Warhamster Fantasy Roleplay Renegade Crowns by Falconier111

Introduction and Chapter 1: Geography

Original SA postNight10194 posted:

The Border Princes' take on the lure of power and the perceptions of 'strongmen' is fun!

Oh hey!

People get into tabletop RPGs in all sorts of ways; they were introduced to them by a friend, encountered them in a game store, or found a rulebook in a bookstore that grabbed their interest. I got into them through a version of the last method: I found a copy of GURPS Space in a Barnes & Noble, saw tables in the back for randomly generating planets and alien species, and immediately snapped it up because I was and am the kind of nerd to spend hours rolling on those tables. I’ve loved doing that sort of thing ever since, so when I heard someone dedicated an official sourcebook to that, I had to download that shit. And now that I have nothing to do during the quarantine and because I do what I want, I get to show it to you.

Part 1: Introduction and Chapter 1: Geography

For those of you unfamiliar with the more obscure parts of the Warhammer Fantasy world, the Border Princes (refer to it as one thing with a plural name, i.e. the United States) is the name of a miserable stretch of badlands way to the south of where most games take place, stretching between the borders of Bretonnia, Tilea (fantasy Italy), and a gigantic stretch of even less hospitable land mostly occupied by orcs. It’s kind of a dumping ground for everyone in the setting who’s desperate enough to choose the worst possible place to resettle without having to face down actively hostile governments. Before they released Renegade Crowns, they’d established elsewhere that politics and society in the Border Princes were a swirling mess of civil war and counter-coups that made the systematic approach they’d used in other regional sourcebooks impossible, so the authors just dedicated half the book to methods to randomly generate a campaign setting in the region and the other half to DM advice for using that setting once you put it together. As we’ve seen in the thread, official Warhammer Fantasy adventures are kind of shit, but Renegade Crowns takes the opposite approach; it gives you a toolbox to use to generate a campaign from the ground up, providing players with a clear goal (taking the place over), plenty of story hooks, and an interconnected world the players can wedge themselves into as it moves around them. Having used them multiple times, the results you get from these tables just seem to mesh naturally and create something interesting every time.

So that’s what I’m going to do with this review (for the first half of the review at least). I’ll take you step-by-step through the process of creating a region, exploring its quirks and elements as we go, before illustrating how the second half of the book gives you tools you can use to make that setting playable.

Before we begin, I should establish a few things that characterize the Border Princes, just so we can all be on the same page:

- The land here can barely support agriculture or pastoralism, so populations are low and stakes are high. Resources are desperately rare here compared to anywhere else in the world.

- As far as the book is concerned, the Border Princes has no native population (the Warhammer wiki mentions a few principalities with Greekish names, but Renegade Crowns never references them, so I do now.) Most people in the area are either immigrants from the rest of the world or their children and grandchildren. Since nobody goes there unless they have no other options, the Border Princes is a hive of scum and villainy populated mostly by criminals, opportunists, and oppressed peasants.

- These conditions create an excess of population and deficit of land, making bloodshed an always viable option when it comes to survival. If you’re familiar with pond ecology, think that on a societal scale and you have it about right; people are constantly fighting, murdering, betraying, and undermining each other, with nearly every ruler coming to power after killing their predecessor and dying to their successor. However, the presence of orcs, Chaos worshipers, marauding undead, and local monsters keeps them from getting too involved in mutual murder, leading to cooperation between people who hate each other.

- For a place that’s kind of a gigantic shithole, the Border Princes has a long and complex history. It’s kind of a graveyard of empires; the area’s seen invasions from Nehekhara (fantasy ancient Egypt, eventually became the Tomb Kings), Araby (fantasy, well, Arabia), and Bretonnia, all of which ended up vanishing into the badlands. Combine the stuff they left behind with dwarven ruins, the aftermath of Chaos activity, and weird crap with no obvious origin and you have some wild stuff hiding out in the hills.

- The Border Princes is characterized by those titular princes: a variety of exiles, strongmen, and would-be rulers who constantly fight for control. No matter how powerful they are, everything they work for will have vanished within a few generations their tests. Any Prince you generate has something like a one-in-20 chance of rising through a peaceful transfer of power instead of some flavor of murder; any government in the region lasting more than three generations is literally unheard of. If there’s a single theme running underneath any Border Princes campaign, it’s a failed interplay of trust and power; in order to come to power, a prince has to surround themselves with figures they can trust to carry out their will, but trusting anyone opens them up to betrayal and probable death. “Futility” might also be another underlying theme, since nothing’s going to last more than a few generations anyway. Everything in the Border Princes is temporary, including anything the players achieve. The book straight up says changing the status quote of the Border Princes is impossible. Instead, the PCs are looking for temporal power and wealth, regardless of what it might bring next – tying them neatly into the cynical themes others in the thread have pointed out underlie Warhammer Fantasy.

- For the obligatory fluff text, Renegade Crowns tells us the story of one Ilsa, a traveler-turned-Prince, and a bunch of little asides scattered throughout the book. They are kind of generic and spread out, so I’ll summarize her story for you here; she arrives in the Border Princes, complains about the conditions a lot, backstabs her way into power, and dies resenting the guy who backstabbed her. Awesome!

We good? We good. Let’s go.

