Cypher System Corebook by gradenko_2000

The core mechanic

Original SA postI've read through the

Cypher System Corebook

, or the book setting-agnostic, system-only version of

Monte Cook's Numenera

, and in lieu of a full page-by-page review I'm just going to talk about it here because you really don't want or need me to go through this whole 400 page thing just to make a point.

The core mechanic:

1. The GM sets a number from 1 to 10 to represent the difficulty of a task

2. A player's Skills can reduce the difficulty number by 1 or 2

3. A player's Assets, which is a more generic term for a circumstantial bonus, can further reduce the difficulty number by 1 or 2

4. A player can spend Effort, which costs points out of their stat pool, in order to further reduce the difficulty number yet again

5. A player's Edge can reduce the cost of the Effort so that you don't need to spend as many points from your stat pool just to get the same difficulty reduction

6. If at any point between 2 to 5 the difficulty is reduced to 0, then the player succeeds automatically

7. If the difficulty is still at least a 1, multiply it by three to get a target number, and then the player rolls a d20, and they succeed if they get higher than the target number

It should be fairly obvious what the problem with all this is:

despite being marketed as such, it's not actually a rules-light game.

I got about 50 pages into character creation before I realized that keeping track of your skills, your stat pool, your Edge, your activated special abilities and your situational modifiers is going to be an awful lot of book-keeping even when you're comparing it to something like D&D 3.5, because at least there "make a Climb check" means looking up a single pre-calculated number and adding it to your d20.

A real rules-light game like say Lasers and Feelings gets by with something like "throw one die baseline, add another if your class/skill applies, add another if you have a situational bonus" and then you look for a number of successes. John Harper's Blades in the Dark ups the ante a bit by also including "throw one die at the cost of some effort" and you're starting to get something that more closely resembles Cypher's core mechanic, but they're doing it by adding whole dice as a broad, quick-to-remember guideline rather than having you muck around with integer math.

And I get that no writer is ever going to really disparage their own work inside their own book, but it really sounded

obnoxious

to me how in both the GM section and in the introductory section Cook just goes on and on about how this system is such a better way of doing things, primarily because

the target number is supposed to be based on the task itself, irrespective of the "power level" of the characters.

That is, if they're trying to cross a particularly deadly bridge, you assign a certain difficulty to it, and that's supposed to be the target number of that task forever. Whereas in any other game you might "adjust the difficulty" if the players try it again 2 levels later, the players instead are going to have a better set of Skills, Assets, Pools and Edges to deal with it, so that maybe where they could only lower the bridge's difficulty from 4 to 2 before, they can reduce it from 4 to 1 now. Or they reduce it to 0 and succeed automatically!

I don't really agree with this approach though because by implication

it means Monte Cook is still designing a simulationist game at heart.

Of course you're supposed to adjust the difficulty of certain tasks -

because you only want to focus on the things that are exciting or produce tension!

If the party is making their way through an abandoned installation with a bunch of closed doors, you don't need to make them roll against opening every single door up until you get to the one that they need to open to escape the Big Bad in a hurry.

quote:

When do you roll?

Any time your character attempts a task, the GM assigns a difficulty to that task, and you roll a d20 against the associated target number.

When you jump from a burning vehicle, swing an axe at a mutant beast, swim across a raging river, identify a strange device, convince a merchant to give you a lower price, craft an object, use a power to control a foe’s mind, or use a blaster rifle to carve a hole in a wall, you make a d20 roll. However, if you attempt something that has a difficulty of 0, no roll is needed—you automatically succeed. Many actions have a difficulty of 0. Examples include walking across the room and opening a door, using a special ability to negate gravity so you can fly, using an ability to protect your friend from radiation, or activating a device (that you already understand) to erect a force field. These are all routine actions and don’t require rolls.

Using skill, assets, and Effort, you can decrease the difficulty of potentially any task to 0 and thus negate the need for a roll. Walking across a narrow wooden beam is tricky for most people, but for an experienced gymnast, it’s routine. You can even decrease the difficulty of an attack on a foe to 0 and succeed without rolling.

So instead of a system where the GM is just free to handwave a task as not needing a roll right now because it's not dramatically relevant, what Cook seems to be proposing is that any moderately complex/difficult task still has to be rolled for ... except when you assume that a combination of Asset+Skill+Effort+Edge will passively reduce the difficulty to 0 so that you succeed anyway, which is functionally equivalent to letting the GM just handwave-away certain tasks in the first place!

