheets for three of the four main characters from the Mouse Guard comics – Kenzie, Saxon and Lieam – with the fourth, Sadie, getting presented earlier on. The book uses them for its mechanical examples, but we'll be doing something different.

Audience participation time!

Audience participation time!

Let's build our Guardmouse, who I'll use for mechanical examples in future posts. I know you folks don't have a lot of the tools and context you need to work with, so let's keep it simple for now:

What rank is our Guardmouse? A rookie tenderpaw? Full-fledged guardmouse? Grizzled patrol guard? Experienced patrol leader? Commanding guard captain?

What are we best at? From the “Duties” section above, pick a task or two the Guard are expected to perform that our mouse is a real pro at. I'll take it from there.

Optional: What is our Wise? Name a thing we're Wise about. Owl-wise? Forests-wise? Forest Fires -wise? Blizzard-wise? Anything goes.

Add any other details you like, but the first two are enough to get us started.

Next time: Character creation!

Recruitment 1

Original SA post

Chapter 12: Recruitment

Mouse Guard posted:

Let this stone always stand for safety and prosperity.

Let it be your conviction, your pride, your home.

- Dedication recited to new Guardmice upon entering Lockhaven.

Yes, that's right, Chapter 12. Technically we're skipping about 90% of the book, but I'm reasonably confident that everyone reading this thread is an RPG veteran so we can detour from Luke Crane's lovingly crafted text structure and get to what people really want to see: making mice with swords.

There's another reason I'm skipping around like this, however. I made a big deal out of how important the Belief, Instinct and Goal (aka BIGs) are in the last post, and Chapter 3 deals with those in detail. You can't make BIGs without a character in hand, and you can't finish a character without BIGs, so for our purposes this will flow more naturally if we make the mechanical outlines of a character and then flesh it out in Chapter 3 with a Belief, Instinct and Goal.

As I mentioned upthread, Mouse Guard expressly forbids you from making characters in isolation. The whole patrol gets created at once, with every player answering the questions posed at each step before the group moves on. We could cheat and assume we're building a character for an existing patrol, but we need multiple mice for some of the mechanics examples anyway.

Right. Let's get started.

Concept

All we need to start is a rough sketch. The book suggests starting with age and specialty, which is what we've already done.

