Tales from the Loop by hyphz

If you hoop through the loop never loop it alone

Original SA postI was really surprised to see this hadn't been done yet, so hey.

1: If you hoop through the loop never loop it alone

The background

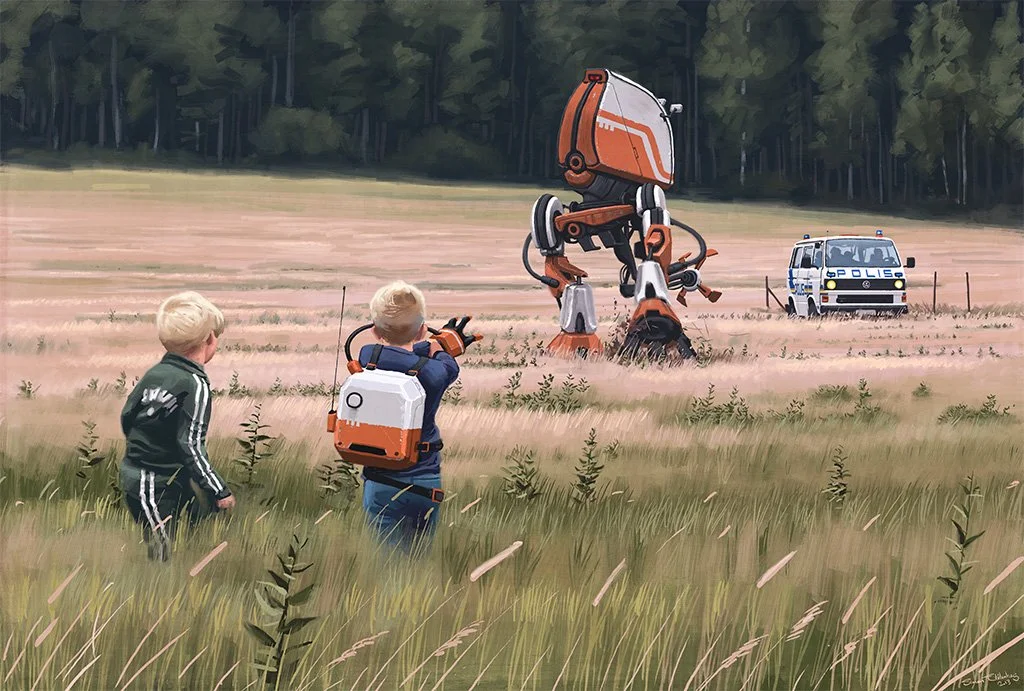

The first and important name in Tales From The Loop is Simon Stalenhag. The original inspiration for all of the related material is a series of his paintings juxtaposing childlike images of nature with technology that appears highly sophisticated yet has an old-fashioned appearance. You’ve probably seen them, but it’d be remiss not to include one, so here you go:

That’s The Remote Glove, probably the most used of the images, and also the one that inspired the banner image for the TV series (although the TV series changes the composition a bit to make it clear that the mech isn’t attacking the Police van). The earliest entry I could find related to his images was his website in 2012, which showed a number of artworks resembling the Tales from the Loop ones, albeit in a different style. It did contain a very small slice of what would later become the map of the Loop, although it wasn’t called that. It also listed his e-mail address at “futuregames.se”, which is a Stockholm-based computer game development studio, implying that the artwork was intended to be used in games - or to appeal to game developers - from the very beginning. The artwork recognisable from Tales From The Loop first appeared on his site in 2013, together with a reference to “Ripple Dot Zero”, a Flash based platform game which includes very Loop-style art in its backgrounds (although the majority of visible graphics in the game are simple platforms and pickups), and a piece of written fiction, “A day in the life of serviceperson Mikael Wirsen”, which seems to suggest a much greater focus on atomic energy than on an experimental particle accelerator.

Around 2014, Fria Lagan (aka Free League) published a Swedish compilation of Stalenhag’s art with the title “Out of the Echo Sphere” (“Ur Varselklotet”), which consisted of a collection of the images interspersed with short vignette-like stories about growing up as a child in the futuristic environment they portrayed. These stories introduced the idea of "Slingan" - "the Loop" - the experimental particle accelerator and research facility hidden below the landscape. The first Kickstarter for the project was launched in April 2015 and was for an English translation of the artbook, retitled “Tales From The Loop”. The RPG was a stretch goal on this artbook Kickstarter, and was only just reached before the end. The stretch goal promised only that it would be an RPG set in the universe of Stalenhag’s paintings; it didn’t state anything further about what type of RPG it would be or what theme it would have.