I'm just going to leave it at that for now because I realize there's more to this book than I want to cover in a single post.

More nonsense

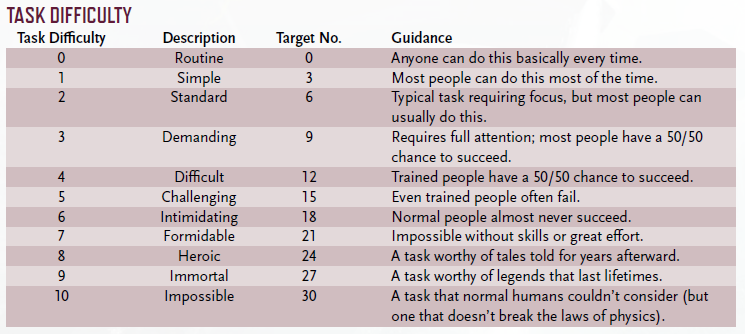

Original SA post Cypher System Corebook, part 2I’m going to talk more about core mechanics, starting with this table:

I remember Tulul’s original F&F of Numenera being quite puzzled at the description of Task Difficulty 3 versus Task Difficulty 4, but I think I’ve got it:

Task Difficulty 3 translates to a target number of 9, so you have a 50/50 chance of succeeding on a raw roll of a d20. Task Difficulty 4 has a target number of 12, but it says trained people have a 50/50 chance of succeeding. What it’s trying to convey is that according to the rules of the game, if you’re Skilled in a task, then a Task Difficulty 4 is dropped to a Task Difficulty 3. It’s not really contradictory, wrong or redundant, just very confusingly worded.

quote:

For example, we make the distinction between something that most people can do and something that trained people can do. In this case, “normal” means someone with absolutely no training, talent, or experience. Imagine your ne’er-do-well, slightly overweight uncle trying a task he’s never tried before. “Trained” means the person has some level of instruction or experience but is not necessarily a professional.

Anyway. Let’s recap: the GM designates a Task Difficulty, then a player has three options to reduce the Task Difficulty: Skills, Assets and Effort.

At the same time, a character is composed of 3 parts: their

A character’s Descriptor defines their Skills.

A character with the Clever descriptor:

quote:

Skill: You’re trained in all interactions involving lies or trickery.

Skill: You’re trained in defense rolls to resist mental effects.

Skill: You’re trained in all tasks involving identifying or assessing danger, lies, quality, importance, function, or power.

A character with the Graceful descriptor:

quote:

Skill: You’re trained in all tasks involving balance and careful movement.

Skill: You’re trained in all tasks involving physical performing arts.

Skill: You’re trained in all Speed defense tasks.

This is where the game kinda-sorta plays around with the idea that it’s a “rules-light” or “story” game, because the definitions of what you’re skilled in can be quite broad, and you could maybe even make the case that if you approach a task gracefully, then you can still consider yourself Skilled in that task.

A character's Role defines the following:

1. The starting size of their Might, Speed and Intellect pools

2. The starting Edge value for their Might, Speed and Intellect pools

3. The cap on how much Effort they can exert

4. Their special abilities

A Warrior, for example, has a Might pool of 10, a Speed pool of 10, and an Intellect pool of 8. They also have a Might Edge of 1 and an Effort cap of 1.

The way this works is that you spend points from your pool to exert Effort, and exerting Effort reduces the task difficulty. You can spend 3 points from a pool to reduce the task difficulty by 1, and more effort after that costs 2 points to further reduce the task difficulty, so reducing the task difficulty by 2 requires 5 points: 3 points for the first Effort, 2 points for the second Effort.

The Effort cap means you cannot exert more than that much Effort at any one time, so while a character might have a pool of 10, they can't exert more than 1 Effort (3 points) for any given task.

Edge reduces the point cost of any expenditure you make. If a Warrior wanted to reduce the task difficulty of a Might task by exerting 1 Effort, it would cost them 2 points: 3 points base - 1 Might Edge. If they exerted Effort with a Speed or Intellect task, the Effort would cost them 3 points, because they don't have Edge in those stats (yet).