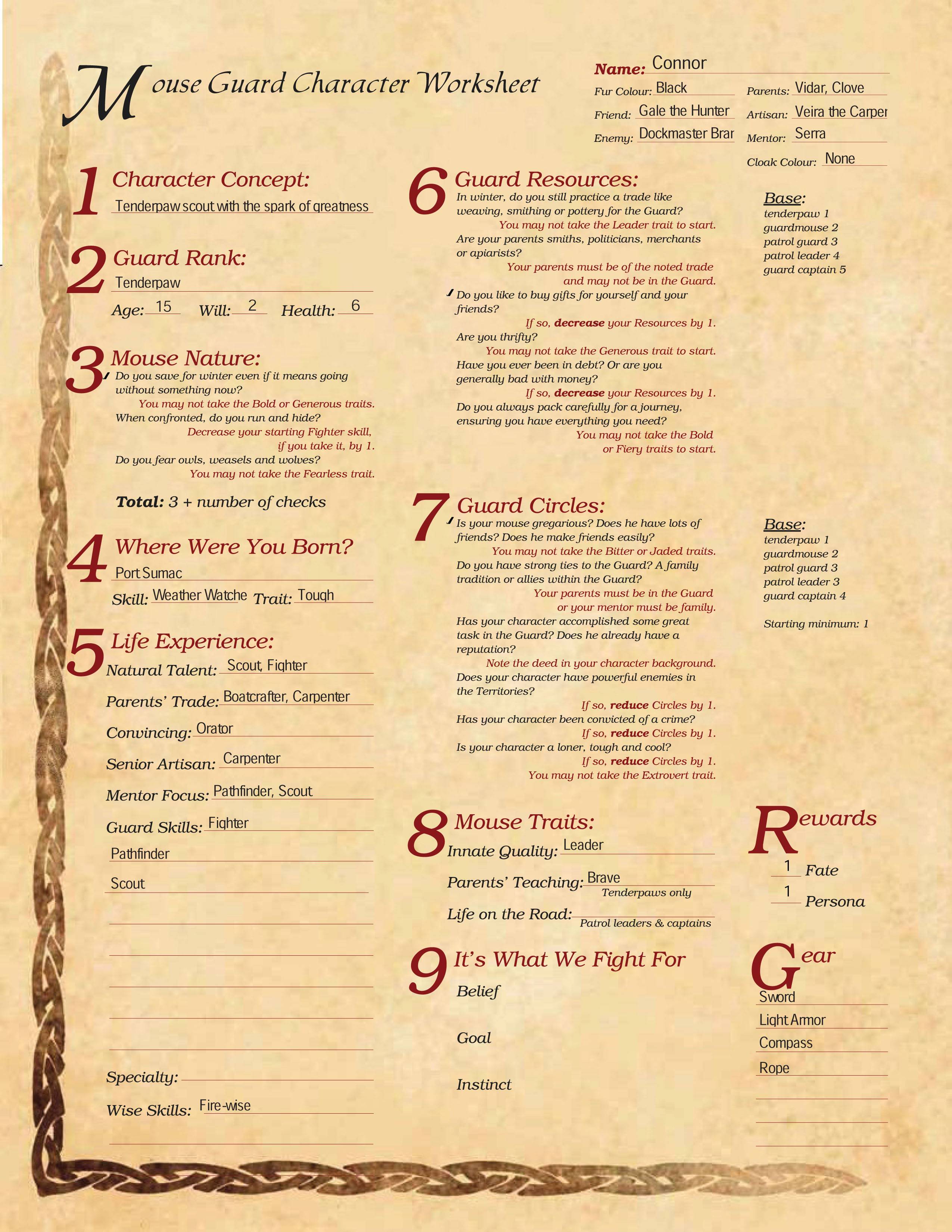

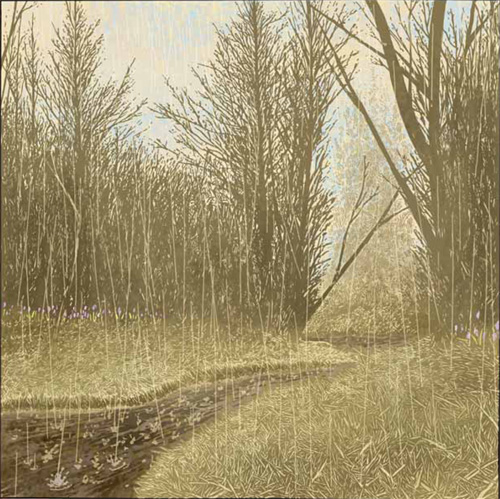

We'll be building a two-mouse patrol based on the concepts given by Dinictus and Dzurlord: a tenderpaw scout with some experience with fires, and a more experienced guardmouse known as a mediator and courier who knows the fastest route to anywhere.

Names come near the end, but for the sake of clarity I'm going to do it here. Let's call our tenderpaw Connor and our veteran guard Serra.

Guard Rank

This is the most mechanically-influential decision you make in character creation. The rank of a guardmouse determines – or at least sets the baseline for – a whole host of stats and skills.

The first thing a group needs to decide rank-wise is who's going to be the patrol leader. You always need one, and you can't have more than one outside of special circumstances like a pair of patrol leaders training a pair of tenderpaws, or the leaders of multiple destroyed patrols temporarily joining forces. Fortunately our patrol is simple: one patrol leader training up one tenderpaw.

Mouse Age and Ability

Based on our rank, we get our base stats from a simple table. Tenderpaw Connor is somewhere between 14 and 17 years old, and he starts with Will 2 and Health 6. Patrol Leader Serra is between 21 and 60, and she starts with Will 5, Health 4. We'll say Connor is 15, young even by the standards of the Guard, but promising enough to be assigned to Serra for one-on-one training. Serra's an old whitefur, closer to 60 than 50, still spry and quick-witted but knowing she needs to start looking for someone to pass on her knowledge to.

Mouse Nature

Remember Nature, that weird stat that determines how mousey / hawky / snapping-turtle-y you are? We're calculating it here. We haven't gotten to the full Nature mechanics yet, but here's a spoiler: Nature can be “tapped” to add a pile of extra dice to do things that your species' Nature implies, like hiding and foraging for Mouse Nature, but if it gets too high or too low it can temporarily take you out of the game.

Mice start with Nature 3 and answer a series of questions to determine their starting Nature.

-

If you save for winter even if it means going without now, +1 Nature and you can't take the traits Bold or Generous.

-

If you run and hide instead of standing your ground when confronted, +1 Nature and -1 to your starting Fighter skill if you have it.

- If you fear owls, weasels and wolves, +1 Nature and you can't take the Fearless trait.

How do our mice answer these questions?

Connor is young and impetuous, but he's barely out of the house at this point and I feel like the lessons of preparedness and frugality his parents taught him are still sticking around. He saves for winter even in spring. +1 Nature. Whitefur Serra is old enough to know the value of a stocked larder, but life on the trails has taught her to use what you have when you have it. No change.

We know Connor ends up with Fire-wise, and that suggests to me that Connor stands his ground. No change to Nature. Serra hasn't gotten to a ripe old age by fighting every weasel and toad that happens along, so she'll take the +1 Nature.

Connor has probably never seen an owl, weasel or wolf. He's not afraid of them – but he should be. No change to Nature. By contrast, Serra fought in the Winter War with the Darkheather weasels, and she has a healthy respect for their cunning and brutality. She's also seen what happens when the Scent Border fails and lets big predators into the Territories, so she knows well enough to fear them. +1 Nature.

At the end of all this, Connor is at Nature 4, Serra at Nature 5. This is pretty typical: you rarely see a guardmouse start play with Nature 6.

Where Were You Born?

The Territories .

Every mouse settlement imparts some skills and traits to its residents. Each entry has two or three skills and one or two traits, and you pick one of each. I don't have a preference here and want to be surprised, so I pick settlements at random.

Connor comes from Port Sumac, a port town in the eastern Territories close to the Scent Border. Mice from Port Sumac have access to the Boatcrafting and Weather Watcher skills and the Tough and Weather Sense traits. I'll pick Weather Watcher and Tough and put a check next to them on the character sheet.

Serra comes from Sprucetuck, the tree-city home of the Territories' best sciencemice. Sprucetuck mice can check the Scientist and Loremouse skills and the Inquisitive and Rational traits. I check Loremouse and Inquisitive. Don't worry

fans, I'll be revisiting the Scientist skill later.

fans, I'll be revisiting the Scientist skill later.

Life Experience

This a long section containing several sub-sections. It vaguely resembles a “lifepath” system ala Burning Wheel or Traveller, but without the mindboggling detail or the possibility of dying in a fusion core breach during character creation. The idea here is that we're going to answer questions about the past, each of which will put “checks” next to some skills. The starting rating of a skill is 1 + the number of times you checked it to a maximum of 6. At the end we'll have a fully developed skill list, and we'll know why each skill is at that rating, too.

