Deities & Demigods 1E by Jerik

A Brief History of the Planes

Original SA post Deities & Demigods 1EPart 1: A Brief History of the Planes

Hey, I've been lurking here for a couple weeks, but decided it was time to make an account and contribute, and after some thought I figured something I could tackle was my favorite D&D setting: Planescape. I know this setting very well (well... I knew it; honestly it's been long enough since I've done anything with it I've probably forgotten a lot)—I have all the Planescape supplements; I've run several campaigns in the setting; and I was one of the contributors to the semi-official-but-not-really 3E Planescape conversion on planewalker.com. (Though I wasn't one of the editors, and I'm not in favor of all the decisions they made.) When and if Wizards of the Coast ever opens up Planescape to the DM's Guild, I'm going to jump right in with my own Planescape books and adventures. But as much as I love the setting, I don't think it's perfect by any means, and I think it's worth discussing in detail.

(This decision has nothing to do with Mors Rattus's review of the clearly heavily Planescape-inspired Sig. I had already begun writing these reviews well before those started—I wanted to be a few posts ahead and have several parts of this review written before I actually posted the first one—, so the timing is entirely coincidental. In fact, the entirety of this first post was completely written before the first Sig post dropped, except of course for this paragraph.)

Okay, I checked out the archives, and I see that the first few Planescape products were previously covered by SirPhoebos (and one later adventure has a partial review by DAD LOST MY IPOD). But most of them weren't, and even those that were I have lots to say about that isn't in SirPhoebos's (or DAD LOST MY IPOD's) reviews, so I think it'll still be worthwhile for me to write up my own take on them.

So let's get started.

Or actually, let's not, quite yet. I was going to start with the original Planescape Campaign Setting boxed set, but on second thought I think I'll go back a little earlier. Planescape came out during the time of the second edition of Dungeons & Dragons (or "Advanced Dungeons & Dragons", as it was then called to contrast it with "Basic Dungeons & Dragons"), but it had roots in first edition. The most obvious inspiration is the first-edition Manual of the Planes. And so I was going to start with that... but then I figured, what the hey, let's go back even earlier.

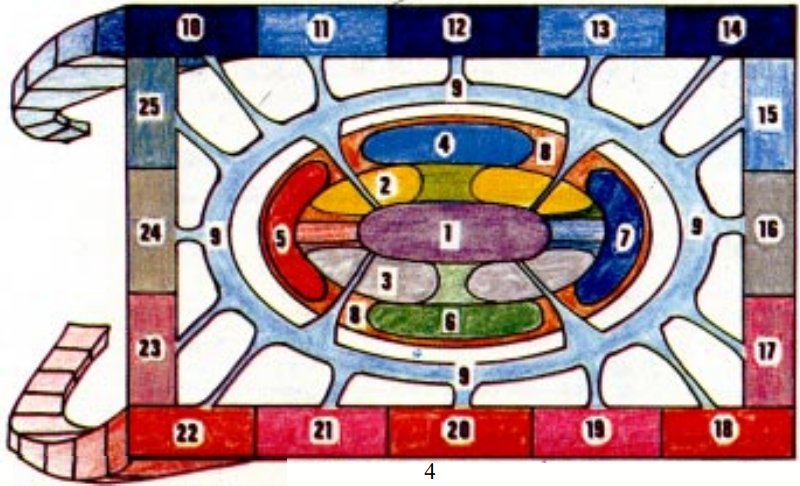

The Manual of the Planes was the first book to really describe the planes in detail—and its descriptions were mostly followed in Planescape, and in later presentations of the D&D planes. But it wasn't the first book to define the D&D cosmology. The existence of other planes had been hinted at as early as the original Dungeons & Dragons boxed set, which included the spell "Contact Higher Plane"—or arguably even earlier in D&D's predecessor Chainmail, which included elementals that had to be "conjured up by a Wizard", though it didn't specify where they were "conjured up" from. (Incidentally, is it just me, or is "conjured up" kind of a weird phrasing? "I'ma gonna conjure me up an elemental, ayup.") The full Great Wheel cosmology—though it wasn't named that at the time—was first laid out in Dragon #8, in the grandiloquently titled article "Planes: The Concepts of Spatial, Temporal and Physical Relationships in D&D", by (who else?) Gary Gygax, co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons. It wasn't much—barely longer than a page, with a single diagram that Gygax himself admitted looked like "abstract art", but it was a start. (It wasn't really abstract art, he clarified, but "a 2-dimensional diagram of a 4-dimensional concept." I'm not sure how he decided it was "4-dimensional"; by my analysis, if each plane is infinite in three dimensions, and if we assume that planes shown as adjacent in the diagram are also literally physically adjacent along some geometrical axis, then the given arrangement of the planes would require at least five dimensions total. But that's not really important.)

Did he... did he color this in with crayons?

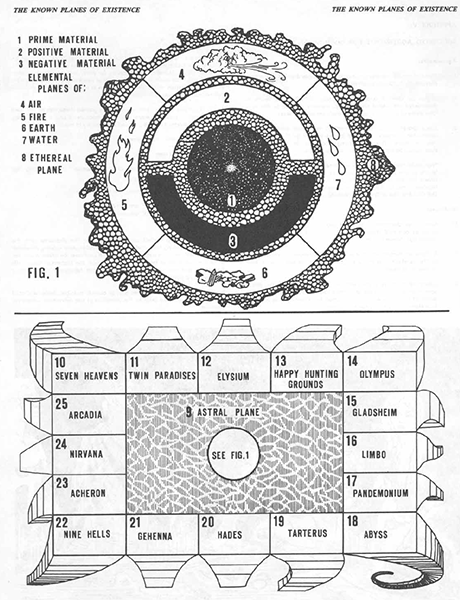

In the first-edition Player's Handbook, "Appendix IV: The Known Planes of Existence" recapitulated the information from Dragon #8; it took up two pages instead of just one and a quarter, but that wasn't so much because it added new information as because it had more spacing between paragraphs and included two large diagrams instead of just one small one.

As it later turns out, the Elemental Plane of Air is not in fact inhabited by living clouds with faces as shown in this diagram. The Happy Hunting Grounds, however, is. (Are?)

But the same couldn't be said of "Appendix 1: Known Planes of Existence" in the first-edition Deities & Demigods, which took up a full six pages. Some of this was, again, due to more tables and diagrams; this appendix included five diagrams, as well as encounter tables for both the Ethereal and Astral Planes and tables for making a random choice from either the Inner Planes or the Outer Planes. But it did also include some new information, including six new planes not mentioned in Dragon #8 or the Player's Handbook: the Plane of Shadow (the distant ancestor of fourth and fifth edition's Shadowfell), the true neutral Outer Plane of Concordant Opposition (later known as the Outlands), and the four Para-Elemental Planes that lay between the four main Elemental Planes. But the influence of Deities & Demigods on the D&D cosmology wasn't limited to this appendix—the fact that it defined homes for each of the gods on the planes had significant consequences for the Manual of the Planes and later Planescape and the D&D cosmology in general.

So that's where we're starting our look at Planescape and its predecessors, with the first-edition Deities & Demigods, by James M. Ward and Robert J. Kuntz. I chose this book not only because of the impact it would have on the D&D planes, but also because, well, there's a lot to say about it. Deities & Demigods was probably the most—I hesitate to use the word "problematic", because it kind of gets overused to the point of near-meaninglessness, but here I think it does apply, so what the hey—problematic book of first-edition D&D. Alongside fantasy pantheons and ancient pantheons like the Greek and Norse, it included rather more culturally insensitive entries like the "Indian Mythos", which described gods still widely venerated today by the roughly one billion Hindus in the real world; and the "American Indian Mythos", which lumped together unconnected traditions from disparate peoples all over the North American continent into one muddled, ahistorical syncretism.

This isn't entirely new to the first edition Deities & Demigods, actually—the fourth supplement to the original D&D boxed set, "Gods, Demi-Gods & Heroes"—not coincidentally by the same authors, though listed in the reverse order—also included most of the same mythoi, including the Indian but not the "American Indian". It also, incidentally, included the mythos of "Robert E. Howard's Hyborea", which did not make it into the 1E Deities & Demigods. I'm not going to give a full review of this supplement—it didn't really have a direct impact on Planescape—, but I will bring it up again; in fact it's going to come up again in the next post.

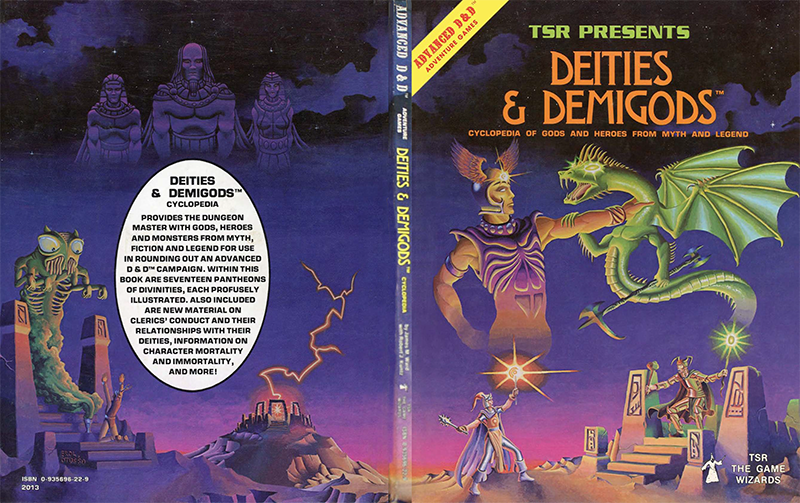

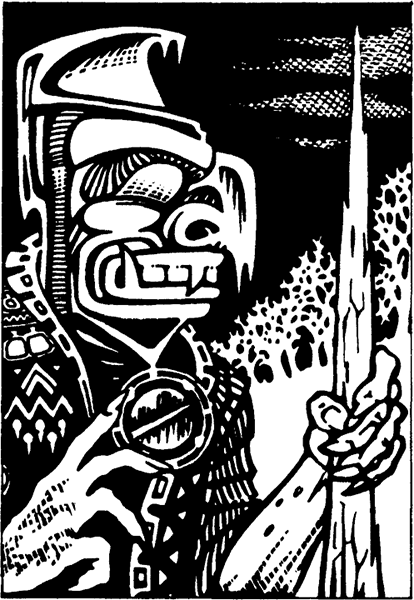

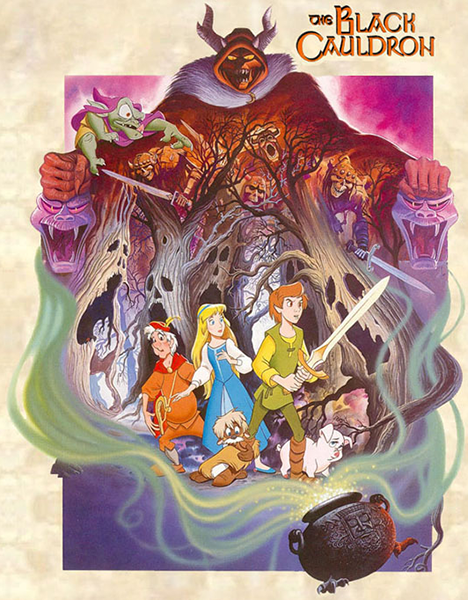

Before we get into the meat of the book, though, let's take a gander at the cover:

I'm pretty sure the two gods on the front cover are supposed to be fighting, but they don't really seem to be into it.