Edge also applies to any special abilities that cost points from your pool.

quote:

Control the Field (1 Might point): This melee attack inflicts 1 less point of damage than normal, but regardless of whether you hit the target, you maneuver it into a position you desire within immediate range. Action.

The above would cost the Warrior nothing to activate/use, because it costs 1 Might but the Warrior has 1 Might Edge.

quote:

Overwatch (1 Intellect point): You use a ranged weapon to target a limited area (such as a doorway, a hallway, or the eastern side of the clearing) and make an attack against the next viable target to enter that area. This works like a wait action, but you also negate any benefit the target would have from cover, position, surprise, range, illumination, or visibility. Further, you inflict 1 additional point of damage with the attack. You can remain on overwatch as long as you wish, within reason. Action.

The above would cost the Warrior 1 Intellect.

Finally, a character's Focus gives them yet another set of special abilities:

quote:

Bears a Halo of Fire

Additional Equipment: You have an artifact—a device that sprays inanimate objects to make them fire-resistant. All your starting gear has already been treated unless you don’t want it to be.

Fire Abilities: If you perform special abilities, those that would normally use force or other energy (such as electricity) instead use fire. For example, force blasts are blasts of flame. These alterations change nothing except the type of damage and the fact that it might start fires. As another example, a wall of energy instead creates a wall of roaring flames. In this case, the alteration changes the ability so that the barrier is not solid but instead inflicts 1 point of damage to anything that touches it and 4 points of damage to anyone who passes through it.

Tier 1: Shroud of Flame (1 Intellect point). At your command, your entire body becomes shrouded in flames that last up to ten minutes. The fire doesn’t burn you, but it automatically inflicts 2 points of damage to anyone who tries to touch you or strike you with a melee attack. Flames from another source can still hurt you. While the shroud is active, you gain +2 to Armor only against damage from fire from another source. Enabler.

quote:

Carries a Quiver

Additional Equipment: You start with a well-made bow and two dozen arrows.

Tier 1: Archer. To be truly deadly with a bow, you must know where to aim. You can spend points from either your Speed Pool or your Intellect Pool to apply levels of Effort to increase your bow damage. As usual, each level of Effort adds 3 points of damage to a successful attack. Enabler.

Fletcher. You are trained in making arrows. Enabler.

It's no accident that I'm trying to juxtapose "guy who is literally on fire" with "guy who can shoot arrows"

The last thing I haven't mentioned is Assets , these are basically both "roleplayed circumstantial bonuses" and "a way to explicitly grant a bonus from a special ability"

The following excerpt from the book covers the former use of Assets (as well as Effort and Edge):

quote:

A beginning character is fighting a giant rat. She stabs her spear at the rat, which is a level 2 creature and thus has a target number of 6. The character stands atop a boulder and strikes downward at the beast, and the GM rules that this helpful tactic is an asset that decreases the difficulty by one step (to difficulty 1). That lowers the target number to 3. Attacking with a spear is a Might action; the character has a Might Pool of 11 and a Might Edge of 0. Before making the roll, she decides to apply a level of Effort to decrease the difficulty of the attack. That costs 3 points from her Might Pool, reducing the Pool to 8. But they appear to be points well spent. Applying the Effort lowers the difficulty from 1 to 0, so no roll is needed—the attack automatically succeeds.

Where a GM might award a +2 to a +4 on a d20 roll in other D&D games after the player declares that they're swinging from a chandelier while making an attack, here it's called an Asset and is the functional equivalent of a +3.

And then an example of Assets in the latter case:

quote:

Distortion (2 Intellect points): You modify how a willing creature within short range reflects light for one minute. The target rapidly shifts between its normal appearance and a blot of darkness. The target has an asset on Speed defense rolls until the effect wears off. Action to initiate.

So it's a video game equivalent of a buff, and where in D&D this might be a Barkskin spell or whatever to provide a bonus to AC, here it's an Asset.

All this to say that there is an awful lot of fiddly math in this game.

1. The GM sets a task difficulty.

2. If the character, which the game proposes as being described as "an Adjective Noun that Verbs" (or further translated to "a Descriptor Role that Focus"), is Skilled at the task, and Skilled is a broad, 13th-Age-esque definition, then the task difficulty drops by 1 or 2. Okay, makes sense.