CharOp Sidenote: Tests in Mouse Guard are hard. Obstacles are commonly in the 2 or 3 range, which means you need at least 2 or 3 dice in your pool to come up 4, 5, or 6. Even with a skill maxed out at 6, odds are you fail a lot. This is by design. It forces patrols to coordinate and find creative solutions to their problems with the Help rules, which we'll get to later. That said, it's best practices to have at least one skill at 4 or 5, preferably a second at 4, then diversify heavily if you can so you can be as Helpful as possible to your patrol.

Pick an area in which you're naturally talented.

This is the easy one. Our Tenderpaw can choose two skills from the big list, our patrol leader can choose one.

Connor checks Scout and Fighter. His sharp eye is what put him with Serra in the first place, and he's a scrappy little guy.

Serra checks Pathfinder. This is what she does after all.

What was your parents' trade?

Again, tenderpaw chooses two, patrol leader chooses one. This is a more restricted skill list, consisting of trade skills like Apiarist (beeees), Harvester and Stonemason.

Our tenderpaw can stack those two checks, but for diversity's sake we'll split them up. One more check on Boatcrafter and one to open Carpenter from mom and dad respectively.

Our patrol leader only gets one choice, and it goes straight into Cartographer. Mom and dad just loved maps.

How do you convince people that you're right or to do what you need?

There's only three choices here: Deceiver, Orator, or Persuader, the social skills of Mouse Guard. Deceiver includes intimidation and platitudes so it's not quite as Wormtongue as it sounds, but it's got a social stigma attached. This time our patrol leader chooses two and our tenderpaw chooses one.

Connor checks Orator. I'm starting to get a feel for this character, and it sounds like he's the ~*~ inspiring young hero ~*~ type.

Serra checks Persuader twice. We know she's conflict-averse, and this fits her style.

With whom did you apprentice for the Guard? What was that mouse's trade?

More trade skills, this time relating to meeting the material needs of the Guard. Everyone gets one check here, and your choice is noted for when you create your Senior Artisan.

Connor's Boatcrafter skill isn't much use to the landlocked artisans of Lockhaven, so he'll put another check on Carpenter. Thanks, dad!

Serra puts another check on Cartographer. The Guard is constantly updating its maps to account for changes in the forest terrain.

What did your mentor stress in training?

Tenderpaws get a few seasons of hands-on field training under a patrol leader before they get promoted to guardmouse. The skills their mentor emphasizes – or, in the case of patrol leaders, are currently emphasizing to their charges – is a big deal for a guardmouse. This time, both characters get two checks to spend.

Based on the character concepts, we know Serra is going to emphasize trailblazing and similar skills for her trainee, so we'll give Connor checks on Pathfinder and Scout.

Serra's own mentor, way back in the day, probably set her on the path she's on now. There were certainly other lessons learned, but Pathfinder is what she's passing on to Connor as well, so we'll emphasize it with two checks.

What kind of experience do you have in the Guard?

Skill bonanza time. This is where your choice of Guard Rank starts to tell. Our Tenderpaw can spend three checks on the list of Guard-related skills, while our experienced patrol leader has a whopping nine to burn.

Connor throws a point each into Scout, Pathfinder and Fighter. He's got some basic competency in his scout / courier duties now.

Serra has all the checks . She drops two each in Persuader and Survivalist, three in Scout and one more in Pathfinder, making her a serious outdoorsmouse, and one check in Instructor so she can pass on what she knows.

What's Your Specialty?

Last one! Our tenderpaw is too green to have a specialty, but patrol leader Serra gets one more check to spend on the Guard skill list. Specialties have to be unique within a patrol, but that's not an issue for us. She'll throw one more check on Pathfinder because damnit, we're going to be good at this.

Now all that's left for skills is to tally it up. Here's where we stand:

Connor, Tenderpaw

Will 2

Health 6

Nature 4

Skills

Boatcrafting 3

Carpenter 3

Fighter 3

Orator 2

Pathfinder 3

Scout 4

Weather Watcher 2

Traits

Tough (1)

Serra, Patrol Leader

Will 5

Health 4

Nature 5

Skills

Cartographer 3

Instructor 2

Loremouse 2

Pathfinder 6

Persuader 5

Scout 4

Survivalist 3

Traits

Inquisitive (1)

This section ran longer than I'd anticipated because I like words, so I'm going to finish up the rest of character creation in a follow-up post. It also occurs to me that my being so goddamned

about this may make it seem more time-consuming or complicated than it actually is, so I'm going to use the concept Dereku posted and see how long it takes to make a mouse when I'm not writing commentary. Yes, yes, I'm breaking the first law of character creation, but It should at least be an interesting experiment.

about this may make it seem more time-consuming or complicated than it actually is, so I'm going to use the concept Dereku posted and see how long it takes to make a mouse when I'm not writing commentary. Yes, yes, I'm breaking the first law of character creation, but It should at least be an interesting experiment.

Next time: Finishing up character creation, including Wises, Traits, and people who want us to suffer.

Recruitment 2

Original SA post

Chapter 12: Recruitment, Part II

Time to finish off these mice -or at least as close as we're going to get until we fill in the all-important Beliefs, Instincts and Goals in the next post.

We still have one more sub-section of “Life Experience” to get to, but I love Wises to death and am mad with power so I'm going to elevate it to its own section.

What are you particularly knowledgeable about?

Wises are skills, but they're strange skills. They represent a body of specialized knowledge, often about esoteric or idiosyncratic subjects. The 34 main skills in Mouse Guard give you a pretty good idea of what life in the Territories is like: when Apiarist and Glazier are considered major skills in the setting, life's probably on the quiet side for mice who aren't in the Guard. But the Guard are constantly living, as the saying goes, in interesting times, and they pick up some unusual skills as a result.