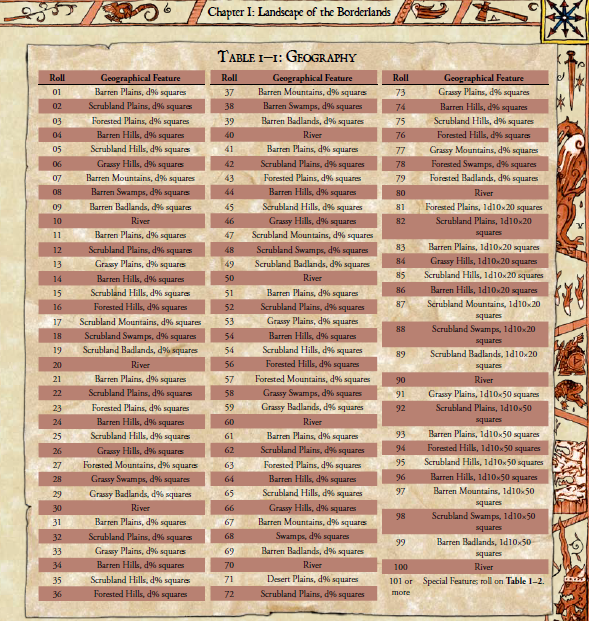

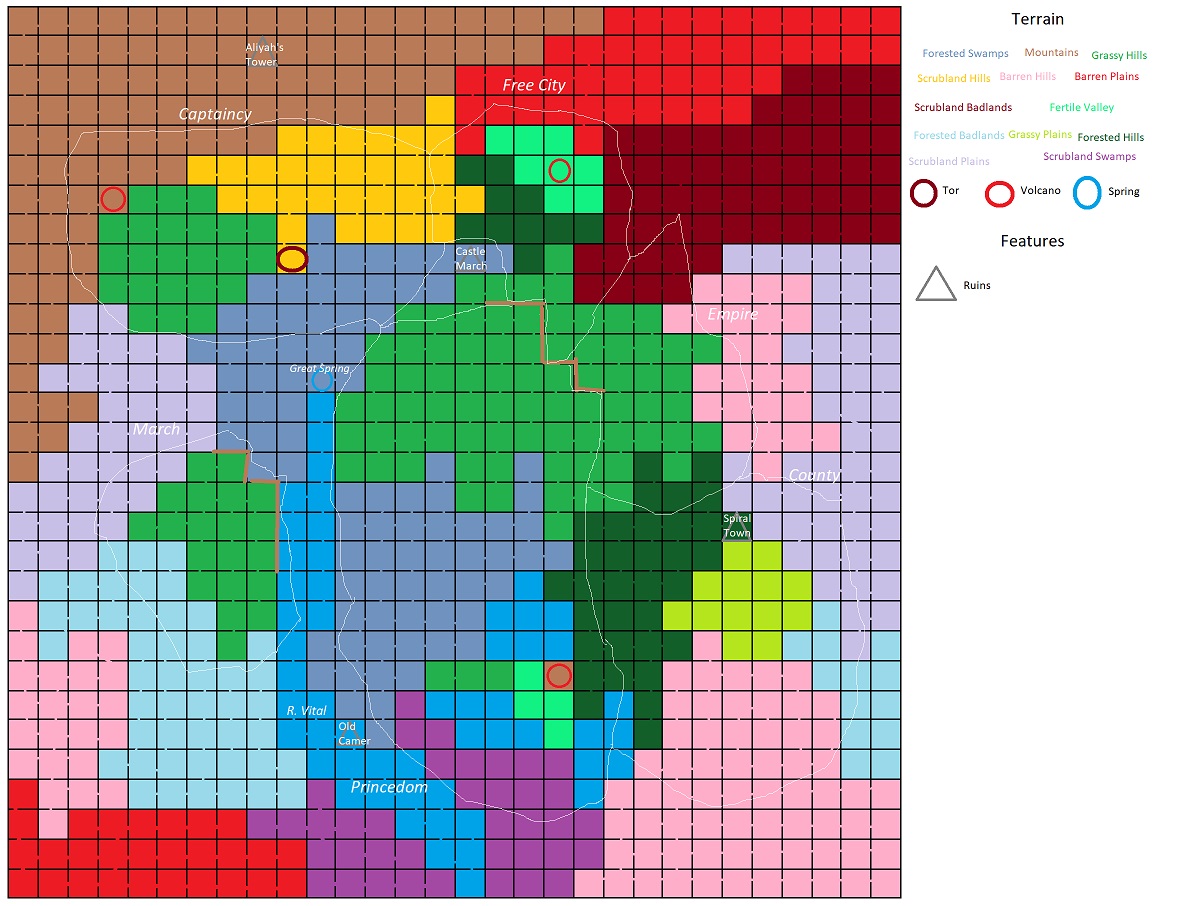

So the first stage of building the campaign map is laying out a grid. Exciting! The book recommends a 20x20 grid for first-time cartographers but I’m going with 30x30 because I’m a badass. This shall be the beginning of the wonderful road we will travel together, guided along the way by my terrible skills at MSPaint. Way this works is I’m going to make a bunch of rolls on this chart:

Yes, all the charts look like this, but this is one of the biggest. Also, check out that border art!

Each pair of d100 rolls will give me a terrain type and how many squares to fill in with it. Each terrain chunk has two parts: terrain type (badlands, which are so rocky they make farming impossible; hills, which are gentle enough to support animal husbandry and some farming; mountains, which are mountains; plains, which are flat enough to farm or easily traverse; and swamps, which are wet, inhospitable, and generally suck) and vegetation (barren, which means desert, unbroken rock, or terrain uninhabitable for some other reason; scrublands, which are too poor to support human settlement but not borderline impassable; forested, meaning the area has enough trees to supply settlements with wood, forage, and also evil goat people; and grassy, which means the area is actually fertile enough to (in theory) support respectable agriculture). You can also get rivers, which the GM has freedom to draw out as they like, and a variety of unique features. Every time you roll on the chart, you add 10 to the next roll until you get a special feature, after which it resets. You just keep going until each map square (which, by the way, represents 16 mi.², or length-wise about the distance you can travel in a day over local terrain) has something in it.

(By the way, I won’t be going this in-depth in the process in the future; right now I’m showing you the basic structure this all runs off.)

Now, while this looks complicated and time-consuming at first blush, that’s because it is. It isn’t actually that difficult a process but building a map does take a while. If you take a close look at the chart (don’t bother, I did it for you), you will notice the results can make you fill in awkward numbers of squares at the same time, place terrains in ways that don’t make geological sense, and leave you with more terrain than the map can fit. They address these issues all at once with my single favorite section in the book;

Renegade Crowns posted:

The first four chapter of this book contains a lot of random tables. Indeed, it consists almost entirely of random tables and guidelines on how to use them. These tables are provided purely to help you create a setting for your campaign. You should ignore the results generated by the tables whenever you have a better idea. If you don’t like the result of a roll, re-roll. This is not “cheating.” This is not even “misusing the book.” This is what you are supposed to do with this book.

One of the hardest parts of creating a campaign setting is filling in the necessary background for the areas where you don’t have great ideas. Use the tables for that. Sometimes, coming up with a great concept is equally difficult, and you can just use the tables and see what the results inspire. However, the tables are there for you to use when you do not have plans of your own. If you have ideas, ignore the tables completely. If a result gives you an idea, ignore all the sub-tables and just put it in.

The tables exist to make your life easier, not to restrict what you can write. Use them as such.

Hell. Fucking. Yes. Most books that make use of random tables heavily urge you to use results-as-rolled, no matter how much they might clash; they usually rationalize it by pointing out that reconciling contradictory results is a great way to spark creativity. This is true and I have never once failed to fudge a roll a roll to get a more interesting outcome. This is the first time I’ve seen a book acknowledge that, and my first time through I fell in love over the course of three paragraphs. I will make copious use of this principle in the rolls ahead.

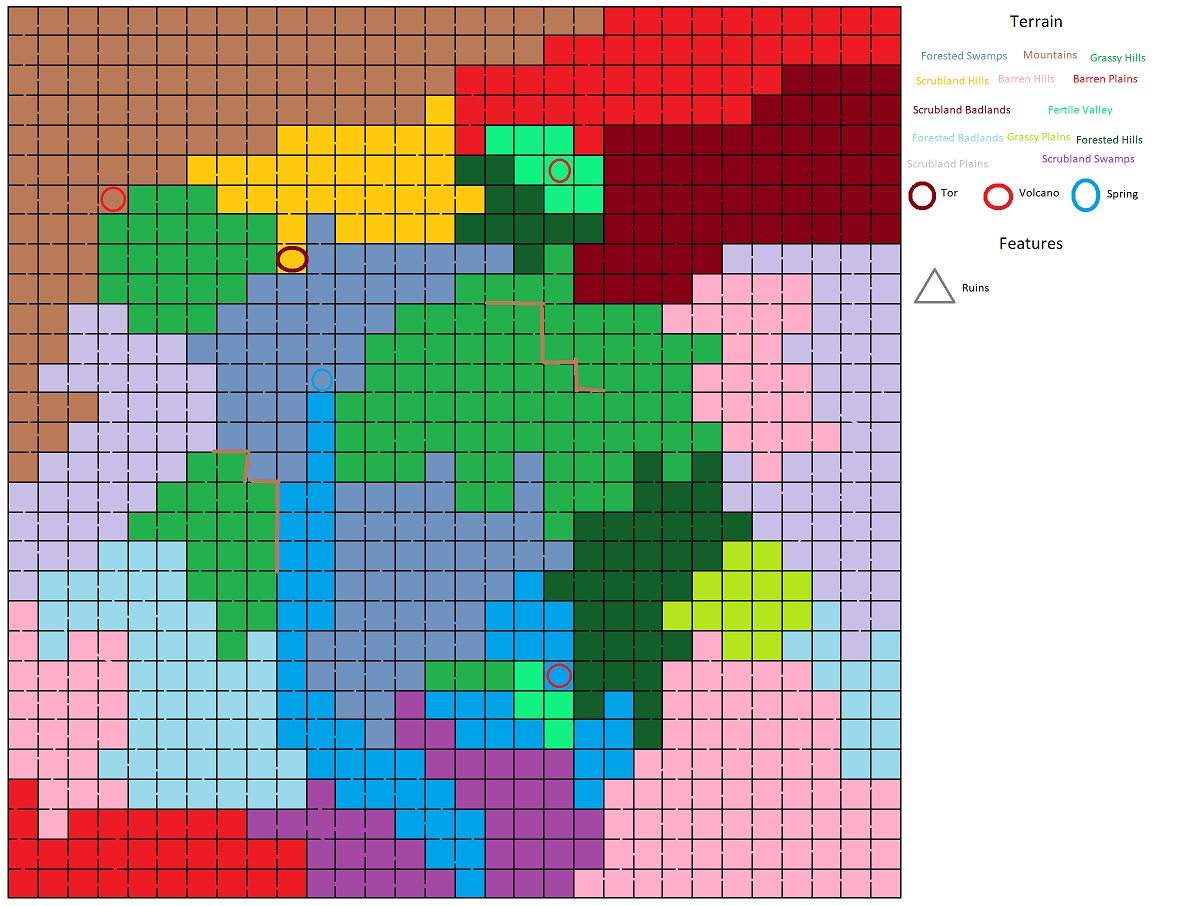

Behold! The land of Camet!

