GMing advice books by hyphz

Robin's Laws - 1

Original SA postHi. I'm hyphz. I'm a bitter non-GM who annoys people by asking questions about improvisation. As such, I also have a tendency to collect GMing advice, and it struck me that actually examining published advice isn't too popular a topic in this thread (or any other).

And so, Ladies and Gentlemen, come with me to the year 2002, when the most recent version of D&D was 3.0e, OWoD was still current, and GURPS was still a thing you heard about. And if you asked about how to GM, well, someone would send you to..

Robin's Laws, by Robin D. Laws (I see what you did there), published in 2002, was for a long time the de facto standard for published GMing advice. It's still available from Steve Jackson Games' site as a scanned PDF, with an additional front page that - oddly - has the GURPS banner on it, and claims it to be a "electronically rebuilt copy of the last printed edition of Robin's Laws". Which I can tell you it isn't, because the scanned back cover has "first edition, first printing" on it, and my ancient physical copy has "first edition, second printing". Either way, it's definitely an artefact of its time. So let's jump in:

The first section, titled The Great, Immutable, Ironclad Law is probably what you'd think it is: Your goal as GM is to make your games as entertaining as possible.. That's a pretty good law, but it's also the ever-popular darling of bad teachers everywhere: the obvious, unexplained, dead positive. You might as well say it should be a good game is an ironclad law too.

However, there is some other interesting stuff in this section, which goes a long way to date the book. First of all, it states the designer's admission that only about 30% of the RPGing experience is ever accountable for by game design. This is a tricky one, because it's hard to say it's wrong, but if a designer believes it it potentially justifies them writing weak or incomplete systems (5e anyone?). Secondly, it states that roleplaying compared to regular media trades off polish and strong narrative properties for active participation, but then comments that "someday we'll probably find ourselves making regular terks to our local multiplexes to see movie versions of our favorite roleplaying properties.." Well, of course, that didn't happen except for the most popular ones, but podcasts did happen, and it'd be interesting to see how this section would be written in their light.

The second section, Knowing Your Players contains probably the most well-known, and enduring, part of the whole book: the list of player categories. You've probably heard these categories even if you've not heard anything else from Robin's Laws. The author actually credits "many of the categories" to Glen Blacow, a name I'd never heard before. A bit of Google revealed that this refers to an article written for the 1980 edition of RPG fanzine Different Worlds, titled Aspects of Adventure Gaming. Thing is, as the title implies, that wasn't a list of player categories; it was a list of "aspects" that could all be part of the experience in different degrees. Blacow only defined four aspects, while Laws defines seven categories. Furthermore, at the time Laws' list was more commonly compared to another list that appeared in Champions: Strike Force by Aaron Allston in 1988.

As with almost all category-based GMing advice, the book acknowledges that many players won't fit in just one category or in any categories at all, and that they're only vague grouping.. and then ignores that and fills the rest of the book with advice rigidly divided into those categories.

So, let's go. First of all, The Power Gamer. We all know what a power gamer is. They make a character to be as powerful as possible and play to gain more power. Blacow listed "power gaming" as an aspect too; oddly, Allston didn't, with his nearest equivalent referring to abusing the rules to min-max as much power as possible (which, to be fair, is pretty much what power gamers did in Champions). Unfortunately, he used an awful, horrible, inappropriate term to describe them: Rules Rapists, which is changed in most reprintings, but still seen on fora as late as 2018 and could get you banned from RPG.net in 2016.

Next up, The Butt Kicker. This is the guy, or gal, who just wants to fight. Now, how on Earth do we distinguish from the Power Gamer? Laws writes: "He may care enough about the rules to make his PC an optimal engine of destruction, or may be in different to them, so long as he gets to hit things." Could this be the mythical player type that inspired D&D 5e's Champion path? The problem is, in most systems if you don't care about the rules enough, you don't get to hit things; you miss them.

And the problem is pretty plain from that: the power gamer's definition is about having power, but the butt kicker's definition is about a particular way of using power, which requires you to have it. Nonetheless, these are treated as different and separate categories throughout the rest of the book. Blacow didn't consider this an aspect separate from power gaming or tactics (which we'll see later), and Allston divided it in two: the Combat Monster who enjoys fighting as part of the regular game, and the Mad Slasher who seeks to create violent mayhem by attacking out of turn. Whether the latter should just be dismissed as assholery is not really considered.

Next, the Specialist. The example of the Specialist is the player who always wants to be a ninja. Or a cat-person or a fairy princess or whatever (Laws' examples, by the way) They favor a particular character type, play it all the time, and want to get to do the cool thing that's associated with that archetype.

I don't like this definition. I don't like it at all. Why? Because I've played ninjas, I've played knights, I played a fairy princess the one time I could get away with it without being laughed at; and you can bet that when I was a ninja I wanted to be sneaky, when I was a knight I wanted to be strong and honourable, etc. Yet by the definition given here, because I don't play any single one of these character types all the time, I am not a Specialist and doing the cool thing associated with my archetype doesn't matter. If that seems pedantic, then consider what happens if you remove the "all the time" rule: you're left with the player who just wants to do the cool thing associated with their current character; and that category covers almost everyone! This is especially weird coming from Laws, who wrote Feng Shui, which specifically uses classic cool archetypes as classes.

Blacow never mentioned this category, and Allston spun it in several different directions: the Copier who copies characters from other media (again, showing the Champions bias there, since copying superheroes is almost de facto for that game), and the Pro From Dover who plays a character who is the best in the world at something. Allston also listed The Showoff who wants to show off their cool abilities, but suggested that they did this antisocially at the cost of other players' spotlight time, implying that this is another thing that shouldn't really be a category of anything except assholery.

The Tactician is our fourth category, and one of the oldest: Blacow listed the Wargaming aspect. The Tactician is the player who wants to plan and think and come up with involved solutions to problems, usually fighting ones; and as such, particularly values strong rules and an internally consistent world. The nearest Allston got to this was the Mad Thinker, who tries to solve problems, fighting or otherwise. Unfortunately, Robin's Laws shows a kind of suppressed disdain for the Tactician; they usually show up at one or other extreme of the recommendations and the advice for what to do is often in a more resigned tone. I don't know if this is the influence of Vampire or general frustration.

The Method Actor wants to get into their character's head and experiment with aspects of their personality. Blacow listed this as the "role-playing" aspect, and Allston divided this into several again: the Plumber who explores their backstory, the Romantic who focusses on interaction with other characters, and the Tragedian who wants bad stuff to happen to their character to see what happens.

The Method Actor is distinguished from the Storyteller; while the method actor is about exploring characters, the Storyteller is about the flow of events in the game, and making this have positive narrative properties and keeping the story moving. Blacow listed Storytelling as an aspect; Allston - very vaguely - divided it up (again) into the Builder who wants to change the world, and the Genre Fiend who wants to follow fictional tropes.

And finally, the last one, the one that actually makes me angry to read. The Casual Gamer. Look, I get what he's saying here. He's saying that some people just aren't necessarily that into gaming, or the current game, and trying to push them beyond their comfort zone is a bad thing. They're still valuable: they fill out background characters, provide an audience for those who needs them, and often act as social moderators who keep the gaming activity is perspective. That's cool. But then we get:

quote:

"You may think it's a bad thing that he sits there for much of the session thumbing through your latest purchases from the comic book store, but hey, that's what he wants. The last thing you want to do is to force him into a greater degree of participation than he's comfortable with. (Of course, if everyone in the group is sitting their reading your comic books, you've definitely got a problem...)

Ugh. That last sentence shows the problem: that there's no way of providing any distinction between the actual Casual Gamer, and the player who isn't involved in the game because they don't like it, but would like to be if it matched them better. The only way the author can give for distinguishing this is, apparently, numbers. Why can't you have a group of Casual Gamers? Well, apparently you can't. And the real problem is that throughout the rest of the book all the advice to do with the Casual Gamer is basically "don't worry about them, unless they start to show signs of greater participation". Which is carte blanche to, if someone's not into your game, just stick a Casual Gamer label on them and proceed to ignore them. Ugh. Allston called this type the Buddy, using a slightly better definition of the player who's there primarily because of friendship with the other players rather than the game.

