Blade of the Iron Throne by hectorgrey

Chapter 1

Original SA post

So, as some of you may remember, I wrote about a game called The Riddle of Steel some time ago; it was an awesome game, with some features that I really, really liked and some that I thought were just a little bit dodgy (the lower is better skill system, for instance). Still, it's the first game I ever ran, and I still reckon the combat system more than makes up for the skill system. Anyway, there are a couple of successor games; one recently(ish) released, Blade of the Iron Throne, and one still in development, Song of Steel. I'm here to look at the former of the two, and ultimately see how it compares with the original. But to begin, a few words from the guy who ran the forum that kept this game going for far longer than any expected it to.

Ian Plumb posted:

Introduction

Eleven years ago today Jake Norwood and team were wrapping up development of their revolutionary RPG, The Riddle of Steel. The following March the game was released at GAMA -- andthe first print run sold out. A second printing soon followed and it is this version of the game that most players remember so fondly.

The fact that we’re still talking about a game that was released nearly eleven years ago, a game that hasn’t had any official material published for it in the last five years, a game that still has an active community behind it, is testament to the originality of Jake’s game. What attracted gamers to it all those years ago still holds true today -- player-driven story and detailed, realistic combat mechanics producing a true Narrativist-Simulationist hybrid that appeals to players and referees alike.

About two and a half years ago the trosfans community broached the subject of a successor game in earnest. Over the years many had asked whether a new version of TRoS could be produced, one that addressed the inconsistencies prevalent in the first edition. Issues over ownership and copyright ruled out that option and so the idea of a successor game was introduced. Ninety threads and nearly two thousand posts later every aspect of TRoS has been picked apart and alternatives suggested.

Upon this maelstrom of ideas order needed to be imposed. The greater pool of concepts needed to be gleaned, the numbers winnowed, until a coherent whole was formed. Who better to do this than two of the communities’ most active contributors? Phil and Michael had a clear vision for an RPG that worked seamlessly within the classic genre of Sword and Sorcery fiction.

Today, with Blade of the Iron Throne they have produced a successor to TRoS that has none of the anomalies, none of the inconsistencies, none of the gaps -- yet retains a clear link to TRoS through player-driven story and demanding, realistic combat scenes.

If Conan were to pick up a role-playing game, he’d choose this one.

Ian Plumb – December 2012

Bold words. True ones though? Let's find out.

Each chapter begins with two pages to separate them from the last; one with a quote of a few Paragraphs to get you in the mood, and one with a sentence or two along with the chapter number and title. So that's how I'll begin too.

Karl Edward Wagner posted:

A battered, gut-weary handful of hunted men – ruthless, half-wild outlaws hounded bykillers as remorseless as themselves. Shivering in their dirt and blood-caked bandages, theyrode on in grim determination, thoughts numb to pain and fear – although both phantomsrode beside them – intent on nothing more than the deadly necessity of flight. Flight from the hired bounty killers who followed almost on the sound of their hoofbeats.

They were well mounted; their gear was chosen from the plunder of uncounted raids. But now their horses stumbled with fatigue, their gear was worn and travel-stained, their weapons notched and dulled from hard fighting. They were the last. The last on this side of Hell of those who had ridden behind Kane, as feared and daring an outlaw pack as had ever roamed the Myceum Mountains.

No more would they set upon travellers along the lonely mountain passes, pillage merchants’ camps, terrorize isolated settlements. Never again would they sweep down from the dark-pined slopes and lay waste to villages on the coastal plains, then dart back into the secret fastness of the mountains where the Combine’s cavalry dared not venture. Their comrades were dead, fed ravens in a forgotten valley countless twisted miles behind their bent shoulders. Their leader, whose infamous cunning and deadly sword at last had failed them, was dying in his saddle.

They were all dead men.

And night was upon them.

Chapter 1: Mechanics

The Forlorn Tomb of Du'Karrn posted:

Ushered before it, they prostrated before this throne of iron, its visage as black as the ravaged souls of those votaries before it. But its stair granted none its purchase; It was an ebon boon that none could claim unless first claimed by it...

The book begins with the standard "What is an RPG?" section. It's about the same as every other such section, so I'll move straight onto the second bit - what makes this game different from other Fantasy RPGs. Simply put, this game is not a typical High Fantasy RPG. It's a Sword and Sorcery RPG. The major differences are twofold. The first is that typically in such stories, the heroes are men of action. While they may or may not be intelligent, they rarely hesitate to act when necessary. They have no need of divine intervention nor of the typically evil magics used by lesser men; they thrive on their wits and their blades.

The second is that Sword and Sorcery tends to be somewhat harsher than High Fantasy. The setting is harsh, and the heroes typically are too - they must be, in order to survive. They will kill and steal to get what they want, and not be troubled by it. In fact, there's typically only one thing separating them from the villains - the heroes don't stab their friends in the back. They respect honourable adversaries and their allies, but anybody else is fair game. Some show more compassion and kindness than others, of course, but even the nicer ones will kill and steal from people they don't particularly like for no other reason than that. There's more information about this later, so I'll get back to it then.

Next, the chapter discusses the different die rolls you may have to make, and the dice you use for them. I hope you've got a shitload of d12s... No, that's not a typo. This game uses a similar die rolling system to The Riddle of Steel, but instead of d10s, they use d12s. Maybe it's because they roll better, or maybe it's because the authors felt they needed more love. They also use d6s for some things, but unless I say otherwise, assume I'm talking about d12s. A check involves rolling a number of d12s, and each die that's equal to or greater than the TN (typically 7) is a success. The more successes you roll, the better you do, and sometimes you need more than one success to actually succeed.

Anyway, we have Attribute Checks, wherein you roll a number of dice equal to your attribute. For skill checks, you roll a number of dice equal to your skill, but it may be not be equal to or greater than double the most related attribute to the situation. For example, if Cunning is the most related to the situation, and you have it at a 3, you may only use up to 5 dice, regardless of skill. If you don't have the skill, you may roll the related attribute instead, but must get double the successes you would have otherwise needed. The third type of check is a Proficiency Check. They're typically made by choosing a number of dice out of a pool to roll (typically melee, ranged or sorcery), and rolling against a TN depending on the situation. If you roll two successes or more fewer than required (for example, only one success when you needed three), then it's a Complication; instead of a mechanical penalty, something happens in character that messes things up for you. These may happen on the spot, or later on.

In opposed checks, whoever gets the most successes wins. On a tie, the person trying to maintain the status quo wins - a thief sneaking past a guard wins on a tie, because the status quo is remaining undiscovered, but a thief picking someone's pocket loses on a tie, because the status quo is the item remaining unstolen. Pretty simple, really. If one party doesn't have the skill required, they roll the attribute as above, and must beat double the number of successes the person with the skill rolled. If multiple people are involved, each person rolls only once, and compares it with everyone. Here's the example from the book:

quote:

Otho makes his move at the ball and invites a rich old dowager (and her beautiful diamond necklace!) to dance. As they swirl about the dance floor he directs her to a somewhat unobserved spot and deftly attempts to remove the necklace. An Opposed Check with two antagonists to Otho is now called for:

The guard closest to the pair makes a Check of his Sagacity 4 Attribute, testing his powers of observation.

The dowager makes a Check of her Sagacity 3 Attribute, to determine if she is aware of the necklace being removed.

Otho will make a single Check of his Skill of Pick Pockets 6 against both. Otho needs to tie the guard’s result to pocket the necklace unobserved by the guard (the status quo being that the guard notices nothing special), but he needs to trump the dowager’s successes to filch the necklace (the status quo being that she has it).

Otho achieves an unlucky 2 successes, the guard an average 2 successes, and the dowager a somewhat lucky 2 successes. While the guard would have noticed nothing out of the ordinary, the dowager feels Otho’s groping fingers and raises a ruckus, leaving Otho to bluff his way out of a tight spot.

The last type of check we have is the timed check. This is where you need to achieve a certain number of successes within a certain number of rolls; each roll typically corresponding to a certain length of time.

Finally, we have attributes. There are six Basic Attributes (down from TRoS's five Temporal and five Mental), based on the attributes common to Sword and Sorcery heroes:

Brawn (BN), which covers your strength, endurance and ability to take physical punishment and not die from poisons

Daring (DG), which covers your courage, your ability to perform tasks like climbing and acrobatics, and your ability to attack and parry in combat.

Tenacity (TY), which measures your focus, determination and willpower.