The artbook's textual vignettes themselves are mostly in the form of wistful recollections of childhood with sci-fi twists. A boy fools his friends by telling them that the daily horn warning for the flushing of the reactor cooling towers is actually a meltdown warning; a family grows up with a set of warnings taped to the fridge about the “Godel Pulses” produced by the Loop, and kids look forward to the strange momentary effects they produce; children come up with fantastic stories of having seen dinosaurs in the woods. The story associated with The Remote Glove is written from the view of the left-hand child who’s been going along with their friend while they snuck into an old building, found the glove and started messing with the robot, and then realised things were going too far when the police turned up. The final entry describes the decommissioning of the Loop occurring at the same time as the children grow into teenagers, making the real meaning plain: it’s presenting a view of childish fantasy from the view of a 80s child fascinated by science, who might fantasise about Loops below the ground more than secret coves at the bottom of the garden, and it’s not clear if any of it existed. In the book, the only “strange creatures” referred to as appearing due to the Loop are dinosaurs. Why? Because it’s a kid’s fantasies and kids think dinosaurs are cool. The pieces are well-written and charming, but most have very little in terms of a progressive narrative.

In July 2016, Stranger Things first aired - which was about teenagers investigating mysteries in a supernatural environment created by a scientific research facility. And in November 2016, the Tales For The Loop Kickstarter launched, and was about.. teenagers solving mysteries in an environment created by a scientific research facility. A thoroughly strange follow-up to the art book, which is specifically about children rather than teens, and has very little investigation involved. Yes, the children do explore and find things, but the focus is much more on the wonder created by the fact the mysteries existed. Yet the Kickstarter placed “in the vein of ET and Stranger Things” front-and-centre in the paragraph description of the RPG.

So, Fria Lagan had given themselves a surprisingly difficult task. Their sources were a series of paintings, obviously a visual medium, which they had to somehow fit into the primarily verbal experience of an RPG; and a series of vignettes covering exploration and discovery and wonder at the mysteries of the world, beautiful but not typically appealing to play, which they had to turn into the much more blunt and less emotional process of taking those mysteries and solving them so that all wonder in them is gone. Furthermore, Stranger Things focused heavily on the idea of a supernatural alternative world, whereas Stalenhag’s art was and writing had a strong scientific and technological focus (although one or two of the vignettes reference the supernatural, it isn’t at all common) - and unlike the later Tales From The Loop TV show, they didn’t have the option of using supernatural plots while using technological visual trappings, because visual trappings are much less effective in an RPG.

What’s even odder than the task is who they chose to take it on. When you think about Free League RPGs, there’s one name that comes up over and over: Tomas Harenstam. The original rules designer for Mutant, and highlighted as a designer on Forbidden Lands, ALIEN, and almost every other Free League RPG book.. but not Tales From The Loop. For Loop, Harenstam took the subsidiary role as editor, and handed over the design reins to Nils Hintze, whose previous credits were highly acclaimed articles in the Swedish RPG magazine Fenix, named Himlastorm and The Secret of the Faceted Eye. I couldn’t find what else he’d done, but it seems an unusual choice - although Loop is substantially more rules-light than any of Harenstam’s variants on the Mutant engine.

How did he do? Let’s see.

The Rules

Like Mutant, Loop’s stats are based on four stats with three governed skills each. Body contains Sneak, Force, and Move; Tech contains Tinker, Program and Calculate; Heart contains Contact, Charm, and Lead, and Mind contains Investigate, Comprehend, and Empathize. The separation of Mind from Tech is a bit awkward - it may be intended to represent the stereotype of the geek who’s incredibly smart with machine but nothing else; or it might just be that in the Loop setting, a single stat that combined abilities to investigate and use technology would be a god-stat.

The only other numeric values that characters have are their Age and their Luck. A character's Age is always between 10 and 15 - ultimately the game did end up focussing on children as the artbook did, rather than teenagers as the Kickstarter stated. A character’s age equals the number of points they have to spend on stats (not skills); their luck points are equal to their 15 minus their age. In other words, each year above ten trades one Luck point for one point in a stat.

Stats can range from 1-5, so the idea is that as a character grows up, they get more competent, but become less lucky. This works - as long as your players aren’t min-maxing. If they’re min-maxing, they’re going to want one stat right up to 5 out of the gate, which means that as their character ages they don’t get any better at it (they’ve already hit the cap) and may actually get worse (because they lose the luck points that they could spend to reroll the maxed-out stat). I’ll mention later how skill points work.

In addition to these, each character has an Iconic Item, a Problem, a Drive, a Pride, Relationships and an Anchor. Problem and Drive are purely narrative: Problem describes what will cause the PC trouble, and Drive is what encourages them to investigate mysteries. (The standard text in all of the sample plots for “what happens if the PCs just don’t want to engage” is “Remind the players of their Drives.”) The others have mechanical effects which we’ll see in a moment.