The rest of the section is just suggestions on finding the individual motivations of the players in more detail (Laws calls them "emotional kicks"), and on spotting the types of new players. Some of these examples are telling: the Specialist is spotted by having created a character that matches a particular well-known type, without consideration of how often they create that character. And the Casual Gamer is spotted by, bleaugh, having been given a character friend by the friend who got them into the group, which makes them.. well, just a beginner, really, not someone who deserves to be disregarded in consideration of play style.

There's another odd omission here. It's mentioned multiple times throughout the book that the GM's enjoyment is as important as the players'; and yet there are no categorisations for the GM, nor do any of the tables based on those categories adapt to the GM's preference. I presume that's just because the author assumed the GM can sort out things for themselves, which is understandable, but then again they did buy a book of advice.

The second main chapter is Picking Your Rules Set, but it's not all that deep. It starts with a few fairly basic points about the need to adapt to the local popularity of gaming when picking a system, but to allow for your own enjoyment as well; and a section on Winning Converts which goes through the categories and talks about how each might feel about changing system. That's a fairly typical structure for the rest of the book. Power gamers resist change because they identify wit the cool powers; Butt-Kickers want it simple (apparently?) and prefer what's familiar; Tacticans don't mind as long as the new system has enough logic to puzzle out; Casual Gamers don't care about the rules as long as they're simple; and "Method actors and roleplayers" see the rules only as a necessary evil. Yea, he switched "storytellers" for "roleplayers" there for some reason.

This is followed by sections on the properties of game systems. Theme And Tone covers the style of games, although it tends to focus on the difference between power fantasies and the inverted powerlessness fantasies (in games like Cthulhu). Accessibility covers the game's support for stereotypes and recognizable imagery that can allow the players to quickly identify their interests. An especially interesting point here is a discussion of the interaction of local culture with expectations in RPGs. For example:

quote:

British audiences, on the other hand, view the power fantasy with greater suspicion. The English concept of heroism is less about victory than endurance in the face of seemingly impossible odds. U.K. game masters therefore can assume a greater license to make things rough on their players.

I've never seen any sign of this in the UK, to be honest, but my gaming group experience is limited. But the most popular games in the UK tend to parallel those in the US. Ditto, Laws writes:

quote:

Unique, highly distinctive settings dominate the French RPG market. North American audiences, on the other hand, will give up their beloved archetypes when you pry them from their cold, dead fingers.

I couldn't find that much about French RPGs in 2002, but the games I could find - which are basically the ones on Wikipedia: Agone, In Nomine, Malefices, Nephilim, Polaris and Reve de Dragon - all have the standard settings with twists on them, letting a player quickly latch onto something they want to play (a wizard!) but then adding a twist to it (hang on, I have to have a supernatural spirit crucified to my chest?).

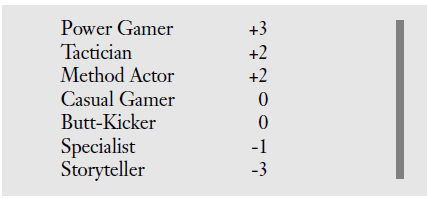

The final section, Power Balance, covers the well-known (and at the time well-believed, although it may be less so now) statement that "crunchy" RPGs favor the players, and "light" RPGs favor the GM. It then gives us one of several tables which lists the importance of crunchiness to each of the seven categories:

Average the players, and that gives a guideline on how crunchy your system should be. Yea, that.. doesn't really work. As written, a single Storyteller in a group tilts the entire system away from everyone else, among other things. Heck, by this logic if you have two exactly opposite players in a group they cancel out and everything is fine, which is totally the opposite of what would actually happen. Trying to reduce this to something as simple as an average is a bit of an unfortunate choice. There's an interesting sidebar, Homebrew Rules, which covers playtesting or modtesting and how the different categories react to it - but with a general warning that it's of more interest to the GM than the players.

Next up will be the sections on campaign and adventure design.

Robin's Laws - 2

Original SA post

I should mention, by the way, that the full version of that diagram shows a group of Indiana Jones-style explorers discovering.. a d12? Not entirely sure how a joke about die popularity relates to GMing, but there we go.

Campaign Design is our next section. It begins with a discussion of the benefits of planning the campaign in advance versus evolving it on the fly, which - just like so many other things - is divided up by the player categories. These are fairly predictable, except for one claim that was fairly common at this time and responsible for a ton of internet drama: that "storyteller" players "enjoy the grand sweep of a thoroughly-planned story". In other words, they're not story tellers but story hearers. This confusion isn't mentioned here, but it's recognizable as a mismatch that may have kicked off GNS and assorted theories.

Genre is likewise a fairly standard discussion on picking a genre based on player preference, but with the additional note that fantasy's popularity can be explained by the ability to fit almost any other genre into it. The Setting, however, is definitely another artefact of its time. It begins with a full page discussion of the wonders of published setting books, and the statement that you should use them, and should allow and encourage the players to read as many of them as possible, even "GM-only" ones, with the exception of prefab adventures. Why is this? There's actually a bunch of good justifications given:

- Players can watch movies, read books, read supplements, etc, over a period of years and start the game with that familiarity, rather than requiring a massive infodump at the start of the campaign.

- By the same logic, they'll have developed their own emotional assocations and reactions to parts of the setting which save you from having to stop the game at dramatic moments to explain the reactions their characters "ought to have" (imagine having to stop a Star Wars game to explain why the guy with the black mask and cloak is a big deal)

- Settings with big secrets tend to be incoherent or confusing without them, and ability for the players to engage with the setting is much more important than big surprise reveals - which are easy enough to work into any adventure anyway.

- Published settings have art, which the vast majority of home-grown ones won't.

- Most classic genres have published settings, so writing your own that matches one is just doing a ton of work only to throw away all the advantages above.

- This was published by Steve Jackson Games, who had over 100 setting supplements published for GURPS. Oh, wait, it doesn't list that in the book. Well, actually it does, just not in this section, but just hang on a moment..

These would all be good, except for the practical reality that most players don't actually read much setting material either. But certainly at that time there was a vague assumption that they did (thus the hundred setting supplements) so it probably makes sense.

There's then a section on Home-Brewed Settings which reiterates the line above. If your setting is too familiar, it's probably just duplicating a published one and costing you a ton of work. If your setting is too unmafiliar, the players won't be able to connect to it easily and you'll have to start depending on infodumps. The recommended solution is to just pick two existing genres and blend them, then check that they can be explained reasonably in a single sentence; or:

quote:

Blindfold yourself, take any two GURPS sourcebooks off the shelf at random, and combine the results.

There's also a sidebar section on Tone covering the broader scope of emotional tones in the games, which mentions that everyone tends to have a particular tonal habit that might be hard to break, and at least requires conscious effort to do so. There's also a rather curious admission that Laws didn't consider Feng Shui an innovative design, but a game with an unusual tone and "a few unusual pieces of GM advice".

Mission covers the broad scope of the PCs goal, whether it's a general ongoing theme (like "raid dungeons, kill monsters, and steal stuff") or a more specialized long-term goal ("restore the old Elvish empire"). There's a brief discussion of the balance between these two - the risk that a more specialized mission implicitly excludes a player's favorite activity or becomes too repetitive; the suggestion is that if you can't think up a dozen basic adventure concepts easily the mission probably needs to be wider. Finally, there's a section on Headquarters and Recurring Cast, which basically says it's important to give the PCs a base and recurring allies because otherwise a campaign can be ruined if the PCs suffer too much attrition and need to regroup; without an established way to do so, they may end up just fleeing from all plotlines unless they're saved by fiat.