Heart (HT), which covers your charisma and empathy. It's your main social attribute.

Sagacity (SY), which covers your mental agility. It covers your ability to notice things and make accurate logical leaps, as well as your general intelligence.

Cunning (CG), which covers your instincts, agility, reaction times and so forth. It's typically used for lock picking, hiding and sneaking around.

Next, we have the Passion Attributes; they are basically the same as Spiritual Attributes from TRoS, though the fifth one is always called Drama. These are player defined, and provide bonuses to to rolls, as well as being used in place of Experience Points. They are granted during play, and may be spent during play. The value doesn't measure how important the Passion is to your character; only role playing can do that. When you act according to your Passions, they get more points, which both give you bonuses and may be spent to improve your other stats.

The last kind of attribute is the Combined Attribute. These are:

Reflex: The average of Daring and Cunning, which determines reaction times. Used in melee combat.

Aim: The average of Sagacity and Cunning. Used in ranged combat.

Knockdown: The average of Brawn and Daring. Measures your ability to avoid being knocked on your ass by particularly powerful blows.

Knockout: The average of Brawn and Tenacity. Measures your ability to remain conscious when hit by a REALLY powerful blow.

Move: The average of Brawn, Daring and Cunning. Measures how far you can go on foot when you're in a hurry.

Sorcerers get a sixth one, named Power.

And here endeth the first chapter.

I hope you all enjoyed it.

Chapter 2

Original SA postFritz Lieber - The Swords of Lankhmar posted:

The chamberlain faced the big man. He drew a scroll from his toga, unrolled it, scanned it briefly, then looked up. “Are you Fafhrd the northern barbarian and brawler?”

The big man considered that for a bit, then said, “And if I am –?”

The chamberlain turned towards the small man. He once more consulted his parchment. "And are you – your pardon, but it’s written here – that mongrel and long-suspected burglar, cutpurse, swindler, and assassin, the Gray Mouser?”

The small man fluffed his gray cape and said, “If it’s any business of yours – well, he and I might be connected in some way.”

As if those vaguest answers settled everything, the chamberlain rolled up his parchment with a snap and tucked it inside in his toga. “Then my master wishes to see you. There is a service you can render him, to your own considerable profit.”

The Gray Mouser inquired, “If the all-powerful Glipkerio Kistomerces has need of us, why did he allow us to be assaulted and for all he might know slain by that company of hooligans who but now fled this place?”

The chamberlain answered, “If you were the sort of men to allow yourselves to be murdered by such a mob, then you would not be the right men to handle the assignment, or fulfill the commission, which my master has in mind.”

Chapter 2: Characters

The Forlorn Tome of Du'Karrn posted:

Thus born with untamed souls, those slayers prowled like wolves amidst the sheep that were their fellow men. No rules would bind them, and no courtesies keep them.

They thirsted for blood as others for wine, and drank lives with a bleak obstinacy and ardor merely kindled all the brighter by all whom would say them nay.

And so we come to character creation. As with The Riddle of Steel, this is done as a priority pick; six categories, A to F where A is the best and F is the worst. Unlike in The Riddle of Steel, they haven't left you a dump pick if you want to be non-magical. the first category is Sorcery, wherein A is a master of the arcane arts, D is entirely ordinary, E is particularly vulnerable to magic and F means that not only are you vulnerable to magic, but there's a magical being out there who wants to fuck your shit up. Which is, in all honesty, far more interesting than "D-F is just normal borderline humanity" - putting an F choice anywhere ought to be tough. Here, the game says to be very, very careful about putting your F choice here; your character likely won't survive it.

Next, we have Culture. This is another place where the game emulating the fiction becomes apparent; A is an Enlightened culture, such as Ancient Egypt or Ancient Greece at their respective heights. You get +1 to Tenacity, Heart and Sagacity, ten bonus skill points, you may always take the Occultism skills, you live one and a half times as long as regular humans and can do without food and sleep for very long periods of time, and a bonus Good Asset (read Advantage) related to culture or the supernatural.

B is Savage; think of the Picts and the Cimmerians from Howards work - just generally stronger and tougher than city dwellers because of their upbringing. They get +1 to Brawn, Daring and Tenacity, and five skill points to spend on outdoor skills.

C is Hillman/Nomad. They get the five skill points that Savages get, but not the improved attributes.

D is Civilised. This is a typical city dweller with neither advantages nor disadvantages.

E is Decadent. Think of the Roman Empire as it neared its collapse. Lots of drug abuse, demon worship, human sacrifice and slavery. People from such places have a -1 to Tenacity, as well as either a -1 to Brawn or a Poor Asset (Disadvantage) relating to minor mental handicaps.

Finally, F is Degenerate. Think of the antagonists of The Hills have Eyes. You get a -1 to three Attributes of your choice, and two Poor Assets based around physical handicaps and nasty mental illness (the examples here include Necrophilia). Yeah - if you take this, your character is likely to be truly sick in the head.

Third, we have Attributes. You pick a priority, you get a number of points to split between them, and they may be between 1 and 8 (assuming you don't have an adjustment from Culture), with one of them being your Focus, which no other may be higher than. You also get 7 points to spread between your Passion Attributes, which should be determined here.

Fourth are Skills. Pretty self explanatory, since I already mentioned how skill checks work earlier - higher is better, and nothing should be higher than an 8.

Fifth come Proficiencies. These measure your ability to fight, and are also used for any Sorcerous Knowledge you begin the game with if you chose to be a sorcerer. You get a number of points to spread between any number of weapon proficiencies you may wish to have, but you may not begin higher than a 12 on any one proficiency, while 13 is the highest you can reach in play.

Sixth, we have Assets. Basically, your Advantages and Disadvantages fall here. The higher your pick, the fewer Poor Assets and the more Good Assets you choose.

Once this is done, you can calculate all your Combined Attributes and Pools - your Melee Pool is Reflex + Proficiency (depending on weapon), while your Archery Pool is Aim + Proficiency (again, depending on weapon). The Sorcery Pool will be discussed when Sorcery comes up, a few chapters from now.

After that, we have a pretty detailed character creation example, where an example player creates the character often used in other examples within the book. Next, we have the Four Shoulds:

1. Your character should have a flaw that balances out their strength.

2. Your character should have his own way of speaking (please note, that if that includes an annoying accent, don't be too surprised if rocks fall).

3. Your character should be played in a realistic manner.

4. Characters should interact with each other.

This is where the book suggests that you might even have a reason for your characters to dislike each other. While that's usually a bad thing in gaming groups, this has to be done with the consent of the whole group. The idea behind this is that a little tension can make things more interesting, and even people who basically like each other can get on each others' tits sometimes.

Finally, we have advice on creating a different Priority table, if the one given doesn't suit our preferred setting. The way they designed theirs was such that D was average, E was noticeably but not horribly worse, while F was meant to be horrible - three times as bad as E. C, meanwhile, was as much better than D as E was worse, B is twice as good as C, and A is twice as good as B, when compared with D. If that makes sense.

And this is where the second chapter ends. Once again, I hope you all enjoyed it.

Chapter 3

Original SA postJewels of Gwahlur - Robert E Howard posted:

The oracle chamber held no clue for him. He went forth into the great throne room and laid his hands on the throne. It was heavy, but he could tilt it up. The floor beneath, a thick marble dais, was solid. Again he sought the alcove. His mind clung to a secret crypt near the oracle. Painstakingly he began to tap along the walls, and presently his taps rang hollow at a spot opposite the mouth of the narrow corridor. Looking more closely he saw that the crack between the marble panel at that point and the next was wider than usual. He inserted a dagger point and pried.

Silently the panel swung open, revealing a niche in the wall, but nothing else. He swore feelingly. The aperture was empty, and it did not look as if it had ever served as a crypt for treasure. Leaning into the niche he saw a system of tiny holes in the wall, about on a level with a man’s mouth. He peered through, and grunted understandingly. That was the wall that formed the partition between the alcove and the oracle chamber. Those holes had not been visible in the chamber.

Conan grinned. This explained the mystery of the oracle, but it was a bit cruder than he had expected. Gorulga would plant either himself or some trusted minion in that niche, to talk through the holes, the credulous acolytes, black men all, would accept it as the veritable voice of Yelaya.