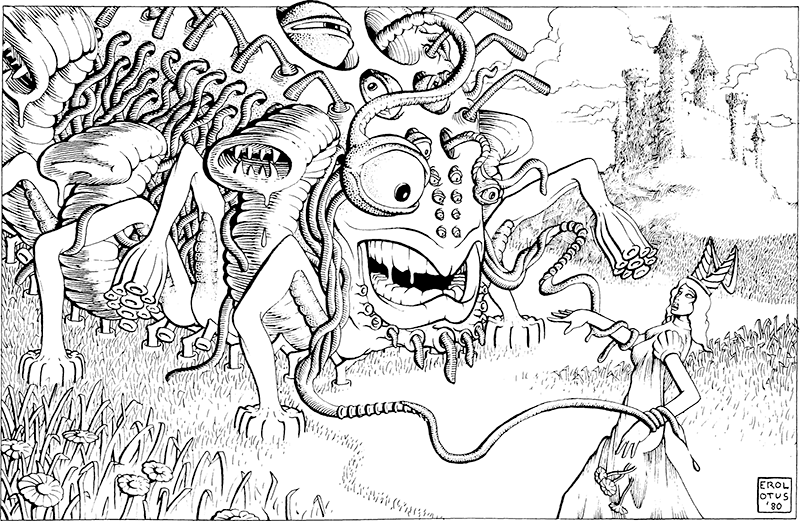

Anyone familiar with the art of first-edition D&D will recognize that as the work of Erol Otus, who definitely has an instantly identifiable style of his own. Otus also did some interior illustrations in some other books and illustrated the cover of the 1981 version of the D&D Basic Set, and did many covers and interior illustrations for Dragon Magazine and some adventure modules. He's also done work for other role-playing game companies, as well as art for some video games, including Star Control II.

None of the entities on the cover actually appear in the book, though. Unless those three gods in the sky are supposed to be Egyptian gods, which... maybe? The middle one could be Ptah, I guess, but I'm not sure who the other two would be.

Incidentally, both credited authors of Deities & Demigods are still alive, and still working to some degree in the RPG industry, though not on Dungeons & Dragons. Both were players in Gary Gygax's original Greyhawk games, and both have been immortalized in the game under scrambled versions of their names. James M. Ward created the first science-fiction role-playing game, Metamorphosis Alpha, released by TSR about the same time as "Gods, Demi-Gods and Heroes". The Greyhawk archmage Drawmij, the eponym of the spell Drawmij's Instant Summons (and several other spells in earlier editions), was named after him—note what you get if you spell "Drawmij" backwards. Robert J. Kuntz, meanwhile, was for a time the co-Dungeon-Master of Gygax's Greyhawk campaign, and contributed heavily to the Greyhawk setting. His player character Robilar not only eventually appeared as an NPC in the Greyhawk setting, but also had a scrambled version of his name attached to a core magic item, the iron bands of Bilarro. Kuntz also was more directly referenced via an anagram of his surname in another NPC, the archmage Tzunk, first mentioned in the third supplement to the original D&D boxed set, "Eldritch Wizardry", as a wizard who wrote about the Codex of the Infinite Planes—although there his name was spelled "Tzoonk"; it was respelled "Tzunk" in the first-edition Dungeon Master's Guide, perhaps to make the homage to Kuntz a little clearer.

Anyway, Deities & Demigods was eventually reprinted under the title Legends & Lore (not to be confused with the entirely different second-edition Legends & Lore... at least TSR didn't reuse old titles to the extent that Wizards of the Coast later would during the third-edition era), but I refer here to the former title because the first printing of the book had two pantheons (or "Mythoi", in this book's terminology) that the later printings, including those under the Legends & Lore title, lacked: the Cthulhu Mythos, based of course on the works of H. P. Lovecraft and his collaborators and imitators, and the Melnibonéan Mythos, based on the stories of Elric of Melniboné by Michael Moorcock. (Actually, Moorcock had an important influence on D&D that's worth discussing... but I'll save that till we get to the Melnibonéan Mythos.) I'd bought the book when it first came out (or rather had it bought for me, I suppose, since I was a young child at the time), and so I had a copy of the printing that included these two mythoi—still have it, in fact, along with all my other first-edition D&D books, though at the moment due to limited shelf space they're in a box in a storage unit. Unfortunately, the book is in pretty bad shape; the spine is missing, and the cover is badly battered, which I'm sure greatly reduces its value to a collector—not that that matters much, since I have no intention of selling it. But anyway, I guess its well-worn condition testifies to how much use this book saw—or at least how much I enjoyed looking through it, since its actual application to a game was somewhat limited.

The obvious explanation for the absence of the Cthulhu and Melnibonéan Mythoi from later printings is that TSR had failed to acquire the rights, and so was forced to remove them. That's not the real story, though; what really happened was more complicated. It's debatable that rights were even needed for the Cthulhu Mythos, which was almost certainly in the public domain by then; Arkham House, a publishing company set up by August Derleth and Donald Wandrei, claimed the rights to Lovecraft's work, but that claim wasn't necessarily on firm legal ground, and it's doubtful that it would have held up against a serious challenge in court. But TSR didn't try to challenge Arkham House's claim, so that's moot. The same couldn't be said of Moorcock, however, who was still alive at the time—and at the time I'm writing this still is—, but TSR actually had contacted Moorcock and obtained his permission to use his characters and concepts. The fact is that it wasn't Arkham House or Moorcock that objected to TSR's inclusion of these mythoi at all—it was another role-playing game company that had officially acquired the rights to those two properties, and wasn't sure it liked the idea of a different company using them. That other game company is, incidentally, still around today, and if you know much about role-playing games you can probably guess who it was.

That's right: Chaosium, publisher of Call of Cthulhu. Call of Cthulhu is now in its seventh edition, but back then was only in its first. (Or was about to be in its first; when Deities & Demigods came out Chaosium was working on Call of Cthulhu but hadn't actally published it yet.) At the time, it was also publishing (or about to publish) a game called Stormbringer, based on the same works by Moorcock that Deities & Demigods drew on for its "Melnibonéan Mythos"; that game is out of print today, but went through six editions (five under the name "Stormbringer", one under the name "Elric!" between Stormbringer's fourth and fifth editions) before Chaosium let the license lapse in 2007. (The original Stormbringer game, incidentally, was co-written by Ken St. Andre, probably best known for his role-playing game Tunnels & Trolls, the first real competitor to Dungeons & Dragons.)

Chaosium's production values were a little lower back then than they are today.

However, when Chaosium threatened legal action, TSR contacted them and worked out a deal. Chaosium would withdraw their objections to TSR's using this material, as long as TSR included them in the acknowledgments. And they did—at the end of the "Credits and Acknowledgments" section of the first printing of Deities & Demigods was the sentence "Special thanks are also given to Chaosium, Inc. for permission to use the material found in the Cthulhu Mythos and the Melnibonean Mythos".

Unfortunately, the next year TSR was taken over by two brothers, Brian and Kevin Blume, who had a very different vision than Gygax (and who would eventually sell their stock to TSR manager Lorraine Williams, giving her a controlling interest in the company—but that's another story). The Blumes didn't like the idea of mentioning a rival company in their own book, and decided they would rather excise those two chapters entirely than leave in the single sentence thanking Chaosium. And so in the second printing they did just that—or they did half of that, anyway. Ironically, when they removed the chapters on the Cthulhu and Melnibonéan Mythoi, they neglected initially to take out the offending "special thanks" that was the whole reason they wanted to remove those chapters in the first place. So the second printing of Deities & Demigods still thanked Chaosium for permission to use material that no longer appeared in the book—as did the third, and part of the fourth, until they finally got around to getting rid of that sentence that had bothered them so much. I'm not sure the Blumes were terribly competent.

So while Legends & Lore was essentially the same book as Deities & Demigods except for the title and the cover and those two missing mythoi from the first printing of the latter, because I'm going to include those two mythoi in my review here I'll refer to the book throughout as "Deities & Demigods". Before moving on, though, I will remark that Legends & Lore had a much blander cover:

I'm not bothering with the back cover this time because it doesn't have any art—just text on a solid-color background.

Anyway, I think this preamble has gotten long enough for a post by itself, so next post I'll get around to actually discussing the contents of the book.

Next Time: Gods and Monsters

Gods and Monsters

Original SA post Deities & Demigods 1EPart 2: Gods and Monsters

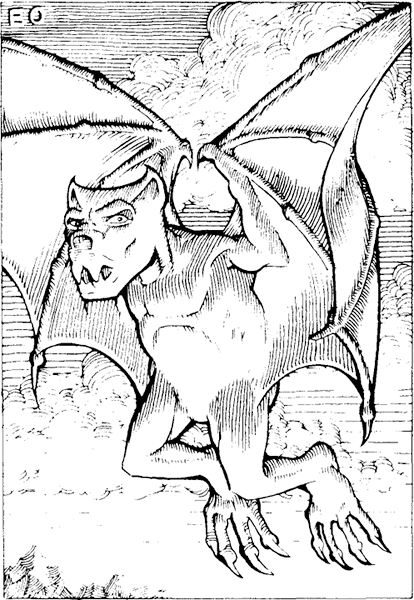

The first thing we see when we open the book (assuming we open it at the beginning) is another piece of art by Erol Otus:

I kind of like to think the entities on the left are good, and the ones on the right are evil, just to play against type. Or maybe both sides are good and it's a dispute of law vs. chaos. Just a friendly disagreement. They're not really trying to hurt each other.

None of these creatures appears in the book either.

Anyway, below that image are the credits, and then we get a foreword by Gary Gygax that lays out the goals of the book.