3. If the character has any other temporary or circumstantial bonus, then the GM can rule it as an Asset and the task difficulty drops by another 1 or 2. Still good. Step #2 is Lasers and Feelings' extra die if you're an expert, and step #3 is the extra die if you're prepared.

4. And then you get to the part where if you still want to reduce the task difficulty further, you need to spend 3 points from your pool to reduce the task difficulty by 1, except if it's the second Effort you're spending in which case it's only 2 points per Effort, but only if your Effort cap will allow you to exert more than 1 Effort, and then you subtract your Edge from the total point cost. Ouch.

5. And then you multiply the task difficulty by 3 to get the target number you need to beat with a d20 roll.

I don't even really get the point of the d20 conversion:

quote:

Rarely, an ability or piece of equipment does not decrease a task’s difficulty but instead adds a bonus to the die roll. Bonuses always add together, so if you get a +1 bonus from two different sources, you have a +2 bonus. If you get enough bonuses to add up to a +3 bonus for a task, treat it as an asset: instead of adding the bonus to your roll, decrease the difficulty by one step. Therefore, you never add more than +1 or +2 to a die roll.

This is a cop-out because none of the equipment nor Cyphers nor special abilities (that I've been able to scan through) award that partial +1 or +2 bonus, so it's only ever going to come into play if the GM wants to for whatever reason.

Finally, in response to this:

Halloween Jack posted:

It actually sounds like he made a deliberate sop to people who believed that "When high-level characters cross bridges, it's magically harder to cross them!" canard about D&D 4th edition.

I think he actually did do that, because he talks about it quite a bit:

quote:

If you’re talking about a task, ideally the difficulty shouldn’t be based on the character performing the task. Things don’t get inherently easier or harder depending on who is doing them. However, the truth is, the character does play into it as a judgment call. If the task is breaking down a wooden door, an 8-foot-tall (2 m) automaton made of metal with nuclear-driven motors should be better at breaking it down than an average human would be, but the task rating should be the same for both. Let’s say that the automaton’s nature effectively gives it two levels of training for such tasks. Thus, if the door has a difficulty rating of 4, but the automaton is specialized and reduces the difficulty to 2, it has a target number of 6. The human has no such specialization, so the difficulty remains 4, and he has to reach a target number of 12. However, when you set the difficulty of breaking down the door, don’t try to take all those differences into account. The GM should consider only the human because the Task Difficulty table is based on the ideal of a “normal” person, a “trained” person, and so on. It’s humanocentric.

I can feel my brain straining under the weight of this paragraph because he's just using circular logic to bring himself back to the way GM's have (ideally) always assigned target numbers in the first place.

quote:

Far more important than that level of precision is consistency. If the PCs need to activate a device that opens a spatial displacement portal, and the GM rules that it is a difficulty 6 task to get the antimatter rods spinning at the proper rates to achieve a specific harmonic frequency, then it needs to be a difficulty 6 task when they come back the next day to do it again (or there needs to be an understandable reason why it’s not). The same is true for simpler tasks like walking across a narrow ledge or jumping up onto a platform. Consistency is key. The reason is that players need to be able to make informed decisions. If they remember how hard it was to open that portal yesterday, but it’s inexplicably harder to open it today, they’ll get frustrated because they tried to apply their experience to their decision-making process, and it failed them. If there’s no way to make an informed decision, then all decisions are arbitrary.

Think about it in terms of real life. You need to cross the street, but a car is approaching. You’ve crossed the street thousands of times before, so you can look at the car and pretty easily judge whether you can cross safely or whether you have to wait for it to pass first. If the real world had no consistency, you couldn’t make that decision. Every time you stepped into the street, you might get hit by a car. You’d never cross the street.

Players need that kind of consistency, too. So when you assign a difficulty to a task, note that number and try to keep it consistent the next time the PCs try the same task. “Same” is the key word. Deciphering one code isn’t necessarily like deciphering another. Climbing one wall isn’t the same as climbing another.

You’ll make mistakes while doing this, so just accept that fact now. Excuse any mistakes with quick explanations about “a quirk of fate” or something along the lines of a surprisingly strong wind that wasn’t blowing the last time.

So yeah, he's absolutely calling out the whole "crossing a bridge" or "walking across an icy river" analogy, but he's trying to play off this ruleset as being something special because if a Cypher character comes back to the bridge two

Experience Points

Original SA post Cypher System Corebook, part 3Experience Points

One of Cypher’s touted features is that it does not give the players experience for killing monsters. Rather, the GM is free to hand out experience whenever/however they like (with guidelines), and specifically through a mechanic known as GM Intrusions.