Remembering something, the Cimmerian drew forth the roll of parchment he had taken from the mummy and unrolled it carefully, as it seemed ready to fall to pieces with age. He scowled over the dim characters with which it was covered. In his roaming about the world the giant adventurer had picked up a wide smattering of knowledge, particularly including the speaking and reading of many alien tongues.

Many a sheltered scholar would have been astonished at the Cimmerian’s linguistic abilities, for he had experienced many adventures where knowledge of a strange language had meant the difference between life and death.

Because Barbarians are just better, and black people are just dumb in the world according to Howard. And people wonder why I'm not a huge Conan fan... Anyway, it's time for:

Chapter 3: Training

The Forlorn Tome of Du'Karrn posted:

“Thus tempered in the fire of conflict and strife, each slayer discovers that he holds a flame locked within his very heart, a blaze of passion that must ever char his soul lest it instead betray him to his enemies.

And while it may flicker and waver in time, only death can truly quench this fire, yet until such time, it shall seek to consume him – or be unleashed upon those who would oppose him.”

Unfortunate opinions from the early twentieth century aside, this chapter is all about Skills, Proficiencies and Assets, and how to improve them. The game describes Skills as a more specialised use of an Attribute, for example, Ancient Languages as a more specialised use of Sagacity. They work as you might imagine, though I'll introduce a few here that I think do things interestingly.

Ancient Languages is naturally used to learn a dead language. At levels 1-3, you can understand the writing system, while at 4-6, you can start working out how it might have been spoken. Around 7-9, you can actually speak the dead language quite well - it's not particularly realistic, but it does reflect the source material. Also, every skill point put into this at character creation counts for two skill levels, and each language is naturally a separate skill. You must be literate to take this skill.

Decipher may be used to understand any unknown text, including unknown languages, but it doesn't allow you to retain any knowledge of the language and it takes far longer than if you actually spoke the language itself.

Detect Sorcery does exactly what it says on the tin, and is only available to people with magical talent.

Falsehood is used with Heart for telling lies, and Sagacity for detecting lies. Yep - lying and knowing when you're being lied to are the same skill.

Light Steps is one of the only skills you can't use an Attribute for. It allows you to walk through mud and leave no footprints, or to step across pressure plates without setting them off. You could use it to walk on rice paper and not tear it, if that were somehow important.

Prestidigitation lets you do magic tricks, but doesn't allow you to pick pockets; that is its own skill.

Soldiering is a skill common to all soldiers. It includes kit maintenance, how and where to set up camp and, most importantly, it may be used as your Weapon Proficiency in formation fighting, regardless of the weapon used. Your normal proficiency may only use up to 20% of its usual amount, while Soldiering may be used in its entirety. If you break rank and fight by yourself, which endangers both yourself and your unit, you may use your whole proficiency, but may not use Soldiering.

The book recommends that anything not listed, if it isn't commonly used in the story, should not be a skill. Your character might be an awesome cook, but that should just be background detail unless impressing people with your cooking is actually likely to come up regularly in the campaign. That being said, if anything is likely to come up regularly, then by all means make it a skill.

Next, we have Assets. Again, I'll just point out a few examples, rather than listing them all. The interesting thing to note here is that you can have them as either a good or a bad thing, and in some cases, they'll affect the way your character behaves in the same way but for different reasons.

Absent minded - As a Good Asset, you reduce the TN on learning things by 2; as a Poor Asset, you increase the TN to notice things going on around you by 2.

Aggressive - As a Good Asset, you reduce the ATN on all attacks by 1 until you try to defend. As a Poor Asset, you increase the DTN on all defences until you successfully attack. So either way, you'll prefer an aggressive start to the fight, but for different reasons.

Brawler - As a Good Asset, you reduce the TN on all unarmed attacks and grapple checks by 1; as a Poor Asset, you increase the TN on all attacks at medium range or longer (weapons have ranges, I'll get into that when we reach Proficiencies).

Eunuch - As a Good Asset, you were castrated after puberty, so you appear to be a man for all intents and purposes (kinda like if you get a vasectomy), but treat seduction attempts by sexually compatible characters as if they were sexually incompatible. As a Poor Asset, you were castrated before puberty, so it's quite obvious that you're a eunuch, and most people who don't know you will react poorly.

Literacy - This depends on the setting. In a setting where literacy is not the norm, this may be taken as a good asset to be literate; in a setting where literacy is the norm, it may be taken as a poor asset to not only be illiterate, but to never be able to become literate.

Shadow - As a Good Asset, you reduce the TN on all checks to remain unnoticed by 2. As a Poor Asset, you increase the TN on all checks to be noticed by 2.

Next up, we have Proficiencies. Each Proficiency relates to a method for using a weapon, and may be used at a minor penalty to use similar weapons. Once you buy a Proficiency, you may no longer default from another if that would be higher, but you buy the Proficiency at one higher than that default.

Brawling is mostly unarmed, but also includes such weapons as knuckle dusters and saps. Daggers only take a -1 penalty.

Cut and Thrust is used for fencing type swords, such a rapiers and sabres. You may not use a shield with this proficiency, but you may use a dagger, arming glove or buckler in your off hand.

Dagger is pretty self explanatory, and does not include throwing the weapon.

Great Sword is for the really, really big swords; the six foot or longer doppelhanders of Germany, for example.

Lance is really self explanatory, and may only be used from horseback.

Longsword is for swords that are designed to be wielded two handed, but aren't as long as the great swords; a typical bastard sword, for example. They may also be used in only one hand with a shield with the Sword and Shield proficiency, but are designed to be wielded with both.

Mass Weapon and Shield is for using a mace, flail or axe with a shield.

Pole arms is used for everything from a spear to a halberd; a staff to a pike.

Spear and Shield is pretty self explanatory, though it may only use short spears.

Sword and Shield is again pretty self explanatory.

Wrestling is used for grappling checks; typically used if you find yourself unarmed when dealing with an armed foe.

Missile Proficiencies work the same way, for their individual type of missile weapon.

Next, we go into manoeuvres. This is how combat works in this game, and in its predecessor. Simply put, everything you do is a manoeuvre, from stabbing or cutting to disarming or parrying and attacking in the same smooth motion. A couple of the more interesting ones include Half Swording - the technique of using a sword like a spear in order to drive it through armour, the Murder Stroke - the technique of holding a sword by the blade and using the sword like a mace, and the Counter, where you take a small penalty to defend in exchange for a potentially huge bonus to attack right afterwards.

This is where we look at character progression. As I'm sure I mentioned, you receive and spend points in your Passion Attributes in play. You may change these Passion Attributes in play too, so long as the whole group agrees that it makes sense. Every point you spend is added to your karma pool, and when your character dies or retires, you may spend karma to create a better character; avoiding having to take an F pick in your priorities. Even the GM receives Karma - he gets as much Karma as the highest amount gained that session, so that if someone else takes over running the game, he can create a character on a par with those currently involved in the game, rather than having to start from scratch.

Drama, the fifth Passion Attribute, is typically used for introducing aspects to the environment beneficial to the character, requesting specific scenes, automatic success in a die roll and "stealing the limelight", which will be discussed in the combat chapter. It may also be used to avoid death. NPCs may use Drama - the GM offers each player in turn a Drama point to let him, and all of them must decline for it to be disallowed, and it may only happen, at most, once per scene.

Finally, we have the Loot system. Simply put, you have a Loot rating that determines what you can afford. Because characters in this genre typically have trouble keeping hold of money (they tend to spend it mostly on booze and whoring), die rolls may be required as time passes to keep your Loot at the same level. If you have the Wastrel Poor Asset, this roll becomes harder.

And here endeth the third chapter. Next up is Combat. I hope you enjoyed.

Chapter 4

Original SA postThe Spawn of Dagon - Henry Kuttner posted:

Two streams of blood trickled slowly across the rough boards of the floor. One of them emerged from a gaping wound in the throat of a prostrate, armour-clad body; the other dripped from a chink in the battered cuirass, and the swaying light of a hanging lamp cast grotesque shadows over the corpse and the two men who couched on their hams watching it. They were both very drunk. One of them, a tall, extremely slender man whose bronzed body seemed boneless, so supple was it, murmured:

“I win Lycon - The blood wavers strangely, but the stream I spilt will reach this crack first.” He indicated a space between two planks with the point of his rapier.

Lycon’s child-like eyes widened in astonishment. (…) He swayed slightly as he gasped, “By Ishtar! The blood runs uphill!”