Some notes on the map:

- I know this map isn’t especially pretty, but I don’t care.

- I am in awe of how fertile this region turned out to be. I mean, I did fudge a few rolls, but I didn’t touch the rolls that gave me grassy hills and plains. Usually a map this size has maybe half as many agriculture-suitable squares. By Border Princes standards this place is practically paradise.

- Rivers are (I think) supposed to be just long lines, but I find place names tend to fit awkwardly over hand-drawn borders so I usually just treat rivers like any other terrain type, just following a course instead of laid down like other types. Is there a better way to represent them so it doesn’t look like this river is multiple miles across? Probably. Just imagine the river runs down the middle of those squares and each side has the same terrain type as its neighbors. Also, I ended up fluffing this river as prone to extreme seasonal flooding, so I guess blue squares represent those areas underwater at the river’s height.

- A tor is a tall hill with one accessible path up it and a fertile valley represents farmland that’s up to the standards of the rest of the world; both of those are prime locations for urban settlement and will probably be where any towns happen to pop up when we get to that stage of map generation. I’ve never seen that many in a map this size though, holy crap, this map.

- Those brown lines represent high cliffs. They aren’t labeled as such in the key because I forgot and only noticed it as I was uploading this post, and like hell am I going to rejigger the layout of all the maps I’ve made for this review to fit one relatively-obvious element in.

- I didn’t just lay these sections out on the map in order of when I rolled them; I organized my results to more-or-less evenly space inhabitable areas around the center and fill the areas between them and the sides of the map with more hostile terrain. This will give future princes enough space to hold a core territory and struggle to take over their neighbors while leaving room for monsters and ruins. The results may not be geologically sensible, but the book tells us this is common in the Border Princes and also see the first bullet in the list.

Oh, speaking of ruins, that’s the next step in the process. Scavengers and desperate locals either destroy or reoccupy most abandoned structures and settlements in the Border Princes, but a few ruins and up being left untouched; these usually have some kind of supernatural menace haunting them scary enough to keep out interlopers. Ruins fill the role of dungeons, providing places a party might explore to either have a break from local politics or fish out something useful to use in their quest for regional domination. Renegade Crowns HEAVILY encourages you to fiddle with the results you get in this stage, since the results you get this early in the process say a lot about the region and its history: not only do they tell you who’s been through the area and why, but they imply what the tone of your campaign might be; more ruins means adventurers and supernatural elements are more likely to show up, while fewer ruins in the area makes for a more mundane and politically-focused game. I rolled a modest number of ruins in the area, so I guess this map offers a bit of both.

Five elements define each ruin: type, ancient menace, original purpose, reason, and age.

- Type: the culture or group that built the ruin. The book describes how each group built their structures, a ruin’s aesthetics, and what generally happened after they abandoned them, covering multiple human cultures, dwarves, cultists, and the occasional Border Princes oddities (everything from ruined magic universities to displaced buildings from halfway across the world to things like ruined versions of a party member’s hometown).

- Ancient Menace: the reason why the ruin hasn’t been dismantled yet, with rolls modified by the ruin’s type. These range from supernatural threats like demons through nebulous plot devices down to hillbilly stereotypes (or a one in 20 chance of nothing). The book refuses to define any of these threats beyond what they are and speculation on how you use them, pointing out that a GM probably knows what’s best for their region more than a bunch of random tables. It also provides advice on how these threats might influence the region if they escape the ruin/the GM wants to mix local politics up.

- Original Purpose: what kind of building or settlement the ruin used to be, such as a settlement, fortification, or religious structure, with the roll also modified by type. Curiously, Ancient Menace and Original Purpose aren’t connected; you’d think, say, that undead would be more likely to show up in a tomb, but I guess they decided to simplify rolling. Sensible enough. Also curiously, oddities have no entry on this table, which also makes sense since they are supposed to be inexplicable.

- Reason: why the ruin ended up abandoned. This section is pretty mundane, just covering stuff like civil war or natural disasters or resource exhaustion, with a small chance of getting something supernatural. This is the only table not influenced by the ruin’s type AND the only one to use a D10 instead of a D100.

- Age: when all this took place. This is the only subsection to not use random rolls; instead it includes a timeline and advice for how GMs might slot the ruin into the region’s history.

Once you finish rolling up your ruins, you’ve completed the first quarter of region generation and are ready to start generating actual Princes of the Border Princes. So let’s do that.

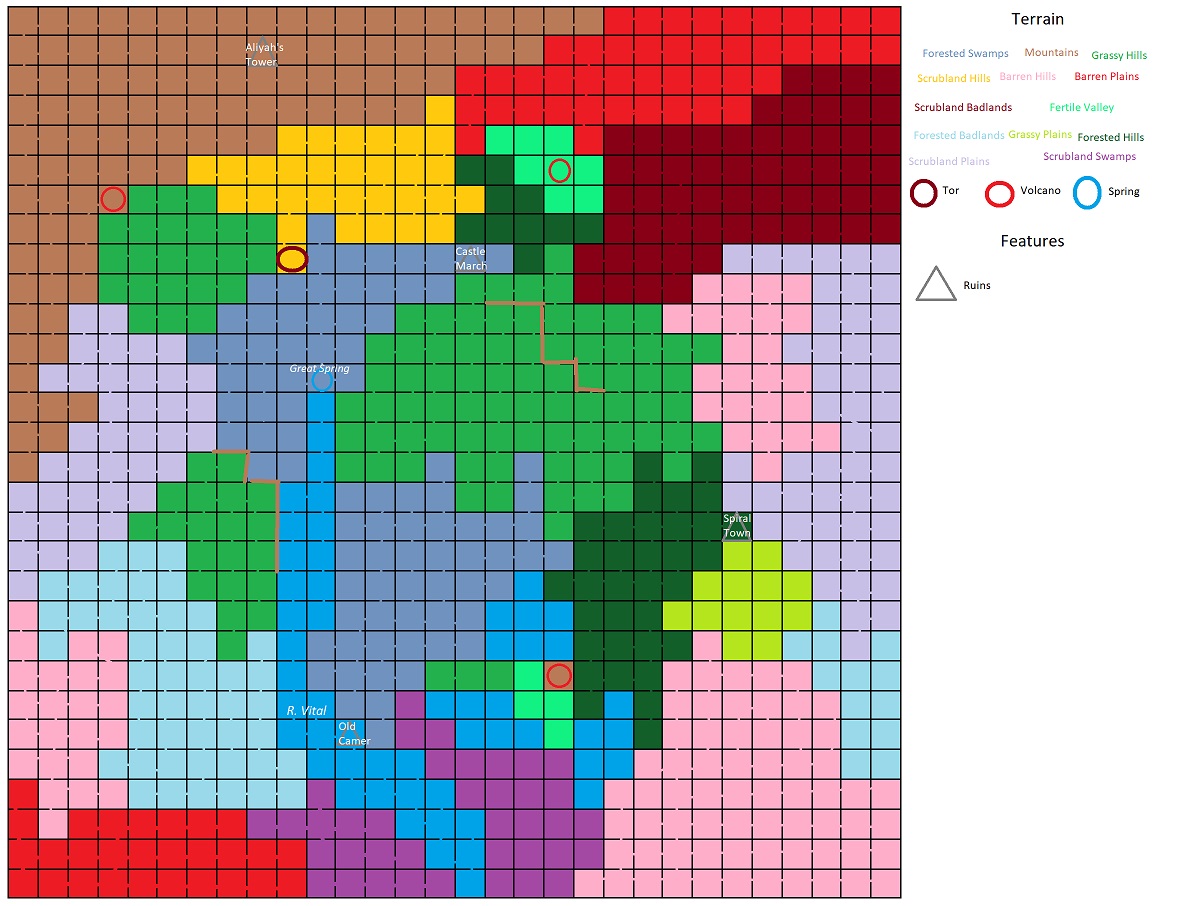

Through the magic of d100s, map labels, and yet more mediocre MSPaint art, we now have a completed terrain map of our new region – and with it, and idea of its history. Let’s go down the list:

- Old Camer (Khemri, Undead, Fortress, Natural Decay, ~1500): When the Nehekarans first conquered the land that would become the Border Princes, they mostly simply installed satraps that governed and taxed the local populations; the ruins most Cametians call Old Camer were a rare exception. Settled by excess population from the capital city of Khemri (from which the ruins and region both get their names), Nehekharan Camet thrived for centuries, its Khemri immigrants farming the floodplains of the River Vital and freely mixing with the hillfolk who inhabited the region before them. When the Nehekharan civilization declined and pulled back within its borders, Old Camet remade itself as an independent culture and thrived for centuries, only for the Great Spring to become more erratic and permanently flood the River’s banks. Old Camet collapsed under the weight of its own population with its primary food source gone. At some point, a priest (now a folkloric figure called Old Rags) smuggled the secret to raising the dead out of their homeland to make tireless workers and enforcers for the collapsing state, but the presence of undead monsters only sealed the country’s doom and hastened its population turning on it. These days the city has nearly vanished into the swamp, marked only by scattered rubble and skeletons failing to dredge the area out; the only intact structure is the city’s former Citadel, still guarded by the undead. The Khemri have long since vanished as an independent people, but they left their mark in place and personal names among their descendants. To this day, those descendants pass around rumors of the fabulous riches hidden in the old fortress.

- Al-Misra/Spiral Town (Arabyan, Plague, Settlement, Policy, ~600): The Arabyans also built their own city when they arrived in Camet; the locals now call it Spiral Town, since even centuries later visitors can see spiraling minarets over the city’s crumbling walls. Compared to its Nehekharan predecessor, Al-Misra was a modest town of herders and foresters, but it housed one unique feature: a small outpost of a major Arabyan wizard society. This outpost proved the town’s doom. Around 600 years ago, some foolish mage summoned a Daemon now called the Spirit of the Mountains into that order’s enclave. The plague it promptly released ravaged the city, emptying it of population within a week. Instead of trying to reclaim the city, Araby opted to abandon the region and focus its forces elsewhere; after sealing the Daemon away, they left Camet to its devices.

- Castle March (Recent Human, Daemon, Fortress, Civil War, ~50): After they left, Camet sank into the standard cycle of decay that characterizes the Border Princes. But part of that cycle is the occasional strong personality that can unite a region. The last Prince to unite Camet was a Bretonnian noblewoman called the Marquise who ruled her domain out of a fortification she dubbed Castle March. As is also the pattern, when she died after a quarter-century of peaceful rule her heirs immediately turned on each other and ripped the realm apart. At some point, one heir managed to seize Castle March before the others formed a coalition to take her down; as they mounted a final assault on the walls, that heir revealed her trump card – she had somehow found and compelled the Spirit of the Mountains to fight for. It killed all her foes before turning on her and slaughtering every person in the fortress. If someone were to defeat the Spirit and reclaim Castle March, they would hold possibly the single greatest stronghold in Camet. But until they find a way to do so, the castle sits abandoned, leaking corruption and plague into the surroundings.

- Aliyah’s Tower (Arabyan, Weapon, Outpost, Magic, ~600): If they want to do so, they probably ought to start here. As Araby pulled out of Camet, they deployed several elite members of the same order that produced the Spirit to seal it away. They fought it up and down Camet until they lured it into the distant tower of one Aliyah bint Yasmin, the only mage to survive the fall of Al-Misra. Every other wizard there died in the struggle to contain the Daemon before she finally sealed it away. After that, Aliyah disappeared into the Cametian populace, later being made into a folk hero who hunted mutants and cultists of Chaos. Most people in Came know the story, but the details – the location of the tower, how the Spirit was sealed, the actual fate of Aliyah – have long been lost. Finding them again could change the course of Cametian history.

And we’re done with the intro and chapter 1! Next up on the docket is generating the princes themselves, followed by laying out their domains and scattering monsters in for flavor. I have no idea how much space each chapter will need, so we’ll see how everything fits together when we get there.

Prince Generation

Original SA post

Chapter 2: Prince Generation

Its princes define the Border Princes both figuratively and literally. “Prince” is a generic term here, as in principality; they rule more or less independently as petty lords, whatever their titles. And they do have titles, usually pretentious ones. As the characters the PCs will most likely focus on, each Prince gets an extensive list of traits, features, and relationships that describes almost every aspect of their character; no other section in this book goes nearly as in-depth. A Prince controls maybe an average of 60 squares, meaning almost every map has extensive areas outside of their control; this is by design, since it leaves lawless areas for monsters and border settlements. As such, unless you roll up an obscene number of princes, you’ll end up with plenty of room on your map (and you shouldn’t use too many princes, since you have to decide what their relationships with each other are and that workload increases exponentially). Renegade Crowns tells us that every region borders other regions whose princes might interfere with them despite not being present on the map, but since it gives us no rules for working with that I tend to ignore it and just make the region hard to access (that’s why Camet’s borders are mostly barren or mountainous). It also tells us that princes frequently band together, maintaining their individual characters and principalities but sharing foreign relationships, something I’ll make use of for the

six princes I generate. Six is actually a pretty respectable number; a Prince is characterized by no less than 11 descriptors (original profession, race, experience, goal, principles, personality, quirks, dark secrets, court size, title, and relationships with other princes (each of which has its own set of values)) and I’ll have to generate all of those for each Prince. Cutting down on the number of diplomatic relationships I have to juggle will make this much easier.

six princes I generate. Six is actually a pretty respectable number; a Prince is characterized by no less than 11 descriptors (original profession, race, experience, goal, principles, personality, quirks, dark secrets, court size, title, and relationships with other princes (each of which has its own set of values)) and I’ll have to generate all of those for each Prince. Cutting down on the number of diplomatic relationships I have to juggle will make this much easier.The first step (and one of the most important) is determining what the Prince did before they became a Prince, since it determines their general approach to rulership.

- Bandit: someone who did banditry professionally. Pretty obvious. A bit less than one in three princes started out as bandits. They usually come to power violently and get deposed quickly since they rarely have management skills, and they govern in one of two ways; they either operate like they did as independent bandits, using intimidation and violence to make themselves rich, or they try to puff themselves up and present themselves as glorious rulers with grandiose titles. The second approach tends to work better; bandits who try and lay out courts often end up actually thinking about what rulership entails.

- Knight: someone who tries to emulate feudalism in their principality and their person; maybe one in five princes fall into this category. Though they tend to look down on their neighbors and hold to unrealistic moral codes (neither of which is mechanically represented, but whatever), there are often the most successful type of prince, since their warrior ethos and habit of drawing out legal codes like whatever feudal society they’re emulating makes for stable and well defended realms. Even if their predecessor wasn’t a knight, anyone who inherited their throne peacefully might qualify as a knight mechanically (yes, princes have stats given, I’ll get to them in a bit) since they’d use the same methods as any other knight. Knights also tend to adopt more modest and feudal-style titles.