The next section is Adventure Design. The first section, Plot Hook, covers the now well-known advice to make the goal of an adventure fairly straightforward and to not worry about making things too complicated. It does, however, give a much better expressed justification for this: that if the mission is to find out, say, who killed the Sultan, then as GM you know who killed the Sultan, but the players don't, and so for them the adventure includes all the possible killers, motives, methods and techniques of investigation already without them needing to be included in the plot hook.

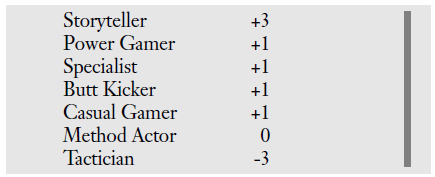

The next section, however, is another artefact of its time. Structuring Your Adventure. What's meant by "structure" here appears to be "story structure", as defined by a couple of properties: established action, building excitement, divided exposition, and varying rhythm and mood. There's then yet another one of those ghastly average-based tables for determining your "structure quotient", but this one is, well, just look at this:

Yea, just look at that spoilsport of a Tactician, ruining the structure that obviously everyone else wants. Keep that in mind when we go forward and we learn that structure may not be what you think it is, either.

And our first clue to that is: Dungeons and Other Unstructured Adventures. It essentially states that most players started with "plot-free" adventures such as dungeons, and if that's what the group enjoys, then just go with that - although it can be a bit boring for GMs and a bit unchallenging for players. There was similar text in GURPS itself as a justification for the superiority of adventures over dungeon crawls, and it totally misses a key point, one that anyone who's played BioShock knows (oh, wait, it's 2002, nobody ever has, Deus Ex then) - that a well-done dungeon or dungeon-like adventure can embed a narrative structure in its geography, possibly making the layout a bit weird but at the same time creating an easy way to manage structure without visible manipulation or railroading. This book doesn't even consider that technique.

So, let's see what the structures are. The first is Episodic. This is what most people now would call "a railroad", although "railroading" seems to be a term with mixed usage (it's sometimes apparently used to refer to just directing PC action badly). Guarding a caravan, or otherwise encountering a series of scenes with little or no influence on how they play out. It does, however, present some justifications to this: players have the flexibility to engage with or flee/skip encounters without fear for long term consequences; method actors can express their character's personality as they wish without knocking everything off the rails, and tacticians, power gamers and butt-kickers may not care all that much what the episodes are as long as they're fun battles. Which is fair enough, but unfortunately I then have to remember that Laws also wrote Four Bastards, an obviously episodically written Feng Shui prefab adventure that's probably the second worst prefab adventure I've ever read or owned (just for the record the first is Target: Mega-City One)

The second is Set-Piece. This is what Ron Edwards would later call Roads to Rome or Romeroading: there's a set of standard prepared events and the players transition between them, with the difference being that how the PCs get between them is much more open and there's more opportunity to change up what happens in the set-pieces, but they're still going to those items in that order. Oddly, there's no discussion of player types or preferences or otherwise for this, but that's possibly because of the next entry.

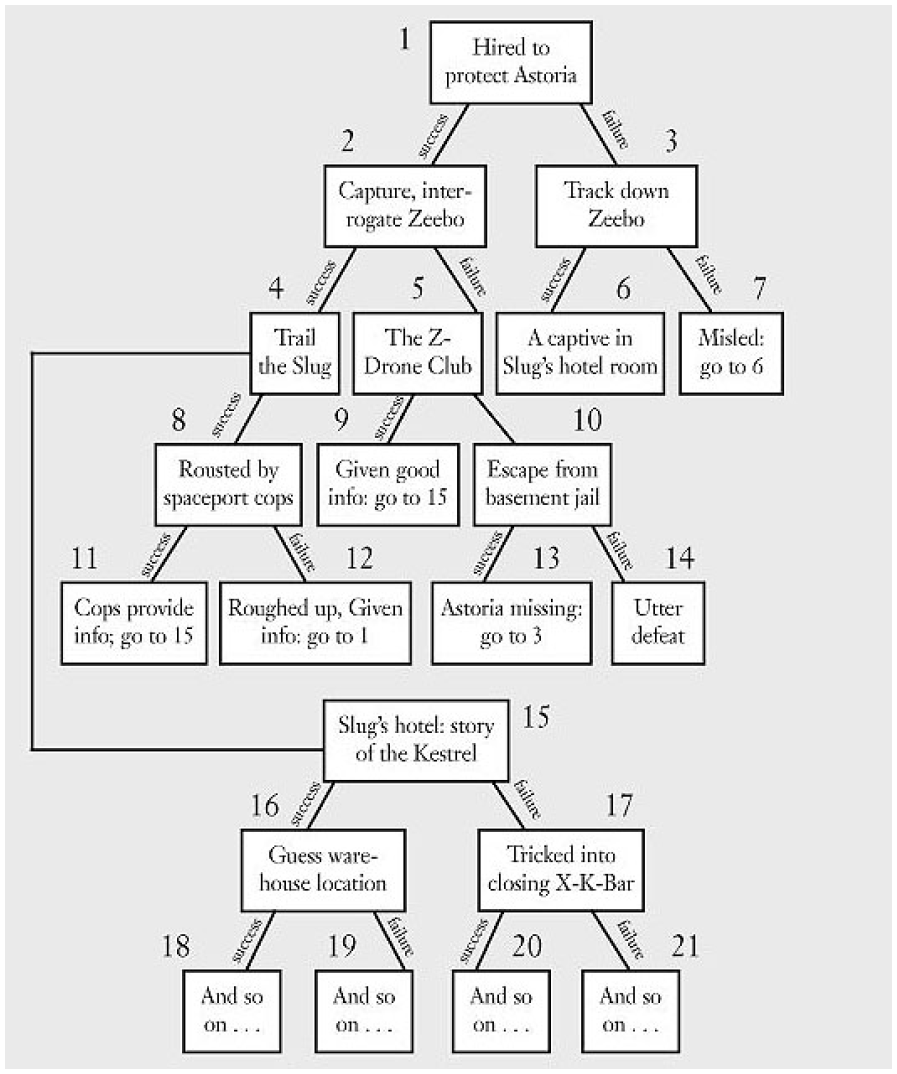

Branching is a very peculiar entry. First of all, here's the diagram that goes with it. The PDF makes this a full page diagram and states it was "previously only available as errata on the website", which isn't true, because my second printing print copy has it included in the text flow, and you can also see from below that it's been badly scaled up to fit on a page.

What makes this doubly unusual is that in spite of this diagram being there, the main focus on the section is saying not to try to do this. Essentially, the section states that actually having a structure like this is an unreasonable player expectation; what you're supposed to see from the diagram is how much material exists and isn't used, and how the diagram is incomplete. It seriously slams down any division between them:

quote:

If you're going to work out all of the scenes in advance, you're entitled to minimize the amount of work you must do by instead using the set-piece structure, where choices the players make determine how major sequences play out but not whether they occur at all. If the players want a greater number of possible storylines, they'll have to let you improve and accept the drawbacks of on-the-fly adventure creation.

Oddly, it doesn't state until the end of the book what those drawbacks actually are, but hey.

Enemy Timeline is another one that's only in the book so that you can be told not to use it, but at least it gets only one paragraph instead of a page and a diagram. It basically says "don't use rigid enemy timelines even if they're in your published adventures because the PCs will inevitably disrupt them and/or drop out of sync with them and ruin the structure". This seems to miss the option of the less rigid enemy timeline as seen in Monster of the Week, but that wasn't too common at the time.

But the last suggested structure, Puzzle Piece is an intruging one that I haven't seen described in these terms anywhere else. Essentially, it's very similar to the ideas of "standard NPCs" and "fronts" that pop up in modern games; you set a bunch of standard places and NPCs and events, and the players connect them together via their actions in whatever structure seems most appropriate for what they're doing. Unfortunately, the vast majority of the description of it is just a bullet-point list of the characters on the diagram, and the note "it gives you much greater when running the game, but requires that you know what to do with that flexibility". The book, sadly, isn't going to tell you.