From a more practical character creation perspective, Wises are what you buy when you want to spice up a character's skill set or highlight something important in their background. If your concept includes surviving a vicious storm, for example, taking Storm-wise or Foul Weather-wise can bring that into play in a concrete manner. Wises also break the skill rules in some interesting ways, but that gets its own coverage elsewhere. For now we're focusing on what they can do for the character concept.

As with other skills, your Guard Rank determines how many checks you get to throw at Wises. Our tenderpaw gets one, while our patrol leader gets four. There's a big list of Wises to choose from, or you can make up your own for a town, an animal, a group or specific person, or just about anything else you want. Ours will stay pretty traditional, but you can get crazy with Wises if you want.

Connor's Wise was dictated in his character concept: Fire-wise. Man do I love that one.

Serra's Wises are also hinted at in the concept. She's all about getting from one place to another quickly, so we'll spend two of her checks on Shortcut-wise and another on Trail-wise. The final point goes into Predator-wise, because going off the beaten track that much (and surviving) is bound to teach you a few things about how not to get eaten.

Guard Resources

Now we find our pay grade. Tenderpaws start with Resources 1, while our patrol leader starts with Resources 4. From there we answer more questions to find out what our starting Resources are.

-

If you practice a trade in winter for the Guard, +1 Resources. Downside is that you need to actually have a trade, and this may limit what you can do in the Winter Session downtime.

-

If your parents practice a lucrative trade like smithing, apiary or politics, you are a privileged oppressor of the people and get +1 Resources.

-

If you like to buy gifts for people, -1 Resources but you're not Mouse Scrooge. If you're thrifty, +1 Resources and you can't take the Generous trait.

-

If you've ever been in debt or spend all your money on ale and whores, -1 Resources.

- If you always pack carefully for a journey, +1 Resources but you can't take the Bold or Fiery traits.

Connor hasn't settled in to a trade for the Guard and his parents aren't particularly wealthy. He's a kid getting his first paycheck, so I can't see him being especially thrifty either. Fortunately he's too young to have a history of profligate spending, but he's also not the type to pack carefully for a journey either – he's too green to even know what to take half the time. All told, Connor is sitting at Resources 0. We can increase this in-game, but it'll take some help.

Serra is a different story. She practices Cartography for the Guard during the Winter, updating the old maps and working with the Loremice. She's a solitary creature who's spent most of her life in the Guard and outlived her friends, so her pay just piles up, and she's rarely in a settlement long enough to spend it. Besides, ale and whores are for younger mice. Finally, this old veteran definitely packs carefully for every journey. Serra has a solid Resources 7, and Connor has a sugar mama.

Guard Circles

Ah, Circles, the “Who you know” stat for creating NPCs out of whole cloth. As with Resources, tenderpaws start with Circles 1 and patrol leaders with Circles 3. There are even more questions here, but there's quite a few of them and it makes me vaguely uncomfortable reprinting large portions of the book verbatim, so I'm going to summarize the results.

Actually, I'm going to make one exception because it amuses me:

Mouse Guard posted:

Is your character a loner, tough and cool?

If so, reduce Circles by 1. You may not take the Extrovert trait.

Connor's an outgoing sort who makes friends easily, but he doesn't have any ties to the Guard beyond simple enlistment and still has a lot to prove. He starts with Circles 2.

Serra is almost the exact opposite. She's a gruff old gal with a long history in the Guard, including some decorated actions in the Winter War. She's made an enemy of an especially vicious weasel Tunnel Lord after her ambush cost him his war party and an eye, and to her misfortune he survived the War. She'll start with Circles 4.

Mouse Traits

Traits make you a special snowflake. If you have a trait, it's probably how people describe you. You're not just Clever, you're The Nimble One, and so on. Traits have three ranks, purchasable with checks or earned in-game, which give you bonus dice or let you re-roll failed dice when the trait would be applicable. Our guardmice already have some traits: Connor has Tough (1) and Serra has Inquisitive (1). Now we'll select more from some Lifepath-esque lists.

Choose a quality you were born with.

Every mouse gets one free check to spend on a trait. Connor's concept suggests he has something of the born leader in him, so we'll give him Leader straight-up. Serra's intellect is something we've touch on but haven't brought in mechanically, so she'll get Quick-Witted.

Choose something you learned or inherited from your parents.

Only tenderpaws get this one, and the list is shorter than others, but it's got some good choices on it. We'll say Connor gets “Brave” from his boatwright mother.

Life on the Road

Patrol leaders and guard captains get to pick a trait from a more adventure- and hardship-oriented trait list. Serra's age is an important part of the character, so she'll get Oldfur.

Normally we'd choose a name here, but we've done that already, so it's on to –

Fur Color

Cosmetic details, woo. Seriously though, for the sake of color coordination we'll say Connor is a black-coat to contrast Serra's white and call it good.

Parents

We know a fair bit about the parents of our characters. Now we name them and put them on the character sheet proper.

Connor's folks are Vidar and Clove. Serra's parents should probably be deceased by now, but for the sake of completion we'll go with Faolan and Kearra.

Senior Artisan

This is the one our mice apprenticed under in their first seasons in the Guard. For Connor that's Veira the Carpenter; for Serra it's Thurstan the Cartographer.

Mentor

Our first teacher in the Guard. Tenderpaws have to pick the patrol leader PC in their group, so that's easy enough. Serra's mentor who taught her pathfinding and the hidden ways of the Territories is Captain Gurney. The ancient mouse is now one of Matriarch Gwendolyn's advisors, but he never leaves Lockhaven.