The dice system is simple. All rolls are Skill rolls. Add your stat and your skill, roll that number of d6, and you succeed if any of them is a 6. If you get more than one success, you can spend the extra successes on “bonus effects” specific to the Skill you rolled. If you get no successes, you can spend a Luck point (once) to reroll all your failures - unlike Mutant, failed dice that roll 1 are not “locked” in that state, and don’t cause attrition. You can also push your roll - again only once per roll - to get another reroll of your failures, but only at the cost of taking a damaging Condition.

Your iconic item gives +2 to anything you use it to help with; your Pride gives you an automatic success on anything that relates to it, once per session or adventure depending on your game pacing. This can turn a failed roll into a success, or add an extra success to an existing roll.

Loop doesn’t have Hit Points, nor does it apply damage to attribute values in the way Mutant does. Instead, there are four Conditions representing damage: Upset, Scared, Exhausted, and Injured. Each condition that you have applies a cumulative -1 penalty to all dice rolls. If you have to take a condition and all four are already taken, you’re Broken, which means you’re unable to go on or succeed at any rolls. An explicit rule is that Loop characters cannot die - they’re children, and if it comes to it they will always either escape or be rescued, although they might end up in trouble with their parents.

This has a curious relationship to Mutant’s damage system. The four conditions correspond directly to the the four “trauma types” in Mutant - Doubt, Confusion, Fatigue and Damage. In Mutant, these damage your individual attribute values; in Loop, they give a universal negative modifier, so they effectively damage all your skill values. In Mutant you're broken if a single attribute is dropped to zero; in Loop you need to run up all four conditions to do that, and if you take a condition you already have you have to mark a different one, so additional points in an attribute don’t give you extra defence. This means that Loop characters are actually substantially more fragile than Mutant ones, although they also have more options for succeeding on rolls. This might be intentional, to represent that they’re children, but Loop is also meant to be a far less hostile setting than Mutant, so who knows.

You can heal your conditions in two ways. You can go and hang out with your Anchor, which is the person you go to for comfort - usually a parent, but possibly a friend or other relative, although it can’t be another PC; or, go and hang out with another PC in your Hideout, which is the group’s choice of a home base for all of them. The GM is explicitly forbidden from introducing any danger when you do either of these, and NPCs will never find your Hideout unless you tell them where it is. So the system is much more heading towards PCs having to flee or escape when they are in danger than actually facing serious problems and death, which is quite fitting for the mood.

The other tricky thing about the system is the way difficulty is expressed. Mutant gives negative dice pool modifiers for difficulty; Loop requires multiple successes - up to 3 - although it does emphasise that this should only be used for the hardest tasks. Using your Pride still only gives one success, so it can’t give an automatic victory on a roll that requires more than one success, although it can boost a roll into a victory.

The game does provide a list of the probabilities of a single success on different numbers of dice. It doesn’t, however, provide that for multiple successes. Here’s the chart, listing the proportional penalty compared to one success in brackets. It doesn’t look good.

pre:

Successes Dice 1 2 3 1 17% Nil Nil 2 31% 3% (-91%) Nil 3 42% 7% (-84%) 1% (-98%) 4 52% 13% (-75%) 2% (-97%) 5 60% 19% (-69%) 4% (-94%) 6 66% 26% (-60%) 6% (-91%) 7 72% 33% (-55%) 10% (-87%) 8 76% 39% (-49%) 13% (-83%) 9 81% 46% (-44%) 18% (-78%) 10 84% 51% (-40%) 22% (-74%)

There’s very few further rolling rules, nor is there an explicit combat system. NPCs never roll dice, so there are no special opposed roll rules, apart from if two PCs want to roll against each other, in which case it’s most successes wins. What there is with regard to opposed rolls is a rule that allows NPCs to be given “special attributes” - which aren’t stats at all but arbitrary phrases with associated numbers - which specify that rolls against them where that special attribute applies require 2 or 3 successes. On the one hand, I like the idea that (as in the example) saying that a river has “Wild Currents 2” makes it plain that trying to put anything in the river or build a bridge is likely to be as problematic as swimming over it. On the other hand, it seems to allow potentially negative interactions, such as a door having “High Security 3” and therefore having that against any attempt the kids make to pass through it, no matter how inventive.

There is an an extended conflict system, where everyone gets to roll once and the total successes are pooled are compared to a target number which is a multiple of the number of players. As long as the group together get half of the successes needed, they can take conditions to buy successes directly instead of buying rerolls. Naturally, I had to try this out, although I could only do it by Monte Carlo analysis.

If we assume a group of munchkins with using maxed skills (3), on maxed stats (5), and using Iconic Items (2) for 10 dice, then most of the time they will succeed at a “normal” extended conflict (2 successes per player) almost all the time, by spending Luck points on the initial rolls. A “hard” extended conflict (3 successes per player) will again mostly succeed, but there’s a much higher risk of then taking 1-2 Conditions in order to do so. An “almost impossible” conflict (4 successes per player) is much nastier, with PCs (as a group) taking an average of 4 conditions in order to succeed.