Gary Gygax posted:

[O]ne particular aspect of fantasy role playing was foremost in my mind: there was either a general neglect of deities or else an even worse use by abuse. That is, game masters tended to ignore deities which were supposedly served and worshiped by characters in the campaign, or else they had gods popping up at the slightest whim of player characters in order to rescue them from perilous situations, grant wishes, and generally step-and-fetch. Obviously, there is a broad ground between these two extremes, and that is squarely where I desired AD&D to go."

He goes on to emphasize just how much input he had into the book and its format, and how closely he supervised the authors to make sure the book matched his vision. Which, incidentally, I totally believe; I think pre-Blumes Gygax was pretty hands-on and protective of his game. I'm not going to quote the whole foreword—it fills most of a page; I don't think anyone ever accused Gygax of being laconic—but there are two other bits I want to highlight. One is that he mentions that the "[d]iabolical and demoniac deities are important to the campaign milieu", but not included in this book, because they were already in the "MONSTER MANUAL and the attendant volumes forthcoming", and it was "no great matter to extract these beings from the other works and include them amongst the other deities"—which seems to imply he intended Dispater and Demogorgon and the other archdevils and demon princes from the Monster Manual to be considered gods on par with Anubis and Artemis. (Actually, that's made more explicit later in the book, in the chapter on Nonhumans' Deities... we'll get to that eventually.) The other thing I wanted to mention is this:

Gary Gygax posted:

It is worth commenting that the strength and powers of the beings contained herein are appropriate to the overall work. Thus, addition of these deities and demigods does not imbalance the campaign. Furthermore, characters who become a match for them are obviously to be ranked amongst their number, no longer suitable for daily campaign interaction, but to be removed to another place and plane and treated accordingly.

So the PCs were not intended to fight the gods, because any PCs powerful enough to fight the gods would ipso facto be gods themselves, and no longer player characters. So then why were the gods given full statistics in the first place? This question is revisited (but not really answered) in the Editor's Introduction—not directly bylined, but presumably by Lawrence Schick, who's credited as the book's editor:

Lawrence Schick posted:

Well, here it is, DEITIES & DEMIGODS, the latest addition to the series of ADVANCED D&D volumes. But what exactly is it? Let's see, it has a nice cover—open it up, inside there are lots of pictures next to sets of stacked statistics . . . it must be just like the MONSTER MANUAL! There, that was easy. Now that we know what it is, we know what to do with it, right?

Wrong.

DDG (for short) may resemble MONSTER MANUAL, and in fact does include some monsters. However, the purpose of this book is not to provide adversaries for players' characters. The information listed herein is primarily for the Dungeon Master's use in creating, intensifying or expanding his or her campaign.

Okay, but again, if the gods aren't intended to be encountered by player characters, why do they have full statistics?

This wasn't the first time this matter had come up. The "Gods, Demi-Gods and Heroes" supplement to the original D&D boxed set had also included full statistics for the gods within—"full" being a relative term, because statistics for anything in the original boxed set were pretty sparse. This matter was addressed in that book by Timothy J. Kask, TSR Publications Editor:

Timothy J. Kask posted:

This volume is something else, also: our last attempt to reach the "Monty Hall" DM's. Perhaps now some of the 'giveaway' campaigns will look as foolish as they truly are. This is our last attempt to delineate the absurdity of 40+ level characters. When Odin, the All-Father has only(?) 300 hit points, who can take a 44th level Lord seriously?

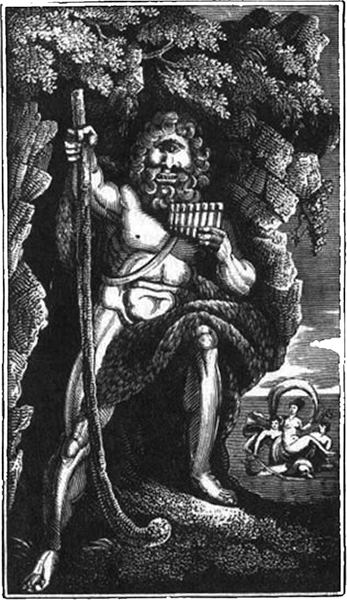

I feel like this post needs more images, so here's the cover of "Gods, Demi-Gods and Heroes"

While this—along with the Editor's Introduction from Deities & Demigods— wasn't written by Gygax himself, it seems a sure bet that Gygax read it and approved it before it saw publication, and that it mostly reflected, or at least didn't conflict with, his own views. But, well, this last rationalization really doesn't seem to me to hold much water. First of all, if you want to highlight how ridiculous high-level characters are, there are simpler means than creating more than a hundred stat blocks you never expect to be used. Second, well, if that was really the intent, the method seems counterproductive. If you provide the players with statistics for anything, at least some players are going to think they're supposed to fight them, no matter how much you try to protest otherwise in the introductory sections that a lot of players are just going to skip over anyway. Stat up the gods, and players will fight the gods. And of course they did.

Not that I did myself, or know anyone who did. I've never been interested in powergaming, and I've never had a character reach nearly that kind of power level—nor has it happened in any campaign I've run as a DM, and I've run long campaigns that went on for real-time years. But my experiences are not universal; there's clear evidence that some players did play in such absurdly high-level campaigns. Early issues of Dragon Magazine include letters from players boasting about their 358th-level characters. That's not an exaggeration: a letter in Dragon #137 began with the sentence "Recently my AD&D® game character, Waldorf, a 358th-level magic-user, created the nuclear bomb." Okay, maybe it's a little bit of an exaggeration, in that I referred to "358th-level characters" in the plural, but while others may not have reported that exact level, some claimed levels that were even higher. In Dragon #31, a writer to the "Sage Advice" column mentioned having "two characters that are at one thousand-plus level". ("I don't know whether to laugh or cry," columnist Jean Wells responded.) And in the same issue as the 358th-level Waldorf, the writer of another letter stated that his friends had "been playing the AD&D game for over six years now" and their characters had "levels in the millions, maximum scores for almost every ability, and can obliterate five planes of the Abyss in a round." (They complained that they were out of challenges, and asked how they could "have fun with these high-level characters." "Perhaps you should meet Waldorf," editor Roger E. Moore replied.)

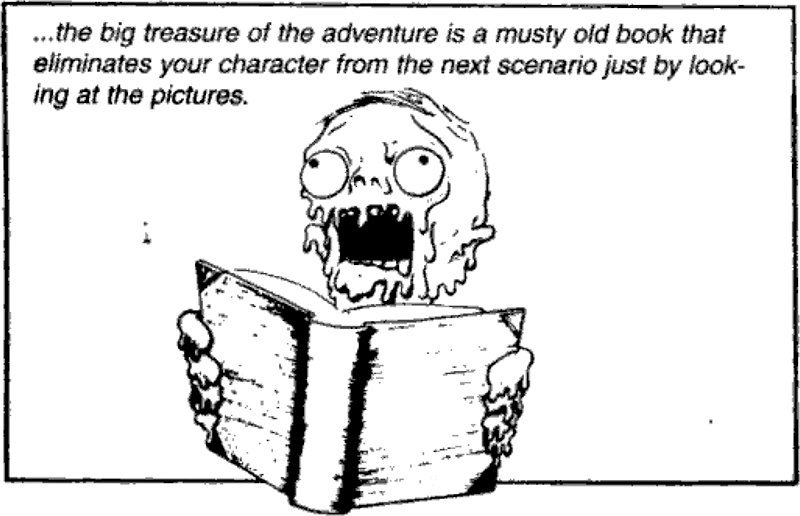

"Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds! Do ho ho ho!"

Actually, those "thousand-plus level" characters are particularly pertinent to the matter at hand, because of how they got to be thousand-plus level. I think I'll just quote that entire letter:

Some silly person posted:

Question: In GODS, DEMI-GODS AND HEROES it says that a forty-plus level character is ridiculous. In our game we have two characters that are at one thousand-plus level. This happened in "Armageddon," a conflict between the gods and the characters. Of course, the characters won. What do you think about that?

In other words, yes, at least some players are on record as having used the book of gods as a book of monsters, having their players gain experience from defeating gods. I'm sure they weren't alone.

But was this really an unintended consequence? On Gygax's part, at least, I'm inclined to say yes. I think Gygax's oft-expressed contempt for such absurdly high-level play was genuine, and that he really didn't intend for players to treat the gods as monsters to be fought. Which, however, again leaves unanswered the main question: Why did they have full statistics?

I think I may have an answer. One thing that gets talked about with regards to early versions of D&D is "Gygaxian naturalism"—the idea that Gygax included a lot of statistics and details in his books not because they had any direct impact on gameplay, but just because they made the world seem more detailed and real. This wasn't really the case in the original D&D boxed set, but certainly was in first edition; monsters frequently had abilities that didn't directly relate to combat; stats and rules and tables were included to deal with all sorts of relatively mundane situation; Gygax's adventures often included notes as to how dungeon features were maintained, even though adventurers were unlikely to discover this. Gygaxian naturalism survived Gygax's own involvement with the company; arguably second edition engaged in it to an even greater extent than first, with monster entries having detailed notes on their habitats and ecologies and even their reproduction, and third edition went so far as to stat up monsters using similar rules to player characters. Of course, this kind of naturalism wasn't unique to D&D, and other games have similarly fleshed out their gameworlds and tried to give them a plausible basis, some to a greater extent than Gygax ever did. So maybe "Gygaxian naturalism" is a bit of a misnomer, but even if wasn't something unique to Gygax, it was definitely something promoted by him. And I can see that as the reason for the gods having stats—if these are something that exist in the gameworld, then by golly they should have statistics (for purposes of naturalism), even if they're never going to be used!

Now, personally, I'm all for Gygaxian naturalism, or whatever you want to call it. To me, a big part of the appeal of role-playing games—maybe the main part of the appeal—is to feel like I'm vicariously experiencing another world, and having the setting feel like a living, breathing environment not entirely focused just around adventures is an important part of that. That's probably why I'm not a big fan of "storygames", or other games that heavily incorporate metagame mechanics; the contrivances they go through to give the players a larger role in defining the gameworld and the environment work against the immersion for me... I don't want, as a player, to be able to influence elements of the surroundings that my character shouldn't have control over, because that undermines the sense of a larger world that doesn't exist just to serve the characters. It's why I don't like "rules light" games that leave much up to DM fiat and narrative convenience; I like having rules for everything, because it bolsters the illusion that there's an objective world where these events are taking place. It's also at least part of why fourth edition was my least favorite edition of Dungeons & Dragons. Yes, it may have been the most balanced edition, but it achieved that balance at the cost of jettisoning any pretense of naturalism; it may be the best edition for games centered around fighting monsters in set encounters and not worrying about what else is going on in the setting, but that's not the kind of game I want to play. (I am not, of course, saying that any of these kinds of games are objectively bad—only that they're not the kinds of games I, personally, prefer.)