Friend

Now we need a friend or ally, a BFF who will come through for us no matter what. They need a name, a profession or specialty, a place of residence, and how they relate to the character.

Connor's Friend is Gale, a tomboy friend from childhood who moved from Port Sumac to the remote outpost of Pebblebrook on the weasel-haunted western border near Darkheather. Gale couldn't abide the rigid hierarchy of the Guard, but she has enough woodcraft to make herself useful to the Pebblebrook mice, and she's the best shot with a sling in the region. Connor and Gale were inseparable as kids and they've kept in touch by letter since they parted ways.

Serra's Friend is Sloan, a sciencemouse who's the son of an old patrol member, now deceased. Sloan thinks of Serra as a beloved aunt, and the two of them have spent a lot of time in the wilderness working on Sloan's obscure projects. Sloan's home base is in Sprucetuck, but he spends a lot of time on the road collecting specimens and trying to figure out things like why his latest mixture is attracting wasps instead of deflecting them.

Enemy

Not every mouse in the Guard has someone who's out to get them, but every player-character sure does. Like Friends, your Enemy needs a name, an occupation or specialty, a place of residence, and a reason why they hate your guts. Enemies should be mice, because that makes them harder to get rid of. You can always kill a weasel or a hawk with enough effort, but the Mayor of Shaleburrow is going to be harder to deal with.

Connor's enemy goes all the way back to Fire-wise. Before he joined the Guard, Connor rescued some mice trapped by a wildfire, but was forced to leave behind the grievously injured wife of Brand, the dockmaster of Port Sumac. The man holds Connor a grudge, believing that the boy chose to leave his wife behind as revenge for some slight against Connor's family.

Serra's enemy is Noelan, the son of a merchant family out of Copperwood. Early in her career, Serra arbitrated a dispute between two merchants. Her decision was made with the best of intentions, but it had unintended consequences which led to the slow, painful decline of Noelan's family. It's been decades since, and Noelan has rebuilt his family fortune, ironically, by supplying the Guard with metal for their voracious forges. Word is he's looking to settle the score before old Serra can retire.

Cloak Color

The color of a guardmouse's cloak represent some quality their mentor saw in them and considered worth displaying to the world. Tenderpaws haven't been formally inducted into the Guard yet, so Connor doesn't get a colored cloak. He'll earn it in play, and Serra's player will choose its color when the time comes. Serra's cloak is a dark blue-grey, which Gurney felt represented hidden depths in his student.

Gear

Technically we do Beliefs, Instincts and Goals before this, but those are being saved for next time. As mentioned earlier, you can carry whatever gear fits in the space alloted to write it down, plus a weapon; there's no resource points or gear lists to comb over. Most guardmice travel light.

Connor's weapon is the sword. He routinely carries some Light Armor, a little compass, and some rope. You can never have too much rope.

Serra's weapon is the bow. She carries maps and map-making tools, spare rations and water, and an assortment of small tools like a carving knife and tinderbox to use with the Survivalist skill.

Summary

We made it! Here's what our guardmice look like now on the form-fillable character worksheets:

Jesus. I wrote 4000 words about this, and it's contained in two pages with giant fonts. Welp.

All that's left for these characters is their Beliefs, Instincts and Goals, which are the subject of Chapter 4: What We Fight For.

Next Time: The three most important things on the character sheet, plus the Mouse Guard reward cycle.

Sidenote: Character Creation Speed-Run Challenge

As promised, I did a speedrun of character creation from scratch using the book, paper and pen and timed it. From concept (inspired by dereku and merged into a tenderpaw version of Lemon Curdistan's idea) to gear, it took 14 minutes 32 seconds. Granted, I can crank these out pretty quickly and character creation always goes at the rate of the slowest player in any given section, but that's not bad.

I've actually grown rather fond of this character, so our two-mouse patrol may be joined by a weasel-fightin' spearmouse when it comes time to go over the Conflict system. Thanks, dereku and Lemon Curdistan!

It's What We Fight For

Original SA post

Chapter 4: It's What We Fight For

At eight pages long, Chapter 4 is tied with the Introduction for shortest chapter in the book. It's also arguably the most important, so it's going to get a disproportionate

to pagecount ratio. Chapter 4 is about Beliefs, Instincts and Goals (BIGs) and the reward cycle of Mouse Guard. We'll be finishing up our sample characters here, too. I'm also going to make some comparisons to Burning Wheel for readers who've played that game but haven't gotten around to Mouse Guard yet, because there's some interesting differences between the way BW and MG handle what at first glance look like the same mechanics.

to pagecount ratio. Chapter 4 is about Beliefs, Instincts and Goals (BIGs) and the reward cycle of Mouse Guard. We'll be finishing up our sample characters here, too. I'm also going to make some comparisons to Burning Wheel for readers who've played that game but haven't gotten around to Mouse Guard yet, because there's some interesting differences between the way BW and MG handle what at first glance look like the same mechanics.

Beliefs

First up are Beliefs. I'm going to quote from the book a fair amount this time, because the way these ideas are communicated is important and the author does a better job of it than I can.

Mouse Guard posted:

A Belief is a code or ethical stance. It's a snapshot view of how your character thinks. Sometimes you'll act in accordance with your Belief, sometimes you'll act against it.

Beliefs need to be clear, powerful statements with a potential for conflict. “The Guard is good” is a bad Belief, but “The mice of the Territories must know that the Guard is good and must be supported” is pretty hot. Beliefs are also recommended as a guide for decision-making in play. If you're not sure what you should be doing right this minute, look at your Belief and figure out what it compels you to do.

This section goes on to tell us that when we write our character's Belief we should share it with the table because – and this is the important part – Beliefs tell the other players what you're interested in and want to explore in the game. Beliefs can and will change over time, but a character's current Belief is like a spotlight on what you're interested in for the game.