The final section, Adventure Worksheet, essentially means going through the list of player types again and making sure that the adventure hits something that will satisfy each player's type and emotional kick

There's then another major chapter called Preparing To Be Spontaneous but I'm going to largely skip over it because it's really just an incredibly long-winded way of saying "make lists of stuff". NPC names, personality traits, lines of dialog, and so on. In fact, it focuses way too much on NPCs when they're initially only briefly mention as something you often have to create.

Next up are the sections on what actually happens at the table.

Robin's Laws - 3

Original SA post

Onto the final two sections now. Confidence, Mood, and Focus is our next major chapter, and the first to actually focuses on what happens at the table - although the book does say that this is much harder to analyze. Confidence doesn't even get a major header; it's just mentioned in the section forward that "you're doing a better job than you think". As pure emotional reassurance this would be meaningless in a book, but fortunately it's not presented as such; it's follewed with an explanation that players generally want you to succeed, and tend to be low-key even if they are enjoying themselves. Players who have also GMed know how difficult it can be and are probably sympathetic; players who don't GM tend to overestimate the difficulty too.

Mood is covered by sections called Reading The Room and Fun Injection! Stat. These, basically, say to pay attention to the mood of the players and react if things are becoming negative. If they are, throw in something based on the emotional kicks and player types that'll draw the largest number of players back into the game, even if it varies up the storyline of tha adventure to do so. Alternatively, it might be that people are just having a bad day or a conflict within the group, in which case it might be better to just end the session early. There's a single paragraph on Your Own Fun Quotient which basically says that the GM being bored will show through in the long run, but in the short run you should basically ignore it and focus on the players. Which is, well, rather awkward since it points out a problem without a solution, but hey.

The vast majority of the section is on the topic of Focus, which is essentially who is speaking at the moment - not quite the same as spotlight time, but certainly a similar idea - and what they're doing. And here we have something I don't recall seeing often anywhere else: an attempt to categorize, not player types, but actual time allocation between activities at the table. The categories given are:

Dialogue between PCs. By and large, this is a good thing to be focussing on; intervening as GM is generally not a good idea because doing so prevents the players becoming more comfortable with character dialog and advancing the group dynamics. The except is when it gets stuck in a loop, and the two most common loops are identified as related to tactics and morality. The author actually argues that the GM should straight up give OOC advice in order to break tactical deadlocks, whether it's reminding the players of the tone of the game that might not require massive tactical consideration (although big ouch there if you have Tactician players, which isn't addressed) or pointing out wrong or missing information. Moral impasses are harder, because they're the most common sign of a player who wants to define their character by a mismatch with the group; you can mark this as antisocial if you want, but it can add colour to play if it's done well. Unfortunately, the book's suggestion for this is to offer an alternative strategy that avoids the moral impasse, which might be difficult.

Dialog between PCs and NPCs. Again, usually good, but is problematic if it becomes repetetive or irrelevant to the main storyline. The recommended way to deal with this is to make sure most NPCs are in the middle of doing something when the PCs meet them, meaning that there's an implied time limit on the dialog and the NPC can potentially just leave any time the group is flagging.

Dice Rolling can be a problem in two circumstances: a) your group just aren't into it that much, in which case the author says you should avoid the rules codified aspects of the game (although "use a different system" would probably be worth considering at that point; mind you, in 2002 most systems followed the dice=combat rule pretty rigidly). b) is that your group are into it but it's getting boring, and the book makes a great point that this tends to be a natural occurance for many GMs, because when dice and combat come into play the GMs role becomes much more mechanical than it otherwise is; and, if there's a tactical subgame, the GM knows that they're probably "supposed" to lose, so they're more limited in tactical engagement than the players. The suggestions here are: if you're numbers heavy, imitate a bingo caller in calling and reacting to them. Descriptions of combat and the world are always good, and you can make a list of cool combat descriptions if you like; and finally, try adding unusual elements to fight scenes that the players and you can engage with (Laws would go on to make this an essential part of the Rune RPG).

Description and Exposition can cause boredom problems if either the GM has bad delivery (for which recording yourself is recommended, although it's mentioned it can be stressful) or the descriptions are too long and wordy, usually including too many minutiae.

Dialogue between NPCs, well, the author states most GMs know to avoid this anyway.

Bookkeeping, that is character building, shopping, etc, can actually be a positive and fun thing for some groups and player types, but can be problematic if it's unbalanced (one player is holding everyone else up) or slowing everything down. The only advice given here is to ask the player in question to do their bookkeeping before or after the session. Hope the system supports that.

Rules Arguments can actually be considered fun by some player types, especially power gamers. The solution offered is the well-known one - listen to the argument then make a quick ruling and move on, leaving any later argument for out-of-session - but it is also mentioned that you should go ahead and allow a well made rules point to derail any plans you had if necessary, because it shows respect for some of the categories that might enjoy this most.

Also, this section ends with the statement that a power gamer who can't argue about the rules might "look once more to in-character events to increase his overweening might". At first I thought "overweening" was a misspelling of "overwhelming", but it turns out it's a real word meaning "being too proud or confident in oneself". I'm not sure if that's a wrong spelling correction or a hidden sick burn on power gamers.

Disputes on GM calls. I'll just leave this here:

I really want to see some of those character sheets. Especially for The Hat and his super-speed ring.

Anyway, sadly this section doesn't have a lot to say other than ensuring that descriptions are clear (resorting to the use of props if necessary), and being prepared to rewind if there are genuine misunderstandings. This is probably 2002 striking again, since there's the implicit assumption that given full understanding there is an objective answer to every possible question like those above, which isn't the case in all situations and systems (although in 2002 it may have been seen as a goal of a rules system)

Digressions are a bad thing, and the only suggestion given for them is to delay the start of the game if necessary so that people can talk themselves out. Unfortunately, I can tell you right now that I've never known that to work. People stop talking when they see they are delaying the game, but then once it starts, feel free to digress internally because others are busy playing. Owell.

Dead Air is considered the worst of all, and the book makes the surprising step of blaming the GM exclusively for it - it's described as "when you stop the action to perform tasks". There's a few ways around listed, including better prep, doing extra last-minute prep during PC dialog, or just faking it. But there's no way of dealing with the awkward dead air when the players can't decide on actions or are doing similar things.

Finally, there's a short chapter on Improvisation, which is one I'd be particularly keen on - and the foreward for it does mention that many GMs find it intimidating. It's followed by offering an actual process for improvisational choices, which is this: imagine the most obvious result, the most challenging result, the most surprising result, and the result that would please the player most; pick one the feels best, consider the consequences to make sure it's not going to create problems down the road, and go with it. It's a pretty nice idea, but for me at least it doesn't help a lot with my own fears; in particular my nerves are always about getting stuck in a loop in the "consider the consequences" bit, either racking up dead air with rejected ideas or missing a consequence that I didn't think of at the right time.

This is followed by a section on Improvising Adventures which follows the common theme of assigning something to each player - in this case, a plot hook or agenda that they want to persue, and their Player Type which tells you what obstacles they're probably going to enjoy facing on the way. It's suggested that as a result, in an improvised game it can be a much better idea to "cut away" between PCs and allow them to potentially pursue different goals rather than trying to prepare an overarching run for all of them. This is followed by a section on pacing - although the first sentence is "how do you make a completely improvised session seem to have structure?" when pacing was only a small element of structure. It's then followed by "only storytellers really care that much about structure anyway" - after that chart which assigned "story structure" a positive value to everyone except Tacticans. Anyway, there's only one actual suggestion: "try to make the dramatic thing happen at the end of the session". The book does, fortunately, admit that this isn't always possible but it isn't necessary to hit it every time; the impliciation is that it's only a target to reach within sensible constraints, rather than allowing the wallclock to determine significant changes to the world, which is refreshing.