So I guess my point, to the extent that I have one, is that while it's easy to poke fun at his including statistics for gods and then not expecting the players to use them, I think I can see why Gygax did that—or more accurately why he allowed (or even encouraged?) the writers to do that under his supervision. I might even have done the same in his place. So what, if anything, should he have done differently? I'm honestly not sure. Maybe been more upfront about his reasons for including the statistics? (Though introspection can be hard, and maybe he wasn't totally aware of his own motives—that's in no way intended as a slam on Gygax; I can't claim to be sure I'm fully aware of my own motives for everything I do either.) Maybe been more explicit about what players and DMs should do about characters who grow too powerful? Or maybe there's really nothing in particular he should have done differently, and the way it was presented served the goals he meant it to serve, and the fact that it also enabled powergaming players who wanted thousand-level characters was an arguably unfortunate but unavoidable side effect.

(Though it may not be directly pertinent to the matter at hand, I feel I would be remiss not to at least mention the existence of the third-edition Deities & Demigods (with its fully statted gods) and Epic Level Handbook (with its rules for characters becoming powerful enough to challenge them). Those books attracted a good deal of mockery and criticism at the time, but they're not completely without precedent; as we've just seen, giving full stats for the gods goes all the way back to the original D&D game. Still, I guess there's a difference between giving stats for gods when those stats are brief enough that you can fit four gods on one page, and giving them when the stats for a single god take up nearly two pages; and while some players may have played ridiculously high-level characters in earlier editions, no previous edition explicitly condoned and encouraged such play the way the Epic Level Handbook did (the closest was probably the Basic D&D Immortal Rules, but even that was less over the top); so maybe the criticism isn't entirely unwarranted.)

Anyway, I've now spent almost two thousand words discussing why the gods have stats. Time to move on.

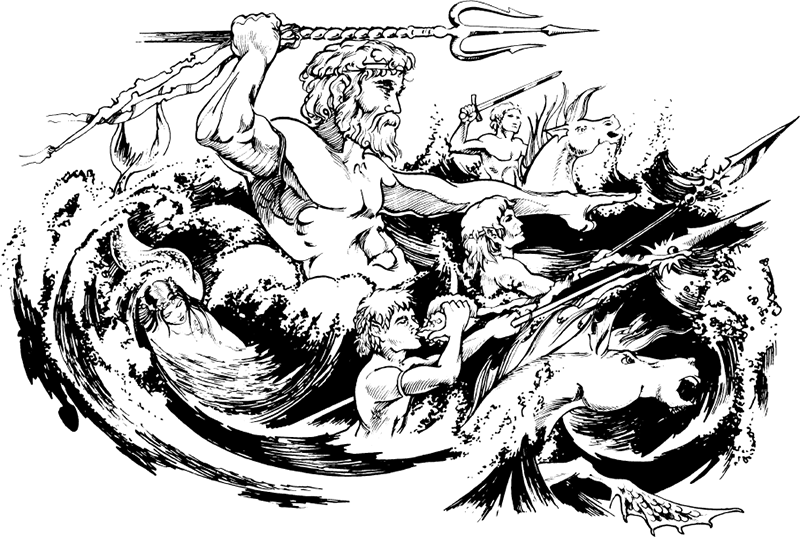

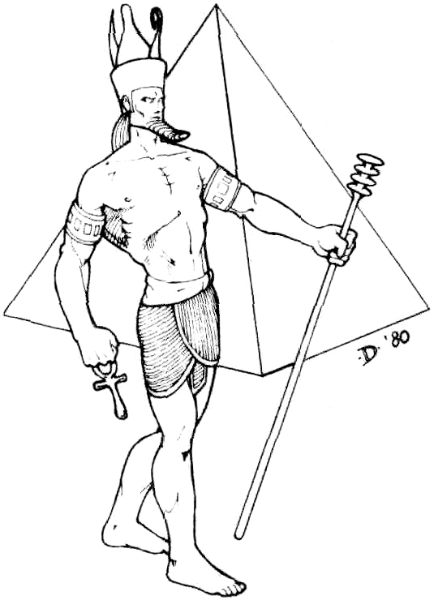

After Gygax's foreword, we come to the table of contents, at the bottom of which is our first piece of art not by Erol Otus. I'm not sure who it's by, actually; while the credits list all the artists, they don't say who did what, and I don't see a signature on this piece—and I'm not sufficiently intimately familiar with the styles of the various 1E artists to recognize it. (If I had to guess, I'd venture it's probably Paul Jaquays (as she was then credited; she now goes by Jennell Jaquays), but I'm not sure.)

He looks kind of bored. "It's a living."

At least, assuming that's supposed to be Poseidon, this time it depicts an entity that actually does appear in the book.

We then get a preface by James M. Ward, who spends much of it discussing (in generalities) his reasons for the creative decisions the authors made in deciding on the gods' abilities and relative power levels. I'll just quote a part of this:

James M. Ward posted:

All of the leaders of the pantheons were given 400 hit points and the rest were scaled down from there; the relative resistance of beings to blows and magic was derived from studies of their battles with natural and supernatural forces; while concepts like strength were easily assigned in the case of deities of strength or war, this concept is less easily applied to the more powerful deities who have no need for massive muscles. Alignments were perhaps the hardest AD&D concept to deal with, and the one that will have the most debate among the interested users of this work. Beings like Set, Loki and Arioch are easy to classify, but when working with the middle-of-the-road deities who were often chaotic but known for consistent kindness, or were rogues of the worst sort but very companionable, it became necessary to consider them as a whole to make a judgment.

Actually, I don't think even Set and Loki were as straightforward as he's making them out to be. Both are usually depicted as evil in modern pop culture, but neither really was evil in the oldest myths. Set was originally a benevolent god of the desert and of warfare, and was widely honored; his name was used for love spells, and he accompanied Ra on his daily journey on the solar barge and protected the sun god by fighting off the evil serpent Apep. It was only after Set was adopted by the invading Hyksos that his association with foreigners, combined with the rise in worship of Osiris, induced the Egyptians to have a more negative view of him. As for Loki, he was certainly mischievous in many of the myths about him, but he was generally a staunch ally of the Aesir, and the only myths in which he did anything outright evil were set during (and just before) the events of Ragnarǫk—which may very well have been at least in part an invention of the Christian mythographers who are the only source we have for these stories.

Anyway, below the preface are the credits, including the aforementioned thanks to Chaosium, and then on the next page we finally get to... the Editor's Introduction. Yes, we have a foreword, a preface, and an introduction, each written by a different person. Don't worry; we don't also have a prologue, a preamble, or an exordium.

I've already quoted the beginning of the Editor's Introduction above; Schick goes on to discuss the vital role that clerics should have in a campaign and the importance of the DM's considering "the flavor of the campaign" when deciding which pantheons to use, and encourages DMs to read up on the mythologies themselves to "discover the fascinating stories behind these immortal characters, and get a really solid feel for how to play them." There's one odd statement I want to highlight:

Lawrence Schick posted:

The most important thing to remember about this book is that, unlike the other AD&D volumes, everything contained within this book is guidelines, not rules. DDG is an aid for the DM, not instructions.

I'm honestly not sure exactly what Schick is getting at here. Surely in some sense every book contains guidelines, not rules, but why is this more true of Deities & Demigods than any of the others? Gary Gygax was never going to come to your home and force you at gunpoint to roll a loyalty check for your faithful henchmen when you left them in a position where they could potentially steal your silverware. I think what Schick means is that you can choose which gods and pantheons to use in your campaign, and you can change their alignments and abilities if it works better for your purposes, but the actual rules regarding gods are just as much rules as anything in the Player's Handbook or Dungeon Master's Guide.

Anyway, after the Editor's Introduction we now finally get to the "Explanatory Notes", which... I guess I'll save for another post, because this one got long enough as it is. (Admittedly mostly because of the long digression about the gods having statistics.) Sorry.

Next time: The Consequences of Negative Charisma

The Consequences of Negative Charisma

Original SA post Deities & Demigods 1EPart 3: The Consequences of Negative Charisma

I probably should have been using this banner from the start... oh well.

Foreword, preface, and introduction finished, now we finally get to the meat of the book. Oh, we don't get to the gods themselves yet; no. First we've got to get through the:

EXPLANATORY NOTES

This section details the statistics given in each entry for a god or monster. Some of these statistics apply only to gods, others only to creatures, but they're all mixed together in these notes. Most of these are straight out of the Monster Manual and other early monster books: Frequency, Number Appearing, Armor Class, Move (with the quirky 1E convention of preceding the movement rate with a slash to indicate flying speed, two slashes for swimming, etc.), Hit Points, Hit Dice, % In Lair, Treasure Type, Number of Attacks, Damage per Attack, Special Attacks, Special Defenses, Magic Resistance (in 1E Magic Resistance was a standard item in every monster entry, even though the vast majority of monsters didn't have it), Intelligence, Size, and Alignment. We do get a few notes on possible special values for these items for gods: Move, for example, could be Infinite, indicating that "the entity can travel to any point desired with no time lapse, and this is the being's preferred mode of movement." We also get a description of how Magic Resistance interacts with deities' special abilities—surprisingly, it still applies. After Alignment we get our first item that hasn't been standard in monster books: Worshiper's Align, the typical alignment of worshipers of the god, which may or may not be the same as the alignment of the deity. ("This does not necessarily apply to the alignment of the deity's clerics, which must be identical with their patron's.") After that we get Symbol ("Fairly self-explanatory, this is the symbol by which the deity and his or her faithful followers are known. It will be found engraved upon most holy items."), and then Plane—the "deity's plane of origin", usually, but not always, one of the Outer Planes. After that, for deities and heroes we get their levels of ability in various classes and subclasses: Cleric/Druid, Fighter, Magic-User/Illusionist, Thief/Assassin, and Monk/Bard. (It's worth noting that the gods and heroes in this book do not apparently make any attempt to follow standard AD&D multiclassing/dual classing rules—which were, admittedly, messy and contrived anyway.) We then get Psionic Ability—like Magic Resistance, a standard item in 1E monster entries, even though it didn't apply to the vast majority of monsters (though most of the gods do have some level of psionic ability)—and finally, for gods and heroes, their ability scores: Strength, Intelligence, Wisdom, Dexterity, Constitution, and Charisma (abbreviated by their first letters, except Charisma, which is CH).