- Mercenary: a professional fighter who transferred from controlling a band of other professionals to controlling a principality. More than a third of all princes fit in this category, more than any other. These guys usually come to power after either getting stiffed and taking their payment in blood or just using their employees for a Klingon promotion. Most mercenary( tend to run their territory on military lines, with an emphasis on rank and a chain of command, but those that last often drift increasingly towards a knightly rulership style. Most don’t last that long; administering a territory is very different from administrating a military unit, so they often end up deposed the moment they lose control. Mercenaries usually adopt military sounding titles, though they are just as prone to self-aggrandizing titles as everyone else.

- Merchant: people here to get rich, together holding maybe 1/20 of the principalities in the region. These guys are the worst of the worst; either they came to the Border Princes fleeing creditors or because they thought conditions there were optimal for making bank without need for morals or ethics. They usually come to power through money (whether by paying off mercenaries or a prince’s followers) and maintain their position by employing mutually-antagonistic mercenary groups and making regular payments. Before an outside force dethrones them or some mercenary inevitably decides to move in, they tend to run their holdings as particularly exploitative businesses and claim medieval-European-urban titles (like mayor or guildmaster).

- Politician: anybody who rules through anything other than violence, clocking in at one in 25 princes. These guys usually start out as advisers and courtiers or heirs to previous rulers and control their lands through manipulation and politicking. They never shun violence – this is the Border Princes – but rarely fight directly (which is what separates them from almost every other type of prince). Most politicians’ principalities end up pretty stable if they can take the throne their predecessor already laid the groundwork, but unless they can master military action they often let their military decline enough that their neighbors take over.

- Priest: one in 25 princes actually qualifies as a religious figure. Less likely to be on the run from justice or native to the area than almost any other type, priest princes are usually fanatics of some warlike god trying to prove themselves or spread their god’s influence; most priests can probably find a niche elsewhere, and anyone else dumb enough to come to the Border Princes rarely has the competence they need to take power. Most priests keep their actual titles from their religious hierarchy and don’t puff themselves up much.

- Wizard: yes, one in 50 princes are actually professional spell casters. Wizards tend to be rare in the Border Princes anyway – better opportunities elsewhere, y’know, and that’s if they aren’t running from witch hunters or something – and those that do try to seize power struggle with a mistrustful population unwilling to trust them with power. Those that do seize control tend to stick around since magic is rare in the region and intimidating enough to keep neighbors at bay. Wizards tend to rule small territories (since they don’t have the administrative skills and charisma necessary to take over larger areas) and tend to take a lofty title with some magic adjectives slapped in front of it.

Their culture of origin also influences princes, obviously; from most to least common:

- Border Princesers (?) are properly cynical and aware of local conditions, usually more successful than princes from other cultures (though they still make up less than half the total);

- Imperials often try to emulate their homeland as much as possible, instituting Imperial institutions in miniature (even when that’s a bad idea) and naming their capital after some important Imperial city (this is common enough that locals differentiate between villages with the same name by attaching insulting adjectives);

- Bretonnians usually drift towards aping knighthood, including granting their followers teeny fiefdoms and elevating their own Grail Maidens (the locals call them Drinking Harlots, mostly because it’s an accurate title);

- Tileans try to re-create the Renaissance Italian culture they originated in with a mercenary culture flavor (since most started out as mercenaries), though they rarely make any kind of headway in the culture or prosperity departments;

- Humans from other regions basically have their origins and behavior left to GM approval, though the book kind of implies they’re from Estalia (fantasy Spain) or Kislev (fantasy Russia);

- Dwarves occasionally come down from the mountains to try and reclaim some lost mountainhold and are the most likely to have some official backing;

- and Elves and Halflings occasionally come to power, though they’re so rare it’s hard to generalize about their behavior. According to the stereotype, all elves are wizards (untrue, though Elven princes usually encourage the rumor) and “all Halfling lords want to turn their realms into a giant pie shop. This has only happened once (or so most historians claim), and Max the Glutton used his enemies, and then his subjects, as ingredients.”

.

.

While you can assume every prince is about at the same level, Renegade Crowns gives you tools to determine at what point in their lifespans/careers a given prince is, complete with career paths and stats (most princes are in their third career). I tend to ignore this section or just breeze over it since it’s tied into the system more than most parts of the book. While I’m talking about it, this book relies very little on crunch; for the most part it’s a mixture of write-your-own-fluff and GM advice. You could very easily take your results from these charts and translate them to another system. I’ve never done so, but I guess I might in the future.

After all this we get to generating a given prince’s personality. These elements aren’t setting-specific like the first two sections and boil down statless NPC generation (which it is). As such I’ll cover the individual rolls with a bit less granularity;

- Goal: not just the Prince’s immediate goal, but the sort of thing they are aiming for long-term. Staying in power and gaining more power between them make up almost half the possible rolls, but the rest are spread out between everything from making money to building a dynasty to just trying not to die.

- Principles: yes, despite the cynicism, most princes have standards. Well, you have a three in 10 chance of getting a prince who doesn’t actually have principles, but the book specifically notes they don’t tend to last any longer than anyone else. Most princes draw the line at consorting with Chaos, though a few try to stay honest, not kill innocents, or just be good people in general (and those last ones DO tend to die quickly).

- Style: how a prince usually interacts with others. Most lean towards a couple flavors of ordering people around, though you have the occasional schmoozer, businessman, or one of those people who constantly insults you and expects to be insulted back (without ordering you murdered).

- Secret: a story hook to use for undermining the Prince. These secrets range from being on the run from justice to worshiping Chaos to not actually having secrets to having done the sort of good deed that makes you look weak to your other amoral murderlords - or your having committed something beyond the pale even for warlords, like slaughtering an entire village down to the children, which if discovered would turn almost every person in the region against you. Also, you can occasionally roll multiple secrets, though the book recommends you cap the number at four before things get completely out of hand.

- Quirk: some strange aspect of a prince’s behavior not hidden and serious enough to count as a secret but noticeable enough to show up if you spend time in their presence. These aren’t supposed to be crippling or get in the way of ruling, instead adding flavor to a ruler and possibly offering a hook PCs can use to manipulate them. These include things like having an overused catchphrase, never crossing some moral line (on the scale of, say, leaving payment when they confiscate the last of a village’s stores), being a religious fanatic, or flying into a rage upon seeing a certain uncommon color.

We wrap up prince generation by determining their title and principality size. Title is pretty simple; you either choose their title or roll on a big ol’ list of 20 and use the result. To get the size of their principality, though, you roll on that very chart I showed off in the first update and portion off that number of squares as their holdings. Though you can place these wherever you want, you should probably center them on (marginally) arable land with natural borders between them and other princes, though you can do whatever you want, of course. While the book recommends rolling for principality size at the end of individual prince generation, I prefer to do it first; it lets me get a better handle on the personalities of my princes if I know what their situation is first. With all of that rolled, all your princes are now complete.

The final step of this process is figuring out what your princes think of each other. Often the princes will band together and share diplomatic relationships – the book gives you a complicated process for dividing them up fairly – but I find the results make groups of mutually antagonistic princes work like little hive minds, so I tend to avoid that method unless there’s a solid reason (for example, if they’ve been in an alliance for a long time). Each relationship has two values and one subvalue: length, type, and subtype. As you can probably guess, the first is how long a relationship’s been going on, the second is the general flavor of the relationship, and the third represents that relationship’s defining elements – say, if two princes are allied, they might be bound by ties of enlightened self-interest or by ties of sleeping together. The Border Princes being the Border Princes, the line dividing diplomatic and personal relationships is so thin it may as well not exist, so how your princes interact is as driven by personal feelings as much as realpolitik. As such there is no division between public and private feelings in these relationships; one prince having a crush on another is as valid and important a relationship as to princes playing diplomatic games, and the tables reflect this. In theory, you can roll independently for both sides of a relationship (say, if you get an Alliance result for one and a Fear result from another, the former party might believe their alliance is built on mutual respect while the other just plays along because they think the first will turn on them if they don’t), but the book recommends against this as it tends to produce “daft” results; I recommend against it because it makes relationship generation too complex and hard to jigsaw together.