I'll talk about GM intrusions later on, but the short version is that whenever the GM wants to introduce a twist or a complication, supposedly for the sake of making the game more interesting or dramatic, he declares that he's using a GM Intrusion. In exchange having their plans fucked around with, the player earns 1 XP themselves and then nominates a different player to also earn 1 XP.

The first thing I want to mention is this sidebar from the book:

quote:

Defeating opponents in battle is the core way you earn XP in many games. But not in the Cypher System. The game is based on the premise of awarding players experience points for the thing you expect them to do in the game.

Experience points are the reward pellets they get for pushing the button—oh, wait, no, that’s for rats in a lab. Well, same principle: give the players XP for doing a thing, and that thing is what they’ll do.

In the Cypher System, that thing is discovery.

The first two paragraphs are not wrong. If you reward players for doing A Thing, then in general they’ll keep engaging in that behavior because you’re rewarding them for it.

It’s that last sentence I take issue with, combined with statements like these:

quote:

The core of gameplay in the Cypher System—the answer to the question “What do characters do in this game?”—is “Discover new things.” Discovery makes characters more powerful because it almost certainly grants new capabilities or options, but it’s also a reward unto itself and results in a gain of XP.

The generic idea that players will engage in whatever behavior you reward them experience with is correct, but I don’t think it necessarily follows that just because you tell the GM to reward the players with XP for engaging in discovery and exploration, that you’ve also made a game that’s tailored for discovery and exploration.

By stripping away the experience gain from monsters and telling the GM that they can award XP for whatever they like*, you create the conditions to have games that can be exploration-focused, but you’re not making a game that’s specifically made for it.

*that in itself is yet another potshot at D&D-type games, but omits the fact that Dungeon Master Guides since AD&D 2nd Ed have been telling DM’s to award experience for all sorts of things beyond just killing monsters, and even before AD&D 2e, players would gain experience for retrieving treasure from dungeons , which is exactly the kind of hard, written rule that directly encourages players to engage in a specific kind of behavior. Even if you don’t tell the DM that they should reward the players for looting the bejesus out of that dragon’s lair, it’s going to happen regardless.

The waters are further muddied when he gives out other guidelines for handing out XP:

quote:

Sometimes, a group will have an adventure that doesn’t deal primarily with discovery or finding things. In this case, it’s a good idea for the GM to award XP for accomplishing other tasks. A goal or a mission is worth 1 to 4 XP for each PC involved, depending on the difficulty and length of the work. As a general rule, a mission should be worth at least 1 XP per game session involved in accomplishing it. For example, saving a family on an isolated farm beset by raiding cultists might be worth 1 XP for each character. Of course, saving the family doesn’t always mean killing the bad guys; it might mean relocating them, parlaying with the cultists, or chasing off the raiders.

quote:

Players can create their own missions by setting goals for their characters. If they succeed, they earn XP just as if they were sent on the mission by an NPC. For example, if the characters decide on their own to help find a lost caravan in the mountains, that’s a goal and a mission. Sometimes character goals are more personal. If a PC vows to avenge the death of her brother, that’s still a mission. These kinds of goals that are important to a character’s background should be set at or near the outset of the game. When completed, a character goal should be worth at least 1 XP (and perhaps as much as 4 XP). This encourages players to develop their characters’ backgrounds and to build in opportunities for action in the future. Doing so makes the background more than just backstory or flavor—it becomes something that can propel the campaign forward.

So it's an exploration-focused game, except if the players are dealing with a particular non-exploration-related mission, you should award them some XP for successfully accomplishing it. Further, if the players come up with some objective that they want to do all their own, you should also facilitate that and again give them XP for successfully accomplishing it, again even if it's not exploration-related.

But Cypher/Numenera is a discovery-focused game because Monte Cook said so. Okay.

It's a much more useful general guideline when he says that during a typical session, a player might earn 2 to 4 XP, and then earn another 2 XP between sessions.

which will bring us to the next bugaboo of this game: Spending XP

(I'm breaking up these posts into smaller chunks so that there's a central thesis to every mechanic I'm discussing)

Spending XP

Original SA post Cypher System Corebook, part 4Spending XP

Just as the game tries to innovate on how XP is awarded, it also tries to innovate on how XP is used. That is, it's not just used to advance in

You can spend 1 XP to reroll any result. You can go back and use the first roll if that was better, or you can even use more than 1 XP to reroll the same task multiple times.

