Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium by Halloween Jack

A Brief Exegesis on Why I Am Sad

Original SA post

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium or, A Brief Exegesis on Why I Am Sad

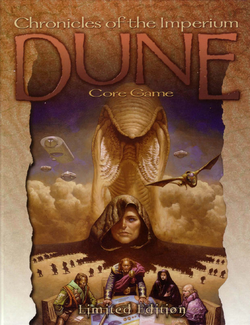

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is a roleplaying game set in the universe of Frank Herbert’s groundbreaking science-fiction novel Dune . It was published by Last Unicorn Games, a small company with a short list of properties that included some very well-known licenses and some very unique original works. LUG produced the Dune CCG and a uniquely weird CCG titled Heresy: Kingdom Come . On the roleplaying front, they were the publishers of Aria: Canticle of the Monomyth and a series of licensed Star Trek games. Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium would ultimately be the last gasp of Last Unicorn.

The game was designed primarily by Owen Seyler, with Christian Moore and Matthew Colville. (Seyler and Moore worked on Aria and Star Trek , and would later be involved in Decipher’s Lord of the Rings game.) They were still developing Dune when the company was bought out by Wizards of the Coast in 2000. Wizards allowed a “limited edition” of less than 2000 copies to be printed and sold at GenCon, and had big plans for a D20 version of the game. Matthew Colville discusses these plans in an amazing blog post which even has his outline for the game and the default campaign that would accompany it!

Matthew Colville posted:

WotC had this incredible mound of market data. They spent a lot of time and energy figuring out what people wanted to do in different universes. So they’d mention a property, like Dune and ask them to rate these statements:

“I would like to make an original character” rated 1 to 5.

“I would like to play one of the existing famous characters from this property.” 1 to 5.

“I would like to play through new adventures.”

“I would like to play through the classic storyline.”

They asked these questions about a wide range of potential gaming properties. Not only things you need a license for like Star Trek, Star Wars, and Dune, but stuff anyone could do, like King Arthur or Robin Hood. Amazingly, the same people answered differently for different properties. In other words, the desire to create a completely original character didn’t vary so much from person to person, as it did from property to property! Some properties, people overwhelmingly wanted to make their own stories. Some, people wanted to tell new stories. It was a revelation for us.

Well the data said that people wanted to play new, original characters in Dune, in the Main Storyline with the Kwisatz Haderach and everything you read in the novel, but they didn’t want to play the heroes in this story. They wanted the story of Dune to unfold as written, with their characters as sort of Rosencrantz & Guildensterning around. I believe the data indicated they wanted to have *some* influence on events, but not affect major changes.

It came to me to figure out how to make that adventure. Initially I thought “man this is going to be a pain in the ass, that’s some pretty fucking specific direction.” But I quickly realized I was completely wrong. As it turned out, it was easy. It was super easy. There’s a ton of amazing content happening right off-screen, in the novel, which they reference. Thufir says “We’ve sent an advance team to Arrakeen to clean out the palace,” YOU ARE that advance team. The first member of House Atreides on Arrakis! “We’re having the devil’s own time clearing out these sabotage devices, but we’re almost done,” because of YOUR work! Duncan mentions sending a continent to meet with Stilgar and how well that went, you play those characters, the first members of House Atreides to meet the Fremen.

According to Colville, one of principal reasons for the demise of Dune was an executive order for Hasbro not to make any licensed games. As for those “contractual issues,” I can only speculate, and speculate I will. Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson are not only listed as “creative consultants” on Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium , an interior title credits them as editors. I’m sure they would have prevented anything that conflicted with their own plans for the Dune universe.

Now, if you’re not a Dune fan, let me explain something quickly: Frank Herbert wrote six Dune novels (the last ending on a bit of a cliffhanger) and had plans for a seventh when he died. His son, Brian Herbert, supposedly discovered these notes on two floppy disks and some printed pages in a safe deposit box. Stories about the notes vary wildly, from “a 3-page outline” to “hundreds of pages of notes for future stories.”

In any case, Brian partnered with noted space opera author Kevin J. Anderson to release “Dune 7” in two books, and have since gone on to release over a dozen prequels and sequels to the original series. They are, to say the least, not critically acclaimed. Here’s what I think of the “Dune 7” notes and all the sequels and prequels based on them: Kevin J. Anderson offloads all the ideas that the Bantam editors considered too dumb for Star Wars , Brian Herbert puts his name on them, and the floppy disks were copies of Dig Dug and Centipede all along.

The failure to capitalize on the Dune franchise is almost a tragedy. Hell, Dune’s failures are more interesting than many other artists’ successes .

You see...let me explain something else about Dune . There’s a whole lot in the history of the setting, or happening far away from the main characters, which is never exactly defined. It’s one of the things that kept fans coming back for more. For example, we know that a civilization-spanning jihad occurs between the first and second books, but because of the weird, baroque nature of technology in the Dune setting, we can only imagine how a full-scale war plays out. We also know that computers, robots, and AI are forbidden because of a long-ago “Butlerian Jihad” against “thinking machines,” but Herbert repeatedly declined to describe exactly what happened and how. When Anderson wrote Dune: The Butlerian Jihad , he made it about swashbucklers with “pulse-swords” fighting cyborgs called “cymeks.”

This, I think, is why the Dune property is so underused, with the last attempt at a movie dying in development hell and no games of any kind since 2001. Nobody wants to publish a Dune title that is really just a Star Wars novel that is really just a rip-off of Battlestar Galactica . I can only berate Brian Herbert and KJH so much, because I’ve only read synopses of their books. Perhaps this is still hypocritical, but that is preferable to being the kind of nerd who reads an entire series of novels just to feel justified in hating them. As an aside, the only Kevin J. Anderson I’ve ever read was Jedi Search , a book I picked up in middle school. It features a barren planet where giant underground creatures create a substance which is mined for its ability to give people psychic powers.

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is not legally available in digital form, and remains one of the rarest and most expensive roleplaying games. Used copies, when they become available, go for $200-300 depending on their condition. There are some fanmade Dune games out there, including Dune: A Dream of Rain , a d20 fan supplement, Houses of the Landsraad , which uses Greg Stolze’s One Roll Engine, and a French game called Imperium , which has several supplements. I don’t know anything about it except that the PDFs are a) quite professional looking and b) only available in French, a language in which I only know words for weapons and brands of liquor. Luke Crane wrote Burning Jihad, a supplement for his game Burning Wheel. In true Luke Crane fashion, Burning Jihad is set during Paul’s Great Jihad, and specifically set up as a war between a group of Fremen jihadi and a rebellious Noble House, with the PCs playing as one of the sides. The jihad wins.

Long story short, this is the only official Dune roleplaying game that ever was or will be. Is it any good? Let’s find out.

Next time, on Chronicles of the Imperium : Introductions and a history of the Imperium.

Overview

Original SA post

Introduction

The book itself opens with a foreword from Brian Herbert, a few paragraphs of him fondly recalling his father’s voracious need to write, his vivid descriptions of his ideas for the books, and his mother’s suggestions. He also takes the opportunity to plug his upcoming Dune sequels. Fuck him.

Moving on, the designer’s opening notes state outright that they expect you’re either a Dune fan looking forward to experiencing it as a roleplaying game, or a roleplaying fan looking forward to experiencing Dune. After the obligatory “what is a roleplaying game” section, it gets right to the business of telling you what kind of characters you’ll play, and what you will do. The PC party is called the “House Entourage,” and that’s not just pomposity a la Immortal or Everlasting . The expectation is that the PCs will be playing the members and advisors of a minor House, and grow in power and prestige. The book is also blunt about telling us that while playing Paul & the Gang and recreating scenes from the books is possible, we’ll have more fun telling our own stories. They must have finished this part before they did all that fancy market research! They even promise us that in addition to Bene Gesserit and other emblematic roles detailed in the corebook, future supplements will support playing characters like spice smugglers and water merchants. Hoo, boy.

Space hippies! Space pharaohs! Space cotton plantation owners! None of these books were ever published.

Dune uses the Icon system, the same rules as LUG’s Star Trek roleplaying game. It’s a d6-based system designed to be “simple, elegant, and easy-to-use” but “open-ended and flexible.” Colville thought it was “not very gamist” and “awful.” We’ll see. The bit of advice for the Narrator is good--rules provide structure, but you’re going to have to use your own judgment, because no one is playing a Dune game so they can spend all night looking up rules.

I guess it’s time to end this chapter but oh look, the Icon Link!

Innovative, and very late-90s. The chapter wraps up with a brief glossary of setting and game terms.

Next time on Dune : A shorter history than the one in the back of the novel.

History of the Imperium

Original SA post

Chapter 1: History of the Imperium

Dune is divided into three “books,” the first being “Imperium Familia,” which contains all the setting, character generation, and rules info that the players will need. The first chapter is a history of the setting, the Imperium.

The Imperium is many thousands of years old, and the primary basis for the setting is a historical event called the Butlerian Jihad . The old Imperium was a peaceful community of over ten-thousand far-flung, technologically advanced planets. Unfortunately, relying on technology rendered them complacent, decadent, and stagnant, until it went a little something like this:

Discontent eventually broke out, and the elite responded by using more technology to isolate themselves from their disgruntled subjects. Within a generation, the Imperium went from its technological peak to being rife with widespread insurrections as rebel groups used artificial intelligences and “sentient weapons” to seize entire planets, and untold billions died as human civilization fell into anarchy and carnage. What followed was the Butlerian Jihad.