- Alliance: the princes work together for a given reason. The Border Princes being what it is, alliances never spring out of mutual respect and good feeling, instead of always having some justification (provided by the subtype). These motivations run from political calculations to respect earned in battle to personal ties unrelated to their status as princes. As alliances are rare in the region, they come with a bunch of special rules; long-standing alliances need multiple reasons to keep them going, while princes rarely have multiple alliances at once (especially given how the subtypes work; RAW it’s possible to roll up an entire region’s worth of princes in a massive polyamorous relationship, and while that’s awesome, it’s not thematically appropriate).

- Bitterness: the Prince doesn’t just hate the other party; they want them to suffer for a specific reason. This means their actions revolve around getting revenge for something personal, whether the other prince executed a close relative, kicked them out of the family, or just failed to realize they were a gigantic incel.

- Contempt: the Prince’s thinks the other one is so weak they either plan to invade them, ignore them, or try to use them as pasties in some other scheme. This perception might be based on military or personal incompetence, experience, or just thinking the other party is such a goody-goody that they’d never fight back.

- Envy: not just wanting something from another prince, but specifically wanting to take it from them. Not just, like, land or material goods (though those are possibilities); they might want their skills, reputation, or just good looks. No, it being physically impossible to steal those things does not, in fact, matter.

- Fear: the Prince does whatever the other prince wants, at least until they can find a way out. Some aggressive princes try to cultivate fear in their neighbors, which can work until someone finally finds a flaw to exploit and gathers a coalition to do just that. While some flavor of military fear is standard, they might also be afraid of the other party’s knowledge or supernatural abilities (as in they are a wizard or undead, you should probably reroll this for mere mortals. The book implies this subtype only applies to people with actual supernatural powers, but princes aren’t always exactly sane and one that’s convinced (falsely) that another’s magic makes a good plot hook).

- Hatred: fuck that guy. Usually, this relationship is so intense the first prince has a hard time planning around their hatred. Chart-wise, this hatred will probably spring from some offending act, but it might also just mean that that Prince is a bigot.

- Respect: I half-lied, it is possible for princes to respect each other. If a prince respects another prince, they think that Prince is neither a threat nor a weakling; they are someone the Prince can interact with as an equal without worrying about being backstabbed (as much as is possible in the Border Princes). This might come from respect for their intelligence, family line, ability to survive, or (shockingly) because they think they’re a nice person.

- Rivalry: the Prince doesn’t have any particular feelings about the other; they’re just looking for a weakness or prepping for something else. This category has no subcategories because it’s the base state of diplomatic relations in the Border Princes. Next.

- Vengeance: like hatred, but even more specific - instead of being based on general feelings, it springs from a single offending event. It’s almost always based in an actual wrong, though that wrong may actually be way out of proportion with the vengeance they wants to take.

- War: the Prince is actively trying to kill the other (or at least take their stuff through violence). Possible causes include rolls on the envy, fear, hatred, or vengeance tables, or just wanting to conquer their land.

After you’ve rolled up and written down all those diplomatic relations, you’ve completed this stage of region creation (in theory you can work out internal politics at this point, but the book specifically advises against this; it’s a lot of work and more easily done on the fly. Thanks for the court generation section, then. Why is it here?). The last section of this chapter briefly covers how to piece together the history of your region (I’ve already done that) and then we can move on to creating individual principalities.

I’d present writeups of those princes here, but this update is long enough already and posting them now would probably double or even triple its wordcount. I’ll probably put that up as a 2.5 update in a bit before moving on to principality generation.

Princes of Camet

Original SA postMan, this has nothing to do with ponies and I am so fucking glad about it.

Chapter 2.5: Princes of Camet

Since I cut this part out to save room on the last post (a good decision), I’ll dedicate this one to showing off the six princes I rolled up for this region. As the players will spend more time interacting with/planning to overthrow these characters than anyone else, each one needs an extensive writeup. That’s what this update is. Each Prince has their various values listed next to their names in order of generation (the ones with descriptive names are results from the personality tables) and includes diplomatic relationships below, with redundant entries removed. Man, that sentence sounds technical for something that involves no math.

Every principality (in this region) is named after its ruler’s title (except for the Patrician, who rules the Free City). Each principality’s label sits outside its borders; when I generate communities, I’ll need that space inside it.

Count Dieter von Leibwald (Bandit, Imperial (Vampire), Fifth Career, By My Command, Kill the Mutant, I Wouldn’t Expect You to Understand, Open Book, catchphrase, zero courtiers): before he came to power, Dieter von Leibwald had a reputation as a particularly skilled swordsman and bandit who challenged travelers to single combat, robbing those he defeated and killing those who refuse to fight him. After he killed the previous count in a duel and came to the throne, his secret came out; Dieter came not from the Empire, but from Sylvania. He is a vampire. Granted, he’s about as weak as vampires come; he’s been known to lose fights against mortals, never come out in daylight, and refuse to transform, but you can only drain so many prisoners of blood (as is the standard death penalty in the county) before people stop questioning you. In spite of his undeath, Dieter’s managed to establish diplomatic relations with the other princes of Camet, and though no one likes him, he’s proven to particularly like hunting Chaos and doesn’t seem interested in spreading the curse – and by Border Princes standards, that makes him a lot better neighbor than many ordinary people. Visitors will find him arrogant, condescending, and deeply unnerving in person; without the need to hide what he is, Dieter enjoys playing up the vampire stereotype as a tool of fear. However, aside from his constant threats to drink his subjects dry (which he never follows through on), he’s proven himself a competent protector of his principality, attacking monsters and raiders on his own and driving them off, and he has no interest in expending the lives of his subjects to expand his territory or attack other princes. As such, his subjects, while still unhappy being under the thumb of an undying monster, consider him one of the best Counts they’ve ever had – which says a lot about the Border Princes.

- Abele and Lorenzo (Respect, Two Years, Cunning): being on opposite ends of Camet as they are, Dieter and the Tilean princes have enough room to interact diplomatically without fearing an attack or treachery. Dieter definitely likes Abele and Lorenzo more than the other way around, finding their complicated overthrow of three princes at once both impressive and hilarious; the other two keep him at arm’s length, happy not to have to deal with a homicidal bloodsucker but still willing to strike deals with him. Unless circumstances change drastically, they aren’t likely to come to blows or support efforts against the other side.

- Shashank (Fear, Two Years, Knowledge): Dieter is utterly convinced Shashank knows some secret way of killing him; though she cares little about him (he’s harder to manipulate than she could justify spending the energy on), he thinks she has it out for him and currently plots his death. He doesn’t know how she knows this nor what this method would even be, but after he drained the first two people to hint he might be wrong, no one’s pointed out the flaws in his theory. If he was to learn her secret, Dieter would immediately try to rally a coalition against her – if he could convince the other princes he was telling the truth.

- Abelard (Fear, Five Years, Personal Power): Dieter terrifies Abelard – not because of anything to do with Dieter, but because his vampirism reminds Abelard too much of his own dark addiction. He can’t think of Dieter without worrying that he, too, is turning into a vampire (untrue, but he doesn’t know that). Since the Count never tries to expand his territory, Abelard’s happy to ignore him while he campaigns in the north, just dispatching the occasional obligatory raider into his territory. Dieter, for his part, cares as a little for Abelard as he does for anyone else, but if he learned about the other prince’s secret, it might awaken something new and him; if the circumstances are right and he’s given the opportunity, Dieter may well attempt to turn Abelard into a vampire.

- Hatshep (Contempt, One Year, Inexperience): in Dieter’s eyes, Hatshep failed to prove her worth by attempting to expand her Empire after dethroning her predecessor. He sees her as even less of a threat than Abelard. For her part, Hatshep believes her magic trumps anything he could bring to the field if worst came to worst, and if she needed to do it, she could probably magically track them down and flood him with enough assassins to kill him. Unless, of course, some outside force intervenes.

Patrician Abele Columbino (Merchant, Tilean, Third Career, Marvel at My Wondrousness, My Word Is My Bond, Let’s Get to Business, Black Sheep, Uncontrollable Appetite, Eight Courtiers) and Capt. Lorenzo Bibino (Mercenary, Tilean, Third Career, It Must Be Mine, Kill the Mutant, Honestly You’d Embarrass a Snotling, Act of Virtue, Bizarre Temper, One Courtier): Abele Columbino and Lorenzo Bibino both began life in the Tilean city of Trantio, Abele as the son of the prominent Columbino merchant family and Lorenzo as a street urchin who enlisted young in a mercenary company. They met in their youth when Abele accompanied a delegation sent to hire Lorenzo’s company. Despite the fact that Lorenzo was

Abele and Lorenzo might be the happiest rulers in the Border Princes, between ruling (relatively) stable realms and sharing a loving and healthy relationship. This fact does not make them nice or good. If anything, they are the cruelest rulers in Camet, more interested in maintaining control then Dieter, less interested in keeping a good image than Abelard or Shashank, and more proactive in keeping power than Hatshep. However, the two keep each other in check enough to prevent either from crossing the line too far. When visited, the two often play bad cop, worse cop; Lorenzo will lead with his characteristic foul mouth and grow even louder upon hearing profanity from someone else (a personal quirk he’s cultivated), while Abele will play hardball with visitors implying they’d get an even worse deal by dealing with Lorenzo. Since it’s common knowledge that will Abele collects silver coins from across the world, visitors usually bring a few to make negotiations easier. Both of them are more reasonable than they appear; while Lorenzo wants power and Abele once prestige, neither feel taking advice compromises their goal and talking back (without swearing) is as likely to gain the respect as it is to pass them off. For all their power and influence, however, one major issue stalks them; the Columbinos have located Abele and are watching him for signs of greater ambition. If he was to gain enough influence to try to return to Trantio, he would throw their lines of inheritance act into chaos and weaken the house, and they’d rather assassinate him than let that happen. Lorenzo’s weakness goes a bit deeper; he runs a small network of halfway houses for what we would recognize as transgender and intersex children on the run from their parents. If someone were to discover and threaten them, they’d have Lorenzo by the metaphorical balls; he wouldn’t quite give up his life or position to protect them, but he’d compromise his own power to a large degree as long as he can keep those houses open.

- Shashank (Envy, One Year, Glorious Reputation/Military Might): for all their achievements, both Lorenzo and Abele wish they had Shashank’s title; Abele wants the prestige that comes from holding the title of Camet’s greatest leader in the last century, Lorenzo believes being the Marquis will make surrounding settlements and princes more likely to bow to them, and both think holding the title will help them rally the forces they need to take and purify Castle March, granting them the most important fortification in the region. Whether any of that is true is up to the GM. Shashank, ironically, feels the inverse; she knows the March currently has no easy way to expand and wishes she had access to their lands and resources. As long as the swamps between their borders remain impassable, however, neither side will make any moves against the other.

- Abelard (War, One Year, Conquest): Abele and Lorenzo are the only princes in Camet with the resources to challenge Abelard’s dominance; he has more land, a more stable government, and a more experienced army, but with their two towns they have an economic edge and can more easily bring their forces to bear. Outright war broke out about a year ago (more like unusually frequent skirmishes and raids, but that’s the nature of war in the Border Princes) and both sides are looking for mercenaries or volunteers. Both sides would generously reward anyone able to bring their victory, though they’d both probably order them quietly assassinated shortly afterwards.

- Hatshep (Hatred, Five Years, Prejudice): in general, the population of the Border Princes care little about sexuality; results are far more important, and Abele and Lorenzo can certainly get results. Hatshep, however, possibly due to her time spent beyond the Border Princes, is a bigot, and she’s disliked them ever since she learned of their relationship, years before they took over the three northern principalities. This naturally leads to tense relations and the accompanying border raids.

Marquise Shashank Espeaux (Politician, Border Princes, First Career, for the Love of the Children, What’s That?, You Have Our Permission to Rise, Chaos Cultist, Compulsion, 10 Courtiers): Of the various children and grandchildren of the original Marquise of Camet, only one survived the Siege of Castle March, a lesser son who settled in the isolated western hills of Camet and claimed the Marquis title. Shashank is his granddaughter, a wildly-rare fourth-generation ruler just recently come to the throne after her father’s death from food poisoning (as far as anyone can tell, an actual, natural death). Intimately aware of her status as the newest and least-experienced prince in Camet, Shashank has taken great lengths to establish a reputation as a cunning manipulator, one that’s already taken root. Unlike her father, who spent most of his reign trying (and failing) to expand, Shashank has successfully favored soft power and influence, and in time she may well come to dominate Camet diplomatically – if her secret doesn’t consume her first. As human as she seems, Shashank is in fact the product of Tzeentchian sorcery. After realizing they were both infertile, her parents turned to a cult within their principality’s border for help; they agreed in return for protection and patronage, and ever since disguised cultists have dominated the March’s internal affairs. Despite the corruption in her blood, Shashank has no interest in serving Chaos, but she values continuing the family line above escaping the cult’s influence; if she has to, she will shelter them within her borders until her death. She deliberately avoids the cult as much as possible and has taken to publicly briefly praying to any divinity that will listen, but neither of those things have helped her situation. If someone was to drive out the cult without realizing her connection to it, she’d owe them a great debt and likely work them in to her already-overstuffed court; if she believed they knew about that connection, she’d support their efforts until they succeeded in gutting it and then have them quietly murdered. If someone was to reveal that secret, both her and the March would probably be destroyed unless in her desperation she properly falls to Chaos; killing a Chaos cultist powerful enough to control a principality might be the only thing Abelard and the Tilean could cooperate on, while her own subjects would quite likely rise up in horror. The March is a ticking time bomb; depending on what happens next it may peacefully unite the region or doom its western half to destruction.

- Abelard (Rivalry, One Year): while Abelard and Shashank’s father had a tense and violent rivalry, Abelard and his successor have been at peace for her entire reign. Their relationship embodies her soft-power approach; she has combined subtly building tensions on his northern border to keep him distracted while publicly encouraging peace between two formerly hostile principalities until her efforts bore fruit. In time, given the chance, Shashank might be able to turn this relationship into a full alliance, but for now the March and the Princedom simply maintain a tense peace.

- Hatshep (Respect, Five Years, Personal Power/Lineage): Shashank and Hatshep met when Abelard brought his court wizard to the March during some rare peace negotiations between dueling leaders. They soon struck up a friendship; Shashank admired Hatshep’s magical power while Hatshep, having grown up on tales of the first Marquise’s achievements and the peace she brought to the land, saw her as her hero’s newest incarnation and offered her her support. When Hatshep turned on Abelard and secured herself a principality, Shashank offered her congratulations, and when she came to her own throne, Hatshep immediately opened up friendly relations. The two princes are too far away to coordinate any kind of joint action, but in the unlikely event of the Princedom or Captaincy-Free City collapsing, the two will likely help each other divide up the remains and possibly form an alliance of their own.

Prince Abelard de Mont Casteaux (Knight, Bretonnian, Fifth Career, This Power Is Mine, Save the Children, We’re All Friends Here, Foul Murderer, Religious Fanatic, Five Courtiers): Prince Abelard has ruled the largest and most influential principality in Camet for over 15 years, having left his old life as a petty knight in Bretonnia behind over a decade before. Outliving countless assassination attempts and perilous battles, Abelard has built a functioning state complete with a legal code and a (minuscule) bureaucracy for solving minor disputes between settlements and collecting taxes. Visitors to his court – and it is a court, even if it’s located in a small castle near his capital with only five advisors and a few servants – find him a gregarious and humble man who nevertheless never fails to impose his will on any situation he is involved in. Despite the ongoing war against the Tilean princes, Orcish and Chaotic incursions, and the standard threat of unexpected death that characterizes politics in the Border Princes, Abelard only faces two real issues. The first, and the most obvious, is that Abelard is getting old. The powerlust that brought him to the throne is growing dull as he ages and his failure to consider an heir early on has come to bite him. While he only cares so much for his principality as anything other than a path to power, Abelard has accepted his eventual death and has no desire to leave behind a pathetic legacy. His twin daughters, his only children, have proven unfit for the throne; one has devoted herself to the Lady of the Lake and spends her days praying to be made a Grail Maiden (even though Grail Maidens don’t work like that) and the other is so dissolute she’s barely fit to walk in a straight line, let alone rule a principality. In theory, he’d be open to appointing his successor, but they’d have to walk the delicate line between impressing him and not threatening him or his family. The other issue has followed him almost his whole life, and in fact caused his exile from Bretonnia. Abelard is a cannibal. He acquired a taste for human flesh at some point when fighting for his liege lord in a petty war in his homeland and that lord exiled him when he discovered Abelard had been eating the infant children of his peasants; even for Bretonnian nobility, that was too much to bear. Abelard has since cleaned up his act – not only is he horrified by what he did in his homeland, he now has a genuine soft spot for the welfare of children that endears him to his subjects. But he never lost the habit. It’s an addiction he satisfies by eating parts of criminals he executes (as far as anyone knows, he likes killing his enemies in private), and if his secret got out, he’d probably lose his crown to hungry neighbors and usurpers riding a wave of popular disgust.

- Hatshep (Vengeance, Two Years, Betrayal): up until two years ago, Hatshep was Abelard’s court wizard and advisor. When he finally granted her independence of action and sent her to conquer the territory to the northeast, she did just that – and declared independence. Since then the two have been at loggerheads, kept from outright war only by the looming presence of the Tilean princes.

Wizard-Empress Hatshep I (Wizard, Border Princes, Fourth Career, Give Me Liberty or Give Me a Moment to Run Away, Follow Your Instructions, Strange Hobby, Phobia, Six Courtiers): Hatshep is an enigma; she was born in Camet (in her current capital, in fact), but vanished before she hit 10 years old. Her parents believed she’d been killed in a raid. When she returned years later, not only was she alive, but she’d somehow gained the trappings and knowledge of a junior Celestial Wizard (even though she can’t bear the sight of anything painted in that order’s midnight blue). She tells no one how she gained her knowledge or why she returned, though she’s loud enough about her power that she seems unconcerned of rumors getting back to the Empire (her past is left to the GM). Whatever her past looks like, shortly after returning Hatshep took up employment under Abelard and served him loyally for years before getting ahead of herself and claiming a stretch of land near the place of birth as her own. She has since learned to regret her decision. She declared independence by accident (she claimed a village as her own instead of Abelard’s, which he couldn’t allow) and does not have the skill or experience necessary to stay afloat. If she can make it through the next few years she will harden into a proper Border Prince, but as of now she desperately wishes she were anywhere else. Hatshep may well be the only ruler in the Border Princes who wants to be deposed, just as long as she can survive the experience; she would be loyal (and a lot more careful) serving under anyone smart enough to peacefully replace her. That’s if they can figure that fact out, though. If her enemies were looking to undermine her more efficiently, they wouldn’t have to play mind games, just check her basement. Hatshep

And with that, we finally finished prince generation. Next up is actually looking at the territory they rule.

Inhabitants

Original SA post

Chapter 3: Inhabitants

After the Colossus that was chapter 2, chapters 3 and 4 are relatively short, so they should go a bit faster. As far as 3 goes, principality generation takes up maybe four-fifths of the chapter with the remainder being stuff for character creation.

It turns out I got the numbers wrong earlier in the review; instead of a village every square, you get maybe one village every four squares, and that’s in the most fertile regions. Most settlements end up under a prince’s control; they may be assholes, incompetent, or both, but they offer some military protection from the monsters and other princes that stalk the area, and that’s better than nothing. There are a few settlements that go it alone, but they are very much exceptions.

You generally encounter three kinds of settlement in the Border Princes; towns, villages, and homesteads. Towns are rare; you can have a max of one per principality and they never show up outside of one without some force keeping them independent. They are distinguished by, unlike every other kind of settlement, not devoting most of their population to agriculture in some way; towns are couple-thousand-people-strong trade and manufacturing centers (they get one distinguishing feature per thousand people), the only ones in the region. Villages, averaging at about 150 people, show up much more frequently; they pop up pretty much everywhere they can access enough farmland to support them. However, most of them don’t have distinguishing features so the book doesn’t advise generating them in detail. The same goes for homesteads; an order of magnitude smaller than villages, they show up a few times per square, but the bulk don’t have distinguishing features either.

What sets important settlements apart – and what makes them worth generating – are a variety of special features the book presents in one of its customary fat charts. During principality creation you roll up the number of towns, villages, and homesteads (the first two are functions of the principality’s size while the last is just a d10 roll) that have said features, then roll up what sets them apart, possibly moving on to other gigantic charts. These features come in several flavors; economic resources, strongholds and chokepoints, and special features.

Economic resources cover any kind of economic activity in general, whether resource harvesting, crafts, or trading. All settlements have some amount of all three; everyone can pull in agricultural products, make low-quality goods, and trade with visitors. What sets settlements with economic resources apart is their access to more or better stuff than everyone else.

- Raw Resource: the settlement specializes in extracting some kind of non-agricultural resource; these range from foraging or hunting operations to mines to quarries. A few of these settlements harvest gemstones or precious metals and get a free fortress to protect them.

- Craft: the community houses either several professional craftsmen or one expert; they can be anything from potters to smiths to brewers. Some of these communities have professionals that work with gems or gold; these also get a fortress gratis since they are big bullseyes to every raider in the area.

- Oddity: any resource (or unique feature) not covered anywhere else. Supernatural features show up elsewhere in the tables; these are things like ancient battlefields that you can find coins in if you dig in them or an actually, legitimately honest trader (both examples from the book). There’s a little table you can roll on if you can’t think one up.

- Market: trade centers. Not much more to say, other than these are good places to meet strangers and hire people. These can’t show up in homesteads, and if you manage to get two rolls for a settlement and both turn up markets, you should replace the second one with a Crafts result.

If you don’t pick up an economic resource, you get one of the other results on a table;

- Stronghold: any settlement with enough defenses to hold out for a month or more against a hostile force. Strongholds in the Border Princes are legit strong points; the book sets minimum requirements at stonewalls 12 feet high, ramparts, towers at the gates, and a source of fresh water. Since fortifications are so useful in a war-torn area like the Border Princes, most remain occupied long after whoever else them dies.

- Chokepoint: any place people have to go through to get from one area to another, whether a river crossing, mountain pass, or bridge. As such they need to be carefully placed during principality creation. Since they tend to see a steady flow of people, chokepoints make good places for adventures involving unknown and unpredictable people, and they also make good spots for climactic battles against enemy armies.

- Cultists: by a slim margin the most common result on the distinguishing features tables, rolling this means the community (or a subculture within the community) comment specifically houses some secret cult (open cults are covered elsewhere). Most often followers of Slaanesh and Tzeentch (the other two gods are a bit unstable for long-lasting communities), these settlements tend to be secretive and hostile to visitors; the book specifically recommends they be used for unexpected adventures that catch players off guard or introduce a new element in the campaign on the way to something else. They can also be groups of heretics or worship some other power.

- Special: any other distinguishing feature. These range from religious communities to local spell casters to monsters that frequently interact with the settlement (and a sufficiently “friendly” monster might be enough to support a town outside of a principality). You also have a one in five chance of rolling for two distinguishing features.

A few careers.

Once you’ve rolled all these out (and decided their names, there are several charts in an appendix for randomly rolling up place names of various types), you’re done building a principality. The next section covers character creation for the Border Princes, but for the most part it’s just a list of careers for players to choose. Not too much exciting here; there are special careers for swamp dwellers, long-distance traders, various flavors of religious weirdos, and so forth. It’s much shorter than the last section, and once you’ve read it, you’ve finished the chapter.

I’ve gone ahead and rolled up Camet’s principalities, but I’ll try and keep this update short and sweet. I’ll go over some of the highlights in the next update.