The ability scores get a little over a page of extra explanation, because while the Player's Handbook laid out the bonuses and penalties of ability scores ranging from 3 to 18, gods and heroes often had higher ability scores. Therefore, this book extends the tables from the Player's Handbook to include ability scores from 19 to 25—25 was a hard cap on ability scores in 1E, as 30 is in 5E. For example, characters with a Strength of 25 can carry 15,000 pounds, get a +7 bonus to hit and +14 to damage, and have a 23 in 24 chance of forcing open a stuck door (or 9 in 10 if it's locked, barred, magically held, or wizard locked). Characters with a Dexterity of 25 get a +5 adjustment to attacks, a −6 defensive adjustment to Armor Class (in 1E, lower armor classes were better), and bonuses ranging from 30% to 50% to the various thief skills.

Charisma is unique in that it gets extended to values not only above 18, but also below zero. "In certain instances," the book explains, "some divinities are so loathsome and repellent as to actually have negative charisma." For example, a being with a Charisma of −7 gets a reaction adjustment of −70%—meaning that 70% is deducted from the probability of an NPC's having a positive reaction to the character. Gods, but not other characters, also have a horror ability if they have a negative charisma, causing creatures below a certain threshold of hit dice or levels (12, for a Charisma of −7) to be "stunned with fear and detestation until the being is no longer in sight"—divine beings with a high positive Charisma, incidentally, have a differently flavored but mechanically identical awe power. Oddly, neither Deities & Demigods nor the Player's Handbook addresses the effects of Charisma between 0 and 2; apparently you can have a Charisma of −1, or you can have a Charisma of 3, but nothing in between.

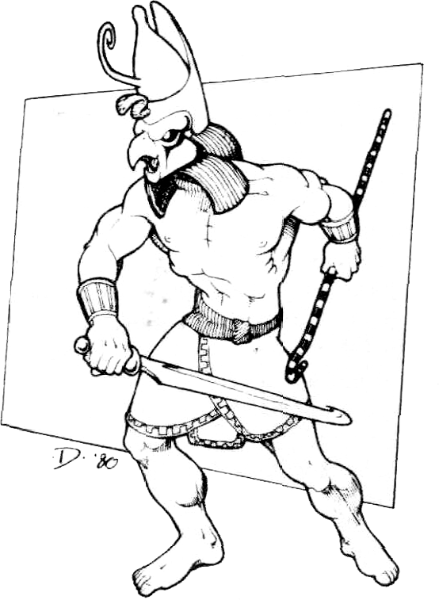

After the Explanatory Notes, we have the Standard Divine Abilities—as well as another image, while I'll include here because I realize that other than the banner at the top I haven't included any images yet in this post (but this introductory text in Deities & Demigods is really light on illustrations—there'll be more once we get to the actual pantheons).

So is this drawing trying to make an analogy between role-players and gods? Because that seems really... trite.

STANDARD DIVINE ABILITIES

Basically, there are eight special abilities that all gods have, unless specified otherwise: they can command other creatures, with no saving throw; they can comprehend languages; they can unerringly detect alignment; they can gate in other beings of the same mythos; they can impose a geas or a quest (these were both spells in first and second edition, with similar but slightly different effects, so this counts as two different abilities); they can teleport; and they have true seeing, the ability to see all things as they truly are (also a spell... in fact, all these abilities are based on spells). These abilities all "function instantaneously and at will, but not continuously." The book also encourages DMs to give the gods "bonus powers" not listed in the book according to their judgment. Finally, all gods and demigods make all saving throws on a roll of 2 or higher on a d20; heroes need a 3.

DUNGEON MASTERING DIVINE BEINGS

Dungeon Mastering Divine Beings posted:

In AD&D, when the deities deign to notice or interfere with the lives of mortal men, it is the Dungeon Master who must assume their roles. DMing a divinity presents a far greater challenge than playing the role of a merchant, a sage, or an orc. Players will quite naturally pay special attention to the words and deeds of the gods, so the DM must make a special effort to understand how to present them.

Basically, we're told that the gods are egotistical beings who will harshly punish any mortals who try to intimidate them or treat them as equals. They "enjoy flattery, but any any god with a wisdom score above 15 will know it for what it is, and will generally not allow his or her opinion of the flatterer to be altered by the flattery." Most gods have much higher Intelligence and Wisdom than mortals, and shouldn't be easy to trick or fool. "In fact, as DM, you can usually assume that if you know why a character is saying or doing something, the deity would know it as well. This should help to simulate the deity's superior intellect and wisdom, and impress the characters." Gods rarely deign to enter combat with mortals, and even if they do they won't risk their lives, and are likely to just summon aid and then teleport away. Nor will they typically fight other gods, "[u]nless they have a history of mutual antipathy".

Gods are willing to aid their worshipers, but usually do so in subtle ways rather than by overt miracles, much less personal appearances.

Dungeon Mastering Divine Beings posted:

If the supernatural powers of the various Outer Planes could and would continually and constantly involve themselves in the affairs of the millions upon the Prime Material Plane, they would not only be so busy as to get neither rest nor relaxation, but these deities would be virtually handling all of their own affairs and confronting each other regularly and often. If an entreaty for aid were heard one time in 100, surely each and every deity would be as busy as a switchboard operator during some sort of natural disaster. Even if each deity had a nominal number of servants whose purpose is to supply aid to desperate adventurers, the situation would be frenzied at best. It is obvious that intervention by a deity is no trifling matter, and it is not to be allowed on a whim, even if characters are in extremis!

Nevertheless, it's not entirely impossible that a god might come to a character. Evil gods are particularly likely to appear, if they think they can make converts; good gods are more likely to send servants. The book does something very interesting here and suggests that the increased abilities of high-level characters are in fact due to direct divine intervention: "the accumulation of hit points and the ever-greater abilities and better saving throws of characters represents the aid supplied by supernatural forces." I guess that's one way to answer the pervasive question of what hit points really mean in the game world, but for better or for worse I don't think this was ever followed up on. (To be fair, the 1E Player's Handbook had mentioned "luck (bestowed by supernatural powers)" among the things that hit points above first level were supposed to represent, but Deities & Demigods seems to suggest that that's all they are.) In any case, this goes two ways; gods regard high-level characters as important resources, which means they may call upon those characters to do things for them. "In these cases, rather than being requesters of divine intervention, characters may actually become part of the intervention itself!"

This section ends with a discussion of the chances of a character's receiving divine intervention when requested, and it's... actually much higher than the preceding text would seem to indicate, at least for first-time petitioners.

Dungeon Mastering Divine Beings posted:

If the character beseeching help has been exemplary in faithfulness, then allow a straight 10% chance that some creature will be sent to his or her aid if this is the first time the character has asked for (not received) help. If 00 is rolled, there is a percentage chance equal to the character's level of experience that the deity itself will come, and this chance is modified as follows:

And then we get a bunch of modifiers to the chance: minus 5% for each previous intervention, plus 1% if the character is "opposing forces of diametrically opposed alignment", etc. We also get a note that this applies only to activity on the Prime Material Plane, or occasionally in the Astral and Ethereal; gods never intervene directly on the Outer Planes or the Positive or Negative Material Planes, and "intervention in the Elemental Planes is subject to DM option, based on the population he or she has placed there."

CLERICS AND DEITIES

Here we get information about the relationship between, well, clerics and deities. Most of this is fairly predictable stuff: gods expect their clerics to "maintain appearances and perform the proper rituals"; clerics may be expected to build places of worship for their gods; etc. One bit worth noting is that not all clerics have access to all spell levels; there are essentially three tiers of godhood, and only the highest tier, "greater gods", can grant their clerics spells up to seventh level (the highest level of cleric spell that existed in first and second edition). "Lesser gods" can only grant up to sixth level spells, and "demigods" only up to fifth. Personally, I think back when I played first-edition D&D I just ignored this fiddly and annoying rule, and I'm sure I'm not alone in that. (Not that it would have come up much anyway; clerics of sufficiently high level to cast sixth- or seventh-level spells were few and far between.) We're also told that first- and second-level spells come directly through the cleric's own faith and knowledge; third- through fifth-level spells are granted by divine servants; and sixth- and seventh-level spells are bestowed directly by the gods themselves... but it's not clear that this has any actual game effect. (Well... I guess the part about first- and second-level spells not requiring the deity to grant them does turn out to have one game effect that we'll get to later, but it's one that would only come up in extremely unusual circumstances.)

We then get a discussion of what happens if clerics fall away from the path of their deities. Basically, low-level clerics don't really need to worry about divine punishment; the gods expect more from higher-level clerics. (Although the book doesn't say so, I'm assuming that applies only to relatively minor transgressions; if a low-level cleric decides to go on a spree of desecrating the temples of his or her god and wantonly slaughtering the god's other worshipers, I would expect the god might actually raise an objection to that.) For such a cleric, a minor lapse can result in nothing more than an admonitory omen on first offense. (We'll be getting to omens in a moment.) If the trespass is repeated, however, the god may send a servant to require the cleric to undergo penance—which may be as simple as an atonement spell if the cleric wasn't really at fault (yes, this was a spell in earlier editions), and otherwise may involve "several days of fasting, prayer and meditation and/or minor sacrifices." More weighty infractions may require major sacrifice, minor quests, or, in some religions, "public degradation and humiliation"; really serious offenses may require the cleric to "sacrifice all of his or her possessions and then go on a major quest in order to restore good standing." And of course, really serious sins or heresies may result in excommunication or even "direct divine wrath".

So... really pretty much what you'd expect, although we're assured at the end of this section that a "faithful and true cleric... does not even consider committing actions which oppose those of his or her alignment and religion."

OMENS

And now we get a section on omens, "signs or indications from deities that display the pleasure or displeasure of the gods or serve to foretell the future." Oddly, we're told that this section "deals with many of the common omens of historical reality", by which I assume the authors mean phenomena that were historically believed to be omens, unless they really think that gods constantly dispensing omens is a part of genuine, real-world history. Players who act against their alignment will be sent bad omens, most commonly in the form of a slight loss of power. (Yes, the book says players, but of course it no doubt means player characters... there are a lot of things here that could be worded better.) This isn't limited to clerics; unfaithful fighters may lose half their hit points due to illness, magic-users may be unable to cast their higher-level spells, and so on. The importance of getting the player characters to stick to their alignments is really hammered hard here:

Omens posted:

In short, omens are devices for judges [i.e. DMs] to use in correcting players that constantly do improper things in the campaign. If a temporary loss of power does not deter a player from constantly violating his or her alignment or not following the ways of the deity, then more severe omens can be given or the effects of some can be made permanent.