The fact that you can spend XP by itself carries certain design issues, but this use of it in particular is interesting to say the least. We established previously that a player should supposedly gain about 6 XP per session, and now you’re spending a sizable chunk of that and you’re not even guaranteed that it’s going to work. To compare, there’s a Military Occupational Specialization mechanic in Night’s Black Agents where you can invoke a once-per-session automatic success for one specific skill that you’re specialized in, and even that says you can’t use it to automatically succeed at something supernatural.

To bring it back to Cypher, by its own description not even a task difficulty 10 should be able to defy physics, so there is by implication a similar limitation even if you used this 1 XP feature to automatically succeed at a task, and you’re spending a precious resource to do it.

You can spend 1 XP to prevent the GM from making a GM Intrusion. One exception to this is when it comes to certain Descriptors, when the GM can make an Intrusion based on your Descriptor and you cannot prevent it by spending XP.

You can spend 2 XP to declare that you're skilled in a particular something for the short- or medium-term. In keeping with what I've said earlier about Cook's hangups regarding setting target numbers:

quote:

She spends 2 XP and says that she has a great deal of experience in using these. As a result, she is trained in operating (and breaking into) these computers. This is just like being trained in computer use or hacking, but it applies only to computers found in that particular location. The skill is extremely useful in the facility, but nowhere else.

Medium-term benefits are usually story based. For example, a character can spend 2 XP while climbing through mountains and say that she has experience with climbing in regions like these, or perhaps she spends the XP after she’s been in the mountains for a while and says that she’s picked up the feel for climbing there. Either way, from now on, she is trained in climbing in those mountains. This helps her now and any time she returns to the area, but she’s not trained in climbing everywhere.

This last use of XP I’ll let the book speak for itself:

quote:

In many ways, the long-term benefits a PC can gain by spending XP are a means of integrating the mechanics of the game with the story. Players can codify things that happen to their characters by talking to the GM and spending 3 XP. For example, a character named Jessica spends a long time working in a kitchen in a restaurant that she believes is owned by a man who works for shapechanging spies from another planet. During that time, she becomes familiar with cooking. Jessica’s player talks with the GM and says that she would like the experience to have a lasting effect on her character. She spends 3 XP and gains familiarity with cooking.

Other examples include conjuring an NPC contact, buying the TRPG equivalent of player housing, a title or job, wealth, or an artifact.

And then finally the more traditional use of XP as a means of progressing a character’s tier, except even this isn’t designed traditionally. You spend 4 XP to gain one of these features:

* 4 points to add your stat pools

* Add 1 Edge to any single stat

* Increase your Effort by 1

* Either become Skilled at something (reduces task difficulty by 1) or Specialized at something you’re already Skilled at (reduces task difficulty by 2)

* Reduce the speed penalty for wearing armor by 1

* Add 2 to your Recovery rolls

Once you’ve acquired 4 of these features (or a total of 16 XP), you go up one tier. That unlocks a bunch of new special abilities based on your Role and Focus, and then you get to start over again with acquiring these 4 features.

Normally, I’m all for “bennies” that players can spend to make rolls that they really want to succeed at, or to exert narrative control over the story, or to pull a rabbit out of their hat when they really need it, but putting it on the same level as the stuff you need to advance your character in tier just seems both awkward and punishing. I’m not going to dwell on this too much because most reviews of Numenera, including Tulul’s own F&F, have already talked about this, so instead I’m going to talk about how right after this Experience section, we get to the Optional Rules chapter, and nothing happens.

That is, Numenera was released in 2013. The Strange was released a year later. The Cypher System Corebook was released this year. The two preceding games already had these issues: having to spend points from your pool and having the pool represent your health didn’t sit well with some players. Having to spend XP to gain in-session benefits fought against wanting to bank XP to level-up your character didn’t sit well with some players. But they never tried to address these issues, even as optional rules.

I can see that they merged and imported material from both Numenera and the Strange and their respective supplements into Cypher, but there’s still no mention of what might be done with regards to these fairly divisive design elements within the games.