Elak, the slender man, chuckled. “After all the mead you swilled the ocean might run uphill. Well, the wager’s won; I get the loot.” He got up and stepped over to the dead man. Swiftly he searched him, and suddenly muttered an explosive curse. “The swine’s as bare as a Bacchic vestal! He has no purse.”

Lycon smiled broadly and looked more than ever like an undersized hairless ape. “The gods watch over me,” he said in satisfaction.

“Of all the millions in Atlantis you had to pick a fight with a pauper,” Elak groaned.

Yeah, I'm bored and have nothing better to do, so I'll do another chapter.

Chapter 4: Melee

Noggrond Namebreaker, the Magnificent Shield of Lamu, High Priest of Yot-Kamoth posted:

“Behold these warriors, each with a soul of steel forged in a thousand battles and of a fearless cunning honed in our age of misery – my flawed tools of mayhem. Defy them and despair, for they be my blades and none shall stand against them.”

Those of you who have played The Riddle of Steel (or at least read my write-up of it) will recognise much of this chapter. That being said, some things are described better here than in The Riddle of Steel, while some other things are changed. The book starts by explaining the concept of "The Limelight" as it applies to combat. Simply put, the combat system in this game is designed around one vs one and one vs many fights. The Limelight refers to which particular fight is being run at any given time. All other fights are assumed to have nothing interesting happening at that point, or else it's assumed that you'll catch up when a given Limelight is over. A good time to switch limelight is whenever something interesting happens. Alternatively, if a player wants to do something immediately (typically because they have something actually worth doing based on what just happened), they may spend a drama point to "steal the limelight" and act immediately. Archers can get good use out of this - if an ally is in trouble, they can shoot at the person attacking them, for example. However the limelight switches hands, time during combat is broken down into rounds, which are of indeterminate length (enough time for a person to attack twice). Each round is further divided into two exchanges.

A combat starts with declarations of stance and intent. An agressive stance gives you a +2 bonus to your MP for attacks in your first round, but a -2 penalty to defend, while a defensive stance does the opposite. A neutral stance, naturally, gives neither bonuses nor penalties. Your stance lasts only for the first exchange of the first round - after that, all bonuses and penalties are gone, and both combatants must disengage completely if they wish to regain their stances. Intent is as simple as whether you wish to attack first, or wait and see what your opponent does. Both had advantages and disadvantages, but if your opponent is likely to attack first, it's typically wiser to defend than to try and beat him to it - after all, if you're attacking, you're not defending (usually).

Once you know who is attacking and who is defending, each combatant declares which manoeuvre they're going to use, and assigns a number of dice out of their Melee Pool. If both combatants are attacking, then the one with the higher Reflex chooses whether to declare first or second (on a tie, compare Cunning; if that's a tie, compare Proficiency; if it's still a tie, toss a coin), before an opposed Reflex Check determines who strikes first, with bonus dice granted to the person with the longer weapon, depending on reach. If it's a tie, then both attacks hit simultaneously. If only one combatant is attacking, then the attacker declares first, then the defender, and then it's an opposed check to see whether the blow lands. Either way, whoever is attacking declares the location they're attacking at the same time.

If both combatants are attacking, the one who strikes second may attempt to steal the initiative (if they're striking at the same time, the faster one gets the opportunity to try first, as determined by the Reflex comparison for declarations. This costs dice from the Melee Pool equal to half the opponent's Sagacity, and forces an opposed Cunning vs Daring check with the weapon ranges adding bonus dice to the combatant with the longer weapon, and the person initiating being able to add further dice from his MP, up to a maximum of his Daring. The winner strikes first; the loser (if still able to) strikes second. On a tie, both strike simultaneously. Either way, whoever had the initiative stolen may choose to steal it back, and back and forth until one person no long has any dice to steal with.

Anyway, this is where the first real differences between Blade of the Iron Throne and The Riddle of Steel in terms of combat show up - in determining damage. Once the attacker has successfully dealt a blow, he takes his Quality of Success (the number of successes he beat the defender by), and adds that to half his Brawn (rounded up) and the damage rating of his weapon - along with anything else he should add based on manoeuvre. That is then compared with half the defender's Brawn (again, rounded up) and armour rating against the damage type taken to get the wound level (between 0 and 6 where 0 is a scratch and 6 is typically a lost limb). In The Riddle of Steel, a fairly common complaint was that it was almost impossible for really strong characters to deliver just a flesh wound, and it was almost impossible to hurt someone with sufficiently high toughness. So here, the effectiveness of Attributes is halved.

The second difference is in the effectiveness of armour - each type of armour has three values - vs piercing, vs cutting and versus bashing. Metal armour, being almost impossible to cut through with any kind of bladed weapon, doesn't have a vs cutting value; instead, the blow does bashing damage, and is compared with the vs bashing armour value. For this reason, every bladed weapon has a bashing damage rating - it's typically quite low - though the vs bashing values of the metal armours are also typically quite low, making blunt weapons typically more useful than bladed against armoured foes.

Anyway, once the wound level is determined you look up the result and the location of the hit, then apply the affects. Damage is not cumulative in this system; instead, you receive wounds. Each wound causes blood loss, which slowly kills you over time, pain, which penalises your skill checks and your Melee Pool, and is reduced by Tenacity, and shock, which reduces your melee pool immediately. Only the worst wound in a given location counts, but a lesser wound the same location inflicts shock equal to the worst wound; similar to how someone punching you where you've got a broken rib would hurt far more than being punched where you're completely uninjured.

Once all this is done, whoever was successful in the previous exchange is the attacker, and may now attack as above with their remaining Melee Pool, while the defender defends with whatever they have left. After that, it's a new combat round, and the melee pools refresh; reduced for pain and blood loss.

You may be wondering why you wouldn't just throw all your dice into an attack right from the off. The answer is that it's a massive gamble. If the enemy has a higher MP than you, they might use just as many dice to defend, and then attack you with what they have left. If they're similar to you in ability, they may use the Counter defensive manoeuvre for all their dice; if they successfully defend, they get bonus dice equal to your successes to hit you in a random location with - with you unable to defend because you used all your dice.

At the end of each Limelight, if a combatant is bleeding he needs to roll a Brawn check, requiring a number of successes equal to his current Blood Loss. On a failure, he takes a -2 penalty to Melee Pool, Archery Pool and Sorcery Pool, while all Attribute and Skill checks require an additional success for every -4 penalty from blood loss. The Brawn check to not bet worse is exempt. If the number of required successes equals the character's Brawn, the character passes out from blood loss and will soon die. At the end of every round of Limelights, if he hasn't been treated, he makes another Brawn check for Blood Loss. If he fails, he dies. Even when fully treated, Blood Loss takes days to fully recover from. The lesson? Avoid getting stabbed. It fucking sucks.

After this, the book discusses Terrain Checks. These are pretty simple; they're used to keep your footing in bad terrain, to only fight one enemy out of a group through better positioning, and anything else involving movement; positioning is pretty abstract in this game, since it's assumed that you're almost constantly moving. You can only be attacked by up to three people at once; more than that and they'd get in each other's way.

Next up is Fatigue. At the end of every Limelight, combatants must do a Brawn check, and require successes equal to their current Encumbrance + 1. This acts the same way as, and is cumulative with, Blood Loss, but a full Limelight spent resting will reduce the penalties back to 0.

There is, naturally, an optional rule called Barbarian Chic. Basically, if your players are absolutely desperate to dress in chainmail bikinis, or in the case of men wander around entirely topless, this gives them a -1 to all activation costs, or +1 bonus to the roll if the activation cost is already 0, so long as their current MP is at least 1.

Ranged combat come next. A ranged attack takes one Limelight; whether you're using a crossbow, a longbow or a throwing dagger. If you need to move first, you roll a Terrain Check using your AP, and then you use whatever dice you have remaining in the pool for your attack. You may also use a Terrain check if you're being charged, to take down your attacker before he reaches you. Range provides penalties, as you might expect, and due to the difficulty of aiming for a specific place with muscle powered ranged weapons, the target location is determined randomly, though you may move one result higher or lower for every die from your AP you put to one side for that purpose.

After that, there's Mounted Combat. It works exactly as you'd expect; you get a bonus against people who aren't on horseback, and you may make a terrain roll followed by an attack roll to ride by someone and attack them while doing it; there's only one exchange per round, because you've already gotten back out of reach after the attack is done. Then we have Combat versus Animals. This comes with its own set of manoeuvres and target templates, but otherwise is identical to regular melee combat.