The Butlerian Jihad was a revolution that lasted a century and spanned the entire Imperium. It wasn’t just a rebellion against oppression by artificial intelligences and advanced weaponry, but an ideological crusade centered on the idea that men should not be controlled by machines, figuratively or literally. The Jihad purged human civilization of not only AI and robots, but automation and most computer technology. This laid the foundation for organizations like the Spacing Guild and the Bene Gesserit, who developed programs to breed, condition, and train humans to surpass the capabilities of machines.

The aftermath of the Jihad plunged the Imperium into a technological and cultural dark age, because faster-than-light travel was largely abandoned. When isolated planets began communicating with each other again, they did so with the shared philosophy that “Man may not be replaced.” The Orange Catholic Bible, a syncretic scripture created for the new Imperium, declares “Thou shalt not disfigure the soul.” What does that mean? No artificial intelligence, no robotics, no cybernetics, no genetic engineering; in short, no transhumanism and no reliance on automation. The Imperium has faster-than-light travel and gravity manipulation, but not Microsoft Excel.

(Although the Butlerian Jihad is a major part of the premise of the Dune universe, Herbert alludes to it many times without ever defining exactly what the conflict was or how it played out, not even in the appendix to Dune which lays out the background of the setting. We don’t even know who Butler was! Multiple allusions imply that it was both a literal war against Space Skynet and a neo-Luddite movement, but Herbert was a master of the “always leave them wanting more” principle. Dune: CotI takes a middle ground by saying that it was both. There’s some technology that seems like it couldn’t work without some computerization being involved, but as far as the Narrator and the players should be concerned, the Imperium is a sci-fi setting with no computers.)

We’re going to the bandolier store, and there better not be any smartphones in here when we get back!

Most of human history was lost during the Jihad, but as civilization rebuilt itself, planets forged new feudal alliances under the leadership of Great Houses, which mostly claimed legitimacy based on their ancient bloodlines. The Great Houses agreed that humankind should form another Imperium uniting human civilization, but disagreed on who should rule. They formed the Landsraad League, a loose confederation for mutual support and arbitration, but it lacked any real enforcement power of its own.

The fighting between the Great Houses came to a head at the Battle of Corrin , where House Sarda, its allied Houses, and its peerless Sardaukar troops defeated the remaining Landsraad supporters. The leader of House Sarda renamed his house Corrino, ascended the Golden Lion Throne, and declared himself the first Padishah Emperor of the Imperium. With the support of the Spacing Guild, who achieved a monopoly on interstellar travel, the new Imperium expanded throughout the Known Universe and reunited humanity under one government. Among the waves of refugees fleeing imperialism were the Zensunni Wanderers, who eventually settled on an obscure desert planet called Arrakis.

The New Imperium

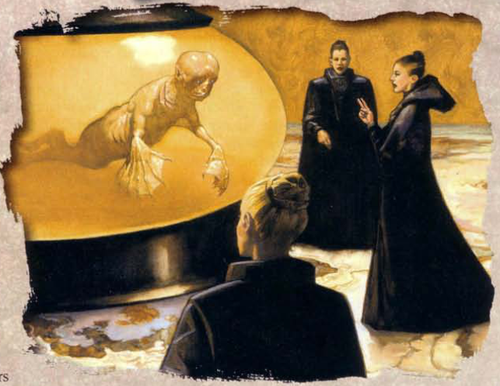

On Arrakis the Fremen discovered a drug called melange , or simply the spice , and soon, so did the Spacing Guild. (How it happened is a mystery, and neither the Guild nor the Fremen are talking--but it’s thought that when the Zensunni refugees moved on, the Guild learned about melange from them, while the Zensunni who remained on Arrakis became the fearsome Fremen.) Melange improves human health and extends lifespan; the only problem is that it’s addictive, and regular consumers of spice will die if they stop taking it.

Spice can also awaken prescient psychic powers. The Spacing Guild experimented with the spice until they discovered that it could replace the sophisticated sensors and computers that had previously been necessary for faster-than-light travel. With training and massive doses of spice, a Guild Navigator’s mind can transcend space-time and navigate a faster-than-light ship better than any AI. Not only did this pave the way for a new age of space exploration, it cemented the Guild’s monopoly on space travel.

As the Imperium regrew, the “ Great Schools ” developed to answer the question of how to improve the human condition without relying on machines. All of them have means of conditioning humans to achieve “superhuman” abilities. They are the Bene Gesserit, the Spacing Guild, the Mentat order, the Suk School, and the Swordsmaster’s School of Ginaz.

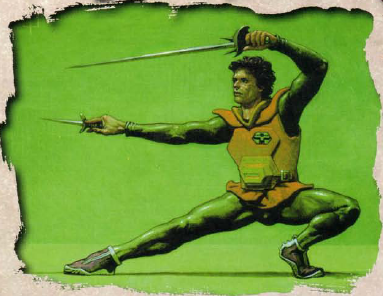

Do you know of a place where Swordsmasters hang out?

( Dune admits outright that of the four schools, only the Bene Gesserit and the Spacing Guild are major powers. But while Mentats are important to the plot of the Dune novels, the Ginaz swordsmen are only mentioned in a few passing references to give some background on why House Atreides has such great soldiers. But “swordsmaster” is going to be a character class in this game, so…)

The Bene Gesserit is an order dedicated to preserving and evolving the human race. In practice, that means they manipulate politics from behind the scenes. They nominally support the status quo, because the feudal caste system makes it easier for them to accomplish their goals. They literally control the breeding and training of royal bloodlines for superior genes, support their scions as political leaders to maintain “continuity in human affairs,” and they “seed” worlds with myths and cultural memes that their agents can exploit in times of need. (Arrakis is one such planet that was “seeded” and then forgotten centuries ago.) The Bene Gesserit is an almost entirely female order which recruits the young women of noble Houses, a tradition that’s been going on for centuries. (They do share limited degrees of their training with men, and in fact, one of their major projects is trying to breed the Kwisatz Haderach, a hypothetical enlightened male ruler with prescient powers their best members don’t have, who can lead the Imperium into a new age.) Everyone knows that the BG has a hierarchy and plans of its own, but frankly, their training is incredibly useful and nobody wants to be on their bad side.

You say “swordsmasters,” but you don’t just mean any swordsmaster, do you?

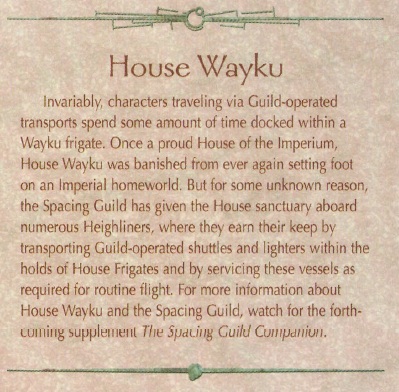

The Spacing Guild is an omnipresent but mysterious organization with an absolute monopoly on space travel. Although FTL technology was never lost during the Jihad, the Spacing Guild has perfected the art of training Navigators to pilot them better than any AI. Their Guild Heighliner transports are so massive that a Great House can pack all its assets (including people and buildings) into a corner of one and move its seat of power to a different solar system. Not only that, but the Guild enforces absolute neutrality, so a rival House can be doing the same thing in the same Heighliner without any fear of treachery.

The Guild also has a monopoly on banking through its Guild Bank, which serves the entire Imperium and uses spice as a unit of value. You can rely on the Guild to never stab you in the back, but any House that tries to screw over the Guild is going to be punished with a series of fees and penalties. Oh, and if you ever find yourself well and truly fucked, with the strength of your House broken and your rivals beating down your door, the Guild maintains the Tupile system as a place of safe exile. Paying the Guild your last bit of cash to live out your days on some faraway planet isn’t great, but it’s better than having your enemies hunt down each and every last one of your family.

The Mentat School trains people to be human computers. Mentats aren’t just people walking around with spreadsheets in their heads; they can actually bring human judgment and intuition to bear on massive amounts of data and predict, for example, that there’s a 79.4% chance that your Bene Gesserit advisor plans to murder you, with an 85.6% chance that she’ll do it by poisoning that Caladanian wine you love so much. The Mentat school isn’t a major political faction, but no House would enter tense negotations without a mentat advisor.

The Swordsmaster’s School of Ginaz was founded to train soldiers to heretofore unseen levels, and many other schools have tried to imitate their success. House Corrino founded the Imperial Suk School to train expert doctors whose “imperial conditioning” prevents them from ever harming their patients. These were just minor plot points in the books, and as such, don’t get a lot of detail here.

Swordsmasters? Well, I see them around in the evenings. What do you want with them?

The Great Houses

Dune: CotI lists over thirty Great Houses in the Landsraad council, but there are only a handful who are major players and get a lot of detail. Each of the Great Houses has a number of Houses Minor united under its banner, too. (Yep, just like Game of Thrones , but with lasers.)