There's then a very brief section called A Final Word on the Ultimate Dilemma, which simply says "if players' preferences are disparate, you might have to negotiate with them or just abandon the group". Actually, a literal quote:

quote:

A fun game tries to balance the competing desires of its participants. To many folks, including those whose tastes are so pronounced that they've turned them into a philosophy of what gaming ought to be, this is not obvious at all.

I don't know which of those philosophies were actually around in 2002, but this probably stands up even better today. A brief section on If It Ain't Broke, Don't Fix It, then brings us to the end of the book (with ads for GURPS adventure and setting books, and Pyramid magazine).

So, Robin's Laws is an odd bird. Some parts of it are eternal, and some are very dated; and the obsession with categorizing players is perhaps a bit overbearing, although it was quite common at that time. What makes it remain interesting, though, is that it's really well written, and extremely well structured. It's actually pretty rare for a single author to write an entire book of GMing advice - most other GMing advice books are collections of essays or columns, which have their own problems, which we'll get to when we actually look at one - and to own that advice to the extent that Laws does here (ok, it's mainly a pun, but still he named it after himself, which is pretty remarkable when most other articles feel the need to insert "or maybe everything I say is wrong" disclaimers).

It helps that Laws is a good conversational writer to start with, and the editor was Steve Jackson himself. It also helps that the single author focus enabled the underlying messages of the book to be much more clearly expressed. Robin's doesn't have to have lengthy introduction paragraphs explaining the importance of adapting to your players, because it's literally what the whole book is about, and it includes justifications and reactions for most of its claims; a tutorial version of "show, don't tell". In fact, after Robin's, reading most other GMing books can feel like an exercise in frustration just because they're generally so badly organized compared to it. But, it seems we shall be doing so..

It's also worth mentioning that this wasn't Laws' last word on the subject, although his follow up was a bit stranger. Hamlet's Hit Points, published in 2010, describes itself as a GMing guide but is actually a guide to narrative analysis, focusing in particular on detailed analysis of three stories - with the argument that being conscious of this kind of thing will make storytelling and thus GMing better by osmosis, which is not necessarily wrong, but not necessarily what you wanted when you bought the book. (So much so that in 2018 he released a Beating The Story, an extension of the same techniques, but this time targetting authors.) I'm not going to go through Hamlet's Hit Points because it's mostly just literary analysis, but it's worth mentioning the forward which includes an interesting discussion of the involvement of narrative in RPGs and in the role of GMing, including things such as GNS. It also does reflect a bit of Laws' experience which may have made him a bit grumpy, as in the following footnote:

Never Unprepared - 1

Original SA postLet's continue our theme, with..

Now, I'm going to sigh at the moment. Because I'm getting hacked off. See, I've gone through a bunch of other books that are not Robin's Laws: and all of them have a bunch of problems which I'll summarise below.

Unnecessary padding. The amount of verbiage in many of these books is just insane. There are entire unnecessary chapters, and explanations of simple concepts multiple times. Several standard GMing books are actually collections of essays and the authors apparently didn't talk to each other, so there's a ton of repetition. Hey, do you know what an "offer" is in improv? Unframed will tell you.. four times. But that ties into..

Not knowing the level. For any teaching book you really want to know the background of your reader, and many of these books either don't consider that or don't allow for it at all. This especially applies to the essay collections, where an essay on your first session can be back-to-back with one on the merits of adding narrative contradiction to a plot. And finally,

Not knowing how to teach. A GMing book can't be a technical reference or walkthrough book like an RPG book can be. It has to be actually written to teach, and that's not easy. There's a reason there's a flood of god-awful self-published textbooks.

So, Never Unprepared - one of a series of three books by Engine Publishing, the others being Odyssey and Focal Point - tries to be a tutorial on how to prepare for sessions. And good grief, it's a slog. I don't like copying and pasting text, but seriously, just look at this stuff from the first two chapters.

quote:

When you say “session prep” to most GMs, they imagine a pile of handwritten notes spread across a table; a kudzu of loose-leaf and ink attempting to consume any free space it can find. They have blood-chilling visions of sitting at a desk like a monk penning a copy of the Bible, writing endlessly in silence. They have flashbacks of high school and college term papers, pulling all-nighters to get them finished in time, and the fatigue and the low-level self-loathing that comes from making yourself stay up all night for nothing more than homework.

Wordcount padding technique one: unnecessary examples or metaphors for things that the reader already understands. Pretty much nobody is buying a pure GM advice book before GMing their first session. If the reader doesn't understand this, what's the point of teaching them a negative image of prep that allegedly other GMs have, just to try to tell them it's wrong?

quote:

Session preparation is the act of preparing oneself as the GM for an upcoming session where you will run a game for your players. Session preparation (which I will call prep from now on) is related to campaign preparation, which is the act of organizing information for a campaign, or series of sessions. This book addresses session prep, but some of the concepts presented are applicable to campaign prep as well.

Thank you for telling us that preparation is the act of preparing; that being a GM involved running a game for players; and that prep is short for preparation, and for taking 71 words to do it.

We do take a brief moment to say something useful, in terms of the benefits of prep in terms of types of stories that have problems when run improvisationally, such as mysteries; and the fact that many GMs do not like prep but this may be because they are doing it wrong.

quote:

Every GM, experienced or new, has been in this situation: on the spot, facing your players, when something unexpected has

happened in the game and you are searching for what to do next. It could be that the players have attacked the king, or the party has decided to explore the hex to the west and not the one to the north, or the mage attempted to bluff the villain into revealing his master plan and succeeded.

Drink for wordy, unnecessary examples.

quote:

GMing is in many ways like radio, where silence is death. When I was in college I was a DJ at the college station, rocking out metal at 10:00 in the morning. The first lesson they teach you is that having dead air is the worst thing that you can do. If someone is listening to your station and the song ends, and another song does not start right away, people reach for the dial and move to the next station. You’re taught to do anything to avoid that silence, from timing your songs so that one flows into the next, to jumping on the mic and jabbering away until you can get the next song going.

GMing is no different: Silence is death. When a session is in full swing and you are narrating the scene, judging the players’ actions, and playing the roles of the NPCs, your players are hopefully following you. When this is running at its best, there are moments when the walls of the gaming space melt away, when you see your players as their characters and they see your narrative as the world around them. In those moments you have reached true immersion, the zone of RPGs. When you reach that zone, you want to stay there as long as possible; those are the moments that we all—players and GMs alike—remember for years to come.

The last thing you want to do in one of those moments is to fall silent because you’re unprepared.

Silence is bad. Got it. Now seriously, let me rewrite this in like 5 minutes:

Every GM, experienced or new, has been in this situation: something unexpected has happened in the game, they have to search for what to do next, and while they are doing so the table goes silent. During that silence, immersion breaks and the table slowly devolves into building dice towers and sidebar conversation. The longer the silence goes on, the harder it will be to recover that immersed state. The more prepared you are, the less often those moments of silence will occur in your game, and the better your chances are of reaching that immersive state.

That is 97 words. This book? Takes 502 to say the same thing.

We now get to a more useful statement: that ideally, prep should be accessible, organized, effective, and reliable. While true, this means that the author has now switched to using "prep" to mean the result of prep, not the activity, which would be more forgivable if he hadn't defined it like 3 times by now.

quote:

What I just described are the high-level requirements for any database system from a recipe app on your smart phone to the most complex banking servers.

Another unnecessarily comparison. Anyone who knows about database design knows this. Anyone who doesn't will get nothing from the metaphor.

quote:

The First Rule of Prep Is: We Do Not Talk about Prep

Which is the header of a section on how we absolutely should talk about prep rather than leaving it as the elephant in the room, which is a damn good point, but hey. Who cares if we have a header that means the exact opposite of the underlying text, if we can work in a Fight Club reference?

quote:

My own style of prep was conceived largely without input from other GMs. Some of the tools I use were suggested by friends, but the contents of my notes, and the system I use to plan the time to write them each week, were discovered by trial and error—a lot of errors. Over the years I evolved a style of prep that I became comfortable with, but I never really understood why it worked. I just stuck to it because it did.