Finally, we have an example of combat. It's pretty clear, though at two pages it's pretty lengthy (TL;DR - a PC owns two NPCs using terrain, stolen initiative and a nice axe):

Example posted:

Skold Skullsplitter, the Danish reaver, has just plundered some foul deity’s sacred jewel from its shrine among the Orkneys. Trying to make his way back to his ship, two pursuing Pictish savages catch up with him on the rocky beach and rush him.

Skold Skullsplitter

BN 7, DG 6, CG 5.

Ref 6, Polearms Proficiency 10, PA bonus dice 3, MP 19.

Sleeveless metal scale shirt down to (and including) groin (Piercing AV 4).

Metal helmet for top of head only (Piercing AV 6).

Long-hafted axe, used two-handed (Reach M: ATN 7, DR +2, DTN 7; Reach L: ATN 8, DR +3, DTN 8; DR +1 against armor, Shock +1)

Pictish Savages

BN 5, DG 5, TY 5, CG 5.

Ref 5, Kdown 5, Spear & Shield Proficiency 5, MP 10.

Short-sleeved leather jerkin down to (and including) groin (Cleaving AV 2).

Hardened leather helmet for top of head only (Cleaving AV 2).

Short spear, used one-handed (Reach M, ATN 8, DR +1, DTN 7).

Small shield (DTN 6).

As the Picts rush at Skold, the ref informs the player that the combat will take place on particularly bad footing – the wet rocks of the beach – necessitating a deduction of 2 dice from all combatants’ MPs, bringing them down to 17 and 8 respectively.

At the outset of Combat Round One, the refree declares that the Picts’ charge puts them into an aggressive stance and that Skold, seeing them rush at him, has time to prepare himself and declare a stance as well. Wanting to finish this combat before more Picts can arrive, the player has Skold assume an aggressive stance as well and also announces that Skold is going to move in such a way that one Pict is between himself and the other, preventing the second Pict from attacking him right away. This necessitates an (Unopposed) Terrain Check, with 2 Successes required. The player commits 5 dice (taking his MP to 12) and rolls, achieving 4 Successes (1, 10, 10, 11, 11), for now easily avoiding the second Pict among the rocks and boulders.

The Pict’s intention to attack is apparent from his ferocious charge, and the player declares Skold as attacker as well. As both combatants have assumed aggressive stances, their MPs receive 2 bonus dice each, for 14 and 10 respectively.

With both combatants attacking, an Opposed Reflex Check will determine who attacks fractionally first, but Maneuvers and dice must be assigned before this Check. The player announces a Cleave from diagonally above at the Pict’s head and shoulders (Target Zone 4) for 11 dice, executed at Reach Long. The ref declares a Thrust at the groin (Target Zone 10) for all the Pict’s 10 dice.

Both combatants’ Reflex is then Checked, with a TN equal to their weapon’s ATN; as the Pict’s spear has Reach M and Skjold’s axe Reach L, Skjold receives a +1 die bonus and the Pict a corresponding 1 die penalty. Skold rolls 7 dice (Reflex 6 +1) against TN 8, achieving but 1 Success (1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 6, and 9). The Pict rolls 4 dice (Reflex 5 –1) against TN 8, achieving 4 Successes (8, 11, 12, 12) – the Pict goes first!

The player has however an ace up his sleeve and has Skold attempt Stealing Initiative. He pays the Activation Cost of 2 dice (half opponent’s SY), and after his previous bad luck decides to play it safe and purchase 1 bonus die for the Check, for a total Activation Cost of 3 dice. This uses up the uncommitted remainder of his MP. The Pict checks DG, with a flat penalty of 1 for having the weapon with shorter Reach, and Skjold his own CG, with a flat bonus of 1 for having the weapon with the longer Reach, and the 1 purchased bonus die. Skold thus rolls 7 dice (CG 5 +1 +1) against a static TN 7, achieving 3 Successes (2, 2, 5, 5, 8, 9, 11). The Pict rolls 4 dice (DG 5 –1) against a static TN 7, achieving 2 Successes (3, 4, 10, 11) – just as the Pict thrusts with his spear, Skold’s axe comes down hard.

Skold attacks with the MP dice previously committed, rolling 11 dice against ATN 8 and achieving 5 Successes (1, 1, 3, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 11, 12). The Pict cannot defend, so the attack QoS is 5. The player rolls d6 on the Cleaving Damage Tables to determine the exact hit location, achieving a 3 for a result of a cross-cut across the Pict’s chest, which is protected by his leather jerkin.

The Impact Rating is determined by then taking the QoS (5), adding half BN (4), and adding DR (3 +1 for striking armor), for a total of 13. From this Impact Rating is subtracted half the Pict’s BN (3) and his chest AV (2), for a remaining total of 8, corresponding to the maximum Wound Level of 6. As the Pict is just a mook, the Level 6 injury kills him instantly, without any need to consult the Wound Tables.

As Skold has neither MP nor opponent remaining, there is no second Exchange to this Combat Round, and the second Combat Round commences with the remaining Pict charging Skjold across the rocky beach. The ref decrees that all fighters still have to deduct 2 dice from their MP for treacherous footing, and that Skold can only just turn in time to receive the charging Pict and cannot thus assume a stance. He announces that the Pict’s charge effectively puts him into aggressive stance.

Combat Round two starts with the declaration of attack or defence. The Pict is declared as aggressor, granting him 2 bonus dice from stance for a total MP of 10, and Skold as defender. Next, the aggressor declares Maneuver and assigned dice – he declares a Thrust with 7 dice at Skold’s crotch (Target Zone 10). Smiling evilly, Skold’s player declares a Counter, paying the Activation Cost of 3 dice and assigning 10 of his remaining 14 MP dice to it.

The Pict rolls his assigned 7 dice against ATN 8, with a penalty of 1 for having a weapon one Reach increment shorter than Skold, for a total of 6 dice, and achieves 3 Successes (1, 4, 6, 9, 10, and 11). Skold’s player rolls the assigned 10 dice against the axe’s DTN of 8, as per the Counter rules, achieving 4 Successes (4, 4, 5, 6,7, 7, 8, 9, 9, 10). With a defense QoS of 1, a sweep of the axe knocks aside the thrusting spear harmlessly and the attacker now on Exchange Two assumes the role of defender (with Counter, even a defense QoS of 0 would allow him to do so).

Exchange Two commences with Skold assuming the role of aggressor. The Pict has 3 remaining MP dice and Skold 4, but as per the Counter rules, Skold receives dice equal to the total Successes in the countered attack as bonus dice for his follow-up attack; as the Pict achieved 3 Successes, so Skold now receives 3 bonus dice, for an MP of 7.

The Exchange begins with the declaration of attack, with the player declaring an attack with all 7 dice, randomly as per the rules for the follow-up on a Counter. A d12 is rolled on Counter Table 3.3 to determine The exact nature of Skold’s attack, and yields a result of 2, a cross-cut at thigh height. The Pict declares a Block with his remaining 3 dice as his defense.

The player rolls the assigned 7 dice against ATN 8, achieving 4 Successes (2, 6, 7, 8, 8, 8, 11). The Pict rolls 3 dice against his shield’s DTN 6, achieving 2 Successes (2, 8, 10), for an attack QoS of 2. The player rolls d6 on the Cleaving Tables to determine exact hit location, achieving a 4 for a cut to the thigh, which is unarmored.

The Impact Rating is determined by taking the attack QoS (2), adding half BN (4) and weapon DR (3), for a total of 9. From the Impact Rating is subtracted half the defender’s BN (3), for a net total of 6, once again enough to kill a mook like the Pict without the need to look up the injury on the Wound Table.

Exchange Two of Combat Round Two ends with the second Pict falling down dead or dying.

Combat Round Three begins with the referee announcing that the 2 dice penalty for bad footing does not apply to the prone Pict, but that Skjold is still on bad footing; as he is the only combatant standing, he does not simply subtract 2 dice, but rather must pass a Terrain Check to avoid falling. The Pict is prone and thus at half MP, for an MP of 5. To this, Shock 15 from the preceding Exchange is applied; Thus bringing the Pict’s MP to 0, and the remaining 10 dice added as bonus dice to Skjold’s MP against the Pict, raising his MP for the Combat Round to 27.