RPG Theory Tangent

Beliefs, along with the Goals and Instincts we'll be looking at next, are known in theory circles as “flags.” A flag is something on your character which signals to other players and the GM that you want to address and be challenged by certain things in the game. Some games like Mouse Guard and Burning Wheel are explicit about their flags, but they're present even in games like D&D: your wizard preparing a rack of utility spells like Tenser's Floating Disc and Animate Rope is a silent signal to the rest of the table that you want obstacles to overcome with your personal cleverness and utility. If you wanted to blow shit up you'd have prepped eight flavors of Fireball and had done with it. Beliefs work the same way: someone who writes the Belief “A guardmouse thinks with her head and acts with her heart” wants situations in which she can be clever and compassionate, and possibly ones in which cleverness and compassion are set at odds with one another.

[/endtangent]

The next couple of pages – that is, a quarter of the chapter – go over this idea from different angles. It ends with a section for the GM which I'm going to put up verbatim. For context, Sadie, Saxon and Kenzie are three main characters from the comics. Sadie's Belief is the “think with your head, act with your heart” one I mentioned above.

Mouse Guard posted:

It's your job to challenge that Belief in the course of play. You present the player with situations that say, “You believe that? Cool. How about now? Do you still believe that if I push you?”

Put the character in situations where the reputation of the Guard is at stake: missions with a high public profile, for example.

Sadie's player has to make a difficult choice between what her heart wants and her head tells her. That is precisely the point of a Belief. It makes the situations in the game more gripping.

For even deeper, richer play, tie in other characters.

Saxon and Kenzie are the perfect example of this dynamic. Saxon's Belief is very direct: “The best solution is always found at the point of my sword.” Kenzie's Belief is more philosophical: “It's not what you fight, but what you fight for.”

When they encounter a problem, they both have a different idea of what should be done. This leads to tension, discussions, arguments and sometimes even fights! But it makes the characters rich and engaging.

“All right,” you say, “enough with the ~*~ roleplaying theory ~*~, what do you do with Beliefs?” We're getting to that. Beliefs tie into the reward mechanics, so playing them has a tangible, mechanical benefit which we'll see at the end of the chapter. For now though, let's revisit our sample characters.

A Burning Wheel Aside : Those of you who've played Burning Wheel may be scratching your heads right now, because Beliefs in Mouse Guard don't look like Beliefs in Burning Wheel. They're the same concept, they feed into similar rewards, but the wording is all wrong. A Burning Wheel Belief starts out with a philosophical statement like a Mouse Guard Belief, but it requires an action or a goal at the end which allows you to resolve the Belief and get the big rewards. The key word here is “goal.” Burning Wheel Beliefs were split in half for Mouse Guard, with the philosophical statement keeping the label “Belief” and the resolution-achieving action becoming the “Goal.”

Example: Building Beliefs

Our sample two-mouse patrol isn't quite done yet. Tenderpaw Connor and patrol leader Serra need Beliefs before they're ready for play.

I have a decent feel for Connor at this point. He's young, brave, outspoken, a natural leader. In short, he is every young adult fantasy protagonist ever. It's easy to fall into the trap of looking at this character and saying, “I need to write a Belief that epitomizes these qualities” and wind up with something that just restates your Traits. It's important to remember that Beliefs are out-of-character flags of player priority , not the sum total of the character's heart and soul. If I were playing Connor, I'd like to see what happens when he tries to assert himself in situations he's not equipped to handle or bucks authority he doesn't agree with. I'll write a Belief with that in mind:

The Guard will not survive without new voices and new directions.

As a setting side-note, this ties in to the Winter War and the recent Midnight debacle, two major upheavals in the order of the Territories which would have occurred in Connor's formative years. The Guard was nearly destroyed twice in the span of four years, and there are stirrings of anti-Guard sentiment among the commonfolk which have put the organization in jeopardy. This might be a Belief that sticks around on the character for a long time, or change its form radically if I hit on an appealing “new direction” for the Guard in play and decide to champion it.

Serra's a bit harder to pin down. If I were playing her I'd want to avoid the “stodgy traditionalist” thing that happens so often when someone plays a character over 35. After all, Serra grew up among scientists, and she's Inquisitive and Quick-Witted. I like the idea that Connor's earnest, youthful passion inspires her, and that she is both a literal and metaphorical pathfinder for him and others. Based on that, I come up with:

The duty of the old and the wise is to prevent past mistakes from being repeated.

This is a more philosophical Belief, similar to Kenzie's above. At some point I'd also want a Belief about the weasel Tunnel Lord who's out to get her, but this seems like a good one to start a campaign with.

As a GM I'd want to look at these Beliefs, first separately and then together, and find ways to challenge them in play. A major settlement on the Darkheather border making diplomatic overtures toward the weasels, perhaps? When the Guard inevitably finds out and responds, Connor has to figure out whether considering the possibility of peace with their ancient enemies is worth helping the settlement and potentially bringing a viper into their midst, or following the Matriarch's orders to assure peace now . Serra, who saw the horrors of the Winter War first-hand, has to decide how to counsel both the settlement and the Guard. Can they achieve a lasting peace through diplomacy, or does Darkheather understand only strength?