Power accrues to power, and House Corrino still sits on the Golden Lion Throne and remains the most powerful House in the Imperium. The Corrinos are notorious for internal power struggles, but the House as a whole rules with a steady hand, even if its Emperors are not particularly long-lived. They’ve moved their seat of power to the planet Kaidan, after an assassination attempt on the royal family turned their homeworld, Salusa Secundus, into a radioactive wasteland. It now serves as a prison planet, but is secretly the training ground for the Emperor’s matchless Sardaukar troops. The Sardaukar are like nuclear weapons themselves: rarely employed, but their mere existence is sufficient to deter any disobedience.

While the Corrinos have spent thousands of years consolidating wealth and power, the Atreides have shored up their reputation for honor and justice. The Atreides first came to prominence at the Battle of Corrin, when a cowardly Harkonnen abandoned his post and an Atreides swept in to save the day. The Atreides aren’t particularly wealthy, but many of the lesser Houses count on them to take a principled stance in times of crisis, as they did in the Ginaz/Moritani war. Having the support of all these “backbenchers” makes them a threat to the Corrinos and a target for the more devious Houses, but their enemies are afraid to take action against them...openly.

House Harkonnen is a bag of cunts. They were exiled from the Landsraad for their ancestor’s cowardice, but since that time they earned their way back in through a series of shrewd business decisions that cornered the market on several luxury goods, making them too wealthy and powerful to ignore. They’ve even been awarded control of Arrakis, the richest fiefdom in the galaxy, and they’ve ruled it the way they rule every other world under their control: repulsive decadence and brutal exploitation. Their homeworld is an industrialized shithole, and most of their subjects are degraded slaves.

And now we get to the Houses that were just invented for this game! House Wallach was founded by a general loyal to the Corrinos, but while they’re still tight enough with the Emperor to train their heirs on Salusa Secundus, their primary focus is now diplomacy. They also have a strong alliance with the Bene Gesserit, who are headquartered on Wallach IX.

House Moritani is a bunch of devious bastards who are still best known for quickly wiping out House Ginaz in a brief and bloody war of assassins. They’ve spent generations trying to shake their dubious reputation, but retreating into relative obscurity while rumors of a military buildup continue to circulate hasn’t helped them much.

House Tseida developed on a planet which was ruled by a Butlerian Inquisition for thousands of years. Theocracy has waned, but they are, no kidding, a House of expert lawyers. They keep themselves strong (and indispensible) by representing other Houses in business ventures, and they’re strongly intertwined with the Spacing Guild.

Swordsmasters? I think they drink a lot of booze at the bars or someplace.

The Imperium

You’ve been told all sorts of things about all sorts of factions without understanding how they work, haven’t you? I’m sorry, I’m just trying to roughly follow the book here.

The document that guides the way the Imperium works is the Great Convention . It’s essentially the extension of a general truce, and is designed to protect the powerful and prevent open warfare. Basically, it goes lie this:

1. It defines the rights and obligations of Houses, how the Landsraad council works, and other boring stuff that isn’t meant to be spelled out in a space opera novel or a roleplaying game.

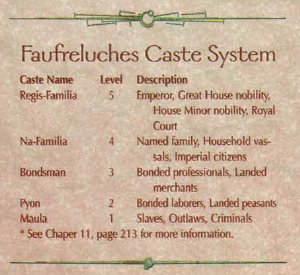

2. It defines the faufreluches, the universal caste system.

3. Houses are allowed to wage war on each other through formal duels, assassination, and political hostage-taking and ransom. This is called kanly. As long as you formally declare your vendetta, almost anything is permissible. What, even knifing babies in the crib? Absolutely. Can I interest you in a long vacation in the scenic Tupile system? By “scenic” I mean only the Spacing Guild knows where it is and you can never return.

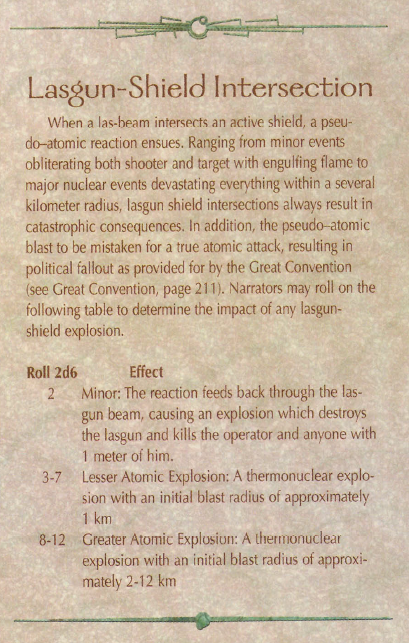

4. One thing that’s not allowed? Atomic weapons. Ever. The penalty for this is that the Emperor executes your entire House and your home planet is destroyed.

The Landsraad is, uh, feudal space Congress. The Emperor is the leader of the council, and while he doesn’t have to do anything he doesn’t want to, he’ll usually follow their recommendations. The Landsraad passes laws, creates and funds Imperial projects, listens to its members whine about how they’re not getting enough stuff, and so on, just like Congress. The Landsraad forbids any action against the Guild, and authorizes the Guild to penalize misbehaving Houses with fines, punitive rates, embargoes, or outright confiscation. Basically, you can’t wage war unless the Landsraad sanctions it. The space knights of the Dune universe don’t fight each other with fleets of X-Wings and Birds of Prey and Flaz Gaz Heat Rays and such because the Guild is having none of that bullshit.

The CHOAM corporation was founded in the Great Convention as a financial reserve for the Imperium, and it’s now the center of the imperial economy. (It stands for Combine Honette Ober Advancer Mercantiles.) It’s deeply intertwined with the Guild Bank and with every commercial enterprise on every planet in the Imperium. Through CHOAM, the Landsraad regulates trade and establishes currency. (The sol, plural solaris, is the imperial unit of currency, and pegged to the value of spice. Ron Paul Muad’Dib, eat your heart out.)

Next time, on Dune : Everything about the Great Houses that you don’t know already.

Great Houses

Original SA post

Chapter 2: Great Houses

This chapter gives an overview of the Landsraad and the most powerful Great Houses. It also contains the rules for creating Houses Minor for the player characters, even before we get rules for creating the PCs themselves! This is intentional. The Dune series is very much about interorganizational rivalry, how people are shaped by the backgrounds, and the historical consequences of individual actions, and so Dune is way serious about playing people with meaningful connections instead of a gang of murderous hobos.

Collectively, the Great Houses are the oldest institution in the Imperium, older than the empery, the Guild, and the Bene Gesserit. Each of the Great Houses holds a siridar -fief over a planet they claim as their homeworld, at least one seat in the Landsraad council, and shares in CHOAM, the corporation which controls the Imperial economy. In return, they’re responsible for paying tithes and conscripts, upholding the Great Convention, and good stewardship of any privileges they’ve received from the emperor or CHOAM--additional fiefs, exclusive contracts, board memberships, etc. These interests are often much more important to a House’s power than the resources on their home planet. Arrakis is, of course, the most valuable fiefdom in the known universe.

(You know how on C-SPAN, Congress spends days arguing about what company in what state will get a contract to build $400 million worth of tanks the Army doesn’t need? Multiply that by 100, and you get the Landsraad and CHOAM. But you don’t have to think about all those excruciating details, because this is a story about psychic kung fu masters having knife-fights in the space desert.)

It’s chilly on Caladan.

A Great House has to uphold the Great Convention on its planetary fiefs, but that’s basic stuff like the caste system, general law and order, and the ban on nuclear weapons. While there’s a courtly, cosmopolitan high society that brings the nobles together, that leaves room for vast differences in their philosophies, which are reflected by even vaster differences in the kind of civilization one encounters from planet to planet. A Great House has free rein to make their homeworld a shining meritocracy, a worldwide slave plantation, or a wretched hive of scum and villainy.

Oh, and about that caste system, it’s called the faufreluches * and it governs Imperial society. At the top are the regis-familia , comprised of the Emperor, his court, and all the nobility of the Great and Minor Houses. Below them are na-familia , “named family,” which mostly includes the vassals and personal entourage of the Houses. Hey, wake up! These are your player characters: the swordmasters, mentats, assassins, and other experts who help a House succeed or fail. Characters from the books like Duncan Idaho and Piter de Vries are na-familia . Below them are merchants, artisans, peasants, slaves, and other people who probably won’t be important characters in a Dune game. Exactly what rights are assigned and denied to each caste is detailed in a later chapter.

*The etymology is beyond me; my best guess is a link to “mamluk.”

There are thousands of Great Houses in the Landsraad to represent the thousands of inhabited planets in the Imperium, but most of them are “backbenchers” who have few representatives and meager CHOAM holdings, and throw their vote behind one of the handful of Houses that are the real heavyweights. (This is not an interpretation I like, but I’ll whine more about that later.) The Emperor isn’t bound by Landsraad decisions, but it’s unwise for him to veto all their decisions with complete abandon. The power players of the Landsraad are listed here along with some of their Houses Minor, their ethos, notable members of their entourage, and their views on the other Houses.

A couple of notes: first, the art representing each house is notably bad. It’s well-executed, but it doesn’t illustrate its subjects with any meaning. Second, I thought I was a feminist, but after going through the House descriptions I realized I hadn’t said anything about sex and gender in Dune. The feudal system, even tens of thousands of years in the future, is patriarchal: only men can officially rule a House. However, the Bene Gesserit is an all-female order that literally controls the breeding of royal bloodlines, and more than one siridar -baron has had his own name fade from history because the BG decided he should only sire daughters to be absorbed by another bloodline with compatible genes.