Two Picts charged Skold Skullsplitter. He wheeled, getting one between himself and the other. Skold then brought his axe down a mere blink of an eye before his Pictish opponent’s spear thrust hit home, cleaving the savage’s chest to the spine and knocking him to the ground dead. He then wheeled to receive the second Pict, coolly swept aside his opponent’s spear thrust with his axe, and in the same fluid motion brought the weapon around in a narrow arc, dipping under the shield’s rim to sever the Pict’s leg just below the crotch. With the fallen Pict screaming on the ground and spurting out his life in but a few heartbeats, Skold leaves the scene of carnage.

So here endeth the fourth chapter. I hope you all enjoyed it. Until next time.

Chapter 5

Original SA postThe Legend of Deathwalker - David Gemmel posted:

As it neared, Druss saw that Shaoshad’s description was correct in every detail: two heads, one a bear, the other a serpent. What Shaoshad had not conveyed was the sense of evil that radiated from the demon. It struck Druss like the numbing claws of a winter blizzard, colossal in its power, dwarfing the strength of Man.

The bridge had narrowed here to less than ten feet wide. The creature coming slowly towards them seemed to fill the gap.

“May the Gods of Stone and Water smile upon you, Druss!”, whispered Oshikai.

Druss stepped forward. The beast gave a terrible roar, thunder deep and deafening. The wall of sound struck the axeman like a blow, pushing him back.

The beast spoke: “We are the Great Bear, devourers of souls. Your death will be agonizing, mortal!”

“In your dreams, you whoreson!”, said Druss.

Chapter 5: Travel and Health

Goran Karr of Khazistan, Warlord of the Barren Reaches posted:

Crossing the trackless wastes of this land I have learned harshly the small truths of armor in cowardice, and the vile deceit of secrecy in weakness… alas, only honest steel grants victory or death!

So here's the least interesting chapter in just about any RPG; the one that talks about travel time, natural healing and so on. Clearly the authors agreed - this is by far the shortest chapter in the book. This book begins with the rules for travel: there aren't any. Simply put, unless the journey itself is important to the adventure, getting from A to B should be largely abstracted; the GM should basically describe any memorable part of the journey, and then move on to the party being where they were travelling to. Meanwhile, the Players are given the opportunity to bring a scene to a close, or to ask for a given scene to happen as soon as practical - this costs a point of Drama, and is one of the mechanics for giving players narrative control over the game.

After this, we have the optional Encumbrance rules. They're pretty simple; having 6 or more, 11 or more, 16 or more and 21 or more each give one cumulative point of encumbrance, chain armour gives a single point and plate armour gives two. Encumbrance adds an activation cost to terrain rolls. That's as far as it goes, and it's completely optional.

Next up, we have healing. If you're bleeding, you need to be treated. A healing check will reduce the blood loss from a wound by 3 per success, though if it fails the blood loss increases by 1. On a botched roll, the blood loss doubles. If the blood loss is reduced to 0, the penalties from blood loss are reduced by 2 for every each passing day spent eating properly and resting, or by 1 for days of exertion. If the wound level is 3 or higher, the person doing the healing must have a 3 or higher in Healing. At the end of each week, you perform a Tenacity check against the unmodified pain of each wound (that is, the Pain before you subtracted Tenacity). If you succeed, the Pain of that wound is reduced by 1. Once the Pain reaches 0, the wound is completely healed.

Third, we have falling damage. Quite simply, you receive a number of wounds over several locations based off of the distance you fall, ignoring armour. Also, the number of zones affected may only be 2, or a quarter of the fall's distance in meters, whichever is greater. Once that number of zones has been reached, all further wounds are applied to the zones already affected.

Next, it's Generic damage, which is basically anything that isn't being stabbed, cut or bludgeoned, and has it's own damage table in the appendices. After that, we have poisons and diseases, which are both treated the exact same way. Poisons go along a progression track, and depending on how fast acting the poison is, the victim may have to roll once per limelight or once every few hours, or anywhere in between to avoid getting worse. As the poison progresses, the symptoms become worse but TN becomes lower. Once the progression reaches 6, the character falls into a coma and will die within half the progression time. The stronger a poison is, the more successes are required for the poison to not get worse. If you pass three in a row, you've survived the poisoning, and you'll gradually get better. Healing can help, by reducing the target number for the checks.

Finally, we end on another optional rule: It's Just a Scratch! Simply put, after each battle, you roll the higher of Brawn or Tenacity, and reduce the unmodified pain from wounds you've received by a total amount equal to the number of successes - if you reduce the pain down to 0, it's just a scratch. The example given is as follows:

quote:

Otho has 3 cuts received during the fight he just emerged from as victor:

• A Pain 1 cut to his hand

• A Pain 1 cut to his jaw

• A Pain 2 cut to his side

Rolling a TN7 Check vs. Tenacity (His TY is higher than his BN) he scores 3 Successes and opts to reduce the Pain 2 cut to his side down to zero, and to also get rid of the Pain 1 cut to his hand. The cut to his jaw he opts to leave as a dueling scar for the ladies to admire!

And here endeth the fifth chapter. Next up, Sorcery. Far more interesting.

Chapter 6

Original SA postThe City in the Jewel - Lin Carter posted:

In a vast chamber beneath the Tower of Skulls, Zazamanc he Veiled Enchanter set enthroned in Power. This throne stood on a dais composed of nine tiers of black marble, and it was carved from the ivory of mastodons, Set within the broad arms of this throne were the sigils whereby the Veiled Enchanter summoned the demons and genii and elementals that served his wishes in all things. At this hour he wore the Green Robe of Conjuration, and his left hand was set upon Ouphonx, the ninth sigil of the planet Saturn, which the Lemurians of his age knew by a different name. Under his right hand lay Zoar, the third sigil of the Moon. Before him, on a tabouret of jet, lay the Crossed Swords and the wand called Imgoth.

Amulets were clasped about his wrists and throat. Pendent upon his brow hung the talisman the grimoires named Arazamyon, and upon it a certain Name was written in runes fashioned of small black pearls.

The face of Zazamanc went masked this day behind a single tissue of pale green gauze; through it the cold pallor of his handsome visage gleamed like an ivory mask, and his eyes glittered with frozen malice.

Chapter 6: Sorcery

The Teachings of Myr'vaan the Jealous posted:

I offer you the wisdom of snakes, eldritch knowledge older than this mountain you scaled for my council: There is no knowledge that is not power, and no power that is not fleeting. Be wary therein, lest questions you would slake draw you beyond the precipice.

What would Sword and Sorcery be without the Sorcery? Just swords, obviously. But anyway, it's time to look at how this game tackles magic in a genre where magic is typically incredibly powerful, yet dangerous to its caster almost as much as to its targets. Well, for one thing, sorcery is not an academic pursuit. Nobody knows exactly how it works; they can at best make educated guesses. There is no understanding it, because it is a force completely alien to all we know - whether it comes as a barbed gift from alien gods or from any other origin. If it does come from other beings, then those beings always have their own agenda, one which is at best indifferent to the human suffering it causes, and at worst actually enjoying it. Basically, sorcery isn't about knowledge or understanding, it's about power, and a sorcerer is more likely to spend time sacrificing virgins than reading musty tomes.

Mechanically, sorcery relies on the Sorcery Pool. This comes from the Power Combined Attribute, which is Sagacity, Tenacity, Brawn and a bonus equal to the number of mysteries known divided by three (but never higher than the proficiency of the highest known), and the mystery he's using. The dice are split into two groups whenever casting a spell - a casting check and a containment check. Naturally, the more you put into one, the fewer you have for the other. The higher your Sorcery priority was, the lower your TN is for these checks - 6 for A, 7 for B and 8 for C. You roll the casting check first, and if that succeeds, you then roll the containment check. If you get as many successes in the containment check as the casting check, you succeed in containing the sorcerous energies. Otherwise, you gain 1 taint for every success you missed it by.

The higher your taint is, the harder it is to cast magic (you get a penalty to your Sorcery Pool) and the harder it is to interact with people and animals - they sense your strangeness, even if it's at a subconscious level. Every 12 hours, your taint goes down naturally by 1, so long as you haven't gained any more in the mean time. Alternatively, you may perform a 12 hour ritual of purification, which ends in a Power check against TN 7, where every success reduces your taint by 1. Finally, Taint Backlash is a serious possibility - if you have more taint than Heart, and you gain 3 taint in one go, you gain a minor but obvious physical affliction - a third eye grows somewhere conspicuous, you grow scales instead of skin, or anything else the GM can come up with.