But that’s with a perfectly minmaxed party. If we assume that not everyone has maxed skills, and that not everyone can use their single best skill in the conflict, then a slightly-above-average 6 dice per player is probably closer. At that point, even a “normal” challenge inflicts 1 condition, a “hard” one will inflict 4, and an “almost impossible one” will inflict 7 but with a 13.9% chance of failing to meet the initial threshold and being unable to succeed at all. And that’s with my system being quite generous and allowing people to decide to spend luck or push rolls after they’ve seen everyone else’s rolls, which has no basis in the book; without doing that, things would probably get much worse or more stressful for players.

Still, the goal of the extended conflict rules is pretty clear - to fill in for combat (Mutant doesn't have any extended rules, but it has a combat system) by creating a similar system which delivers a similar outcome, that is a fairly reliable victory for the PCs but with variable amounts of attrition. It has the common problem with such rules, which is that the abstraction involved makes the PCs actions - and especially the players’ decisions about what to do - feel much less relevant. But it’s probably necessary, as a full tactical combat system would completely kill the mood.

There’s also a section on what the skills do. I won’t summarise the whole thing, because in most cases it’s obvious, but there’s a few interesting things to note - especially in the “bought effects”, which you can trade successes for. First of all, almost all skills allow a bonus success to be used to give a success to another PC, creating teamwork. Second, several skills allow a bonus success to “avoid rolling to overcome the same Trouble in the future”; this includes Force - so it’s possible to beat someone up so well they just don’t bother you anymore. Most of the investigation skills work on the basis of asking the GM questions, and thus are very similar to the “Read the Situation” moves from PbtA games, only without partial successes.

There are only two skills which seem potentially problematic. The first is Move, which is noted as the skill most commonly used to dodge attacks, thus making it a nearly essential skill for everyone. To top it off, one of its bought effects is “No one notices you”, which potentially means that Move can stand in for Sneak - ok, the odds of getting an extra success aren’t always great, but no other skill subsumes another like that. The second is Lead. It has two effects: first of all, you can heal another PC’s condition without going to the hideout - that’s cool - but the second usage is that you can roll to lead the other PCs, creating a pool of 2-6 dice which other PCs can draw from only if they are following your instructions. This essentially gives a mechanical benefit for one of the players playing the quarterback, and potentially starts off the whole dumb argument about whether the players can discuss what to do and then have the leader PC tell them to do that, etc.

(By the way, the Lead skill is pretty useless in extended conflicts - it creates its dice pool rather than counting successes towards the target number, which means it trades one PC’s roll for an extra 2-4 dice.)

I haven’t mentioned yet how you get your skill levels. You get 10 points, but what you can spend them on is determined by your Type - yes, this game actually has character splats, although the distribution of skill points is almost the only thing it determines. Each type has three Key Skills, and you can put up to 3 points into those skills, and at most 1 into all of the others. Other than that, the types contain examples of Items, Problems, Drives, Prides and Anchors, but they’re only suggested values and there’s always the options to make your own.

The eight types are Bookworm, Computer Geek, Hick, Jock, Popular Kid, Rocker, Troublemaker and Weirdo. Each has a page devoted to their key skills and examples, and also each has an illustration. The only created illustrator is Stalenhag, so I don’t know if these are also by him. Here’s the Computer Geek:

(Any real Computer Geek would know that carrying a Vic20 around without its brick-weight power supply would be kind of futile.)

To avoid legal wrath, I’ll avoid listing the exact skill layout for every type. The majority of skills appear twice as Key Skills, except for Force and Move which appear three times (Force for the Hick, Jock and Troublemaker; Move for the Hick, Jock and Rocker), and Tinker and Program which appear once each (on the Hick and Computer Geek). Yes, you probably just noticed that the Hick, with Force, Move and Tinker, has potentially one of the best sets of Key Skills in the game. The two types who can Lead are the Popular Kid and the Troublemaker, potentially meaning that the “popular one” at the game table will end up playing the Popular Kid in the game too. They’re also pretty balanced in terms of stat dependence: almost every Type has two key skills connected to one stat, and the third connected to a different one - except for some reason the Popular Kid (whose skills all depend on Heart) and the Rocker (whose skills depend on three different stats, ouch)

Also, and unfortunately, one of the potential example Prides for the “Weirdo” is “I’m not heterosexual”. Yes, ok, I get that they’re saying that this is something a person can be proud of in the sense of not needing to hide, but saying it’s a person’s defining thing they’re proud of is not quite the same, and putting it on a character type called the weirdo is somewhat unfortunate. As is the possibility of a player having to decide which rolls they are able to claim an automatic success at because their character isn’t heterosexual.

That’s enough for now. Next time, we’ll look at the setting information and at the tips for creating Mysteries.