Did you notice my just and honorable stubble?

The Atreides are the siridar -dukes of planet Caladan, an agricultural world known for really good wine. They’re supposedly descended from the mythical Atreus, but their reputation for leadership, courage, and morality is not in dispute. These guys are, like, the Gryffindor of Dune. They’re not a very rich House, but their insistence on just government gets a lot of other Houses to rally behind their political stance.

The Atreides are currently led by Duke Leto Atreides, and his entourage is an all-star team: Thufir Hawat (spymaster and mentat), Warmaster Gurney Halleck (best swordsman ever), swordsmaster Duncan Idaho (second-best swordsman ever), Dr. Yueh (Suk doctor), his concubine Lady Jessica (BG agent), and his son Paul, who was educated by all of these frighteningly competent people.

The Atreides respect the Corrinos while calling for reform, believe the Moritani are corrupt pawns, admire the Tseida and the Wallach, and would like to see all the Harkonnens put down like the venal beasts they are. Atreides Houses Minor include the Demios, Parthenope, and Spiridon.

You bought the Golden Lion Throne from Halloween Express?

The Padishah Emperors of House Corrino still rule the new Imperium they founded about 10,000 years ago. They rule by the maxim that “law is the ultimate science” meaning they’re the most Machiavellian motherfuckers around. You could also say they live by the policy “speak softly and carry a big stick,” because while they prefer to quell discontent with patient diplomacy, their benevolence always carries the implied threat of their unbeatable Sardakuar troops, which they employ only as a last resort. The responsibility of the Golden Lion Throne means that the emperor often has to put the interests of the Landsraad above taking as much as he can for himself, so the Corrinos have to deal with more grumbling from their Houses Minor than any other Great House. There’s a reason why House Corrino endures while its emperors aren’t particularly long-lived.

The current Padishah Emperor is Shaddam IV, whose father, by the way, died from poisoning. His closest advisors include Count Hasimir Fenring, a swordmaster and prodigy of the BG breeding program; Lady Margot, Fenring’s wife and a Bene Gesserit; Gaius Helen Mohiam, his Truthsayer and a Bene Gesserit Reverend Mother, and his five daughters.

The Corrinos admire the Atreides, but consider them enemies. They consider the Harkonnen useful if unreliable pawns, and the Moritani as more reliable pawns. They see the Wallachs as a House they can manipulate. Despite the Tseidas’ reputation for fairness, the Corrinos think of them...well, the way most people think of an organization of lawyers. Corrino Houses Minor include the Aingeru, Evangelos, and Schiavonna.

Baron Harkonnen: Fat.

House Harkonnen was exiled from the Landsraad at its inception, but earned its way back in through a series of business deals so shrewd, and so lucrative, that they eventually not only regained their siridar -barony but forced the other Great Houses to grudgingly award them the fiefdom of Arrakis. So this makes them the scrappy underdog who overcame the odds, right? No. Think more like if Joffrey Baratheon had Draco Malfoy’s baby. From their polluted homeworld of Giedi Prime, the Harkonnens rule a commercial empire based on ruthless exploitation, dehumanizing slavery, and sickening decadence. They’re feared and loathed for their hideous riches and hideous practices, and the Harkonnens, in turn, seem to enjoy being hated by those they consider their natural prey.

The Harkonnen are currently led by Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, a brilliant and megalomaniacal tyrant. He has no heir, probably owing to the fact that he’s a morbidly obese pedophile. His closest advisor is a psychopathic mentat-assassin named Piter de Vries. He’s also supported by his possible heirs, Glossu Rabban, best known for murdering his own father with his bare hands, and Feyd-Rautha, best known for being portrayed by Sting in tiny shiny panties.

The Harkonnens want to kill all the Atreides. Painfully. They conspire with the Corrinos to remove the Atreides, but of course they plan to betray him. They consider the Moritani allies, believing that their vision is limited. They’re suspicious of the Tseida, and hate the Wallachs for supporting the Atreides. Harkonnen Houses Minor include the Ivilonette, Ruymandiaz, and Truscantos.

The Moritani got their fief by guarding Buckingham Palace, I suppose.

Now we get to the Houses that were created for this game! First on deck, the Moritani are descended from an ancient order of assassins. They reached a crisis point when House Ginaz unsuccessfully tried to indict their House for using a fake Suk doctor to assassinate the members of House D’artanna. The Emperor sanctioned a War of Assassins, and the Moritani soon elicited a response along the lines of “Holy fucking shit” for wiping out House Ginaz, known for producing the best swordmasters in the universe, in record time.

That said, the Moritani don’t seem so bad. Now that they have undisputed control over their home planet of Grumman, they’re mainly focused on putting their house in order, no pun intended. They’re trying to shake their reputation as an assassin cult, but their decision to withdraw from the public eye while they focus on internal development has worked against that effort. Their economic development is accompanied by military buildup, but it seems to be focused on internal security.

The leader of the Moritani is technically Count Ferdinand, but he’s succumbed to dementia and is essentially locked away while his son, na-Count Tycho di Moritani, rules as regent. He’s advised by Delbreth Umbrico, a Swordmaster-Mentat, and his mother Lady Redolyn, a Bene Gesserit trainee. Tycho has his own appointed advisor, a “tall, swarthy monolith” named Pradisek, who probably wears a turban and calls himself a vizier. Tycho also has two sisters who are all too aware that if anything happens to Tycho, one of them could birth the Moritani heir.

The Moritani regard the Atreides as “friends of our enemies.” They’re grateful to the Emperor for allowing their revenge, but that doesn’t mean they’re dumb enough to trust him. They look for ways to manipulate the Harkonnens and the Wallach, and they’re on friendly terms with the Tseida, whom they trust to represent them. Moritani Houses Minor include the Laurentii, Kazimierz, and Prinzporio, all of which are renowned for being difficult to type.

I’m Leonard J. Crabs, and I approve this box of flashing shapes and colors.

House Tseida is also called the House of the Phoenix, and they’re a weird bird. The House actually evolved out of a highly bureaucratic theocracy which enforced the Butlerian prohibitions with extreme prejudice, and emerged as a Great House with the help of the then-Emperor and the Spacing Guild. They are, to put it bluntly, a House comprised of lawyers, who transformed their ancient bureaucracy into a service-based economy centered on legal services. If you’re a badass Swordmaster Assassin but today you have to attend a CHOAM board meeting to argue over all that boring C-SPAN bullshit I warned you about, you want to hire a Tseida diplomat. Otherwise the Harkonnens will sue the space-pants off of you and you’ll have no place to hide your space-daggers. The Tseida have strong ties with the Spacing Guild, from whom they learned to develop a facade of political neutrality. Well, in fact they do seem to be politically neutral on issues besides “We should make shit-tons of spice-dollars.”

The Tseida are currently ruled by the Marquise Catriona Tseida, who acts as regent until her nephew Iorgu is of legal age. She is advised by her mother Ilema (who is a Bene Gesserit like all the other politically powerful moms), a Mentat-Suk named Dorian Mu, and Hiro Okusa, a crotchety Swordmaster who carries around a blunt kendo stick to beat people with. Iorgu is being trained by all these people as well as his aunt Catriona, who helps him spy on court affairs.

The Tseida are on friendly terms with the Atreides and Wallach. All their interactions with the Moritani come with a “don’t blame us, we’re just their lawyers” disclaimer. They’re on good terms with the Emperor but don’t like him meddling in their affairs, and dislike the Harkonnen propensity for slippery legal schemes. Tseida Houses Minor include the Ikeni, Sunnivas, and Wyrkiru.

The Moritani assassins are no match for our SCUBA LASERS!

House Wallach is relatively young at only 5,000 years old, but they were founded by an extraordinarily loyal and successful Imperial general. Their founder, Maximillian Banarc, was so grateful to receive the fiefdom of Wallach VII that he named his newfound House after it. The Wallachs have mellowed to become a House of even-tempered scholar-soldiers, but their military tradition (and their ties to the Emperor) remain strong enough that they send their scions to be trained on Salusa Secundus. They also benefit from a close, mysterious relationship with the Bene Gesserit, who accepted the offer to headquarter their order on Wallach IX.

The leader of the Wallachs is Baron Wolfram von Wallach, a contemplative old soldier who, when not practicing statecraft, spends his time writing his memoirs and beating up his soldiers three at a time. Gotta keep fit, you know. The old general has sired many children, but currently claims Christhaad von Silgaimar as his only heir. His entourage includes his concubine, Lady Gersha, who is the mother of his son and a very gifted architect. Ha ha, just kidding, she’s a Bene Gesserit. He also has Olifer Mangrove, a Mentat with a silly name.

The Wallachs are decent guys, all told. They’re friendly to the Atreides and the Corrino, cordial with the Tseida, and they despise the Harkonnen and the Moritani. Wallach Houses Minor include the Brugge, Ottovaar, and Roinesprit.

House Minor Creation

Houses Minor are lesser branches of a Great House who manage regions of the parent House’s homeworld and/or subsidiaries of their CHOAM interests. They answer to the planetary law of their homeworld, and form a planetary “Sysselraad” that answers to their parent House. And, of course, they squabble among themselves for a greater share of the power, wealth, and influence controlled by the Great House that spawned them.