Next, the book discusses the different mysteries. There are six Lesser Mysteries and two Greater Mysteries, which may themselves be combined to form Arcane Secrets. The first Lesser Mystery is Cursing, which requires either the victim or else something of their's close at hand to basically cause them to have a run of really bad luck, or else for a very specific bad thing to happen. The second is Enslavement, which basically involves controlling a person's mind. You may make a person perform just about any task, which they will do while ignoring all else, or you may make them see something that isn't there - a venomous snake around their waste instead of a belt is one of the examples given. The third is Mending, which is essentially magical healing. Mending may be used to cure wounds or lift curses, but can also be reversed to inflict pain. The sorcerer must decide whether they prefer the healing or the harming side of Mending, and then have a +2 TN penalty on the other side. The fourth Lesser Mystery is Prophecy - this basically allows the Sorcerer to get answers to questions. The fifth is Scrying. This involves leaving one's body as it rests in order to watch people as a disembodied spirit. Humans can't see you, but anything supernatural can, and sorcerers can feel your presence. The final Lesser Mystery is Witchfire. This doesn't need to be fire, but is basically a combat application of sorcery; from throwing fireballs to lightning from your arse. Sorcerers gain half their Power attribute as Armour against Witchfire - or their full Power if they know the Mystery themselves. Characters with an E or F in Sorcery, and are thus weak to it may not even use their Brawn to absorb any of the damage.

The first Greater Mystery is Goety - the ability to summon or banish demons. Demons typically require a sacrifice to be successfully summoned - virgins are traditional, but some aren't quite so picky. If you use a better sacrifice, you get a bonus to your SP. Once the demon is summoned, you may give it commands. Banishing a demon you summoned is pretty easy - banishing a demon summoned by someone else is less so. The other Greater Mystery is Necromancy. Necromancy is not used to create undead - though it can lead to such practices later - but is instead used to summon the shades of the dead and to question them.

Next, we have Arcane Secrets. These are limited to the most powerful of all sorcerers, and since sorcery isn't an exact science, you cannot research them. This must be obtained by other means. Demons may teach you, for a price; some cults may know one or two, or you may be able to learn from the ghost of a dead sorcerer, as a few examples. In order to learn an Arcane Secret, you must be proficient in at least one Greater Mystery. There are some examples listed below:

Abomination allows you to create a monstrous creature by performing a ritual over a pregnant woman every week for the first trimester. The birth will almost certainly kill her. This requires Goety and Mending. The Acolyte's Claw is a martial art which allows a sorcerer to empower his fists with eldritch energies. This also requires Goety and Mending. Animate the Dead is exactly what it sounds like, and requires Necromancy. Bind the Soul allows you to force the soul of a dead person into a living body, and again requires Necromancy. Blight is a combination of Goety and Cursing that makes the land in a large area less fertile - can be quite nasty if you curse a village with it. Chariot of Sorcery allows you to enchant a vehicle of some kind to make it better - using Goety and Necromancy, you may give it an untiring crew (or the ability to move without), an unusual type of movement, the ability to move when it wouldn't normally have such a thing, being bigger on the inside - yes, you can basically create the TARDIS with this, if you're powerful enough... Eldritch Effigies allows you to split into multiple versions of yourself - though only one of them houses your soul. Firestorm uses Cursing and Witchfire to attack a large area with one's Witchfire - it could be an army, or a city or any other sensible area, and over the course of a single limelight, or thirty seconds if not in combat, per success on the casting roll, it randomly targets people in that area. Hand of Doom uses Goety and Necromancy to rip an internal organ out of a person's body and into your hand. Death is typically quick after that. Master of the Beast allows you to control a specific type of animal. Mold the Flesh allows you to magically disguise yourself. Plague Wind and Portal are exactly what they sound like. Shake the Bones of the Earth allows you to create massive earthquakes. Whisper My Name In Fear allows you to instantly know if someone says your name aloud, who said it, where they said it and in what context, as well as who is with them.

Sorcerers may combine their efforts to cast a spell; the person with the highest Mystery score in what is being attempted takes the lead, and everybody else provides bonus dice. Any taint and backlash caused affects all casters fully.

Next, we have the Duel of Wills. This is very similar to melee combat, but naturally uses magical energies instead, and doesn't typically aim at specific body parts the way you do in melee. I actually prefer this way of doing magical combat to the way The Riddle of Steel handled it - it's far less book keeping, and it fits quite easily into the combat system already provided.

Finally, spells may affect multiple targets (not 'effect' as written in the book), but one success is removed for every target after the first, and for everything but Witchfire, the person best able to resist the spell makes the roll for all the targets; if he succeeds, everyone resists, while if he fails, everyone fails.

And here endeth Chapter 6. I hope you all enjoyed this; next up it's a guide to playing and running Sword and Sorcery campaigns. See you all then.

Chapter 7

Original SA postCyrion - Tanith Lee posted:

“Zilumi herself, forsaking her life of luxury and witchcraft, followed Hokannen into the desert, where, to demonstrate her heart’s change, she lopped her hair and left her fine clothes lying on the sands, and even her magic instruments she left, this mirror among them, through which she had worked the worst enchantments of all.”

Cyrion had not moved. “I know the tale. Many claim to own remnants of Zilumi’s possessions.”

“But this mirror,” said Juved softly, “this mirror will prove to you that it is a piece of wickedness.”

The watcher from the tower had by now resumed sufficient equilibrium to advance to the doorway. Reaching in and grasping Cyrion’s arm, he guided the young man from the bedroom, and back into the outer chamber.

“Did you feel the soul sucked from you, most elegant swordsman?”

Cyrion’s colour was reestablished. Blithely he said: “What gives you to suppose I have a soul?”

Chapter 7: Sword and Sorcery Gaming

Hen'r the Long-Hailed posted:

Thus he spoke to them: "Come here and kill me then, if indeed you can. But know this - within these walls, death ends nothing."

This chapter describes typical Sword and Sorcery settings. The introduction points out that not everything in here needs to be used; most authors don't use all of them at once, but you shouldn't ignore too much of it if you want to retain the Sword and Sorcery feeling - though of course, if that's not a priority then use as little or as much as you wish.

A typical Sword and Sorcery setting is a harsh place, where violence and cruelty are fairly common. The setting may or may not be lawless, but even when they aren't, the laws are typically for the benefit of the rich, or you may be so far from civilisation that the lawmakers can't really enforce it. Decent people do exist - and will show up frequently in stories from these settings - they are very much the minority; they're there to emphasise how selfish most people.

Meanwhile, the gods are typically distant. There are no miracles (unless you count Sorcery), and the gods are not generally seen as benevolent - they're actually seen as beings to be appeased.

By default, magic is real, though it may not be. Even when it isn't, it's certainly believed in. Typically, magic comes from a particularly powerful being with its own agenda - almost never one with humanity's best interests at heart. The people using it are very rarely nice people - at best, they tend to be shady and untrustworthy and are commonly the worst that humanity has to offer. As such, Sorcerers are rather good villains, and are only marginally suitable as player characters.

Also, magic is typically subtle and takes a long time to cast - with the exception of Witchfire and the Duel of Wills. Scrying, conversing with the dead and magical enslavement are all staples of the genre. They typically don't throw lightning from their fingers or mass produce magical items. In fact, magical items always have a story of their own, and are often the focus of an adventure - or even a series of adventures.

Racially, almost everybody is human in these settings - dwarves and elves are incredibly rare, if they exist at all, and are almost never familiar with human society in any way. Monsters aren't meant to be slaughtered en masse; typically you'll only see one in any given adventure, and the adventure will be to kill that monster. More often that not, if monsters appear in groups, the sensible solution is to beat a very fucking hasty retreat.

The heroes of Sword and Sorcery stories have certain things in common. For one thing, they're typically strangers, outcasts or outlaws; they don't often have any ties to the location the story takes place in. Also, they're typically of humble descent; commoners, former slaves and barbarians are the most common. When one comes from the higher classes, they'll usually have fallen from grace.

A hero lives by brawn and cunning; with a self suffiency that puts them head and shoulders over the rest of society. He's a man of action - when decision is called for, he doesn't hesitate. This doesn't mean that he's hasty, but that he's unafraid to act when needed. Also, as he exists in a harsh world, he himself must be harsh to not only survive but to prosper. The biggest difference between the hero and the villain, however, is that a hero treats others as they treat him. A merchant who tries to cheat him is fair game to be stolen from later (as is a complete stranger), while a friend, or even an honourable enemy, are typically treated with respect, and will almost never be stabbed in the back. The hero should never cross the line into truly antisocial behaviour.