Goals

Your Goal is what you're going to accomplish this session. A Goal has to contain:

-

A statement about your character (e.g. “I will,” “I will not,”)

-

An action (“find,” “stop,” “protect”)

-

A target (“Connor,” “the weasels,” “the settlement”)

- Optionally but preferably, a condition (“quickly,” “before the storm arrives”)

Goals are created in response to the GM describing the Mission of the session, or, less typically, in response to the players setting the patrol's goal for themselves, something you'd normally see only when the patrol is acting outside the chain of command. Goals should be related to the Mission, but they don't necessarily have to be about the Mission. Valid targets include other members of the patrol, the patrol as a whole, groups or specific characters, and so on. For example, Serra's player would be a-okay with taking a Goal like “I will keep Connor out of trouble on this mission.”

Finally, Goals have to be achievable in a session, direct, and can't be something you can do right away. “Bring peace to the Territories” and “Bake a pie” are both invalid Goals, but for different reasons: one because it's more than a session long and has no direct route, the other because it's too easy and could be done right away. Besides, there's a mechanical incentive to achieving your Goals in a single session: delicious reward points, which we'll see shortly.

Like Beliefs, Goals are signs to the GM, but writ large. If a Belief is a signpost listing the mileage to cities on your route, a Goal is a huge flashing neon sign advertising something at the very next stop. GMs rely heavily on Goals to fill out the content for their sessions. Ironically (some would say perversely ), the fact that Goals are written at the table after the Mission is handed down gives the GM no prep time for Goals whatsoever. Let's just say Mouse Guard makes you good at improv GMing.

Goals are a hell of a lot easier to write than Beliefs, which is good because they'll change every session, possibly twice a session if your group runs long sessions (6+ hours). I'll skip the example here and end this section with an excerpt from “Playing Goals” which ought to be burned into the inner eyelids of everyone who plays a roleplaying game. Emphasis will be mine.

Mouse Guard posted:

In play, your GM is going to use your Goal as a guideline for what you're interested in playing during this session. Once he knows what you want to accomplish, he's going to throw obstacles in your way. A hero is defined not by what shining gem he ultimately captures, but by what obstacles he overcomes to reach his Goal.

So, when you see a hurdle in your path, run toward it. Don't avoid it. Those obstacles are the moments when you get to define yourself as a hero. Succeed or fail, it doesn't matter. You must try. And if you keep trying, you'll succeed. The only thing that can stop a guardmouse is death – and even that rarely works!

Instincts

Your Instinct is a physical action you take automatically, something you always do, never do, or do in response to a specific stimulus. It's a part of who you are, a trademark action or reaction which gets you rewarded if you perform it. Some Instincts are a single physical action, like “Always draw my sword at the first sign of trouble.” Others are moments of snap decision-making, like “Never delay when on a mission.” Whatever they are, they have to be something you can do at a moment's notice, or can be assumed to always or never do all the time.

Instincts are another flag, just as direct as a Goal: someone with an Instinct like “Never delay when on a mission” wants situations to come up which would make it tempting to delay. If their mission is to reinforce the Scent Border before predators find the breach, will they take a detour to rescue a friend or hunt for an old enemy?

Beliefs and Goals can be tricky to write, but Instincts are dead easy. Think of something you want your character to do all the time , then attach an Always / Never / If-Then to it. Let's do a couple of quick ones for our example patrol.

Connor hasn't had much time to develop guardmouse Instincts yet, but we know he throws himself into harm's way to protect others. That suggests an Instinct like “Always come to the aid of mice in danger.”

Serra has had years of experience in the wild and at the negotiating table. I want an Instinct for her that can cover both equally well. Seeing her Inquisitive trrait provides the inspiration I need for the Instinct “Never commit to a course of action without knowing all the facts.”

There's not much more to Instincts than that, so it's almost time to wrap this chapter up with a look at Rewards. But first, another brief aside.

A Burning Wheel Aside: Burning Wheel players are probably not too happy with those Instincts. They'd work, but they're iffy. A BW Instinct should ideally be even more action-oriented or preparatory, and what's this nonsense about getting rewarded for performing the Instinct anyway? The classic way to describe a Burning Wheel Instinct is as an action-oriented macro, like “Always carry a knife concealed on my person.” If the Instinct gets you in trouble, like getting frisked by the palace guard and stating that yes, you're still hiding a knife on you, then you get rewarded. Mouse Guard Instincts are different. They're less about covering yourself or getting into trouble as they are about adding flavor to the character and putting up another flag for the GM.

Summary

Taken together, Beliefs, Instincts and Goals are what really drive Mouse Guard. Yes, the GM is responsible for creating missions and setting the world in motion around the PCs, but that's a more reactive role than you'd think. Missions should be designed with the Beliefs and Instincts of the patrol in mind, and Goals make GMs put on their improv hats from the word “go,” adding new elements to the mission to accommodate Goals or finding ways to address them with the content they've already prepared. In a very real sense, a group's experience with Mouse Guard is dependent largely on the strength of their BIGs and how effectively the GM addresses them.

Rewards

That was a lot of words about what may seem like very fluffy concepts. But aside from flags being hugely important for roleplaying games in general, the reason BIGs are – I'm sorry – a big deal is that they reward you with Fate Points and Persona Points.

Acting on a Belief, working toward (but not accomplishing) your Goal, or playing your Instinct are worth a Fate Point at the end of the session. You can spend to open-end (or, for you Star Wars D6 players, “explode”) any dice that come up 6s on a roll, potentially allowing you to get more successes than you have dice. Because Mouse Guard tests often have brutally hard obstacle numbers, Fate Points are incredibly important and you want lots of them.

Acting against your Belief in a compelling way – making a decision that runs counter to it and acting on that decision – or accomplishing a Goal gets you Persona Points, which straight-up add dice to a roll. Spending a Persona Point also lets you channel your Nature stat, adding a pile of dice to a roll but potentially costing you points of Nature if you fail or if the act itself runs counter to Mouse Nature.