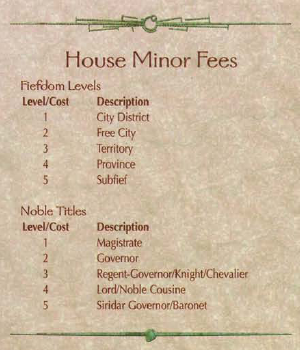

The rules for House Minor creation are pretty simple, and really aren’t hampered by not having created characters or seen the rules for using the House traits yet. They are hampered by being haphazardly explained. A House Minor has 8 traits. First is Holdings, consisting of Fiefdom and Title, both rated 1-5. Then comes Renown and Assets, which are rated differently. Last are the four House Attributes, also rated 1-5, and each of which includes two sub-attributes, or edges.

Fiefdom determines the size of your fief, from a city district to a continental “subfief.”

Title is the rank of the head of your House, ranging from magistrate to Baron. What’s the value of being a Baron rather than a Magistrate? Unexplained!

Renown is your House’s fame and prestige. It affects your interactions with other Houses, including a roll just to see if anyone’s even heard of you. Renown starts at 1, and can’t be increased at creation.

Assets covers anything you can leverage to succeed in a venture, including not only cash, but things like favours from Guild bureaucrats and expendable sleeper agents. We’ll use these to initiate “House Ventures” during downtime between sessions. Assets starts at 10, and will fluctuate up and down depending on our success.

Status is your “privilege and favour” with your governing Great House, and determines your ability to undermine rival Houses Minor or get support for your ventures from your Great House. Status is divided between Aegis and Favour , which are not explained.

Wealth measures your overall financial resources, including cash, revenues, investments, infrastructure, contracts, everything. It’s divided between Holdings and Stockpiles , again unexplained.

Influence is your political sway among both fellow nobles and your subjects. It’s divided between Authority and Popularity which are unexplained but at least fairly self-explanatory.

Security is the power of your army and your intelligence network. It’s divided between Military and Intelligence , also unexplained, but also self-explanatory.

Creating a House is actually pretty easy. After choosing a Great House, a name, and a rough idea of your background, you pick from one of several archetypes, which gives you a package of Attributes. Then you get 15 development points to spend. Fief and Title are purchased up from 0 on a one-for-one basis. Increasing an Attribute costs five points, while increasing an Edge costs 3 points. (It appears your Edges can be +/-1 of the base Attribute.) Any leftovers go into your Assets.

House Defender : Champions the Great House philosophy and defends them at personal cost. Status 3, Wealth 2, Influence 2, Security 3 (Military +1)

House Favourite : Implements Great House policy with great enthusiasm, supporting the status quo and earning political favor. Status 3 (Favor +1), Wealth 2, Influence 3 (Popularity -1), Security 2.

House Pretender : Goes along with the current political trends, hoping to replace the ruling House if the line should fail. Status 2 (Favor -1), Wealth 3 (Holdings +1), Influence 3 (Popularity +1, Authority -1), Security 2.

House Pawn : Slavishly supports the Great House, hoping to earn favour through unwavering support. Status 4 (Aegis +1), Wealth 2, Influence 2 (Popularity -1), Security 1.

House Reformer : Supports reform out of a genuine belief in changing things for the better. Status 2 (Favor -1), Wealth 2 (Stockpiles -1), Influence 3 (Popularity +1, Authority +1), Security 3.

House Sleeper : Secretly supports another Great House, undermining its parent House from within. Status 2, Wealth 3 (Stockpiles +1), Influence 2 (Authority -1, Popularity -1), Security 3 (Intelligence +1).

So, uh, how is it possible to have both edges at +1 or -1? Can you take a -1 to get points to spend elsewhere? What’s the difference between Status 2 (Favor -1) and Status 1 (Aegis +1)? I have no fucking idea.

Setting the mechanics aside, I really don't like this interpretation of how Houses Minor work. It's canon that there are many inhabited worlds in the Imperium and each Great House has a homeworld, but not, if I recall, that almost every inhabitable planet has a Great House or that Houses Minor are bound to their patron's homeworld, especially when the degree of their nobility ranges down to being magistrates of city districts. So there are thousands of Great Houses, only a handful of whom really matter, but all of them and their extended families are part of the highest caste? If I can be a distant relative of the Emperor and just be a civil servant in Space Pittsburgh? What does that mean for the Houses Minor of one of a thousand insignificant Great Houses? The ostensible purpose of these assumptions is to allow the PCs leeway to adventure all over the Imperium--even in the book, Duke Leto spends a lot of time in meetings--but I think the purpose would have been served just as well by saying that the Houses Minor govern planets or companies of their own.

Houses Minor are the nadir of Imperial nobility, but they're still wealthy beyond the dreams of the common people, and they more-or-less conduct themselves like miniature versions of the Great Houses. They have to steward their resources shrewdly or come to ruin, and a lot of that responsibility falls upon the House Vassals, the royal entourage of experts who are situated below the regis-familia and above whole agencies of professionals, soldiers, and laborers. The nobles and the House Vassals are the PCs.

There are three basic divisions of a House’s administration. Honestly, they give you more detail than necessary, but it’s useful for players who want to know where they fit into the House and ignorable for those who don’t. First is House Affairs , which covers fief government, representation in the Sysselraad, and managing the royal household and their retainers. The first two are boring C-SPAN crap, but the last is about making sure your kitchen staff don’t poison your Caladanian wine and your valet doesn’t plant a killer drone in the nursery. (I really, really wish they’d just state this bluntly, but that’s why Houses are riddled with Bene Gesserit although it’s an open secret they have agendas of their own. The BG is a clan of lady space ninjas. You’re a noble in a Byzantine space empire where cold-blooded murder is legal and your enemies want to knife your heirs in their cribs. Solution? Marry a lady space ninja.)

Mercantile Enterprises is straightforward. Managing agriculture, mining, manufacturing, service-based industries, managing CHOAM holdings, paying tithes to your Great House, meeting production quotas, more C-SPAN crap.

Household Security , ooh, that’s the good stuff. This overlaps with House Affairs, since it covers both military and intelligence operations ranging from your Warmaster conducting full-scale land war all the way down to your Swordmaster training your personal bodyguard. Houses Minor only rarely declare war on each other, but they do sometimes have to quell rebellion. Intelligence networks, on the other hand, are needed by every House, managed by Spymasters and Masters of Assassins.

Next time, on Dune : Swordmaster 4/Mentat 3/Assassin 3/Arcane Archer 5

Character Creation

Original SA post

Chapter 3: Character Creation

This has been too long in coming, so here's a link to the last chapter.

Dune’s character creation sets out with advice on fleshing out a character concept and seeing PCs as more than the sum of their stats. It also devotes a lot of space to telling the GM and the players to be cool with each other, and to buy in to the basic premise of the game and its setting. That is, the PCs are going to play a House entourage, so they have to be able to get along. For example, Suk doctors are conditioned to be nonviolent, but a Suk PC who constantly rails against his House’s military endeavours is inappropriate. That is a misinterpretation of the setting, but the real reason it’s a bad idea is that it will lead to the players getting on each other’s nerves. What? Gaming advice from adults, for adults? In the 90s, no less?

Players are encouraged to pursue unconventional character concepts; for example, there’s no reason you can’t play a Mentat who is also a passionate duelist, since the source novels are full of that kind of thing. However, there are also some firm limits. First, the Imperium is deeply patriarchal, so men can’t be Bene Gesserit agents, and women can’t inherit leadership of a House. The fact that you’re assumed to be playing a House entourage also discourages you from playing characters who are part of the setting but who aren’t tied to the feudal system, such as a Guild navigator or a spice smuggler. However, there are suggestions on how to include such characters as a “special guest appearance,” somebody’s secondary PC, or as a character on a long-term mission with a good reason to be palling around with a House entourage.

There’s no advice on how the players reach a consensus on what Great House lineage to play, which is a glaring omission. The House you play will not only have a great influence on the tone of the game, it determines your base stats! Granted, the differences are mostly minor: a +1 to an Attribute edge here, a skill there. But if you’re playing a Mentat, you probably wanted the Tseida’s +1 to Intellect (Logic) instead of the Harkonnen bonus to Physique (Strength). I’m guessing the Baron makes all his young relatives pump iron while he watches.

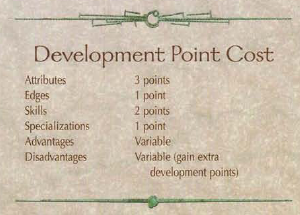

The default character creation method boils down to choosing a series of “packages,” starting with your House Allegiance, with a few free Development Points at the end for additional customization. At each stage of creation, all the packages are worth the same amount of points, so if none of them appeal to you, you can just take some free points. You can also do full point-buy with 130 Development Points.

I can’t explain the character creation process in full without going into some detail about the traits themselves. A Dune character sheet will be familiar to anyone who’s ever played a Storyteller, Unisystem, or D6 game, not to mention many others. Player characters have Attributes, Skills, and Traits.

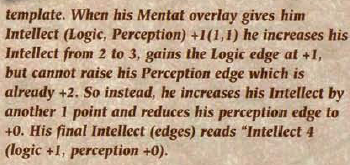

Attributes are rated 1-6, with 6 representing the absolute peak of human potential. Each Attribute is also split into two Edges, just like the House Attributes from the previous chapter.