As for the stories themselves, well, since the heroes aren't exactly knights in shining armour, the antagonists are rarely truly vicious people with nefarious plans that must be stopped; more often than not, they're either rivals or personal enemies - or maybe someone who was just unlucky enough to cross the party's path. Horror can provide a better model for stories involving monsters than traditional fantasy does. The locales, meanwhile, are typically either isolated places or highly decadent urban areas. The Antagonists should have their own plans that they will be enacting - if they PCs wish to stop them, then they need to be proactive. They need to act, and act decisively.

Next, there's a list of twenty tips for running Sword and Sorcery campaigns.

1: Go get some books - there's a bibliography in the back of the book, and this is a good place to get inspiration.

2: The fray's the thing - combat is the heart of this game, and should be run descriptively. Rather than simply naming a manoeuvre and a location, you should describe your actions.

3: Do it with style.

4: Subtlety is not a virtue - everything should be larger than life.

5: Everyone has a past

6: Don't loot the bodies - it's crass, and if you need anything you can usually get hold of it.

7: The entire world's a cliche - don't be afraid of stereotypes; play them up.

8: If it's not important, it happens off screen.

9: A game in motion stays in motion - if things slow down, introduce something to speed them up again.

10: It's not just about combat - what happens between the fights should be just as important as the fights themselves.

11: Mooks - don't try to make them tougher; they're meant to die in droves.

12: Eat your mooks; they're good for you - have a bowl of sweets that represents the mooks. If you kill a mook, have a sweet.

13: Let your players shine - don't worry about things like realism, because authors and movie makers don't...

14: Let your players fail - Players can smell a rigged game a mile off. The risk of failure makes the success all the sweeter.

15: Great villains never die: they come back in sequels!

16: Pain a picture - be detailed when describing the scene.

17: Let the players roll the dice - in large combats, the players might start feeling bored if they don't currently have the limelight. One way to avoid this is to have a player roll for the enemies.

18: Keep your villains on their toes - their mooks are trying to become chief lieutenant, and their lieutenants are trying to become the new boss, so they'll often be willing to sell out their superiors if given the motivation.

19: Give your encounters a hook - Fights should all have something interesting about them, whether it's the location or the tactics. There should never be a fight for the sake of having a fight.

20: Give your players small mysteries that they can solve, or not, as they wish. This means that if you have a larger one as part of an adventure, even the ones that don't really like mysteries shouldn't be too upset by it.

Finally, we have what they call The Rule of Iron: the rules of the game are not written in stone, and may be changed by the group as a whole, but not by the GM by himself. The whole group has to agree to change the rule before it can be changed. However, even if the rest of the group want to change a rule, the GM can veto the change.

Here endeth chapter seven. I hope you all enjoyed; the next chapter details the world of Xoth; a sample Sword and Sorcery setting.

Chapter End

Original SA postClark Ashton Smith - Nostalgia of the Unknown posted:

”The nostalgia of things unknown, of lands forgotten or unfound, is upon me at times. Often I long for the gleam of yellow suns upon terraces of translucent azure marble, mocking the windless waters of lakes unfathomably calm; for lost, legendary palaces of serpentine, silver and ebony, whose columns are green stalactites; for the pillars of fallen temples, standing in the vast purpureal sunset of a land of lost and marvellous romance. I sigh for (...) the strange and hidden cities of the desert, with burning brazen domes and slender pinnacles of gold and copper that pierce a heaven of heated lazuli.”

Robert E. Howard - The Devil in Iron posted:

The fisherman was typical of his race, that strange people whose origin is lost in the gray dawn of the past, and who have dwelt in their rude fishing huts along the southern shore of the Sea of Vilayet since time immemorial. He was broadly built, with long, apish arms and a mighty chest, but with lean loins and thin, bandy legs. His face was broad, his forehead low and retreating, his hair thick and tangled. A belt for a knife and a rag for a loincloth were all he wore in the way of clothing. That he was where he was proved that he was less dully incurious than most of his people. Men seldom visited Xapur. It was uninhabited, all but forgotten, merely one among the myriad isles which dotted the great inland sea. Men called it Xapur, the Fortified, because of its ruins, remnants of some prehistoric kingdom, lost and forgotten before the conquering Hyborians had ridden southward. None knew who reared those stones, though dim legends lingered among the Yuetshi which half intelligibly suggested a connection of immeasurable antiquity between the fishers and the unknown island kingdom.

Chapter 7 - Xoth

On Lands Yet Tamed - The Forlorn Tome of Du'Karrn posted:

The currencies of this savage land are coined from threefold metal: There is the silver of talking, the gold of brooding, and the steel of bloodshed.

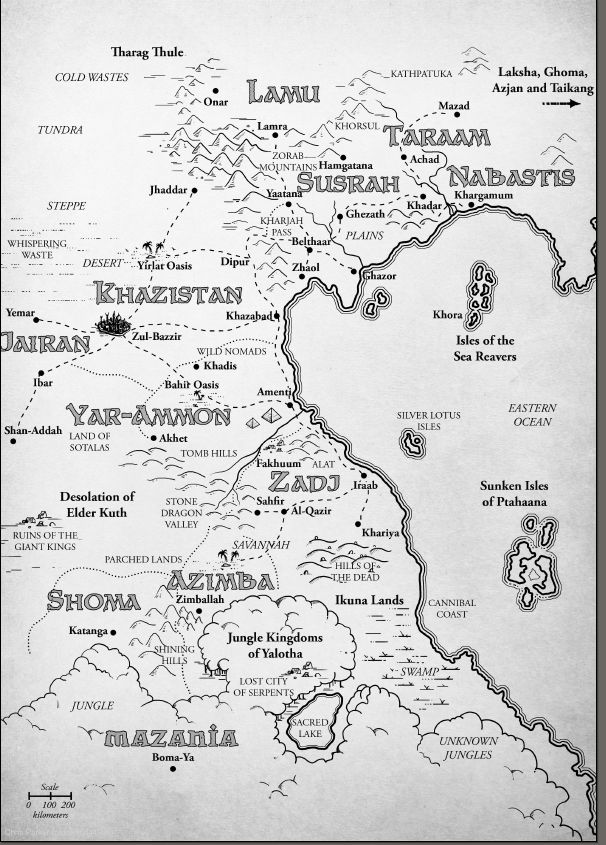

Sorry for keeping you all waiting - it took a while to get around to doing this bit. Xoth is the default setting for Blade of the Iron Throne, and the map looks a little like this:

There is no common language in this game - if the characters want to be able to talk to each other, they need to either come from the same place or take the related forein language skills - good job they're so cheap in character creation. There are many different peoples of many different ethnicities. There are everything from pigmies to giants; savages, stereotypical pirates and many, many others. Each race has a group of different cultural picks they can be; for example, most urban races may may be civilised or decadent, for instance.

Next, we have the Gods. The Gods don't exist. Or if they do, they're monstrous creatures that, at best, are completely disinterested in the fate of humanity, and at worst actively want to destroy the world. Blood sacrifice is common, and even human sacrifice isn't all that rare.

AHYADA - the High God of Taraam posted:

Ahyada is the bringer of truth and protection to the people of Taraam, and the patron of the royal house of Achad as well. He grants visions and omens to the king, which is interpreted by astrologer-priests and soothsayers. Amulets of Ahyada are said to be effective wards against demons.

AKLATHU - the God of Twisted Fate posted:

Figurines of this god, who has few temples and no priests, depict Akhlathu as a deformed dwarf, whose facial features even show a hint of retardation. Many Susrahnites swear “By Akhlathu’s Beard!” when in trouble. This is also a god of thieves and gamblers.

AL-TAWIR - the Ancient One, the Sleeper Beneath the Sands posted:

Some say that Al-Tawir dwells in the black gulfs between the stars, others that he sleeps in a sealed and forbidden tomb beneath the desert sand. Al-Tawir is one of the Old Gods. The nomads hear his voice in the howling of the desert winds, and they see his face in the rage of sandstorms. He is the emptiness of the desert, associated with getting lost, with thirst and hunger, with darkness, and with sandstorms.

BAAL-KHARDAH - the Sun-God of Susrah posted: