Wizards Presents by gradenko_2000

Races and Classes 1

Original SA post Wizards Presents: Races and ClassesThis book was released by Wizards of the Coast in December 2007 to serve as the first preview of D&D 4th Edition. It was later followed by Wizards Presents: Worlds and Monsters in January 2008.

I wanted to do a read-through of this book because it presents some of the design decisions that went into 4th Edition, specifically as far as how it was still very much based on learnings from 3rd Edition, and not WOTC trying to reinvent the wheel, as it were. I'll be taking excerpts and quotes straight from the book, to let the authors' words speak for themselves.

4th Edition Design Timeline - Rob Heinsoo

quote:

Design Work, Orcus I: June through September 2005

Team: James Wyatt, Andy Collins, and Rob Heinsoo.

Mission: Our instructions were to push the mechanics down interesting avenues, not to stick too close to the safe home base of D&D v.3.5. As an R&D department, we understood 3.5; our mission was to experiment with something new.

Outcome: We delivered a document that included eight classes we thought might appear in the first Player’s Handbook or other early supplements, powers for all the classes, monsters, and rules.

First Development Team: October 2005 through February 2006

Team: Robert Gutschera (lead), Mike Donais, Rich Baker, Mike Mearls, and Rob Heinsoo.

Mission: Determine whether the Orcus I design (as we named it) was headed in the right direction. Make recommendations for the next step.

Outcome: The first development team tore everything down and then rebuilt it. In the end, it recommended that we continue in the new direction Orcus I had established. This recommendation accompanied a rather difficult stunt accomplished in the middle of the development process: Baker, Donais, and Mearls translated current versions of the Orcus I mechanics into a last-minute revision of Tome of Battle: Book of Nine Swords. It was a natural fit, since Rich Baker had already been treating the Book of Nine Swords as a “powers for fighters” project. The effort required to splice the mechanics into 3rd Edition were a bit extreme, but the experiment was worth it.

So that confirms what I had heard previously, that the Tome of Battle was used as a test-bed of ideas that would ultimately be used as a basis for 4th Edition's AEDU model

quote:

One Development Week: Mid-April 2006

Team: Robert Gutschera, Mike Donais, Rich Baker, Mike Mearls, and Rob Heinsoo.

Mission: Recommend a way forward.

Outcome: In what I’d judge as the most productive week of the process to date, not that anyone would have guessed that beforehand, Mearls and Baker figured out what was going wrong with the design. We’d concentrated too much on the new approach without properly accounting for what 3.5 handled well. We’d provided player characters with constantly renewing powers, but hadn’t successfully parsed the necessary distinctions between powers that were always available and powers that had limited uses.

Flywheel Team: May 2006 to September 2006

Team: Rob Heinsoo (lead), Andy Collins, Mike Mearls,

David Noonan, and Jesse Decker.

Mission: Move closer to 3.5 by dealing properly with powers and resources that could be used at-will, once per encounter, or once per day.

Outcome: A playable draft that went over to the teams that would actually write the Player’s Handbook and the Monster Manual.

Right there, the development team acknowledges that they were actually moving too far away from 3.5, had to rein it in, and further flesh out the distinctions between At-Will, Encounter, and Daily powers

The Process of Re-Creation - Rob Heinsoo

quote:

The one-week ORCUS development team realized that Orcus II, as well as earlier drafts, had failed to properly account for attrition powers. Earlier designs had been working too hard on our newfangled renewable powers and hadn’t properly addressed D&D’s legacy of attrition-style powers, powers that went away after you used them once or twice.

So the Flywheel team’s main job was to nudge the eight player character classes away from the flamboyant precipices they’d occupied in Orcus II toward expressions that would look more familiar to players of 3rd Edition D&D.

There's that acknowledgement again of building off of 3rd Edition, and that a core mechanic to D&D's design is attrition .

The chapter goes on to mention that one of the core 8 classes supposed to be the Swashbuckler, but that was abandoned and its cooler powers given to the Rogue and Ranger instead, and then the PHB team created the Warlock instead.

Mike Mearls also gets a special mention as the guy behind the Barbarian and the Druid, which would later appear in the PHB 2.

Design Guideposts - Rob Heinsoo

Guidepost 1: Encourage Player Choice

This talks about how a character should have an interesting choice to make every time they advance in a level, an interesting choice to make concerning their actions with every round of combat, and an interesting choice to make about which and how much of their resources they'd like to spend in-between encounters

Guidepost 2: Provide Information to Help Players and DMs Choose Between Compelling Alternatives

The set of powers that every character class has should help them fill at least one valuable role in an adventuring party, and the players should be aware what those roles are so that the players are making a conscious choice when divvying up the classes between themselves. Likewise, the Monster Manual should contain monsters that similarly serve different roles.

This is also where it's decided that DMs should always let a player know when a monster is Bloodied, so that players don't have to guess how well they're doing, on top of having another property that abilities can key off of.

Notebook Anecdote - Andy Collins

quote:

Things That Would Make Me Happy

All classes effective at all levels. Game is fun and playable at all levels. Dungeon excursions last through many encounters. Game rewards tactical play; smart decisions are “right” (and vice versa). Defeat is meaningful but (usually) not final. Game’s expectations are clearer to players and DMs. Character classes provide compelling archetypes. PC team is a collection of interchangeable parts. All characters can participate meaningfully in all encounters.

In hindsight, we know that "fun and playable at all levels" can tend to break down past Paragon due to the sheer number of powers involved, but "all classes effective at all levels" is a compelling statement to make in the wake of the history between martials and casters.

Orcus Design Tenets - Bill Slaviscek

quote:

5. Three-dimensional Tactics.

We want to continue using miniatures in 5-foot squares. We want to design minis game (skirmish) to work with the RPG. More discussion on how this occurs to follow.

Email: What Is and What Could Be - Andy Collins

quote:

We must force ourselves, instead, to evaluate what the rules set aims to achieve with its various new elements and determine if we believe that a) its goals are appropriate, and b) it’s headed in the right direction to achieve those goals.

For example, whether Class A is better or worse than Class B, or whether the attrition mechanics hit the right balance, is largely immaterial at this stage of design.

What’s much more significant (using the latter example) is whether we think that the idea of reworking D&D’s traditional attrition mechanic to encourage longer-term adventures is a) a good goal that b) we can achieve by developing the concepts presented in the rules set. (That’s one example of a goal/concept from the rules set, mind you, but certainly not the only one.)

I'm almost certain that this mention of longer-term adventures (and again in Collins' Notebook Anecdote) is a reference to Healing Surges as the attritional mechanic and how it allows for parties to engage in many more combats per day than in previous editions.

Heroes in the World - Rob Heinsoo

quote:

3rd Edition had a sweet spot. Somewhere around 4th or 5th level, characters hit their stride, possessing fun abilities and a number of hit points that allow the player characters to stick around long enough to use them. Somewhere around 13th or 15th level, the sweet spot gets a bit sour for many classes. Skilled players frequently disagree with that assessment, but the truth is that many D&D campaigns more-or-less rise out of existence. As PCs pursue the most fun reward in the game—leveling up— they get closer and closer to the levels where the abilities of the strongest characters eclipse those of the weakest characters, where hard math and a multiplicity of choices push DMs into increasingly hard work to keep their games going.

Okay, so on top of acknowledging that the first couple of levels of 3rd Edition were not so good because you were so frail, there's also the note about how the increasing competency and capability of some classes at high-level allowed them to greatly outshine other classes, on top of making it more and more difficult for DMs to create interesting scenarios when these classes have the tools to dismantle a lot of potential obstacles.

The passage ends by explaining that it was a deliberate decision to turn monster creation in 4th Edition away from how 3rd Edition did it - no longer would you construct monsters using class levels and the same use as building PCs, because the PCs are supposed to be "center stage" and the monsters are only as important as their interactions (including combat situations) with the players.

Longswords and Lightsabers - Rodney Thompson

This passage talks about how the Star Wars Roleplaying Game: Saga Edition was, alongside Tome of Battle, another testbed for the ideas that would eventually make it to 4th Edition's core design:

1. Give players options when designing their characters

2. Keep the combat round quick and easy to understand

3. Ability score increases should be handed out more often

4. No more assigning skill points

5. Instead of the defender making saving throws, the attacker would roll to beat a static defense score

6. No more ability damage

7. No more iterative attacks

Chris Perkins is mentioned by name as the main designer behind the Star Wars book and consulted with the 4th Edition developers on porting over these ideas from Star Wars to D&D.

Power Sources - Mike Mearls

quote:

Power sources have always been in D&D, but no one ever bothered to pay attention to them. From the earliest days of the game, it was clear that wizards (then called magic-users) tapped into a different source of magic than clerics. Later on, classes like the druid and illusionist seemed to tie into similar sources, but it was never completely clear. As the game expanded, psionics clearly staked out a completely different source of power.

4th Edition makes the move to create more vivid differences between the sources of magical power. It also creates a source of power for characters who don’t use magic, such as fighters and rogues. While these characters don’t cast spells, at epic levels they eventually gain the ability to perform superhuman feats. After all, some of the greatest heroes of myth and legend toppled buildings with their bare hands, wrestled gods, diverted rivers, and so on. The martial power source allows us to draw a clear line between a mighty hero and the average person in the world of D&D.

[...]

The exciting thing about power sources lies in the design options they open up. Divine and arcane magic are built to serve as independent magic systems, rather than as the core definitions of how magic works in D&D. This decision has a subtle but important impact on design. As noted above, it lets us avoid a kitchen sink approach to spell design. We no longer have to put every single imaginable spell effect into divine and arcane magic, relegating other forms of spellcasting to merely copying existing spells. We are also free to create bigger differences between classes without worrying about straining credibility. A class like the wu jen or the hexblade might use a completely new and different type of magic, allowing us to reinvent the ground rules rather than use what has come before. Since those classes clearly use magic in a different manner when compared to a wizard, we shelve them under a new power source, build a system of magic that works for their needs, and create spells tuned to them rather than simply use the 3E wizard/sorcerer spell list.

There's a lot packed into these three paragraphs.

Power sources were always a thing, they were just never formalized with such a term.

Martial classes needed their own 'power source' to give them the ability to pull off supernatural actions that are still not spells

Spells were the basic building block of every supernatural action (if not just actions, period) in previous editions of D&D, and the fact that there were only either Divine or Arcane spells meant that they all had to be classified into one or the other.

This also meant that without a formal system for creating or defining new power sources, every other class' powers in previous editions had to be based off of an existing spell.

Next up: Races

Races and Classes 2

Original SA post Wizards Presents: Races and ClassesPart 1

Choosing the Iconic Races - Richard Baker

quote:

We decided very early in the process that we wanted character race to play a more important part in describing your character. In earlier editions, your character’s race was something that you chose at a single decision point during character creation. Your race pick bestowed a whole collection of static, unchanging benefits at 1st level (many of which were useless clutter on your character sheet), and never really “grew” with your character. A 20th-level dwarf had the exact same amount of racial characteristics as a 1st-level dwarf—and during the nineteen intervening levels, the overall importance of that long-ago race selection had diminished to a tiny portion of the character concept.

That led directly to the first philosophical shift in the way we look at races: Rather than consider a race a simple package of ability modifiers and special abilities you choose at 1st level, we decided to include higher-level feats that you can choose for your character at the appropriate time. For example, dwarves are extraordinarily resilient, so they gain the ability to use their second wind [a healing ability] one more time per encounter than other characters can. Eladrins gain the ability to step through the Feywild to make a short-range teleport. You might remember that races such as githyanki or drow gained access to unique powers when they reached certain levels; this is an extension of the same principle.

It goes to describe how the idea of feats that only specific races could choose was borrowed from The Forgetten Realms and Eberron Campaign Settings to further allow your racial selection to remain relevant all the way to higher levels.

And then a comparison of designing races from 3rd Edition to 4th Edition:

quote:

A small problem that handcuffed our design in 3rd Edition was the lack of “space” for ability bonuses and special benefits. Because the races in the Player’s Handbook were all balanced against each other, we couldn’t add new races in later products that had significantly better ability modifiers or benefits, because they’d obsolete the core races of the game. The patch we used in 3rd Edition was the notion of level adjustment (more on that later), but with the new game we have a new opportunity to address this problem. Character races now offer a “net positive” on ability score modifiers , so there’s more room for new character races to stand.

By the end of 3rd Edition's run, Baker counts that there was a total of 135 possible player races, so this 4th Edition team had to sit down and cull the list down to what they felt were the most evocative and interesting ones. They toyed with the idea of including a "talking animal" race, especially in the wake of the popularity of the Narnia movies, but had to can the idea because the mechanical design would probably be too difficult and players might regard it as a bad joke.

It was out of that discussion though that lead them down to Dragonborn: 3rd Edition already had multiple varieties of "a dragon man", so they thought of combining them all into a single distinct character race with an interesting backstory and a mechanical niche. As well, the Dragonborn was a sort of commitment (or perhaps one might say token) to introduce a new race into the mix, instead of the first crop of races all being ones that had been created before.

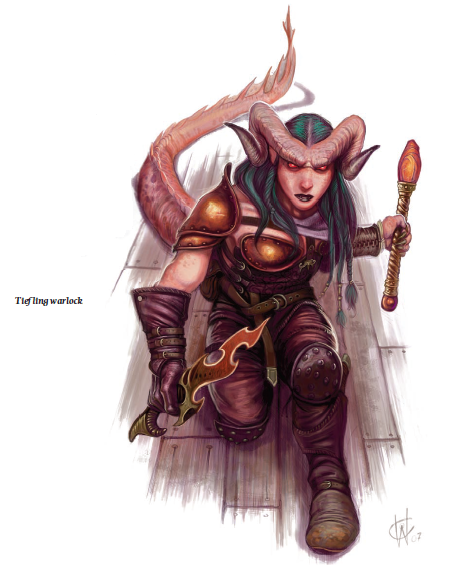

Tieflings were included because they were one of the most popular of the "second-string" races during the 2nd and 3rd Editions, and because they were a good natural fit for the new Warlock race.

It was also during this period that the Halfling was axed:

quote:

For example, halflings were simply too small in 3rd Edition. You could create a halfling who weighed as little as 30 pounds. That’s like a human toddler, not a heroic adventurer. Halflings also lacked a real place of their own in the world; elves had forests, dwarves had mountains, but halflings didn’t really live anywhere.

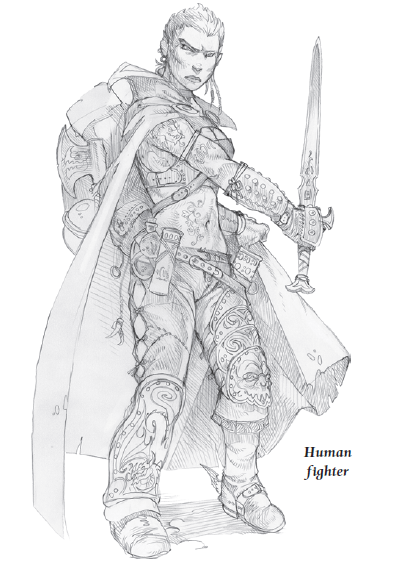

Humans - Matthew Sernett

quote:

The 3rd Edition Player’s Handbook describes humans as “the most adaptable, flexible, and ambitious people among the common races” and human adventurers as “the most daring and ambitious members of an audacious, daring, and ambitious race.” When considering their role in 4th Edition, that seemed great. It’s the same way that humans are portrayed in other works of science fiction and fantasy from Star Trek to Lord of the Rings, and people have a tendency to think of humanity that way in the real world. Yet an aspect of that description bugged us: It’s all positive.

Dwarves are described as suspicious, greedy, and vengeful. Elves are known to be aloof, disdainful, and slow to make friends. Gnomes are reckless pranksters. Half-orcs have short tempers. Each race in the 3rd Edition Player’s Handbook brings with it classic flaws—except humans. Maybe that was because we know human flaws so well, or maybe humans were described in such glowing terms as a means of explaining why we presented them as the dominant race in all of D&D’s published settings. Whatever the reason, it seemed like something that needed to change for 4th Edition.

Humanity needed a weakness—a trait common to all humans that could counteract their adaptability and ambition. It couldn’t be a simple personality trait, such as bad temper, because the infinite variety of personality traits all stem from humanity in the first place. It also couldn’t be something that might come off as odd when highlighted in humanity. If we say that “being fractious” is a big feature of humanity, it makes sense. We fight a lot of wars. Yet highlighting that feature of humanity implies that other races are less fractious, and we want elves fighting elves to be just as likely as humans fighting humans. So what negative trait typifies humanity and works to counteract their potential? What keeps humanity for holding onto the great things it achieves?

In a word: corruptibility.

Sernett then goes on to describe not so much that all humans are corrupt, but that they like to take roads that are paved with good intentions: sometimes it works, and other times it leads down to where that saying says it leads. Humans are ambitious, and that makes them capable of great things, but that ambition can also take the form of a hunger for power. Humans are brave, but bravery can also lead to rash and irresponsible actions. Humans are adaptable, but that adaptability can take on a darker shade when it means people can warp morality into rationalization. Corruption means that the traits humans possess are both their "staunchest ally and most dangerous enemy"

There's also a sidebar from artist William O'Connor about the visual design of humans in 4th Edition: "The candle that burns twice as bright, only burns half as long". Because humans are so short-lived relative to the rest of the other races, human aesthetics are reckless, scavenged and asymmetrical - they don't really care if their boots, gloves or armor aren't matching, because they too busy going all Carpe Diem! on everything for it to matter. Similarly, humans use a lot of representational art such as tattoos, heraldry, crests and standards because they haven't quite reached the sophistication and maturity that has allowed, say, dwarves and elves, to pursue and develop abstract art.

Finally, there's a couple of paragraphs from Logan Bonner on designing the mechanical benefits for humans. It was tricky because all the other races are "humans, but ...", which then leaves you hanging on how the humans actually distinguish themselves. Bonner says they mostly just inherited the 3E design: their attribute bonuses are generic, and they get one free feat - this means they're not really specialized towards one class or role, but at the same time it's never a bad idea for a human to be in any class or role, which suits their theme of adaptability. By the final PHB, the final human bonus was a +1 to defenses, but here Bonner describes it as:

quote:

Humans are our most resilient race. Though they don’t have more hit points or higher defenses, they recover from damage and conditions more quickly than other races can. Humans are all about dramatic action and dramatic recovery. Many of these benefits come from racial feats.

Using the racial feats to emphasize humans’ advantages gives the race an interesting dynamic. Even though they have more potential for some classes, it’s never stupid to play a human of any class. Most classes’ racial abilities intentionally make them lean toward some classes, but humans really can take on any task.

Legend of the Dragonborn - James Wyatt

Note: there's actually a lot of words on every race's chapter about their in-universe origin and other backstory. I'm mostly skipping it as out-of-scope from what I'm trying to relate in this read-through.

quote:

Dragons are such an iconic monster of fantasy that we named the game after them. Until now, though, playing a dragon meant either using a lot of variant rules (as in the 2nd Edition Council of Wyrms campaign setting) or taking on a hefty level adjustment to play either a dragon or a half-dragon.

Not any more.

[...]

If you want to play a proud, battle-bred warrior, if you want to sprout wings and breathe fire as you go up levels, or if you just want to touch the coolness that is dragons, you’ll want to play a dragonborn.

Designing the [Dragonborn's] Visual Look - Stacy Longstreet

quote:

Everyone agreed that this should be a really cool race that everyone would want to play. Yet everyone had different ideas about what it should look like: How much should it resemble a dragon versus how much should it resemble a human? There were lots of discussions and we started with trying to make the head unique by creating a blending of human and dragon. It became very apparent that this had been tried before. We quickly determined that we needed to go in the other direction and work with a more draconic head on a humanoid body.

Designing the male of the race was easier than the female. Like the earlier versions of the dwarves, we did not want the females to look so similar to the males. We wanted them to be more feminine and recognizable as female dragonborn. We gave them the curvy figure of a female and while they are more slender then the males, they are still stronger and bulkier than a human.

Finally, Gwendolyn Kestrel weighs in that it was very much a deliberate decision that they wanted players to be able to play as dragons/a dragon-like race from the very beginning of this edition because of the power and majesty built up with their name over the years of the fantasy genre.

Dwarves - Matt Sernett

quote:

When we designed the 4th Edition of the D&D game, we knew we needed to improve how the game handled special kinds of vision. Out of the three 3rd Edition core rulebooks, only humans, halflings, and lizardfolk need a light to see normally at night. Every other creature possesses some special sight that allows it to see in dim light or even in darkness. That seemed a little crazy , and when we thought about it, the inequality of special vision also complicated the game. To play appropriately, the DM has to describe the big dark room one way for the drow (who has darkvision 120 feet), one way for the dwarf (who has darkvision 60 feet), another way for the elf (who has low-light vision), and still another for the human holding the torch. And there’s one more problem with many creatures having darkvision: The PCs don’t get to see the scenery in caves or large dungeon rooms.

To eliminate those problems we took darkvision away from most creatures, including dwarves. Now dwarves illuminate the homes they build into mountains. They possess low-light vision so they don’t use as much light as a human might, but when the PCs enter the dwarven city, it’s likely everyone can see its splendor.

Besides the gameplay-based change, what stood out to me is that this statement also includes how the lore of the universe reacts to it: Dwarves don't have darkvision anymore, and at the same time the world's internal logic has the dwarves putting up lanterns and sunroofs in their fortresses.

Chris Sims then sets up the racial tension between Dwarves and Orcs: simply having them both live in the mountains would cause conflict out of competition for resources, but then there's also "the two peoples' diametrically opposed world views" : the Dwarves gather and build while the Orcs scavenge and destroy; the Dwarves and dutiful and industrious while orcs are "treacherous and lazy" . The Orcs don't see a point to establishing large and strong permanent shelter nor engaging in agriculture or mining when they can just take stuff from the Dwarves, while the Dwarves have been pillaged by the Orcs so often that they regard them as nothing more than murderers, thieves and despoilers.

And then he has this to say about their mechanical design:

quote:

In the evolution of the D&D game, dwarves have changed little. They’ve always had a clear place and role. In the new edition, the dwarf is a model for how races can be flavorful and still have clear mechanics.

From the early days of the game, dwarves have been tough and soldierly. Only with the advent of racial ability adjustments in the ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS Player’s Handbook did they gain a penalty to Charisma and a cap on Dexterity. Dwarves have been apt at stonework and able to see in the dark since the D&D Basic Rules. In 3E, dwarves still made great fighters, but they became worse clerics than ever due to turning’s reliance on Charisma.

The new edition’s dwarf gives a nod to all its ancestors, while acknowledging the needs of the new edition. Dwarves make great fighters and paladins, and they can excel in leader roles as well, especially as clerics, since they have no Charisma penalty. Flavorful abilities round out the package, reinforcing the dwarf as a defender and as a creature that likes to live underground. Only darkvision, a troublesome game element, went away in favor of low-light vision.

Dwarves still play into the expectations of veteran players, and they live up to the conceptions of myth and fantasy literature. But now, they might fit their intended place in the D&D world better than ever.

Sims then goes on to talk about how they decided to change Dwarves (or some clans of Dwarves) from a fully underground race to a part-surface-dwelling race. It meshes well with how they only have low-light vision: now they need to have their keeps and forts partly aboveground so that sunlight can illuminate the inner halls during the day. As well, it allows the depiction of large dwarven settlements as covering hills or being built into the sides of cliffs or running alongside a mountain instead of just being a large door covering a hole in the ground. Finally, it allows the dwarves to engage in agriculture and raise livestock without having to invent some special grain or special underground-dwelling cow.

In Praise of Dwarf Women - Rob Heinsoo

quote:

Back in the early days, back before D&D first became Advanced . . .

. . . back when D&D players had three pamphlets in a brown or white box . . .

. . . back when Tactical Systems Rules (TSR!) published wargame rules in the same pamphlet format on topics such as modern micro-armor tank battles . . .

. . . back then when D&D was new, there were two topics that resurfaced endlessly in gaming magazines.

First, people argued about the best way to handle lightning bolt and fireball spells. The eventual publication of AD&D provided concrete rules, though that only intensified the Great Fireball Debate.

Second, people argued over whether dwarf women had beards. Yes, it’s true—”Hirsute Dwarven Women” wasn’t a bad-hair band, it was a debate that flared through half a decade of fandom. Remarks by early D&D creators, particularly in reference to GREYHAWK, sparked fanbase suspicions concerning the apparent absence of female dwarves in Tolkien, despite the fact that they were said to be on the scene. Did female dwarves grow beards and move unremarked among dwarf males? Did female dwarves have to shave? Et Tedious Cetera.

So thank Moradin we’re eight years into the Zeds and Bill O’Connor has gifted us with a magnificent new look for dwarf women. Strong, sensual, earthy and feminine, with an exotic beauty that no one would think to splash a beard on. Questions of dwarven female beauty have been buried once

for and all. We’ll have to make do with the Great Fireball Debate.

The Eladrin: Why Fey and Feywild? - James Wyatt

quote:

D&D is emphatically not the game of fairy-tale fantasy. D&D is a game about slaying horrible monsters, not a game about traipsing off through fairy rings and interacting with the little people.

On the positive side, though, there is something very appealing about the legends of a faerie land, a world that’s an imperfect—or a more perfect—mirror of our own. There’s something genuinely frightening about the idea that a traveler in dark woods at night might disappear from the world entirely and end up in a place where the fundamental rules have changed. Magic is more real there, beauty is more beautiful and ugliness more ugly, and even time flows differently in the fey realm. Books like Susannah Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell depict that world in vivid language.

The 3rd Edition Manual of the Planes introduced the idea of Faerie as a plane of existence that lay outside the standard cosmology. It was a parallel plane like the Plane of Shadow, touching the world in many places, similar to it in general form and landscape, but hauntingly beautiful and inhabited by fey. That’s the plane we adopted into the cosmology as the Feywild.

What, then, to do with the cute sprites and good-hearted nymphs? Well, we put the wild back into the Feywild. One aspect of legendary and literary Faerie is that the fey are curiously amoral. They don’t think of Good and Evil in the same way that mortals do, and they can be cruel or murderous almost on a whim. Those are the fey we wanted in the Feywild. The Feywild is home to unearthly eladrins who might call up the Wild Hunt and rampage through the mortal world to avenge some real or imagined wrong, or just because the moon is in a certain phase. Its dryads walk into battle alongside their treant allies, slashing about with branchlike arms. Its nymphs can kill with a glance or enchant mortals to act as their slaves.

Not really much to say here, as this section was mostly about the Eladrin's lore and not much about their mechanical design. The earlier comment about how the Eladrin's teleport remains relevant up to the final level is probably the most relevant.

Next up: Elves, Halflings, Tieflings, other races, and fixing level adjustment

Races and Classes 3

Original SA post Wizards Presents: Races and ClassesPart 1

Part 2

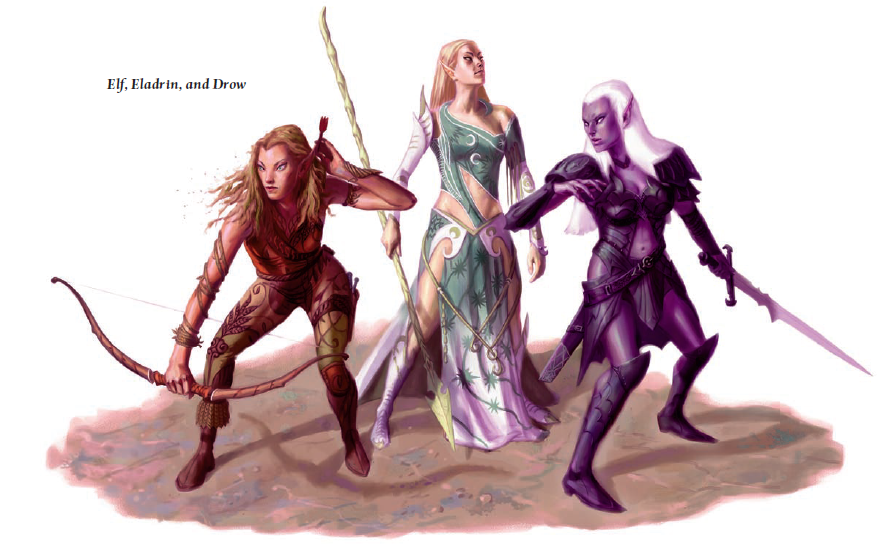

Reconcepting the Elven Look - Richard Baker

quote:

If you take a look at the height and weight suggested for elf characters in previous editions, you’ll discover that elves used to be exceptionally small and slight. It wasn’t unusual for elf characters to stand only about 5 feet tall and weigh less than 90 pounds—about the size of a typical 12-year-old. It’s hard to make a character of that stature look slender and graceful without making him or her extremely small, at least as compared to the humans, dwarves, or half-orcs in the party. So we decided to revisit elf stature for the new edition.

They've modified the Elves to be as tall as humans, if not slightly taller. They're physiques are now "athletic" instead of "emaciated". They're not and won't ever be linebackers, but they do have the long legs and light builds of born runners.

quote:

Elves retain several of their distinguishing characteristics from earlier editions, most notably the pointed ears and the slight tilt to the eyes. And elf males don’t have facial hair. They’re not effeminate; they’re lean, athletic, and clean-shaven. That’s not to say that elves never look feminine—female elves sure do!

All Yesterday's Subraces - Richard Baker

quote:

Somewhere around twenty years ago, the D&D game started to suggest differences between varieties of dwarves and elves. Dwarves were either hill dwarves or mountain dwarves; elves were high elves, wood elves, or gray elves. Of course there were drow too, so that suggested the dwarves might have an evil variety, and thus the duergar were born. Different campaign worlds came up with unique and flavorful names for these varieties, and different abilities too, making even more subraces. So before we knew it, we had a game with a dozen varieties of elves and just as many dwarves—and most had different mechanical characteristics from the basic elf, turning one character race into a dozen.

For 4th Edition, we decided to take a big step back from that. We decided that most of the differences between different types of elves (drow excluded) were cultural, not physical.

The two archetypal Elf characters are the woodland Ranger and the highly-intelligent Wizard, so all of the other Elven subraces were just compressed to those two: Gray Elves, Sun Elves, Moon Elves are all just part-and-parcel of Eladrin, or High Elves, while Wild Elves, Wood Elves and Green Elves are just ... Elves. That trimmed it down to just those two, plus Drow, all three of which are very distinct from each other, especially with the Eladrin having their own unique noun now.

The Evolution of the Halfling — Dave Noonan

quote:

In the beginning (which we’ll call 1974), halflings were hobbits straight out of Tolkien. The D&D game —at that point three booklets and some reference sheets costing $10— even called them hobbits. But then D&D made the transition from an overgrown hobby to a full-fledged product line, and by 1977 all the hobbits became halflings.

Throughout the 1970s and the early 1980s, the D&D halflings still looked and acted like something right out of the Shire—they were often a little plump and they walked around with their fuzzy feet bare. Most of them were thieves, a class that’s conceptually similar to what we’d call a rogue today.

In the mid-1980s, halflings started to move away from the Tolkien vision—spurred on by tens of thousands of D&D players. Bilbo Baggins might have been a reluctant thief, but D&D tables everywhere were full of mischievous, wisecracking, and enthusiastic halfling thieves. The players drove D&D halflings into new territory, and the little fellows became a key repository for much of the game’s humor.

The look of halflings started to change, too. Subraces emerged: the traditional hairfeet, the somewhat dwarflike stouts, and the tallfellows, who were associated with the elves and were only tall when compared to hairfeet and stouts.

Then came the DRAGONLANCE version of the halflings: kender, a diminutive, vaguely elfin race. Talk about a race designed for a mischievous player —kender are impossibly curious, utterly fearless, and they have an instinctive desire to “borrow” things from the pockets and backpacks of whomever is standing nearby. Some players embraced the kender, while others found them a little too far in the “comic relief ” territory. Whether the antics of the kender PC at your D&D table were hilarious or annoying tended to determine how you felt about the kender as a whole.

With the onset of 3rd Edition D&D in 2000, a consensus quickly emerged: retain the halfling’s natural enthusiasm, but shade them a little darker than the kender so they could be more than comic foils. Get them out of their comfortable homes, and for heaven’s sake let them wear boots like everyone else. Halflings became nomadic and had a measure of whimsical trickery—but whimsy that could turn sinister at a moment’s notice. Their visual identity changed, too. Halflings got the lithe physique of gymnasts rather than the portly physique of rustic gentleman farmers.

As we began our work on 4th Edition, we decided that we still liked the 3rd Edition look and feel of halflings—but we needed to continue to evolve the halfling role and appearance in the game.

A long quote, but I thought it was a good historical breakdown. I didn't even know that Kender was supposed to be a direct spin-off of Halflings.

Richard Baker then talks about having to establish where the Halflings would live: Forests went to Elves, Mountains and Hills went to Dwarves, Humans lived in plains (and plains themselves are not very distinctive), so they chose swamps and marshes

There was apparently some apprehension with choosing that as their native terrain because of the generic perception of people that live in swamps as "backwater rubes", but Baker makes the case that it makes sense as far as swamps leading to rivers and coasts, which then follows that sea-travel is the road of choice for non-industrialized societies. As well, swamps are excellent defensive terrain, and fits the 4th Edition depiction of halflings as "waterfolk, skilled boatbuilders and fishers".

Baker ends with a sidebar on halfling size: He acknowledges that their depiction in 3rd Edition as 3 foot, 35 pound humanoids was waaay too small, as that's about the size of a preschooler. The team decided to let adult halflings grow to about 4 feet and 65 pounds. That's still significantly smaller than a human, since the target was "the size of 9- or 10-year old kids", but it's supposed to be much more believable now.

Tieflings - Bruce Cordell

Since they're one of the new races of this Edition, I'm going to include a quote about their origins:

quote:

Sundered from humanity by their ancestors’ overweening ego, tieflings are a race whose bloodline stems from an infernal bargain made nearly a millennia ago.

Lacking any knowledge of their creator and without a purpose instilled by a caring maker, humanity determined its own purposes, but often only by accident. Unpredictable and adaptable, this strangely malleable race claims many an ancient and long vanished empire. One such empire birthed the tiefling race.

Do you recall the whispered stories of Bael Turath? The empire of Bael Turath’s reach exceeded its grasp, but the empire’s ruling nobility were addicted to their own power and glory. They vowed they would retain their rule, no matter the consequences, no matter the cost, no matter what they had to give up. Even their own humanity.

Bael Turath’s brash promises were heard in a distant, burning realm amid the silvery Astral Sea . . . a realm called the Nine Hells.

Whispered secrets slithered into the dreams of those who thirsted most for the continued dominion of Bael Turath, and upon waking, the red-eyed dreamers repeated their visions in the day’s wan light. Those visions were instructions for how the nobility could achieve its ends. A grisly month-long ritual would be required, one that every living ruling house of the empire needed to participate in if the desired effect was to be achieved. The ritual included unsavory and terrible deeds that had to be enacted by each of its participants.

A few houses, even in decadent Bael Turath, refused. These houses were exterminated, and the remaining houses conducted their ritual without naysayers to question their grim certainty.

The ritual began in darkness and blood, and deep into the small hours of the second night, the first devil appeared from Hell’s iron doors. The first was followed by others, each more terrible than the last, and to each pacts were sworn by the power-mad leaders of Bael Turath. Infernal bargains were avowed with names such as the Scarlet Claw of Hunger, the Iron Crown of Madness, Night’s Loving Void, and the Million Pains of Eternal Torment. Though hardly remarked upon at the time of their swearing, the pacts bound not only the nobility present in the hideous ritual, but also promised to mark the descendents of every one present, even unto their last generation, so that no one would ever forget what Bael Turath had agreed to.

And so was born the tiefling race.

Promotion - Chris Perkins

quote:

Tieflings trace their origins back to the 2nd Edition PLANESCAPE® Campaign Setting. With their horns, tails, and wicked tongues, tieflings quickly became the exotic “bad boys” and “bad girls” of the Outer Planes. Sly, sexy, and a little sinister, they afforded D&D players a chance to flirt with the dark side without actually crossing the line into full-blown evil. Why play Drizzt when you could play the great-grandson of a pit fiend?

Tieflings reappeared in the 3rd Edition Monster Manual as one of the “plane-touched,” inexorably bound to their dogooder cousins, the aasimar. Forgive my bias, but I’ll take horns and brimstone over sunshine and perfection any day. Sometimes it just doesn’t pay to be the super good guy.

In 4th Edition, tieflings finally claim their rightful place among the core races. Including them in the 4th Edition Player’s Handbook was an easy, early decision. Their infernal heritage gives them plenty of angst and an excuse to “get medieval” whenever the mood suits them. However, unlike their Machiavellian rivals for coolness, the Underdark-dwelling drow, tieflings are neither confined to the darkness nor afraid to mingle with the surface dwellers. They also carry less evil baggage and enjoy far more autonomy.

In fact, they can pretty much go anywhere they want and do as they please. Players can take the race to either extreme, portraying tieflings that embrace their inner devilspawn as well as tieflings who strive to transcend their twisted heritage and lead honest to semi-honest lives. Or they can play tieflings who walk the line between Good or Evil without fully embracing either.

That kind of versatility makes for a great core race and places tieflings on a footing comparable to humans.

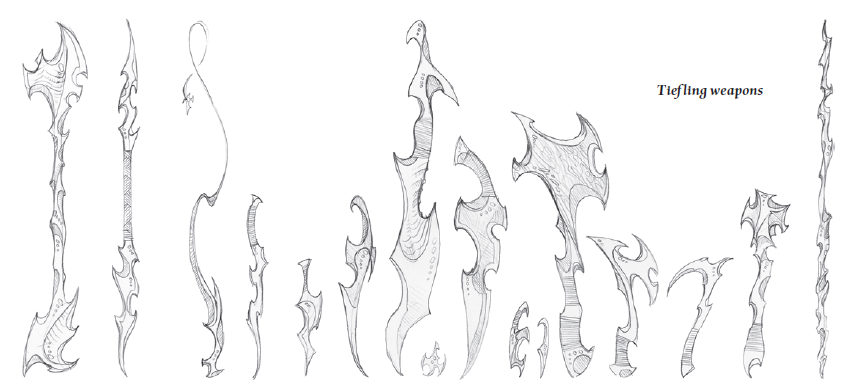

Chris continues to talk about the "cultural appearance" of Tieflings. They adopt Human culture and garb as a means of blending in, but they also try to get away with "infernal-wear" whenever they can. For Tieflings low on the totem pole, it might just be a hellsteel dagger that to a human just looks like a twisted shard of metal, but higher-level Tieflings will often shed all pretense of wanting to fit in and will don outfits specially tailored to show off demonic origins once they're powerful enough to not need to be bashful.

It's Good to be Bad - James Wyatt

quote:

Playing a tiefling (or a warlock, or a drow or half-orc, or any other “bad boy” of D&D) is different from playing an evil character. Part of the appeal of playing a tiefling is that being a hero is both more challenging and more dramatic when you’re overcoming the weight of heritage and stereotype to do it. If Han Solo had burst into the room to save Luke from the Emperor at the end of Return of the Jedi, it would have felt contrived. But the fact that Darth Vader, the great villain of the trilogy, sacrificed himself to save his son—that was powerful. Drizzt Do’Urden is a compelling hero because of the evil society he grew up in, the fear and prejudice he faces on the surface world, and the hatred the other drow of Menzoberranzan still hold for him.

It’s fun to flirt with danger—to walk the edge of the dark side without crossing over. There’s an appeal to playing a character who might not be Evil, but who might be described as “Evil-curious.” It’s a chance to give expression to our dark sides, the parts of our own personalities that we suppress for the sake of getting along in society. Tieflings almost literally embody that dark side, our shadow selves.

Bruce then goes on to describe a design concept for racial ability progression: at first level, a player would choose a single minor ability out of a list, that would grant some small benefit. As the character grew in levels, they would get to choose more traits and even feats, but the initial and succeeding selections would serve as a sort of tree that would chain to some choice while also locking out others. He then ends with a disclosure that this idea had to be refined over three drafts as being overcomplicated.

Other Races: Celestials - Rob Heinsoo

quote:

I won’t lie: making Good-associated creatures as exciting as their Evil-curious counterparts is a challenge. I call the challenge the “Ave Maria” problem, a reference to Walt Disney’s original Fantasia, a wonderful animated film that ended with musical meditations on Evil and Good. Evil got Night on Bald Mountain, accompanied by an evil-storm orchestrated by a whip-wielding demon. Good followed up with barely animated candle-bearing keepers of the faith proceeding across the screen singing Ave Maria. It’s a sweet piece of music, and it certainly speaks to the possibilities of Good, but the animation just didn’t hold a candle to lightning storms on Bald Mountain.

So now you know our mission: celestials who sizzle bright enough to hold their own against Bald Mountain lightning storms. We’re working on it!

He then goes on to explain how he had to campaign to drop the term "aasimar" completely and just go with Celestials instead.

Other Races: Drow - Chris Sims

quote:

Elves. Lolth. Spiders. Underdark. Drow are iconic in the D&D game, and we didn’t fix what wasn’t broken. Drow have changed only to fit into the world of the new edition, evolving in ways that make them more accessible as characters and villains.

Drow are cruel and matriarchal, focused on the dogma of Lolth, their mad spider goddess who was once the deceitful eladrin goddess of shadows and the moon. Lolth took the spider as her symbol, so drow revere all things that share this form.

Another significant change is that drow are fey, but in type only. Drow don’t live in the Feywild, and they don’t work with other fey. They live in the Underdark beneath the world, from where they surface regularly to raid and take prisoners.

The most exciting change is that drow will be available as a player character race without any level adjustment. The average drow isn’t much more dangerous than a human peasant, because drow gain significant abilities as they gain levels.

Other Races: The Trouble with Gnomes - Matt Sernett

quote:

Gnomes lack a strong position in D&D. If you ask someone to name the important races in the world of D&D, gnomes always seem to come in last. They’re elf-dwarf-halflings—a strange mixture of the three with little to call their own besides being pranksters. DRAGONLANCE presented an iconic image of the gnome, but the concept of tinker gnomes and their crazy machines has now been thoroughly used by games such as World of Warcraft, and many D&D players dislike the technological element that version of the gnome brings to the game.

So, what to do with the gnome? How can gnomes be repositioned or reinvented so that the race has a unique position in the world?

World of Warcraft namedrop alert!

Sernett actually ends this section by acknowledging that they haven't actually decided yet. They considered making the Deep Gnome or the Forest Gnome as the standard Gnome, but that seemed to still have the same problem, except more exaggerated. The Whisper Gnomes from Races of Stone were advisors to Elves, so that wasn't a very good idea either since it just continued to make the race play second-fiddle to another.

Finally, they thought about taking the Whisper Gnome idea and putting a darker spin on it: the Gnomes are Feywild fugitives that were former servants to Evil Fey. They weren't too hot on the idea either as being too distant from the Gnomes' roots.

As a sidebar, I'm going to lift a passage from the PHB 2 to see what they had eventually decided upon:

quote:

In the Feywild, the best way for a small creature to survive is to be overlooked. While suffering in servitude to the fomorian tyrants of the Feydark, gnomes learned to hide, to mislead, and to deflect—and by these means, to survive. The same talents sustain them still, allowing them to prosper in a world filled with creatures much larger and far more dangerous than they are.

[...]

Gnomes were once enslaved by the fomorian rulers of the Feydark, the subterranean caverns of the Feywild. They regard their former masters with more fear than hatred, and they feel some degree of sympathy for the fey that still toil under fomorian lashes—particularly the spriggans, which some say are corrupted gnomes. Gnomes are not fond of goblins or kobolds, but in typical gnome fashion, they avoid creatures they dislike rather than crusading against them. They are fond of eladrin and other friendly fey, and gnomes who travel the world have good relations with elves and halflings.

So ... actually fairly close to the last idea Sernett wrote in the preview, but with a somewhat more hopeful tone: they're escaped former slaves , rather than actively working for the Evil Fey.

Other Races: Warforged - James Wyatt

quote:

People are often inclined to play warforged as unfeeling robots, but that’s not how I see them at all. They’re living creatures, and part of living is emotion, attachment, grief, and love. They might have trouble expressing their emotions because of their blank, almost featureless faces, but to my mind, at least, they feel them just as strongly as humans do.

Constructs in 4th Edition don’t have the long list of immunities that they do in 3rd Edition, which made it a lot easier to make warforged playable as 1st-level characters. (Other races also got beefed up a bit, so the 1st-level bar is set a little higher.) You can’t poison a warforged, but you can paralyze him or sap his strength. They’re good at resisting some effects that can hamper other characters, but if you prick them, they bleed—those cords and fibers in their construct bodies carry fluids just as vital to life as blood is to humanoids.

They no longer carry a list of immunities, but warforged are still an attractive option for fighters, paladins, and warlords who can benefit from the stamina and endurance that come with this race

Fixing Level Adjustment - Richard Baker

Baker outright says that they were not happy with the concept of level adjustment. While it made sense from a design standpoint, it was difficult for inexperienced players to understand.

Further, it was "absolute poison" to low-level characters and to any kind of spellcaster. It was maybe okay to compare a level 14 Human Fighter and a level 13 Genasi Fighter, [/i]"but taking a one-level hit on spell progression was just so bad for spellcasters that players quickly learned to not create Genasi wizards and sorcerers."[i]

Dumping level adjustment was a top priority for 4th Edition, and Baker describes a two-pronged approach:

1. Make the basic races more powerful - if even a Human has enough of a racial modifier to be the equivalent of a "+1" or "+2 level adjustment" race, then it's easy to justify giving the more esoteric races the abilities and powers they need to match their in-universe lore.

2. Move the more powerful racial abilities to higher levels

quote:

everyone knows that drow can levitate and cast darkness. But they don’t have to automatically be able to do it at 1st level, do they? Now you decide if you’re playing a drow whether or not those abilities are worth a feat pick (and presumably many or most NPC drow make exactly that choice).

And that ends the section on Races

Next up: Classes

Races and Classes 4

Original SA post Wizards Presents: Races and ClassesPart 1

Part 2

Part 3

Classes Overview - Richard Baker

quote:

Character classes are the heart of the D&D game. Fighters wear armor and mix it up with monsters in melee. Wizards are fragile but use potent spells to swing entire encounters. Clerics heal and rogues sneak. All those things have been true for 30 years, and they’re going to remain true in 4th Edition

I thought the description of Wizards was particularly revealing. It sort of implies that spells should be as potent as Sleep, or that Fireball shouldn't just deal enough damage to hurt a group of monsters, but to guarantee right then and there that you're going to win this particular fight.

Identifying Class Roles - Richard Baker

quote:

One of the first things we decided to tackle in redesigning D&D’s character classes was identifying appropriate class roles. In other words, every class should have all the tools it needs to fill a specific job in the adventuring party. Clerics must heal, fighters must lock up monsters in melee to protect weaker characters, and wizards must deal damage to multiple enemies at range. If you want to exchange characters in the party—for example, replacing a cleric with a druid, or a fighter with a paladin—you should still maintain a mix of high-defense characters, healers, and damage dealers. If you drop in a character who can’t fill the role of the class he’s replacing, you’re weakening the adventuring party and damaging the table’s fun.

We debated long and hard about which roles actually existed, and which classes corresponded to them. Ultimately, we came up with four important roles:

Defender: A character with high defenses and high hit points. This is the character you want getting in front of the monsters and absorbing their attacks. Fighters have been doing this job in D&D for 30 years. Ideally, a defender ought to have some abilities that make him “sticky”—in other words, a defender should be difficult to move past or ignore so that he can do his job.

The defender description I like because it shows that the team understood that "being a tank" was not just about having a bunch of HP and a lot of armor - if the monsters don't want to attack you and they can do that , it doesn't matter.

quote:

Striker: A character who deals very high damage to one target at a time, either in melee or at range. This is the job we want to move the rogue toward—when she positions herself for a sneak attack and uses her best attack powers, she deals some of the highest damage in the game. Strikers need mobility to execute their lethal attacks and get away from enemies trying to lock them down.

Notice that at no point do they mention the Rogue as a "skill-monkey" or as a trap-detector-and-remover, and that they don't call her a Thief anymore

quote:

Controller: A character who specializes in locking down multiple foes at once, usually at range. This involves inflicting damage or hindering conditions on multiple targets. The wizard is a shining example of this role, of course. Controllers sacrifice defense for offense; they want to concentrate on taking down the enemy as quickly as possible while staying at a safe distance from them.

quote:

Leader: A character who heals, aids, or “buffs” other characters. Obviously we thought about just calling this role “healer,” but we want leaders to do more than simply spend their actions healing other characters. The leader is sturdier than the controller, but doesn’t have anywhere near as much offense. The cleric is the classic example. All leaders must have significant healing abilities to live up to their role, as well as other things they can do in a battle.

This paragraph hits on 2 key points that we'd eventually see as part of the 4E design:

1. A Leader's ability to heal was in placed in the action economy so that they could do it while simultaneously smashing faces in, rather than as a mutually exclusive choice

2. The Warlord wasn't just known for being able to heal characters (by shouting), they were known for granting additional attacks for the rest of the party, ditto the Bard for granting additional mobility, and so on.

One Progression Instead of Four - Richard Baker

quote:

In 3rd Edition D&D, each character class began with a skeleton consisting of four distinct progressions: Attack Bonus, Fortitude Save, Reflex Save, and Will Save. In 4th Edition, these have been combined into a single level-based check modifier that applies to all of your character’s attacks, defenses, and skill checks. All 10th-level characters have a +5 bonus to AC, all three defenses, attacks, and so on. Naturally, your ability scores, class abilities, and feat selection impact this single progression, so you can expect that a paladin’s Fortitude defense will be significantly better than his Reflex defense, and likewise better than the rogue’s Fortitude defense. In fact, every class features important attack or defense boosts at 1st level that distinguish their best traits from their ordinary ones.

We think this significantly simplifies character creation and advancement and improves the interaction of characters and monsters. In earlier editions, it was far too easy to accidentally create a monster who could hit the party’s fighter at a reasonable success rate but then would never miss the party’s wizard —or one who hit the wizard at a reasonable rate, but then could never actually land a hit on the fighter. Characters still have significant and important variations in their attacks and defenses, but it’s driven from one simple progression now instead of four.

And here we see the genesis of the Half-Level Modifier. They recognized the problem with good vs poor progression tracks causing problems when comparing one class to the other.

As a related sidebar, there's a section in the 3rd Edition Unearthed Arcana called Maximum Ranks, Limited Choices as an alternative way to track skills. Instead of receiving skill points every level and allocating them across your skills, you simply picked a number of skills you would "specialize" in, and then you would just assume that you always had the maximum possible ranks in that skill.

A Fighter could specialize in [2 + INT modifier] skills.

If they were specialized in Climb, they'd roll [d20 + characterLevel+3 + STR modifier], where characterLevel+3 represents putting all possible skill ranks toward that skill. For any skill they weren't specialized in, they'd roll [d20 + stat modifier].

And therein lies the problem: it was simple to track, yes, but after a few levels you wouldn't have a snowball's chance in hell of hitting the DCs for anything you weren't specialized in, so there'd have to be something added to the non-specialized formula to give you a chance at doing the easy stuff, and maybe even the moderately difficult stuff if you were lucky.

So, let's take this Maximum Ranks, Limited Choices skill system, and make a few changes:

1. Add half your character level to all checks, whether specialized in them or not

2. Consolidate the number of skill categories to about half

Now doesn't that start looking more like the 4th Edition skill system?

Every Class Gets Powers - Richard Baker

quote:

Perhaps the single biggest change in 4th Edition D&D is this: Every character class has “spells.” In other words, every class has a broad array of maneuvers, stunts, commands, strikes, heroic exploits, or what-have-you to choose from, just like clerics and wizards in previous editions had a wide assortment of spells. Ultimately, a spell, curse, weapon trick, or command is at heart a “power”—a special ability that a character can trigger in a fight.

There are a couple of reasons we decided to do this.

First, all previous editions of the game simply placed far too much of the adventuring party’s total power in the spell selections of the cleric and the wizard. These classes were simply better than other classes by any objective standard. Characters such as fighters and rogues accompanied the adventuring party to protect the spellcasters while the spellcasters defeated the encounters. We decided to shift to a model in which all characters were equally vital to the party’s success. That required offering powers for the fighter and rogue to choose from, just like the cleric and wizard.

Second, choosing and using powers is fun. Fighters in 3rd Edition D&D had many more options than fighters in previous editions thanks to feats such as Power Attack , Spring Attack, and Combat Expertise, but for the most part, fighters still spent 90% of their rounds doing the exact same thing time after time— taking a basic melee attack. A selection of powers to choose from means that fighters now have real choices available to them in combat. From round to round, they decide whether to employ one of their once per encounter abilities, expend a precious once-per-day power, or conserve resources and execute one of the simple at-will attacks they know. Every round is different for the fighter in 4th Edition D&D, and that’s lots more fun.

We’ve also given characters something to add to their power mix at every level, so that a character always gets meaningfully better every time he or she advances a level. There’s always a choice, and always something cool to look forward to every time you level up your character—and that just adds to the fun of the D&D game.

I'm just going to let that stand on its own with emphasis because by God if that doesn't sum up the core of 4th Edition for me. You just wanna frame it.

Next up: The Cleric

Races and Classes 5

Original SA post Wizards Presents: Races and ClassesPart 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Clerics

He doesn’t necessarily hit you with his sword arm. He hits you with his faith.

—Andy Collins, March 2006

Class Role - Logan Bonner

The cleric is the archetypal leader. They use their divine magic to buff their allies and prevent them from dying. The different deities that a cleric would worship will grant them unique benefits, such as a preferred weapon or a defense bonus.

They are melee combatants, and their physical attacks are empowered by their divine magic. An individual cleric might choose to specialize in singling out enemies for death, or lowering an enemy's defenses, or increasing an ally's prowess.

Their main combat powers are in the form of battle prayers and spells. Effects that they're capable of include fire and light coming down from above, inducing an enemy to free, or preventing an ally from getting hurt.

quote:

All 4th Edition characters have some ability to heal themselves and all leaders can increase that healing. A cleric grants all allies near him an increase to their self-healing, and he can also cure their wounds by using healing words. A cleric doesn’t spend any of his other spells to use them, nor will he need to spend the lion’s share of his actions healing others.

Rituals allow a cleric to heal persistent conditions, create wards, and even bring people back from the dead. Many 3E spells have become rituals instead, allowing the cleric to fill his spell and battle prayer lists with proactive attacks and enhancements.

Just pretend I bolded the whole passage, because these are all key points in 4E's design:

1. Everyone can heal themselves

2. Leaders are "healers", but not just healers

3. Even when leaders are healing, healing isn't supposed to come at the expense of more "interesting" actions

4. Critical/powerful/epic/game-changing spells have been urned into rituals, so casters are still capable of them, but they're not taking up a caster's "spell slots"

Sidebar: Why we changed the Gods - Matt Sernett

quote:

We didn’t move forward in 4th Edition with that pantheon [from 3rd Edition, which was heavily based on the Greyhawk campaign setting] because its deities weren’t designed for the improved experience of D&D we were forming. Also, its ties to Greyhawk and its uses in 3E wouldn’t sync up with the new cosmology and mythology we’ve designed to be better for play. We struggled with what deities to put in the game for a long time, and many factors influenced our final decisions:

• We don’t want deities to be thought of as omniscient and all-powerful. Omniscience and omnipotence makes it difficult to use gods in adventure plots or have them interact with characters.

• We want epic characters to be capable of challenging gods and even of becoming gods.

• We wanted deities to be designed for play in the D&D world. Sure, it’s realistic in a sociological sense to have a deity of doorways or of agriculture, but it’s hard to figure out how a cleric who worships such a deity honors his god by going on adventures.

• We wanted fewer, better deities. In your campaign, you can have as many deities as you want, but in order to design classes, a cosmology, and products that work well together, we wanted a good set of deities that cover most players’ needs without that pantheon being too complex and cumbersome.

• We wanted deities to represent the new game and new vision for the D&D world.

For a long time we wanted to design a pantheon that was wholly new, but the harder we pushed it in that direction, the more it seemed like some of the deities of the 3E pantheon were a good fit for the game’s needs. Thus, the pantheon is a blending of old and new.

3E Clerics Rule! 4E Clerics are Better - Logan Bonner

quote:

It’s no secret that 3rd Edition clerics are really good. 4th Edition clerics are no longer better than other classes, but are more fun to play.

The huge difference between the two versions is that clerics no longer spend all their time healing and buffing. Moving a modest amount of self-healing into every class has really loosened up the reins on the cleric, as has putting healing in its own bin so it doesn’t overshadow offensive magic. We expect that, in an average encounter, a cleric will use one standard action to heal and will be using the rest of his actions for offense.

Bonner then goes on to explain how they had to chop down the 3E Cleric spell list. Everything that belonged in rituals, such as restoration, raise dead, cure x, and wards were all moved there, and lots of healing prayers were also removed or made into rituals.

This is also the first mention of "alignment no longer has a major mechanical effect" , and that's another big pile of spells that can be done away with. Summoning spells were also removed, but were expected to come back in later books.

In exchange, the designers were able to play around with all sorts of new effects instead:

quote:

we wrote a ton of new cleric powers! We wanted persistent magical effects that the cleric could maintain over many rounds (such as spiritual weapon), big magical attacks (like flame strike), and short-term buffs. Most persistent effects sit in the battle prayers, so a cleric drops one in every fight, usually to keep an enemy under control. Big attacks can be found in battle prayers and in spells. They include big explody things like flame strike, supernatural weather (inspired by storm of vengeance), and spells that utterly crush a single opponent. Short-term buffs are much improved because we did away with the duration-tracking that was such a big part of cleric life in 3E. Most short-term buffs lasts until the end of the encounter. That’s it. It’s simple, it’s clear, and the effects are more powerful since the duration’s shorter.

So you might miss the 3E cleric if you just have to be a bit overpowered or were such an altruistic soul that you liked healing somebody every round, but we think most players will prefer the new cleric over the old.

Fighters

If you don’t choose a defender, the monsters will choose one for you.

—Richard Baker, November 2005

Class Role - Richard Baker

Fighters are the classic defenders. They get in front of the monsters and keep the monsters from attacking less resilient members of the party.

They have the most HP and can wear the heaviest armor. There are even certain feats that will allow a Fighter's DEX to be added to their AC even while wearing heavy armor, that only Fighters will have access to. Fighters also have the most self-healing, and only a Paladin is supposed to even come close to being as tanky.

quote:

The second quality a defender requires is an ability to keep the monsters focused on him. We called this “stickiness” around the office—once you get next to a fighter, it’s really hard to move away in order to go pound on the party wizard or cleric. Fighters are “sticky” because they gain serious bonuses on opportunity attacks, have the ability to follow enemies who shift away from them, and guard allies nearby through an ability called battlefield control. Once the fighter gets toe-to-toe with the monsters, it becomes very dangerous for the monsters to do anything other than battle the fighter . . . which is, of course, what the fighter excels at. Enemies ignore fighters at their peril!

Fighters have Power! - Richard Baker

quote:

In previous editions of the DUNGEONS & DRAGONS game, the fighter has always been the character who didn’t have any spells or special class powers. Generally speaking, a player running a fighter character did the same thing every round: He took a swing at the bad guys. In 3rd Edition D&D more options became available through the use of various feat trees, but it was still true that the fighter offered none of the resource management or battle strategy of a spellcasting character. Tome of Battle: The Book of Nine Swords introduced a new twist on the 30-year-old mechanics of the fighter class by describing fighterlike classes who used a variety of spectacular martial maneuvers. Using Tome of Battle you could play a fighter (well, a warblade) with the tactical challenge of choosing when and how to use dramatic maneuvers. The new DUNGEONS & DRAGONS 4th Edition game improves and expands this concept even more.

Baker then mentions the AED system for the first time:

At-wills are attacks that are simple, but the Fighters knows and can do all the time. The example given is a Defensive Strike that gives the Fighter an AC bonus whenever the Fighter hits.

This next passage settles a debate that AFAIK kept cropping up on the internet back in the day:

quote:

Per-encounter powers are special weapon tricks, surprise attacks, or advanced tactics that can only be used one time per fight. The fighter doesn’t “forget” a power once he uses it, nor does a power deplete any innate reserve of magical energy. He can’t use it again because it simply isn’t effective more than once per battle. If an enemy has already seen your dance of steel maneuver, he won’t be taken in by it a second time. Because you can use one of these powers once per battle, the challenge is to find the exact right moment to use each one for maximum effect

And finally per-day powers "represent a single act of incredible strength, endurance, and heroism; the fighter digs down deep and finds what he needs to make the ultimate effort." The example given is Great Surge that will let a Fighter deal a devastating attack while also tapping into their healing reserves simultaneously. If the interesting part of using an Encounter power is which round of the fight to use it in, the interesting part of a Daily power is deciding which of the battles within the day do you really need it.

Supporting Different Builds - Stephen Schubert

quote:

The fighter has always been one of the four iconic pillars of the D&D game (along with the cleric, wizard, and thief/rogue). As the game progressed, the fighter grew into an extremely customizable class, especially in 3rd Edition D&D, where a fighter’s feat choices could change the way he looked: was he a lightly armored, Spring Attacking, glaive wielder? A Power-Attacking, greatsword-swinging, damage dealer? An impregnable, Combat Expertise-using, sword and board AC junkie? Or maybe just a spiked chain trip monkey?

The new fighter still allows for such customizations within the role defined for the class. The class “builds” are supported through feats, class features, gear, and power selection, with each aspect of character creation adding its own flavor to the mix.

Schubert acknowledges that the main divide for Fighter builds tends to be between the sword-and-shield Fighter and the two-handed weapon Fighter.

For the former, there are feats and powers that improve a Fighter's AC and ability to defend their allies, but the designers didn't just want to give the Fighter nothing but defensive bonuses, so there are always powers that would allow the Fighter to quickly move around to battlefield, to get in the way of monsters before they reach the rest of the party, or to pursue and stop monsters that are trying to slip away.

For the latter, the Fighter will have access to "Power Attack-like abiltiies that give the options of dealing more damage with a less accurate swing" , but also attacks that trigger when the Fighter's allies are attacked, effectively allowing this kind of Fighter to still defend their team by threatening the enemies with massive damage if the enemies try to attack someone else.

The powers system is supposed to be flexible enough to support multiple playstyles: if the game needed a build for a "dancing fencer" or a "two-weapon Fighter" , it would just be a matter of adding appropriate powers and feats for it. Finally, the term "build" isn't supposed to be a strict choice. If a sword-and-shield Fighter wants to pick up powers to let them deal more damage, they can choose even those that were originally designed for the two-handed weapon Fighter.

Sidebar: Influence of Book of Nine Swords - Richard Baker

quote:

If you think you’ve seen the idea of per-encounter powers for fighters before, you’re right. Tome of Battle: Book of Nine Swords built a system of maneuvers for martial characters that presaged many of the nonspellcaster powers coming up in 4th Edition D&D.

At one point in our power design, we examined the idea of whether or not character powers could be constructed more or less like a card-game model. In other words, all the power choices available to you would be your “hand,” and when you used a power in a fight, you’d “discard” it. In fact, you might even have important “draw” or “refresh” mechanics to return discarded powers to your hand. One of the most aggressive ideas of this sort was the notion of a character who drew his hand randomly as the fight progressed. So, to test the acceptability of these changes to our audience, we adopted the classes in Book of Nine Swords to use an execute, discard, and refresh system for their maneuvers.

While the Nine Swords classes actually work fine with the system (even the crusader!), we eventually moved away from the idea of maneuvers refreshing in an encounter. We decided that we didn’t want to make the players play a game of managing their “hands” at the same time they were playing a game of defeating the monsters. But we learned a tremendous amount from watching D&D fans play with the rules in Book of Nine Swords. And heck, they were fun enough that most of our D&D games around the office saw plenty of Nine Swords characters enter the dungeon.

Next up: The Rogue

Races and Classes 6

Original SA post Wizards Presents: Races and ClassesPart 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Rogues

Class Role - Logan Bonner

quote:

The rogue is the prime example of a striker. Capable of delivering more damage to a single target than many other characters, a rogue has to spend some effort setting up such a boost. By skillful maneuvering, the help of allies, and the occasional dirty trick, a rogue sets up devastating attacks. In exchange for high damage, a striker ends up frail compared to a defender.

The rest of the section talks about how hiding in shadows, jumping over enemies and scaling walls are all tricks that the Rogue uses to set-up their attacks, and they can do these things because they can use their skills more effectively than other classes, and that the skill system for 4th Edition itself has been revamped.

Sneak Attack is also touted as a source of a Rogue's damage, and it's been made easier to use and more widely applicable. Both the skill revamp and the Sneak Attack changes will be talked about further in.

The last source of a Rogue's bighuge damage is supposed to be their "follow-up attacks", which are tacked onto the end of successful normal attacks to make for flashy results and also good numbers output.

Sneak Attack - Mike Mearls

quote:

In the beginning thieves had the backstab ability, and it was good. A +4 bonus on attacks and double damage were great back in the day, but they came with a catch. It was really, really hard to actually complete a backstab. The rules were vague about how they worked, and most DMs shied away from allowing thieves to use this ability on a routine basis.

When D&D 3E arrived on the scene, gamers who loved rogues had reason to celebrate. Sneak attack, while perhaps not as swingy as backstab, was clearly implemented and easy to use. Those extra d6s of damage were great. At least, they were great when the rogue got to use them. Entire categories of creatures, most notably undead and constructs, were immune to sneak attack. Without the offensive boost provided by this ability, rogues were severely crippled.