So it’s possible to have Physique 2 (Strength +1). I really don’t like this, because it seems to defeat the point of the laudable design decision to combine Strength and Constitution in the first place. Too many other games have a Strength attribute that falls by the wayside and is almost useless both in and out of combat. (I’m looking at you, White Wolf.) Second, you need to keep track of the Edge bonuses you get during character creation. If a bonus would give you +3 in an Edge, instead you “reset” and increase the base Attribute by 1. Oh, and what’s the difference between having Physique 2 (Strength +1, Constitution +1) and having Physique 3? I have no idea; I hope they’ll explain later.

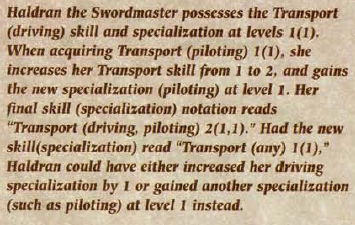

Oh! How very simple!

Skills, on the other hand...I like what they did here. First, there’s a bounded number of skills, and they’re appropriately broad. “Armed Combat,” for example, covers all melee weapons. Many skills do require a specialization, but there’s a limited number of those, too, and your base rating still reflects general knowledge. A character with Science 2 (Biology 1) specializes in biology, but has an education in all the physical and life sciences, while a character with Transport 1 can operate everything from a car to a space shuttle. So Dune avoids the pitfalls of a game with extremely specific skills and a potentially infinite number of skills for things like academic disciplines, and prevents PCs from being so specialized that their skills are often irrelevant.

Traits are miscellaneous advantages and disadvantages that include mundane resources, social statuses, strengths and weaknesses of character, and “conditioning” that isn’t covered by skills, such as that of Bene Gesserit agents and Suk doctors.

Having dispensed with those details, these are the stages of character creation:

Stage 1, House Allegiance , is the Great House to which your character’s House Minor belongs. It determines your base attributes, plus some skills and low-level Traits. All the Houses get base Attributes of 2 with a bonus here and there, plus a point of Culture, History, and World Knowledge with a free specialization in your native House and homeworld.

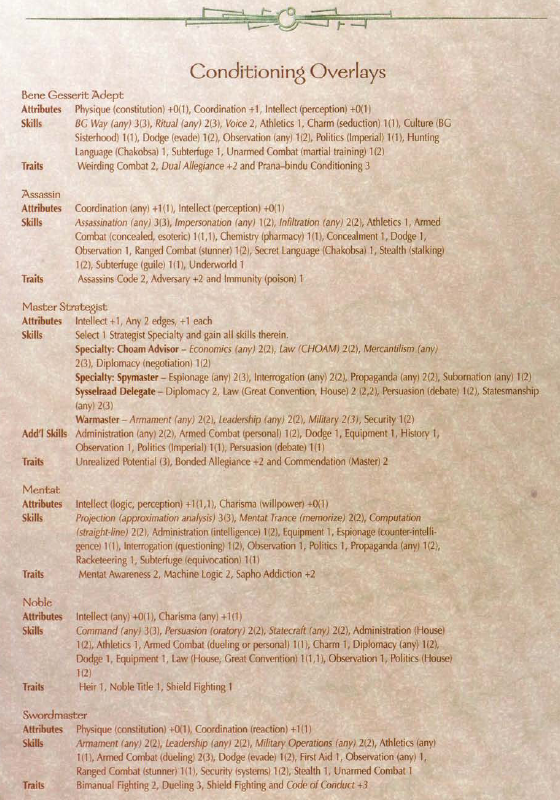

Stage 2, Vocational Conditioning , basically means character class, like Bene Gesserit Adept, Strategist, Assassin, et cetera. These packages grant attribute bonuses, more skills, and Traits related to your character’s profession and conditioning. While Dune isn’t a class/level game, some of the “vocational” Traits are exclusive and integral from a setting point of view. Mentats, for instance, must be trained from early childhood. Vocation is also important because it determines your caste.

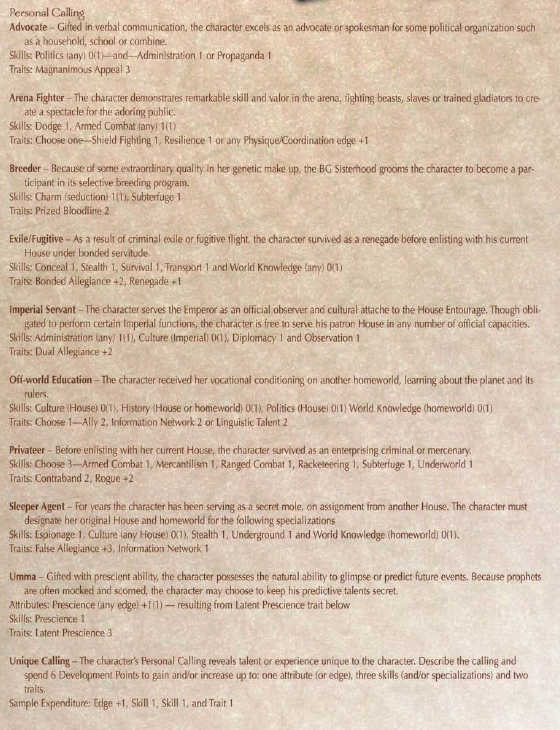

Stage 3, Background History , encompasses three background packages that represent your character’s upbringing, career, and goals.

Early Life is a good opportunity for a character to either become more specialized or get some “multiclass” training with backgrounds like Mentat Priming, Bene Gesserit Teaching, or Dueling Instruction. (Paul Atreides got all three.)

House Service goes beyond your profession to your actual job--what do you do for your House? Suk characters are likely to take House Physician, but a Swordmaster could potentially be a Security Commander, Weapons Master, or the Personal Confidante to the royal heir.

Personal Calling is essentially what marks you out as unique. The term is imprecise, because the packages encompass a mixture of career paths and unusual backgrounds. For example, you could be a Sleeper Agent or an Arena Fighter, by choice or otherwise, or maybe you received an Off-World Education, which is a circumstance of your upbringing. Or you might be a Breeder, which is exactly as creepy as it sounds--it means that because of some genetic quirk, the Bene Gesserit take a special interest in you as part of their grand scheme to control the bloodlines of the Houses.

Stage 4, Finishing Touches , gives you five “freebie” points to spend.

Development Points

At this point, your Vocational Conditioning will determine your social Caste and starting equipment. Each character also gets 3 Karama (“karma points” to spend on automatic successes), and Renown. Renown has 4 aspects: Valor, Learning, Justice, and Prayer, representing a character’s reputation for heroism, knowledge, diplomacy, and wisdom, respectively. You get 1 point to put in 1 aspect, plus any granted by the packages you chose.

That's it! The GM has veto on character concepts that make no sense, like a dueling Suk doctor. There is some more advice here that strikes me as too heavy-handed: case in point, the assertion that a Noble would never have the Assassination skill, despite the fact that the Emperor's best buddy is duelist, an assassin, and an all-around treacherous bastard.

”I can’t eat fifteen gallons of spice!”

“Oh, it’s not going in that end, Mr. Atreides.”

Next time, on Dune : I'll go over the sample characters, and create a couple myself.

Character Creation Part 2: How to Succeed in Kanly without really trying

Original SA post

Chapter 3, Part 2: How to Succeed in Kanly without really trying

I don’t think you can really grasp how a game handles characters by just reading through its character creation chapter, so I am making a couple of Dune characters. However, I am creating these characters before going through the next chapter, which details all of the traits and what they do.

Herbert wanted to portray a far future in which cultures from our history had synthesized beyond our imagining, so the Atreides entourage features characters with names like Duncan Idaho, Thufir Hawat, and Wellington Yueh. True to form, my characters have randomly generated and mismatched names.

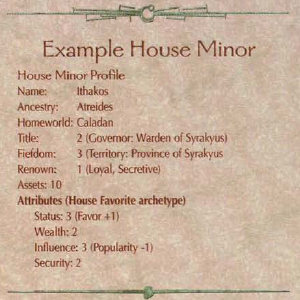

House Minor Creation

First, we will generate a House Minor! The Imperium is a huge Byzantine space empire of intrigue, treachery, and naked greed, so what better choice than the most Machiavellian and Shakespearean House, the Moritani ? The name of our House Minor is Mori, which is a coincidence. It came up as a randomly generated name for one of our characters, and true to Dune’s ethos, I like that it is ambiguously both Italian and Japanese.