When I became a father, something wonderful happened: Being a dad is insanely awesome. Something terrible happened as well: My free time vanished. Suddenly my tried-and-true approach to prep was falling victim to a massive time crunch. With no real resources to draw upon, I started to work at my prep and find ways to make it fit into my new, much tighter, schedule. Along the way I learned some valuable lessons.

You are great. Now tell us stuff.

The next section attempts to address the common errors that GMs make when preparing. The first one of these is writing too much. The irony is palpable.

quote:

This is the most common reason that GMs dislike prep: They are simply writing too many notes. They often do this because when they first learned to play, they took copious notes to make sure they were well-prepared for their sessions. Over the years they have grown as GMs and their skill at handling the game on the fly has improved, but they are still writing volumes of notes.

A common question that I’m asked when I am on GMing panels at conventions is “How long should my notes be for a session?” My answer for this is always the same: As long as you need them to be to comfortably run your game. Less experienced GMs often need more (and more detailed) notes because it makes them feel comfortable GMing. More experienced GMs often require fewer notes because they fill in the gaps with their improvisational skills. What GMs often fail to do is to review their skills and attempt to trim down their notes as they grow in experience.

Gaaaaaah! Ok, not only is this wordy (why does it matter where the author gets asked that question?) but it's a fundamental error in any tutorial. Obviously, if the reader is writing too many notes, then their belief about how long they need them to be is incorrect. Telling them to fall back on that belief is not teaching them anything. The final sentence, about reviewing skills, has a point. Ok. So, how do we do this review? Dunno. There's nothing about it in the book. There are skill reviews, but they're to do with the prep skills the book presents, not the underlying GM.

Second reason: prep can be found boring because you are using the wrong tools. Now, damn, I'd love it if there was a sufficiently inspiring semantic system to make prep for every system fun. I've even just found it fun to transcribe bits of the Spire setting into Realm Works and that's by no means an ideal tool. But unfortunately, you don't always get to choose. Although hey, if anyone wants to try to write a prep tool together, I'm up for that.

Third reason: you either don't leave enough prep time, or try to prep at times when your creativity isn't great. Again, it's a fair point, but you don't always get to choose, given that preparing an RPG is not going to be a high priority compared to most other activities for an adult.

Now we move on to "The Phases Of Prep".

quote:

A common misconception is that prep is the thing you do when you write your notes or draw the maps for your upcoming game.

Actually, that's exactly what you just did when you referred to prep as a database.

There's then a section called "How This Came About", which describes how the author wrote the chapter. Nobody cares. The only time this stuff is useful in teaching is if it gives a concrete example of the teacher's experience in doing the thing being taught, and this book isn't about how to write GMing books. Moving on.

What this chapter eventually gets to is to break the prep process down into five steps: Brainstorming, Selection, Conceptualization, Documentation and Review. We then have an overview of these five, before a chapter covering each. Technically this overview shouldn't be necessary, but anything to add to the page count, I guess.

Brainstorming is having ideas. The section reminds us that ideas are incomplete and that it can happen almost anywhere. We spend 35 words on how important the ability to have ideas is in the advertising industry.

Selection is choosing which of them are good ideas in terms of quality and fitting into the tone and world of the game. This makes sense. Ok.

Conceptualization is actually fitting the idea into the game in terms of the world, the need to make sense, and the game mechanics. That makes sense too. Cool.

Documentation is writing up the results, which is commonly thought to be the whole of prep. We spend 78 words explaining different ways in which to write and store your documentation, because we needed to know that it's possible to hand write documentation and put it in a binder.

And finally Review, which is reading through the documentation to make sure that it passes muster, and getting into the mindset of being ready to run the material.

There's then a bit of reassurance that this is just a summary of a natural process, and that it doesn't represent a ton more preparation work (which, you will recall from the last chapter, we are doing too much of and do not enjoy).

Next time, we'll get into the actual chapters, but I hope this has shown some of the issues I have with this and many other such books I've slated to review in this theme. It might mean that things get decidedly shorter later on.

Never Unprepared - 2

Original SA post

So, we now get onto the actual chapters covering the steps of prep. These are somewhat better than the overview chapters were, in that they do actually contain some reasonably organized content. Unfortunately, they still contain a ton of extra verbiage. The first paragraph on Brainstorming, for example, is a list of florid metaphors for ideas.

Cutting through the cackle, Brainstorming means starting from a question, seeing what ideas it inspires, and writing them down. There's intended to be no selection of ideas at this stage, and here we get the first piece of really good advice: not rejecting ideas for smaller scenes because you're trying to think of a Big Idea for the session. There's also a good list of inspiration questions; the default is "what should I do in the next session?" (I might switch that to 'we do' but hey), and others include "what did the players want to do?" "what would the major NPC be doing right now?" "is there an event that's due to occur?" Brainstorming is best done in a quiet room when you're starting, but as you get more experienced it can be done anywhere, and oh god he's actually listing brand advertisments for notebooks and note-taking software, pull up!

Signs of too little brainstorming are feeling that the well is dry when it comes to developing ideas, or retreating to safe and established ideas or those lifted from other media. This makes sense as a statement, but I'm not quite sure of its accuracy, given that "ideas lifted from media" is a pretty comprehensive set by now (please refer to the "Simpsons Did It" episode of South Park). Doing too much brainstorming is unlikely, but usually means that ideas are being forgotten or not fully exploited. There's then a section on how to improve, but it doesn't say much except "practice" - although that's kind of inevitable with a topic like this - and then reiterate for the third time that you can brainstorm anywhere.

The section ends, as all the section do, with two scales to "rate your frequency and skill level" at performing the task the chapter is about. Ideally the two scores should be similar and as high as possible, but in practice there's usually only like a single vague sentence about what to do with the score once it's calculated, so it's mostly just a pointless mental exercise.

Selection is about picking from the list of ideas, and oddly is framed as picking one to be the basis of the session (rather than just filtering multiple ones to use). Four perspectives are listed to consider: the players, the GM, the game (system), and the campaign.

Players is considered only in terms of whether or not the players will enjoy what the idea will have them doing in the moment (not what it leads to, which makes a certain amount of sense). The author cites Robin's Laws for player categories, and then lists three aspects of play - Roleplaying, Combat, and Problem Solving - perhaps unaware that he's actually leapfrogged Robin's there and jumped right back to Blacow's 1980 article that Laws cited, except that Vecchione's list conflates Roleplaying and Storytelling together, replaces Wargaming with Combat, removes Power Gaming, and adds Problem Solving. I suspect that Blacow's list would have considered problem solving to be a "wargaming" activity, but honestly this just shows a lot of problems with these definitions, since wargaming is not necessary combat (tactical solving can apply to other things) and combat is not necessarily wargaming (see any game with a more drama-focussed combat system)

"The GM" as a consideration is about what you, as GM, prefer to do. What do you prefer to run? Do you give a lot of detail, act out NPCs gregariously? Do you prefer to present challenges to be overcome or collaborate with them? Are you good at managing a lot of things? They're all good considerations, but they're not given a great deal of detail beyond asking the question. Also to the author's credit, there is a paragraph on how you shouldn't necessarily let your pre-existing beliefs about what you like or are good at define all your future games, and that you should prepare in the areas you're weaker in, which is good. It does, however, then say that this is best avoided at the start of a campaign when you are "laying the foundations".. which I'm not too sure about, because it potentially inflicts a bait-and-switch on the players.

"The Game System" is a similar section, in that it mostly consists of a list of questions to ask about your game system, but unfortunately in this case they're much weaker, mostly focussing on what the system has rules for (rather than, for example, what it does well); and the text is heavily padded with questions of the form "does it have [incredibly specific thing]" (with the set in question being aerial combat, a sanity system, mass combat, and kingdom building?). The example is awkward, too: it suggests that if you want to run a treaty negotiation, then AD&D 2e would have no rules for such, and D&D 3e might be a better choice because it offers skill support. But that skill support, as any OSR player will tell you, is not necessarily a good thing: it's just one skill, and you then have to deal with questions about what's covered by a single roll, how actions modify the roll, what role-playing is required to justify the skill roll's usage, and so on and on and on..