We then get lists of common omens, though we're assured that they're "entirely optional", and that:

Omens posted:

Under no circumstances should a player be allowed to badger a DM into, for example, giving the player a bonus on saving throws simply because he or she is carrying a pouch full of four-leaf clovers! In the AD&D universe, such an occurrence might foretell seven years of ill fortune to follow.

First we get the good omens, and it's... not really particularly interesting. Yes, four-leaf clovers are there, along with dice, crossed fingers, "and the three apes that see, hear, and speak no evil", inter alias. We do get the interesting note that "[t]he wearing of leather from top to bottom is said to repel demons and devils"—which is given no hard rules to back it up, and, again, is never followed up on. Bad omens, we are told, are more numerous than good, and include standard superstitions such as breaking mirrors, spilling salt, and "[t]hirteen of anything in one group". Rather oddly, we're told at the end of the paragraph that "[t]he coming of a will-o'-the-wisp is interpreted to mean that some building is going to burn to the ground within seven days, while the wail of a banshee certainly means that someone is going to die that very night." Well, according to the Monster Manual, will-o'-the-wisps and banshees are evil monsters that want to kill you. I think calling them bad omens is kind of redundant.

Save versus magic or be instantly killed by this bad omen.

In between the good and bad omens, dung for some reason gets a whole paragraph.

Omens posted:

Dung is said to have both good and bad properties. Objects or persons that are covered in dung reputedly cannot be touched or hurt by the undead. On the other hand, if even a small bit of dung is cast upon an altar consecrated to good, the altar is defiled and only evil can be contacted there. The forces of good must go to great lengths to resanctify such a tainted object.

The appearance of a rainbow, by the way, is a "definite statement from a deity. Its appearance means either that the deity wants to converse with a mortal, or that the deity wants the mortal to undertake a quest." So apparently in the D&D multiverse, every rainbow is a direct miracle specifically sent as a message from a god—at least according to this book, and no other D&D book ever. (One wonders how the mortals who see the rainbow know who the rainbow is specifically intended for, and what the quest is they're supposed to undertake. Perhaps D&D rainbows don't have a standard ROY G BIV order, but are color coded to signify their meaning.)

"Hm... blue red blue yellow purple green orange red. Welp, looks like Oghma wants Finn to go slay a hag."

MORTALITY AND IMMORTALITY

The last major section of the introduction is "Mortality and Immortality". This section begins by discussing the difference between souls and spirits—a technicality that existed in early editions of D&D, but was dropped from third edition on. Basically, only humans, dwarves, halflings, gnomes, and half-elves have souls; all other creatures that worship gods—including elves—have spirits. (Apparently creatures that don't worship gods don't have either souls or spirits, and are just gone when they die. Or they have some third, unspecified type of vital force (or anima, as the book calls souls and spirits collectively). Pneuma? Quintessence? And yes, we are given some brief guidelines for deciding whether or not a given type of creature worships deities.) Creatures with souls can be restored to life by a raise dead or resurrection spell; creatures with spirits cannot. (We are, however, assured that this system "is only a suggested one", and that "[i]ndividual Dungeon Masters should use a different system if they find this one unsuitable.")

Yes, that means in first and second edition elves could not be raised or resurrected. That part isn't actually new to this book; it was in the Player's Handbook—though that's another rule that I'm guessing was probably widely ignored. What is new to this book is the more detailed account of what happens to souls or spirits after death. Both souls and spirits go to an Outer Plane, usually the one where their deity resides, and more specifically to the part of that plane where the deity's influence is strongest. (Yes, there does seem to be an assumption throughout this book that every character will necessarily be devoted to a single god; characters who worship multiple gods or who don't bother worshiping any gods at all apparently don't exist.) The soul or spirit of a person who has not been perfectly faithful to his or her deity's tenets, however, may instead go to a different plane more in keeping with the character's true alignment. Once they get to their destination plane, souls are there for good; spirits, however, are eventually reincarnated and returned to the Prime Material Plane, though not necessarily as the same species as they used to be. The timing of the reincarnation is unpredictable: "It could range from as little as ten years to a millenium [sic] or more—time is not important to a deity."

(Speaking of reincarnation, it just occurred to me that the first- and second-edition reincarnate spell interacts weirdly with the soul/spirit distinction. The reincarnate spell could potentially bring back a dead human as an elf, or vice versa; does that mean the subject's soul was transformed into a spirit, or the reverse? Or does that result in a human with a spirit, or an elf with a soul? For that matter, the druid version of the spell could also bring back a dead human or elf as, say, a badger, or a raccoon (though I don't think any first-edition book ever had game statistics for raccoons); if badgers and raccoons don't normally worship gods, and hence don't have souls or spirits, is the soul or spirit of the reincarnated individual destroyed, or does he or she come back as a uniquely ensouled/enspirited badger or raccoon? Maybe these questions were addressed in a "Sage Advice" column somewhere, but if so I'm unaware of it.)

We're then given this parenthetical paragraph:

Mortality and Immortality posted:

(Note: The above is only a suggested method for dealing with character life-after-death. The DM may, of course, use whatever system is most appropriate to his or her campaign.)

Yes, we were already told a few paragraphs ago that this system was optional, but apparently the authors found that important enough to warrant reiterating. Okay, maybe the Editor's Introduction really meant what it said about everything in this book being guidelines, not rules after all.

Anyway, the soul or spirit is not instantaneously transported to an Outer Plane immediately upon a person's death. Rather, it has to travel through the Astral Plane, a process that takes 3-30 days. (At least, we're told that's the time "relative to those in the Prime Material Plane", but "time is meaningless to the soul or spirit". Which means... what, exactly? Does the soul or spirit experience it as instantaneous travel? Does the soul or spirit just have no idea at all how much time had passed?) This is why it's harder to bring people back with the raise dead spell the longer they'd been dead; the farther along they are in their travel to their destination plane, the farther they are from the Prime Material Plane. The resurrection spell works differently, though, and rather than calling back a soul in transit actually brings it back from the plane of its deity.

Mortality and Immortality posted:

As this involves the cooperation of the deity on the plane where the soul was, clerics must use extreme caution in employing this spell. If a cleric resurrects a being of radically different alignment, the cleric's deity (who gave the cleric this power) may be greatly offended. Similarly, if a cleric resurrects a being of different alignment simply to serve the purposes of the cleric or his or her deity (to extract information, for example), the deity on the plane where the soul was may be highly displeased and may take appropriate action.

So, wait, if resurrection requires the cooperation of the deity where the soul is, can't that deity just not cooperate if it doesn't want the person resurrected, rather than allowing it to happen and then getting all huffy about it afterward? Apparently not, I guess.

Two other notes about souls and spirits before moving on: First, we're told that the soul or spirit's journey through the Astral Plane can be dangerous because of the monsters that "roam the ethereal and astral planes at will" (why are the monsters that roam the Ethereal Plane relevant, if the soul is only traveling through the Astral?), and that this "is why burial chambers often include weapons, treasure, and even bodyguards to protect the soul on its journey." Second, we're told the following:

Mortality and Immortality posted:

The servants, functionaries, and minions of some deities (demons, devils, couatl, ki-rin, titans, and others) are actually spirits put into those forms for the purposes of the deity. It should be noted that the forms listed in the MONSTER MANUAL are by no means the only ones these servants can take — some chaotic deities rule planes where no two beings have the same form!

Which is another thing that was never really followed up on in later books, and in fact ends up being at least partly contradicted by them. Yes, we do later get details of how demons and devils are formed from the souls of the dead, but that seems to be a sort of quasi-natural process rather than an act of the gods, and there's no indication that couatls and ki-rin are formed similarly (and titans, at least, get an entirely different origin). Oh well.

We then get to what immortality means in D&D: basically, an immortal being doesn't age, but that doesn't mean it can't be killed. Whether a god appears old or young has nothing to do with the god's power level. Gods and their servants travel through the Astral Plane anchored by a "silver cord" similar to that of an astrally traveling mortal, except the god's silver cord is unbreakable. (The silver cord was another whole weird thing from early editions of D&D... I won't explain it now, but we'll get into it when we get to Appendix 1.) If the god or spirit is slain on another plane, the silver cord snaps it back to its home plane near-instantaneously and it's not destroyed, but it is weakened: even a greater god will need a few weeks of rest and recuperation, during which time any clerics of that god won't be able to recover any spells above second level. Any divine servant or even god is destroyed utterly if slain on its home plane, beyond even the power of the deities to restore. However, "[a]ll creatures are most powerful in their own territory", and it should be virtually impossible for a god to be killed on its home plane by anything other than another god.

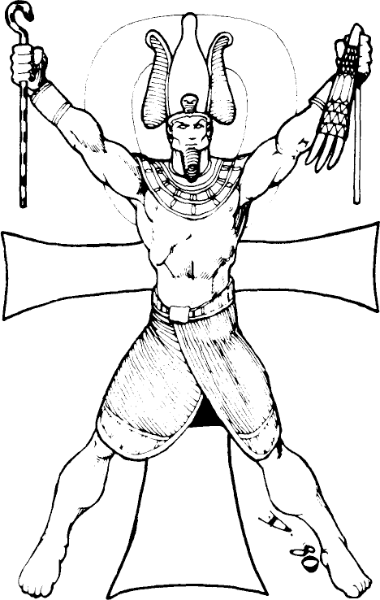

The very last part of the introduction, a subsection under "Mortality and Immortality", deals with Divine Ascension. In other words, we get to find out how a mortal can become a god. Basically, there are four requirements for this to happen:

- The character must be significantly above the average experience level of "adventure-type characters" in the campaign. "(This includes all such non-player types as military leaders, royal magic-users, etc.)"

- The character must have had his or her ability scores somehow raised to be on par with those of the "lesser demigods"

- The character must have "a body of sincere worshipers"

- The character must "be and have been a faithful and true follower of his or her alignment and patron deity"

Mortality and Immortality posted:

This process of ascension usually involves a great glowing beam of light and celestial fanfare, or (in the case of those transmigrating to the lower planes), a blotting of the sun, thunder and lightning, and the disappearance of the character in a great smoky explosion.

Although in this illustration it kind of looks like both are happening at once?

No description of what the process involves for characters that are neither good nor evil. (And yes, as we'll see, there are plenty of gods that are neither good nor evil, and there are Outer Planes corresponding to such alignments, so this does seem to be a significant oversight.)

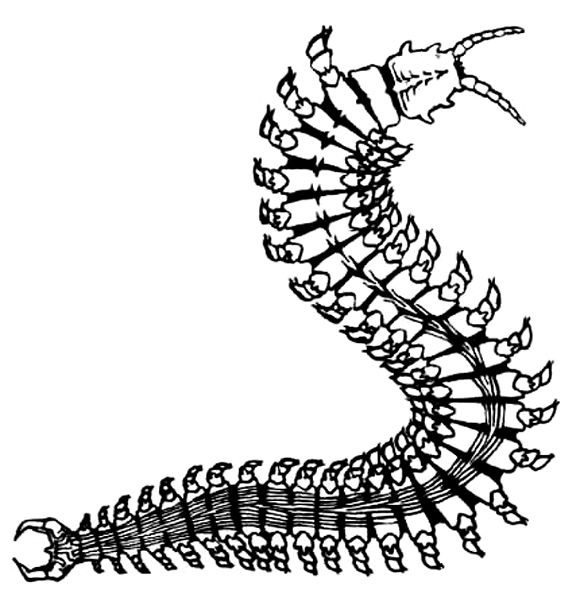

Of course, a PC who ascends to divinity becomes an NPC. Still, I guess that's a better way for a character to retire than failing a saving throw against a giant centipede's poisonous bite.

Save versus poison or be instantly killed by this common ¼-hit-die monster. (Okay, you get a +4 to your saving throw, but still...)

And that's that. Whew. Okay, I'm very glad to be through with all that introductory matter. Maybe I should have split it into more than one post, but honestly I'm just glad to get it done. Starting next post, we'll finally get into the actual pantheons.

Next time: Haida, Iroquois, Navajo... those are all basically the same thing, right?

Haida, Iroquois, Navajo... those are all basically the same thing, right?

Original SA post Deities & Demigods 1EPart 4: Haida, Iroquois, Navajo... those are all basically the same thing, right?

We start out with a bang, with one of the worst-handled "mythoi" in the entire book: the American Indian Mythos.

Or as the title seems to have it, the AMERICAN...indian mythos

As I've already mentioned, this is a grab-bag of figures and concepts from different Native American peoples, all jammed incoherently together. And we start out with a solemn reiteration of the standard cliché of Native Americans being close to the land:

American Indian Mythos posted:

The gods of the Indians of North America were as close to nature as their worshipers could make them. The natural world is the most important aspect of the Indians' existence. The gods will always prefer to appear in the form of a creature of the land. They can, if necessary, appear in human form, but such appearances require great energy and may only last a short time.

Please note that this last bit about the gods rarely taking human form is flatly contradicted in the descriptions of the gods themselves. Of the nine gods in this section, six are described as typically taking human form; a seventh doesn't have his form explicitly described but is depicted as humanoid in the illustration (and is said to use a shield and a bow or hand-axe, which would seem to be difficult for a four-legged animal). This leaves only two gods out of nine that "prefer to appear in the form of a creature of the land"—though they happen to be the first two gods listed.

The text goes on to tell us that "Indian" clerics wanting to control something must have a part of that thing already; that "the symbolism of a name is very important to the Indians", and that "[a]ll Indian rituals involving demons or devils require the use of a large fire for control of the creature." (Nothing further is said as to under what circumstances "Indians" would perform rituals involving demons or devils.) "Rituals revolve around the seasons", we are told, and "[f]ood, finely made jewelry, weapons used successfully in battle and the like are burned at these times for the good of the tribe in the upcoming season." This is all, frankly, pretty generic stuff—generic enough that I can't even say if it was based on the practices of a particular Native American people; it just seems like boilerplate priest-of-a-"primitive"-culture stuff. Clerics dress with magical symbols, which are "buried with the cleric in the event of his death"; young clerics go into battle while older clerics call upon the gods for aid... none of this is particularly interesting or evocative. At the end we finally get to some things that at least sound pop-culture-Native-American: we get a reference to "the warpaint of the warriors" (which, to be fair, really was fairly widespread among Native Americans, though obviously it had different meanings and details in different areas), and are told that "the tent or lodge of the cleric(s) is a place taboo to the rest of the tribe and supposedly guarded by strong spirits."

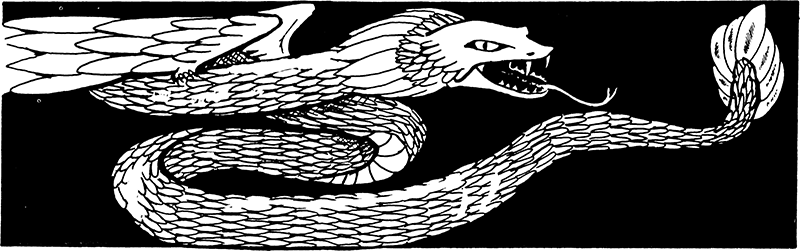

And then we get a couple of paragraphs about "sacred bundles", which in real life I think were mostly confined to some of the tribes of the Great Plains (and, apparently independently, in parts of Mesoamerica, but that's not covered in the "American Indian Mythos"—there's a separate chapter for the "Central American Mythos", which we'll get to later). This is... actually pretty flavorful, if not necessarily faithful to real Native American beliefs, and pretty blatantly overpowered. A warrior makes a sacred bundle with the help of a cleric and a summoned spirit, and it gives significant benefits: +2 on all saving throws, an armor class of 2 (equivalent in first-edition to Plate Mail +1), one point subtracted from every die of damage taken in battle, and the character has only a 1 in 6 chance of being surprised. The bundle contains 5 to 10 items, and... what the hey; I'll just quote the last paragraph:

Sacred Bundles posted:

There are always from 5 to 10 items in a bundle, and the summoned spirit chooses several of the items so that they are very dangerous to secure (thus proving the worthiness of the supplicant). Things like a rattle from a cave of giant snakes, a feather from a high nesting giant eagle, or the hair of 13 enemies killed in battle are the type of items that go into a sacred bundle. When all of the items have been acquired, the priest of the tribe must be brought; he will demand that the last offering placed in the bag be of his choosing. This thing is always something that the priest can use a part of for his own purposes.

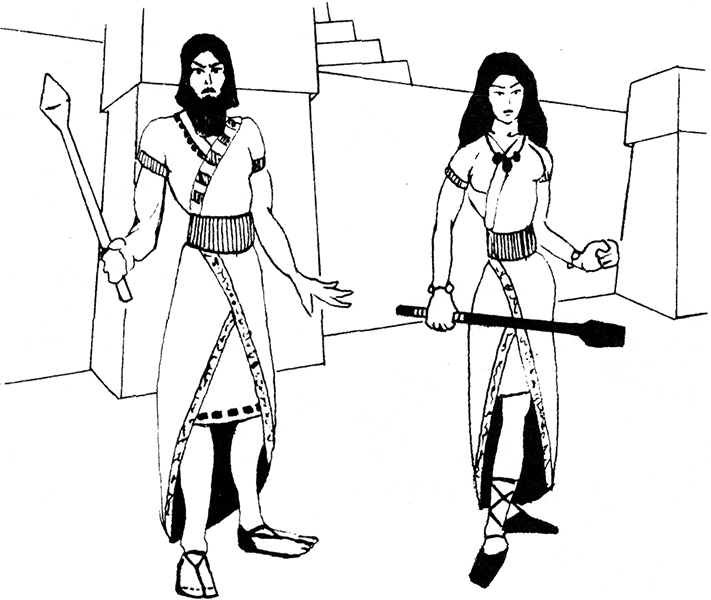

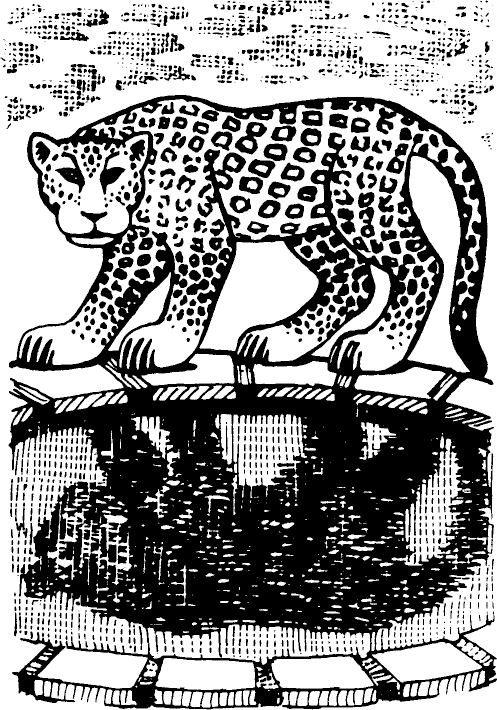

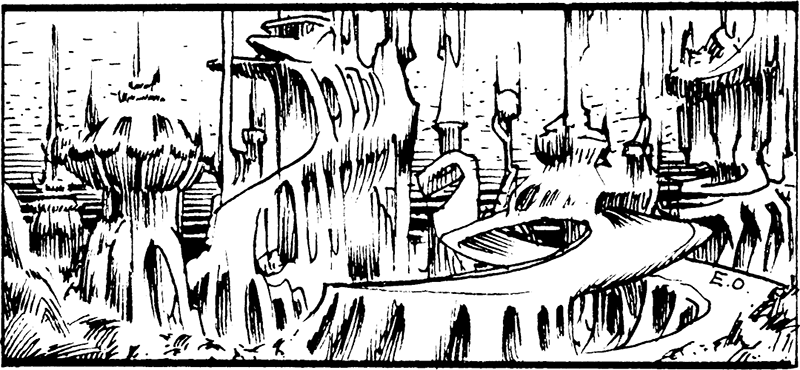

Wait... is that an "E.O." down at the bottom? Is this an Erol Otus drawing? Huh. Doesn't look like his usual style.

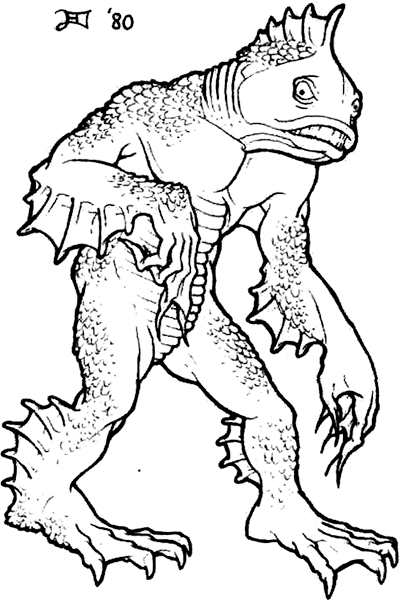

Now for the gods. In contrast to most of the pantheons, in which the gods primarily inhabit the Outer Planes, most of the "American Indian" gods make their homes in the Prime Material Plane. They're a mixed lot, though, and look pretty playable; all the alignments are represented among the gods except lawful neutral and neutral good. There's no information, however, about relationships between the gods, or how they interact with each other—which in one way is understandable, as the gods are drawn from several different traditions. The book does not specify which particular Native American culture each god is from, or in any way acknowledge that there is more than one Native American culture, but I've tried to track down the origins of each god and I'll state them as we go. (I am not, however, by any means an expert in Native American anthropology, and I may get some details wrong.)