House Mori is an ancient distaff line of the Moritani. Publicly, they’re very much onboard with the new Moritani way, leaving behind their history of treachery in order to focus on economic expansion. Privately, they’re well aware that the Count’s household is a mess, and not content to hope and pray that things will work out. They’re securing their holdings and long-term investments against misfortune, and cultivating their intelligence assets against infiltration by other Houses. Based on this backstory I just made up, I’ll pick the House Pretender archetype--a House that goes along with popular political trends, tries to expand its influence, and is poised to take over the Great House’s title if it collapses. That gives us these stats:

quote:

Status: 2

Wealth: 3 (Holdings +1)

Influence: 3 (Popularity +1, Authority -1)

Security: 2

Renown: 1

Assets: 10

We have 15 Development points with which to purchase a title, a fiefdom, and to improve these stats. (5 points per Attribute, 3 points per edge, Renown starts at 1 and can’t be raised, while leftovers go into Assets.) It doesn’t explain to us why it’s better, mechanically, to be a lord rather than a lowly magistrate, or to control an entire province instead of a city. It also still doesn’t explicitly define the Attribute edges, and skimming the later chapters hasn’t helped me. Oh, well. Spending my points, I get these final stats for my House Minor:

quote:

Name: Mori

Ancestry: Moritani

Homeworld: Grumman

Title: 4 (Lord Duke)

Fiefdom: 2 (The Free City of Ravanna)

Renown: 1

Assets: 10

Status: 2

Wealth: 3 (Holdings +2)

Influence: 3 (Popularity +1)

Security: 2 (Intelligence +1)

House Mori holds a grand title, but doesn’t control much physical territory--clearly we are all about the service-based economy. We’re rich as shit, politically influential, and we have a great intelligence network, which is good--our Great House betters aren’t especially fond of us. Now, on to creating actual characters.

Character Creation

Malik Richmond was born into a family that has spent generations serving as personal security to the Mori household. His forward-thinking parents had him trained as a Mentat, believing that a well-rounded advisor could accrue more influence with the nobility than his family had in the past. Malik, however, realized that he still needed credibility as a military man, and devoted himself to becoming a fearsome duelist. (Mentats are cool, and sword fights are cool. That’s as much thought as I put into this decision.) Malik has the following background packages:

Allegiance: Moritani

Conditioning Overlay: Mentat

Early Life: Dueling Instruction

House Service: Security Commander

Personal Calling: Arena Fighter

You can refer to my last update to see the charts of background packages and the stats they confer. Adding it all up, we get this:

Captain Malik Richmond posted:

Attributes:

Physique 2

Coordination 2 (Reaction +2)

Intellect 3 (Logic +1, Perception +2)

Charisma 2 (Willpower +1)

Prescience 0

Skills:

Administration 1 (Intelligence 2)

Armed Combat 2 (Dueling Arms 2)

Computation 2 (Straight-Line 2)

Culture 1 (Moritani 2)

Dodge 2

Equipment 1

Espionage 1 (Counter-Intelligence 1)

History 1 (Moritani 1)

Hunting Language 1 (Bhotani Jib 1)

Interrogation 2 (Questioning 2)

Mentat Trance 2 (Memorize 2)

Observation 3 (Inspection 1)

Politics 1

Propaganda 1 ( Misinformation 2)

Projection 3 (Approximation Analysis 3)

Racketeering 1

Ranged Combat 1 (Stunner 1)

Security 1 (Surveillance 1)

Subterfuge 2 (Mind Games 1, Equivocation 1)

World Knowledge 1 (Grumman 1)

Traits:

Alertness 1, Dueling 2, Commendation 1, Mentat Awareness 2, Machine Logic 2, Sapho Addiction -2, Shield Fighting 1

Renown: Valor 1

Caste: 3 (Bondsman)

Karama: 3

Equipment: House uniform, ComNet transmitter, Knife, Needlegun, Solido projector, Solido recorder, Shigaware reels

Wow, that’s a lot of stuff! And I still have 5 free points to spend, plus any I gain from taking Disadvantages. Attributes are expensive. Skills are almost as expensive, and therefore a sucker’s choice. Instead, I’ll plow it all into advantages. I take Information Network at 2 points and Compounded of Whispers for 3 points. I’ll also take a 2-point Adversary. This nets me 2 more points, which I’ll spend to add 1 point to my Commendation and Information Network advantages by one. We also get to put a point in one category of Renown, and our Conditioning determines our caste and our starting equipment.

Malik’s Commendation represents a captaincy in Mori military intelligence. His top-notch Information Network consists of both merchants connected to the Moris’ economic interests and old-school spooks who like the cut of his Bhotani Jib.

Now for a very different type of character, Sofia Mori . Although she is part of the noble household, Sofia was an orphaned cousin, and have been overlooked and ignored if the Bene Gesserit sisterhood hadn’t seen something special in her. When the family offered up its daughters to be trained in the BG Way, Sofia was the one they wanted. She’s returned to the service of her own House to protect and educate her young relatives, while also advocating for Mori political interests. Sofia has the following background packages:

Allegiance: Moritani

Conditioning Overlay: Bene Gesserit Adept

Early Life: Noble Household

House Service: Diplomatic Spokesman

Personal Calling: Advocate

As with Malik, I just chose the packages that made sense for the character. It results in a much more focused skillset:

Lady Sofia Mori posted:

Attributes:

Physique 2 (Constitution +1)

Coordination 3 (Reaction +1)

Intellect 3 (Perception +2)

Charisma 3 (Presence +1)

Prescience 0

Administration 1

Athletics 1

BG Way 3 (Petit Betrayals 3)

Charm 1 (Seduction 1)

Culture 2 (BG Sisterhood 1, Moritani 1)

Diplomacy 2

Dodge 1 (Evade 2)

History 1 (Moritani 1)

Hunting Language 1 (Bhotani Jib 1, Chakobsa 1)

Law 1

Observation 1 (Study 2)

Politics 5 (Imperial 1, Moritani 1)

Propaganda 1

Ritual 2 (any 3)

Subterfuge 2 (Perjury 1)

Unarmed Combat 1 (Martial Training 2)

Voice 2

World Knowledge 1 (Grumman 1)

Traits: Alertness 1, Ally 2, Dual Allegiance -2, Magnanimous Appeal 3, Patron 2, Prana-bindu Conditioning 3, Weirding Combat 2

Renown: Justice 1

Caste: 4 (na-Familia)

Karama: 3

Equipment: House uniform, ComNet transmitter, Knife, BG filmbooks, BG robes

Sofia gets so many Politics specializations that I was able to increase the base trait to 5, making her a political genius. She also has a powerful ally (a Guild banker, let’s say) and a powerful Patron (a wise old Bene Gesserit sister). Her free points are spent on being Highborn (3) and part of a Prized Bloodline (2).

You’ve probably noticed that, while Dune works on a pretty simple Attribute+Skill system, it has a ton of skills, buries your PC in specializations, and has a lot of skills and traits that seem esoteric or highly situational. You’re right! I will mill through them in the next chapter.

That’s how you create Dune characters from scratch.

It's settled. We'll run this shit in FATE next time.

Archetypes

If assigning points to Observation 2 (Head Games 2, Peculiar Odors 3) is too much for you, you can grab one of the pre-generated characters and add your five free points. Bang, done. Some of them have a much more focused skillset than if you picked packages on a makes-sense basis, while others are spread just as thin as the made-from-scratch characters, with heaps of Skill 1 (Specialization 1)

We're not bald. Seriously, read the goddamn book. First chapter, first page.

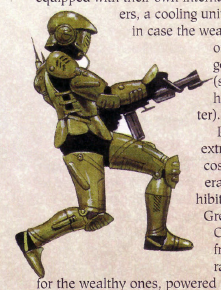

House Adept: The Bene Gesserit sister protects the family that she serves while inspiring a mixture of fear and respect among virtually everyone. Although the BG are famed for their secret knowledge, the Adept’s strength is a combination of social skills and hand-to-hand combat prowess. Adepts aren’t meant to be fighting duels, but they can kick you in the spine through your stomach.

Did they pay Dourif for his likeness? Because come on.

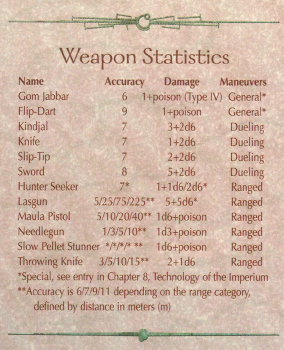

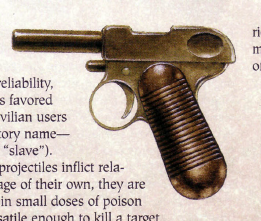

House Assassin: In a universe of devious killers, the Assassins specialty is not so much in killing but in getting away with it. Although he’s not to be taken lightly in face-to-face combat, the Assassin is much more likely to kill you with a drone, or a dose of poison, or a drone covered in poison. Mechanically, this archetype is focused on knowledge and technical skills, with a dash of combat. The best part is the gear: flip-dart, hunter-seeker, maula pistol, shigawire garrotte, slip-tip, French tickler, black mambo, and other silly-sounding ways to kill people.

Maybe I should buy some old tab collars (Welcome back to the Butlerian Jihad)

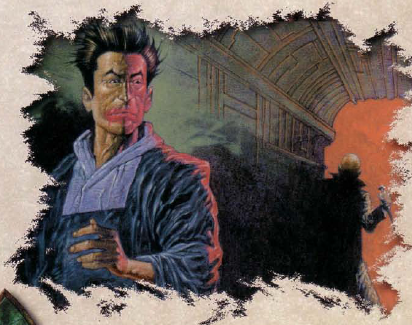

Master Strategist : Strategist is a fairly generic title that doesn’t have the wow-factor of a swordmaster or a Bene Gesserit agent. On the other hand, there’s no doubt about what this guy actually does: lots of social and political skills. Still, as a Dune fan, I’d never play this guy instead of a Mentat.

Baron, I calculate a 93.2% I am the smuggest motherfucker here.