As with Fate Points, Persona Points are vital due to the difficulty of the challenges guardmice face on a regular basis. There's also an obvious synergy between the two rewards: more dice to roll means more potential exploding sixes.

There's also a few points of Persona waiting to be claimed at the end of a session. The “MVP” point goes to whoever made the roll most crucial to the success of the mission. The “Workhorse” point goes to whoever had a bunch of useful skills, made necessary but unglamorous rolls, and generally slaved away outside the spotlight. Finally there's “Embodiment” points, which are given out for excellent characterization and generally roleplaying beyond the call of duty.

This isn't the entire reward economy in Mouse Guard. Fate and Persona points keep you going during a mission and reward you for playing your BIGs, but missions aren't everything. The space between missions is at least as important, and there's a whole other reward economy that goes in there, which we'll touch on in the next chapter. Chapter 5 is a big one, by the way, so I'm going to split it up into two posts.

Next Time: Chapter 5, “Missions,” Part 1. The structure of the game, the GM's Turn, and beating the crap out of PCs.

The Mission

Original SA post

Chapter 5: The Mission

Time to take a look at how you actually play this game. Sessions of Mouse Guard have a structure to them which, so far as I'm aware, is unique in RPGs. Chapter 5 describes this structure and gives you an idea of how to run the game. We'll also be revisiting our sample patrol, who will show up in quote-block example text. This is a decently long chapter, but I've decided against breaking it apart as I said I would last time because it works better as a single post.

Forming the Patrol

The first few pages of Chapter 5 are essentially a “care and feeding of a roleplaying group” guide: assembling a group of players, figuring out who should GM, setting a date and time to play, printing out character sheets and rules summaries, and so on. It's not much use to experienced players, but the text is written for complete newbies so it's nice to see this sort of thing included.

Advice for a group's first session follows. It recommends that new players pick sample characters and do an intro mission instead of diving into the character creation options, or at very least customize one of the Template Characters from later in the book. We also get another stern warning to do character generation as a group, with everyone either making characters or choosing templates together. There's a lot of good, sensible newbie advice here that you just don't see in most books. Things like “if you're adding a new character to an established patrol, making other people wait for you to make a character is rude, so just grab a template and go.” We're also given an easy in for adding new players mid-game: the Matriarch sent more help as it became available. Having this in-setting excuse for a flexible party is a godsend if your group isn't particularly stable from week to week, like gamers with families or after-school groups.

Prologue and Seasons

There's a bit of administrative work before a session starts. The patrol's Beliefs, Instincts and Relationships get read out and updated if necessary, and the GM adds them to a quick-reference sheet. Next is a “prologue” where one player gives a summary of the previous session to refresh memories and get players who were absent the last time caught up; whoever delivers the prologue gets to recover some of their lost resources.

Finally, the Season for the session is determined. Seasons are a big deal: the forest tries to kill you in different ways in spring than it does in fall, and the Guard's duties change by the season. Spring is the traditional starting season for a new patrol, and Winter has special rules which prohibit new games from starting in that season. Mouse Guard campaigns are designed to last for one or two full cycles of Seasons, so you can calibrate the length of your campaign by deciding how many sessions it takes for a season to elapse.

The Patrol posted:

Connor and Serra's patrol is ready for duty in Spring. This is a dangerous time in the Territories: the weather is unpredictable, flash floods and lightning storms are common, and predators hungry from a long winter are on the prowl.

Meeting the Matriarch

The session proper begins with a brief scene between the patrol leader and the Mouse Guard Matriarch, Gwendolyn, in which she hands down the mission to the PCs. The book admits that Gwendolyn is basically the GM's avatar, but that she's also a character in her own right: wise and compassionate, but fiercely devoted to the ideals of the Guard and its survival. You're encouraged to get in to the role instead of simply handing down a mission summary from on high and to develop the relationships between the Matriarch and her patrol leaders and captains. For the “new roleplayer” audience the book is aimed at, the scene between Gwendolyn and the patrol leader is the first actual roleplaying they'll do, and the text emphasizes its importance.

Mission information from Gwendolyn tends to be short and to the point: go here, do this, within this time frame. Gwendolyn is up-front with what she knows and expects, but like a briefing from a Mr. Johnson you rarely get the full story about the mission until you arrive on site.

Now the PCs write their Goals. As mentioned, these should relate to the Mission but aren't necessarily about it. This is the point at which the GM starts to scramble. It's my experience that players rarely latch on to the things in Missions you think they will, so the GM uses this time to think about how their pregenerated content fits with the Goals being written and whether they need to start coming up with new material on the fly. Hint: you will.

The Patrol posted:

Word has reached the Matriarch that the settlement of Pebblebrook near the western border has opened negotiations with the Darkheather weasels. Gwendolyn believes the safety of the Territories is at stake, but the Guard has no authority over Pebblebrook. The Matriarch dispatches Serra and Connor to the settlement to end its negotiations with Darkheather by any means necessary. If they can find out what the weasels' game is in all this, so much the better – Gwendolyn refuses to consider the possibility that the weasels could deal in good faith.

Connor writes the Goal: I will ensure that the Pebblebrook mice are safe from the weasels of Darkheather. It's a Goal that doesn't give him a stance in either direction on what Gwendolyn has asked him them to do – after all, maybe the best thing for Pebblebrook is to make peace with Darkheather. It does, however, require a lasting result. No half-assed solutions are acceptable here.

Serra writes the Goal: I will convince the people of Pebblebrook that the weasels cannot be trusted before they sign the treaty. That's a Goal with a course in mind. Serra's player has put out a clear flag saying “Get ready for social conflicts.”

The Mission

This is the meat of the chapter: how to design a Mission, and the framework that exists around it.