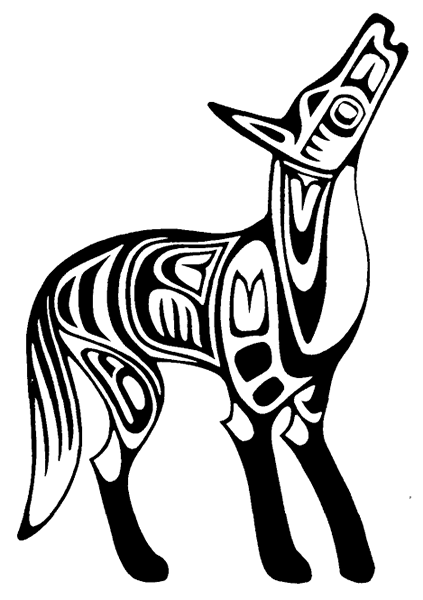

RAVEN

Ah, distinctly I remember, in the marshes of Marsember...

In most of the pantheons, the head of the pantheon comes first, and the rest of the gods are listed alphabetically. In the "American Indian Mythos", Raven is listed first, out of alphabetical order, implying that he's in some sense the head of the pantheon, though this isn't specifically addressed in the text.

Raven is chaotic good, though he is worshiped by people of all alignments, and makes his home in the Elemental Plane of Air for some reason. He's a 12th-level cleric, a 12th-level druid, a 10th-level ranger, a 16th-level magic-user, a 16th-level illusionist, and a 14th-level thief, and—in accordance with what's mentioned in the preface about the leaders of pantheons—he has 400 hit points, more than any other god in the pantheon (though Shakak, whom we'll get to later, is a close second with 390).

Raven is "the great transformer-trickster who is responsible for the creation/transformation of the world". His big thing is shapechanging—both himself and others. He can change his own shape to "appear in virtually any form he chooses", and can also transform others (who receive a −3 to their saving throws).

In actual Native American culture, Raven as a creator and trickster god was basically a thing of the Haida and Tlingit and other people of the Pacific Northwest. The art, too, looks vaguely inspired by those cultures, complete with a totem pole (also a thing specifically of the Pacific Northwest.).

COYOTE

"Hello, Fire Head Girl!"

Of course Coyote is here, as possibly the most famous figure from Native American mythology. The trickster Coyote comes from the traditions of Native American peoples of the Plains and Southwest regions, but of course that doesn't prevent him from being crammed in here into the same "pantheon" with Raven from the Pacific Northwest and, as we'll later see, other entities from elsewhere in North America. He's a chaotic neutral 14th-level cleric/14th-level druid/15th-level fighter/14th-level magic-user/17th-level illusionist/18th-level thief, and after this I think I'm going to stop giving the class breakdowns of the gods unless there's something really interesting about them because seriously, they're usually like this.

"Although Coyote is responsible for teaching arts, crafts, and the use of light and fire, he is primarily a bullying, greedy trickster." (Which I think actually is pretty much how he was portrayed in a lot of the Native American myths, so fair enough.) He can also change his shape, but not as well as Raven; he can only change into different animals. He's largely worshiped by thieves.

HASTSELTSI

We can't have a chapter about Native Americans without teepees somewhere.

And now we toss in a god specifically from Navajo mythology, because why not. Actually, as we'll see, although this chapter draws from traditions from all over North America, the Navajo in particular get disproportionate representation.

Also known as the "Red Lord", Hastseltsi is a god of racing who appears as a man with all red equipment. (Exactly what equipment isn't specified.) He also has a giant maroon horse that "is enchanted so it will run faster than anything it is competing against."

quote:

When he enters a tribal area it is because he desires to race, with any person and in any way. He never shows his godlike abilities (always running iust a little faster than his opponent).

Which... seems like it would make for kind of a pointless encounter. There's nothing that says that he places any wager on the race, or that there's any consequence for losing, so basically I guess the PCs are just beat in a race by some guy wearing a red loincloth or whatever his "red equipment" is, and they never find out who he was, and nothing ever comes of it. I mean, sure, a creative enough DM could find a way to make something interesting out of this, but it certainly doesn't immediately lend itself to much. (And that's assuming he does beat the PCs... for all the emphasis on his divine abilities, Hastseltsi, unlike his horse, is not said to be enchanted to run faster than anything he is competing against, and his speed is twice the speed of a normal human, which is fast, but not insurmountably so; in first-edition he can be easily outrun by an eleventh-level monk. Granted, he can fly at twice the speed he can run (so four times human running speed), but if he flies during a race that might sort of qualify as "show[ing] his godlike abilities". (And even then, he'll lose to an eleventh-level monk under a haste spell.))

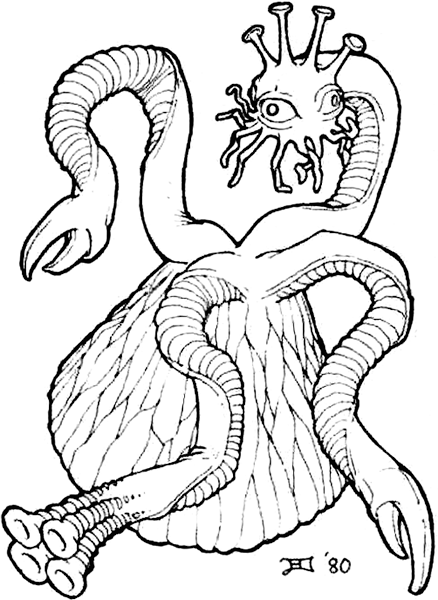

HASTSEZINI

I kind of like the stylized art that some of the gods from this pantheon are given. As we saw with Hastseltsi, not all the gods are drawn this way, but we'll see one or two more that are.

Also known as the "Black Lord", Hastsezini is a lawful evil god of fire who makes his home on the Elemental Plane of Fire. "This being is jet black and extremely ugly," and "is very fond of destroying villages by fire if they do not make sacrifices to him." Most of his description is about his combat abilities, which is odd, because how likely is it that PCs are going to enter into combat with him? Wouldn't it be more useful to give information about his worshipers, or heck, his relationship to other gods in the pantheon?

This is another Navajo god, by the way, as you may have guessed from the similarity of the name to Hastseltsi's. Which I'm sure never had the potential to cause any confusion in play at all.

HENG

Heng comes originally from the traditions of the Huron, a Native American people who lived north of the Great Lakes. Heng's header actually says "HENG (thunder spirit)", but he's listed as a lesser god, so apparently he really is a full-fledged divinity. "This god is favored among all the Indian tribes because he can sometimes be relied upon to bring rain to those that suffer, and give luck to those that hurt." But only sometimes, I guess. His priests "sprinkle large quantities on the ground to attract his attention" when they need rain, and then he may or may not choose to answer the summons. The guy's lawful good... one would think he'd be a little more conscientious.

Oh... Heng lives on the Elemental Plane of Air. No word on whether he and Raven are roomies.

We don't get an illustration for Heng, but since he just "appear[s] as a braided warrior of the tribe that summoned him", I guess we're not missing much. That doesn't mean, by the way, that he just appears as some generic warrior; he apparently copies the form of a specific warrior of the tribe, and the warrior he copies "will have luck in battle for the whole year (in the form of a + 2 to hit enemies)."

HIAWATHA

In his birch-canoe exulting / All alone went Hiawatha...

Hiawatha posted:

Possibly the greatest of all Indian heroes, this warrior can be found (with many other names) in many of the cultures of America. He is often depicted battling monsters and even gods on behalf of mankind.

Um... no, Hiawatha could not be found with many other names in many of the cultures of America. Hiawatha was not a mystical warrior who battled gods. Hiawatha was a real person. He was one of the founders of the Iroquois Confederacy, a semi-democratic union of several Native American nations that some scholars argue served as partial inspiration for the United States Constitution.

However, while the information here about Hiawatha is pretty much completely wrong, the authors of Deities & Demigods aren't the first ones to make that mistake. The Hiawatha in Deities & Demigods is almost certainly not based on the historical Hiawatha, but on the Hiawatha of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's famous poem The Song of Hiawatha, which had nothing to do with the historical Hiawatha either. Rather, Longfellow's poem was rooted in the stories of a figure from Algonquin folklore variously called Manabozho, Tcakabesh, Wisakedjak, or Glusakabe, among other names. Longfellow had originally planned on using the name Manabozho for the protagonist of his poem, but he somehow got the confused idea that Hiawatha was yet "another name for the same personage," as he wrote in a journal entry, and decided to use that name instead.

At least you could argue that the Deities & Demigods portrayal of Hiawatha is more respectful than Walt Disney's Little Hiawatha cartoon, I guess. I mean, would you rather be remembered as a lawful good druid/paladin/ranger who "transcends the normal boundaries of tribal feuds in that he will help all people in trouble", or as a clumsy young boy whose pants keep falling down?

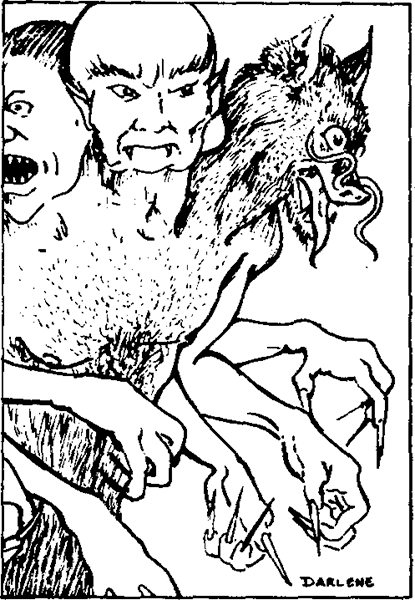

The text says Hiawatha "fought the great bear of death and won through hand-to-hand combat". So I guess that's what's happening here. We do not get statistics for the great bear of death.

HOTORU

A chaotic good wind god who casts lightning bolts in combat, Hotoru has a couple of things in common with Heng. First, despite his good alignment, he apparently only sometimes decides to help people out by giving them good weather or making their crops grow. Second, he doesn't have an illustration, but that's okay because he just takes the form of some nearby mortal anyway—though in his case it's "the form of the chief of any village that he is near", rather than a warrior of the tribe.

Despite these similarities in their presentations, Hotoru does not have the same origin as Heng—Hotoru comes from the traditions of the Pawnee, a Native American people from Oklahoma and its surroundings.

QAGWAAZ