House Mentat: This Archetype assumes that you want to play a spymaster like Thufir Hawat, as opposed to an academic or a guy who is a glorified tax lawyer. A mixture of knowledge and skulduggery, that’s the Mentat. As you saw in my character creation example, the Mentat has some specialized skills that only they can ever have, like “Mentat Trance” and “Computation” which we’ll get into later.

My house has fig-leafed in photographs for untold millennia.

House Noble: It’s good to be the king. The Noble is the only Conditioning that has Caste 5, the royal class of Imperial society. The Noble’s skillset is a combination of diplomatic and dueling skills, which says a lot about the setting.

Do you see this bullshit? This is worse than the prop from Lynch's film.

House Swordmaster: Although he has some military intelligence skills, the Swordmaster’s thing is that he is a straight-up badass. Plenty of points in hand-to-hand and ranged combat skills, plus the Traits necessary to be a great duelist. The Swordmaster allows his Noble boss to say “I can see your point, but on the other hand, what if my buddy just stabs you to death?”

House Suk: The Suk is a deceptively diverse character class. Yes, he heals people, and he even has a built-in Disadvantage that forces him to be a pacifist. But his medical skills also make him a skilled (if scrupulously ethical) psychologist and interrogator.

Next time, on Dune : Those many strange and wonderful Characteristics.

The Explaining of the Characteristics

Original SA post

Chapter 4: The Explaining of the Characteristics

Grave this on your memory, lad: A world is supported by four things… ” She held up four big-knuckled fingers. “…the learning of the wise, the justice of the great, the prayers of the righteous and the valor of the brave. But all of these are as nothing… ” She closed her fingers into a fist. “…without a ruler who knows the art of ruling. Make that the science of your tradition!”

This chapter explains the meaning and use of the Attributes, Skills, and Traits. As I’ve said before, Dune is a fairly simple Attribute+Skill system with advantages and disadvantages, but it complicates itself with sub-attributes, skill specializations, and traits that are very vague.

Skills and traits are also poetically divided into “Learning of the Wise,” “Justice of the Great,” “Prayers of the Righteous,” and “Valor of the Brave” categories.

If this doesn’t work out, can I be an Unhallowed Metropolis character instead? I have my own mask.

Attributes

There are 5 Attributes, rated from 1-5. Each Attribute is also divided into two “edges,” and edges can be +1 or +2 above the base attribute. For example, an especially healthy, if not muscular Swordmaster might have Physique 2 (Constitution +1).

Physique (Strength, Constitution): Dune wisely rolls D&D’s Strength and Constitution into one Attribute. Physique is only used for 3 skills, but Strength is vital to attacking in melee combat while Constitution determines your resistance to injury, illness, poison, and the elements, which are all salient threats on worlds like Arrakis. As an aside, tying melee attacks to Strength is good for game balance, but seems specious in a setting where hand-to-hand combat is almost always fought with knives and relies on expert timing.

Coordination (Dexterity, Reaction): The physical finesse Attribute. Dexterity measures motor coordination while Reaction measures quick reaction times, but the difference between the two is a little blurry. The practical difference is that Dexterity is used for ranged attacks while Reaction is used for all kinds of dodging and parrying.

Intellect (Logic, Perception): Covering intelligence, reasoning, and attention to detail, Intellect is obviously the most important attribute if you want to be good at doing...almost everything that isn’t combat. Out of 60 skills, 39 are tied to Intellect. It’s divided into Logic, for problem-solving and deductive reasoning, and Perception, for general and situational awareness. Have fun arguing with the Narrator over which one applies to the situation at hand.

Charisma (Presence, Willpower): This measures overall force of personality. While Intellect can inform a course of action, you need Charisma to lead and negotiate. Presence measures the ability to influence and evoke emotions in others while Willpower measures not only the resistance to the same, but the ability to bluntly impose your will on others. In some cases there seems to be little rhyme or reason in which edge covers which skill.

Prescience (Sight, Vision) is a special Attribute because most characters will simply have a 0 rating. Simply put, it measures the ability to predict the future. It’s difficult to describe how Prescience works in Dune without getting deeply into the setting, and the books devote long passages to not just explaining how it works, but musing on the nature of time and the limitations of human foresight. Practically, prescients can foresee important events in many possible variations, often in the form of fragments, metaphors, and symbols. Sight measures the scope and depth of your foresight, and Vision measures the ability to interpret them.

Before we go any further, did everyone remember to put points in Assassination, Concealment, Espionage, Infiltration, Sabotage, Security, and Stealth?

Skills

I extend Dune some credit when it comes to its skill system because I’ve seen games do far worse. TORG and Cthulhutech are games that exemplify the two problems I see most often in RPG skill lists: first, the skill list is too long, too specific, and with too much overlap, so that players have to spend lots of points to be able to reliably fulfill a role in the party. Second, they handle academic expertise as a set of skill groups with potentially infinite subskills. Dune avoids the latter by having a bounded skill list, but it’s very guilty of the former.

Dune also has several Conditioning-related skills with very little guidance on how they fit into the game. In some cases, this is because Last Unicorn never got to release the supplements that would have elaborated upon those skills. In others, the skills in question are vague and esoteric in the first place.

Like Attributes, skills are normally rated at 1-5. Over half of the skills are “acquired” rather than “general,” meaning that you can’t try to use them without any training. A few skills and traits are Conditioning-specific--if you don’t get them from your Conditioning (or a related background package) at character creation, you can’t buy them. However, Dune encourages the Narrator to allow characters to substitute one skill for another, with a higher Difficulty depending on how closely the skills are related. For example, if you need to disarm a security shield but you don’t have Security, you could use Repair (shields) or Armament. Although this is good GMing advice, it also points to the overabundance of overlapping skills. The given example is fairly straightforward, but what about the overlap among skills like Economics, Law, and Politics?

One aspect of Dune’s skill system should be singled out for praise: every single skill gives example of routine, difficult, and “nearly impossible” uses of the skill. Many other games have difficulty charts with numbers for “simple,” “difficult,” “legendary,” et cetera, with no examples, no context, and therefore no use. Dune’s examples provide guidance in how to use the skill, which manages to give clues on implementing even the most esoteric skills.

Is it the swords, or the shoes? Gotta be the shoes.

The Valor of the Brave

Armament (Intellect, Swordmasters): This skill is for using and repairing advanced military weapons and defenses, including lasguns, vehicular ordnance, shield generators, and even atomic bombs. Difficult tests include making heavy repairs under fire, or building advanced systems from a junkyard of parts.

Armed Combat (Physique): Melee weapons, plain and simple. The specializations include concealed weapons (such as garottes and flip-darts) and dueling weapons, while exotic weapons like Rabban’s inkvine whip or the Bene Gesserit gom jabbar are specializations of their own.

Athletics (Physique): This gets an entire page devoted to measuring how well characters can move while tumbling, climbing, swimming, or pogo-sticking, not to mention lifting and carrying capacity. Examples of difficult Athletic tests including trying to move at full speed over icy or swampy terrain.

Dodge (Coordination): Self-explanatory. It defends against all kinds of attacks, and the specializations are melee and ranged.

Concealment (Coordination): This is for hiding objects, not yourself. Specializations include Camouflage, “Stashing,” and Sleight-of-hand. Concealing a small weapon on your person is a simple use of the skill; a difficult one is camouflaging a vehicle in a warzone.

Impersonation (Charisma, Assassins): This skill combines disguise, mimicry, and acting to impersonate someone else. A really difficult task would be to convince someone that you’re his best friend.

Infiltration (Intellect, Assassins): Actually sneaking into places is covered by other skills, but Infiltration is used to case the joint and plan the job, so to speak. Assassins use Infiltration to create a plan full of contingencies and useful information. It says that subsequent tests can be used to recall contingencies and data during a mission, but unfortunately, it doesn’t actually give us a metagame mechanism to provide bonuses or prevent failure.

I hope none of the Psi-Stalkers from those Rifts reviews snuck in here.

Military Operations (Intellect, Swordmasters): Like Infiltration, this is a very broad skill which lets us down when it comes to actually applying it. It covers “all tactical and strategic operations” from small unit tactics to a worldwide conflict, and you can specialize in infantry, armored divisions, air battles, or sea battles. However, the only immediate application is making a roll to give all the troops under your command a small bonus for a round. I’m imagining all the Allied troops at the Battle of the Bulge wearing earbuds, listening to George Patton yelling encouragement at them over the radio. Examples of tests include defending a well-armed fortress, or defeating an army that outnumbers you 10 to 1...but are you actually going to make a simple skill Test to determine who wins a major battle? The answer is maybe, because this game doesn’t have rules for battles.

Performance : Performance covers any performing arts, but the Attribute you use depends on the art form. Ha ha, just kidding! You’ll never use this skill, will you?

Ranged Weapons (Coordination): For using and repairing simple ranged weapons such as stunners, maula pistols, and throwing weapons.

Stealth (Coordination): This is the skill that actually covers hiding and sneaking your own self. The difficulty is based on how exposed you are--crossing open terrain in full daylight is very difficult.

Survival (Physique): The skill for finding provisions and shelter in harsh environments. Specialization is by environment. Notably, the deep desert of Arrakis is by default a nearly impossible environment for survival.

Transport (Coordination): This skill covers all kinds of vehicles, land, sea, air, and outer space.