And finally, The Campaign is, does the idea fit into your campaign. But alas, there is no discussion of continuity or anything similar here! Literally the only example is that space aliens probably wouldn't show up in a fantasy game (unless it's Expedition to the Barrier Peaks).

Too little selection, and you invest too much in ideas your players won't like, your system won't support, or that you can't run, and lose interest. Too little consideration of selection, and you end up running a game just for yourself rather than the people you're playing with. Too much selection traps you in your comfort zone and also delays everything else, meaning that later prep phases are weaker. That's an excellent point, but unfortunately, there's no clear guidance on getting over that. The only "improvement" section here is about introspection and establishing exactly what your filter should be, which is a good point, but not for that aspect.

Conceptualization is probably the weakest section so far, as it's where things seem to start to fall apart. Essentially, the author describes the process of considering an idea from brainstorming and expanding it into a story. There's a bunch of lists on the standard questions to ask (Who, What, When, Where, Why, How), some story integration prompts, and on the rising action structure of a story.

Unfortunately, there's no allowance whatsoever for anything but taking one brainstormed idea and converting it into a story - there's nothing mentioned about combining multiple ones together. Also, there's nothing about what to do if you don't want to write a story in advance - there's a sort of statement that it shouldn't imply the players have no choice, but not really anything about how to structure things so that they do, or how to "conceptualize" anything other than a story (there's a very short section on a scene, but nothing else).

Too little conceptualization, and one of three things happen: plot holes destroy the flow of a session, lower level aspects of play become boring because they haven't been looked at enough, or documentation becomes garbled because it was written too soon. Too much and you spend time preparing a ton of material the players won't use.. but unfortunately, the only advice given on this is to try to predict the player's actions better. Again, the methods for improvement aren't particularly insightful, and unfortunately the section go in circles just advises iterating conceptualization as a method for improving (whereas, for example, my problem here is iterating it infinitely until it becomes unresolvable) It's also notable that in the earlier overview, Vecchione mentioned that it might be necessary to throw out ideas at the conceptualization stage, but that's never actually mentioned here.

Documentation is probably the most pointless section so far. It basically says, you have to do a bunch of things during the game, make notes that you're comfortable with about the things that you need them for. Try different ways of note-taking, and try doing conceptualization first.. but at the same time don't be afraid to go back to conceptualization if you realise something's missing while you're writing up. Ugh.

Too little documentation and either you forget things or.. well, ok, here's a nice controversial quote: "There will be times when [your players] do the unexpected.. if you don't have a written version of the adventure on hand, then you're much more likely to be at a loss about how to move forward." That's.. well, pretty much the opposite of most things I've heard on that topic. There's also a section on how having notes makes it less likely that you'll lose important rules, but that actually turns out to be telling you that it's a good idea to look up rules based on what you think is going to happen, which is true but not really in the base category of "too little documentation".

Too much documentation either causes railroading as the "missed" documentation is forced to be used; or, more likely, kicks off a death spiral where the GM never believes their notes are adequate no matter how much time they spend writing them, and ends up losing interest in running the game because they always feel they should have done more beforehand. I can definitely relate to that. Shame there's nothing here about it other than "don't over-document" which falls into the exact same fallacy this did in the overview: nobody in this position thinks they themselves are over-documenting.

Review is checking everything over. This is divided into three categories. Proofreading is checking for grammar and spelling errors (in notes just to yourself? Well, maybe, I suppose), but more importantly rules errors. Director Review is checking that the story will flow properly, there's no plot holes, and that the bits that are supposed to be dramatic will be. And finally, Playtester Review is checking that things will work when actually played. Too little review, and things become disorganized and stumbling, have errors, or are blindsided by players. On the other hand, too much review means.. that you question things too much and are full of doubt when you reach the table. What's the right amount, then? As usual, no attempt to define this.

Also, this section several times refers to the GM's "psychic RAM". You're allowed to just say "memory", guys.

Chapter 8 is Tools for Prep but.. it's more or less just more filler. Use a notebook or a wordprocessor or whatever makes you comfortable, switch tools if you need to, get used to using the ones you pick. The book's third name-drop of OneNote. The book's first name-drop of Getting Things Done, the infamous management guide to complex to-do lists. And the author's bizarre description of themselves as "an office supply geek".

Likewise, the chapter on Mastering Your Creative Cycle is actually just a bunch of cookie-cutter time-management tips about drawing up a weekly schedule to identify how much free time you have (for doing prep, of course) and identifying times when you're feeling more creative. Probably the only really interesting bit is a chart of which prep activities need more creative inspiration, in order that you can divide them between times; but let's face it, time to prep a game probably isn't something you're engaging in a complex organizational framework in order to obtain.

Your Personal Prep Template encourages customizing the steps above for what's appropriate to you, which is good, but in practice repeats a whole ton of material from earlier, including the definition of prep (fourth time, now), and adapting to the GM, game system and campaign. There is a bit of useful stuff here, such as different things you can do to cover weaknesses in GMing (although predictably enough, they all come down to "prep that thing") and what fields to include in a template if you decide to build one.

Chapter 11, The Prep-Lite Approach starts off by sounding like it's introducing a whole new technique (or "philosophy", as he calls it), but it quickly turns out not to be. Instead, it's four principles for reducing prep if you feel that the need to do it is reducing your ability to run games, but two of them are duplicates: focussing on playing to your strengths, and covering your weaknesses. The third and fourth are "They can't see your prep" and "Abstract mechanical elements", and basically come down to "fudge it". Steal maps and ideas from elsewhere, reskin NPCs basically on the fly, and use standard simplified values instead of fully engaging with mechanics. You know, all those things that were actually described as failure conditions earlier in the book.

Prep In The Real World is.. oddly, a chapter about risk management and how it affects prep. This will come up in other Engine Publishing books as well, and is a bit of a sign that Vecchione is copying material from standard business management strategies and rewriting it in gaming terms. (That's because, as mentioned on his bio, he's actually trained as a project manager and did a chunk of that work for Gnome Stew, too.) What do you do if you get sick? If something comes up abruptly? If you just don't feel creative enough to proceed? If there's a sudden plotting catastrope (the book calls it Hard To Starboard) what should you do? Uh, try your best to fix it and remanage your time if you can. That's basically all. Huh.

And the Conclusion is just authorial background and a "thank you".

The list of References and Inspirations at the back of the book does however confirm some of our earlier positions. They cite Getting Things Done and the other stuff from David Allen (yea, he loves this guy. In fact "Allen, David" is the first entry in the index with six references, inspite of the fact that nobody's likely to be looking up his name), Lifehacker, Time Management for Creative People and The War of Art - all fairly generic management books with no particular relevance to gaming, but generic enough that they don't really need it added in. Also cited is the author's own writing on Gnome Stew, which oddly includes a number of statements about the "Prep-Lite" method - "wireframes" and "skins" - that were never actually mentioned in that chapter.

Never Unprepared is.. well, it's not awful. But it's not even close to Robin's Laws in terms of information level, with almost the entire foreward and a number of the later chapters either relatively obvious or just straight up duplication. The same thing actually happens in all of the Engine books, Focal Point possibly being even worse, although Odyssey does a much better job of avoiding it because of its wider scope. The Brainstorming and Selection steps are a pretty good idea, if not exactly earth-shattering revelations, but from Conceptualization forward a whole bunch of assumptions are made about the structure of the game or system used, that don't necessarily fit in with all systems, especially not more recent ones.

Basically, it's a common problem: anyone who could really learn a lot from Never Unprepared probably wouldn't buy it. It'd be stuff that'd go well in a starter RPG if it could avoid bloating the page count too much, but it won't have a huge lot of interest from someone who's been involved long enough to want to make a conscious decision to improve GMing. It's not a bad try, but ultimately it's a swing and a miss.

I did, however, look up Gnome Stew - the site which is connected to Engine Publishing multiple times in the book. It turns out it's a group blog, which might explain the rather bumpy comparison to writing learning texts. There's a "top 30 game mastering articles" on the site, but the author of Never Unprepared (under the name DNAPhil on that site) has only three of them; only one of them is vaguely about prep; and it's actually about not prepping the ending of a campaign - something which was implicitly advised against above if you intend that the ending would be dramatic. To add even further irony, in Focal Point - two books down from Never Unprepared, and written three years later - the same author writes that he hardly does any prep and usually only writes a page or two.

There's one last thing. Any goons interested in actually trying to write a better guide to GMing? I know that Fuego is setting up a new wiki for TG, which could be a good workspace for such a thing. I'm only floating it as an idea because for obvious reasons I wouldn't be able to contribute much myself!

D&D and HoL

Original SA post The GMing advice from that one game..It's difficult to write reviews of this kind of material without considering the GMing material that actually appears inside the games themselves. However, as PurpleXVI said, most GMing advice in actual RPGs is kind of generic. Nonetheless, it would be remiss to ignore it completely, so let's consider what, by rights, should be the most influential GMing advice in the world.

A Twitter user called Talen Lee referred to "why don't you just not play D&D" as the "just use Linux" response of tabletop gaming, which got 35 likes. The metaphor is apt in a whole bunch of ways. Just like Windows, D&D is limited in its amount of innovation by its userbase's addiction to older material; used by many willingly, and many more because the trust that software/players are available now and will be available in the future is an overwhelming tradeoff against any number of other failings; and while you don't have to like it, you can't ignore it. So I'm not going to.

I say "by rights" above, because I doubt very much the GMing advice in this book is actually the most influential or indeed that influential at all. Very few people I know who play D&D have ever read even the D&D Players' Handbook from cover to cover, and many of the GMs I know have never even opened the Dungeon Master's Guide at all except to refer to magic item descriptions when running published adventures. (I've seen GMs be totally gobsmacked at certain optional rules existing in the DMG.) But maybe, at some point, someone might have read it for what it says about DMing? Who knows.

One thing I do want to make clear is that I am not going to review the entire Dungeon Master's Guide. It has a ton of game specific rules which I'm not looking at. It also has a fair bit of material on world-building, which I've deemed out of scope for these write-ups since it's a whole separate theme that's shared with fiction. But there is, nonetheless, some agnostic stuff in there.

For example, I was as surprised as many of the GMs I described above to learn that D&D 5e has a player categorization scheme.

Well, ok. It's actually an "aspects of play" scheme like Blacow's was. But a little more digging reveals that it's almost entirely copied from a player categorization scheme that appeared in the Dungeon Master's Guide 2 for Fourth edition - which was in turn based on one that appeared in the DMG2 for 3.5 edition. 3.5e gave each one a couple of paragraphs; 4e gave them even more paragraphs with headers, including some odd things such as where they should best be seated at the table; and they're massively shortened down to single paragraphs and bullet points in 5e. But I can't necessarily blame them for that, given that a Dungeon Master's Guide 2 is a rather niche supplement while a core DMG has to contain a ton of rules, items, and so on. (That said, there was more DMing advice in the Fourth edition Dungeon Master's Guide than there is in the fifth edition one, too.)

It's also worth noting that Robin Laws was a cover credited author on the Dungeon Master's Guide 2 for both 3.5 and 4th editions, which explains that, at least in their form in 3.5e, the categories are almost the same as his original ones from Robin's Laws - especially not surprising given that the DMG3 for 3.5 was only three years after Robin's. 4e also has several quoted paragraphs from James Wyatt's Dungeon Master 4th Edition For Dummies, a book I don't have, but that apparently used the same categories because they're specifically mentioned in the quotes. 3.5e, however, also added a bunch of new categories which don't necessarily fit as well as Robin's originals do. So, let's look through and see how they've evolved.

Robin's first category was the Power Gamer, and this appeared in 3.5 as Accumulating Cool Powers. 3.5e claims that this is almost always popular, and that they're some of the easier players for a GM to deal with; as long as you keep the XP and loot flowing, they'll engage even with encounters balanced for other types. 4e, on the other hand, names them as the Power Gamer and suggests giving them moments to exploit their strengths but also attacking their weaknesses and having villains aggressively adapt to them - which can be a good idea, but can also result in a system-based arms race that turns out to be no fun (especially in a world with minmaxing forums). It does add that if you want your Power Gamer to engage with pretty much anything in the setting, just make it a source of power, and bingo. 5e, however, renames this motivation Optimizing - a rather awkward term given that optimizing tends to be something that happens away from the table more than during the game. As with most of the 5e versions, they've essentially just taken the paragraph headers from 4e and occasionally 3.5e and turned them into bullet points, although the ones about targetting the weaknesses of the power gamer are gone; it's only suggested that encounters highlight their strengths.

Next up was the Butt Kicker, which becomes, oh look, Kicking Butt in 3.5e; they're all about the thrill of combat. 3.5 emphasises that unlike power gamers, butt kickers tend to want more interesting and/or visceral fights, and suggests holding a fight or two in reserve to break up non-fighting play if they're needed. 4e instead names them as the Slayer, and has similar advice on interrupting other items with fights, plus making use of minions (yes, 4e had mook rules) to give quick kills and making sure that villains are strong and easy to hate. 5e simply changes this to fighting but ditches the advice on strong villains, but oddly does keep the one about large numbers of weak foes - which are much more awkward in 5e - and the ever popular advice to interrupt other activities with combat if you lose the players attention.

Robin's Tactician becomes 3.5e's Brilliant Planning; encouraged by giving players mapped, determined set-piece encounters with routes for planning to lead to victory. Even unlike the original Robin's Laws, 3.5e addresses the big issue of planning causing an anticlimax which is unacceptable to other players; the suggestion given is to big up the positive consequences of victory, so that there's a victory party for the method actors, some magic items for the power gamer, and some future effect on the world for the storyteller. Unfortunately, the Butt Kicker kind of gets it in the shorts.

3.5e introduces Puzzle Solving as a category - which I still think was rolled into Robin's Tactician, but there we go. Most of the text in 3.5 on the topic of this is how to deal with introducing puzzles to the game without stalling the game for everyone else, which is perfectly fair.

4e rolls the Brilliant Planner and the Puzzle Solver back into a single category, the Thinker, but with similar advice - although since 4e's combat system was more intrinsically tactical, most of the advice is to do with making sure that interesting features exist and that their consquences are visible to the player and PC before the fight starts so that they can be planned around. It also suggests adding extra clues to provide information for planning. Puzzle solving isn't so directly addressed. 5e, on the other hand, changes this back to Problem Solving and mentions unravelling motivations, solving puzzles, but only uses the "tactics" word once and not in a combat context. Which might be an admission that 5e combat without optional rules isn't all that tactical.

The Specialist gets retitled as Playing a Favorite Role in 3.5e, this time claiming that while ninjas are the most common, bards are the second most common, and even calling out Drizzt Do'Urden specifically as a character that's copied. Unfortunately, the advice given for this guy in 3.5e is rather week - basically, just hope they attach to a class, and then focus the adventure on that class's signature abilities.

Supercoolness is added to 3.5e even though it didn't appear anywhere in Robin's Laws, but 3.5 attaches it specifically to the "favorite role" player, saying that they also often want to be "icy cool, masterful, in command, formidable and intimidating". This is more or less just a lengthy preamble to the advice to be aware that RPG characters fail more often than movie characters, but that the failure can be made progressive rather than humiliating.

Fourth and Fifth edition both just left out the Specialist, in both of the forms above, presumably counting that class based play naturally encourages them.