The Challenge of the Bandeirantes by Cyphoderus

Adventures in the Land of Santa Cruz

Original SA post

The Challenge of the Bandeirantes: Adventures in the Land of Santa Cruz

O Desafio dos Bandeirantes (The Challenge of the Bandeirantes) is a Brazilian pen-and-paper RPG. Published in 1992, its biggest claim to fame was being the very first RPG presenting a fantasy based completely and unashamedly on Brazilian history, folklore, and culture. It wasn't very successful in its time, because you know how nerds are: people were still mostly interested in playing Germanic Übermenschen slaying kobolds in medieval castles. The average Brazilian has a very low self-esteem regarding their own country, and a habit of not believing something made in Brazil is better than a foreign version (this right here is why football is such a big deal). In 1996, the publisher closed its doors.

Desafio dos Bandeirantes, however, was game-changing. Today it is spoken of as an anthological chapter in the history of Brazilian RPGs, which is longer and more elaborate than you'd think – a few years ago, I read that Brazil has the second largest RPG-playing population, behind only the United States itself. Anyway, back around 2000 or so, we had our own Satanic RPG scare, after a homicide (in São Paulo, if I recall correctly) was associated with people who played Vampire. The scare never got too big, because for every group of misguided goth teens with a copy of the Book of Nod there was a teacher in a school somewhere using either Desafio dos Bandeirantes (or the licensed national line GURPS Discovery of Brazil ) to teach children about history and culture.

Desafio dos Bandeirantes is very much a child of its time, with sprawling tables and naturalistic monster lists and all that you'd expect from a 1992 RPG. Its biggest flaws are a GURPS-like realistic system and a setting that is held back by trying to be too verisimilitudinous where it should not be. These are problems because the game's entire premise is one of fantastical adventure. There is, thankfully, no metaplot involved.

Desafio dos Bandeirantes presents a setting of colonial Brazil circa 1650, where magic is real, the gods are real (all of them), and the virgin tropical woods are inhabited by all kinds of creatures from the national foklore. By the end of this writeup, you too will be able to differentiate between the boitatá, the saci-pererê and the curupira. One of them is a one-legged prankster entity with a red cap and a pipe, one is a giant snake made of fire, one is a devilish protector of the forest with backwards feet. Try to guess which is which!

I'm doing this because this setting is a hell of a whole lot different than anything else out there. It is familiar to me in the sense that maybe a wild west setting is familiar to someone born and raised in the USA, but a lot of things here should be new and interesting. I'm of the opinion that we should always be on the lookout for new kinds of inspiration for our tabletop games.

This writeup will be of the core book. There are a couple of adventures and one or two setting supplements, but I don't have those and I bet they are freakishly hard to find nowadays.

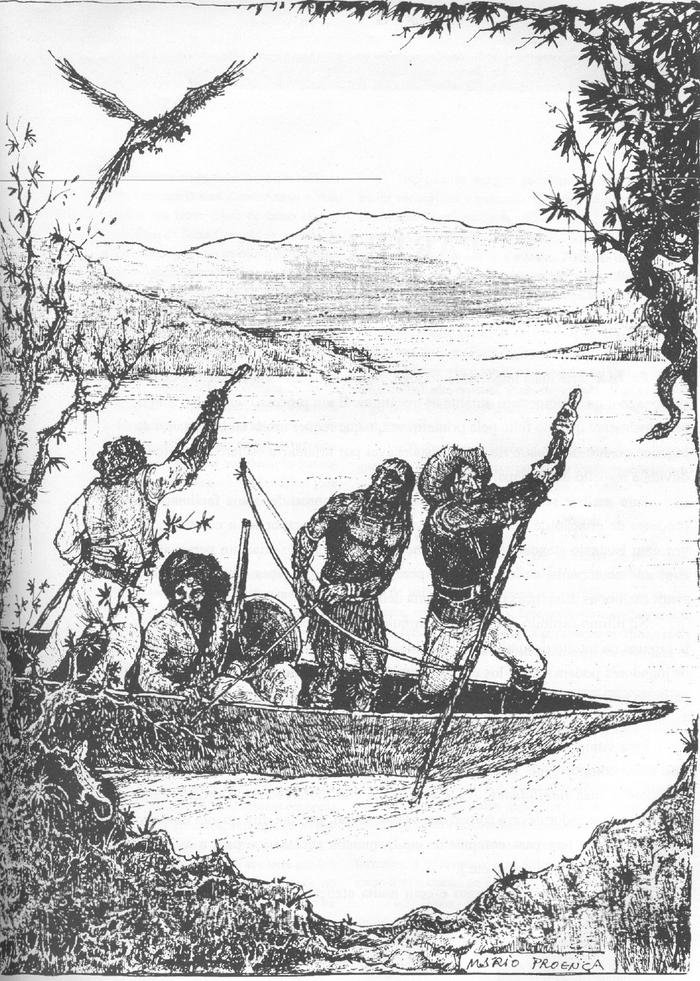

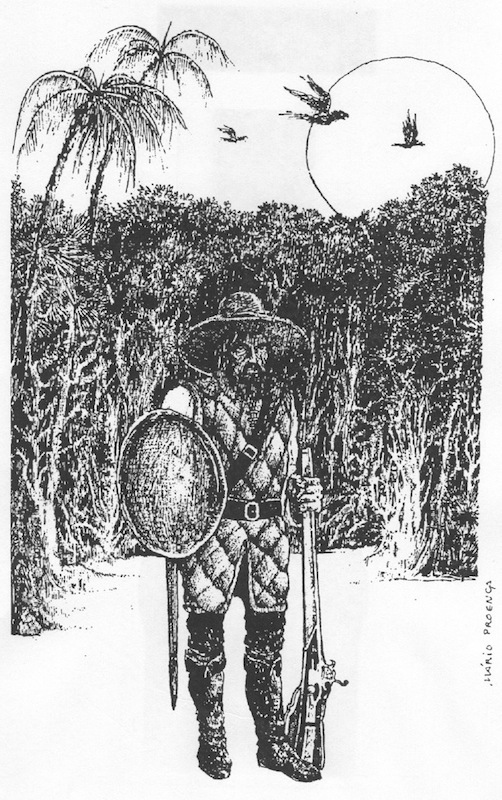

Culture corner: the bandeiras. The European settlements were located along the coastline in colonial Brazil. The bandeiras (flags) were the expeditions the settlers made inland. They were mostly for finding ore (silver, and later on, gold) or for dealing with the native indian tribes: trading, converting to Catholicism, or capturing as slaves. The people who undertook these expeditions were called bandeirantes (flaggers) , and give the game its name. The bandeirantes were extremely important for Brazil, historically, because they settled remote inland locales (ever wondered why Brazil is so big compared to the other South American countries?) and named most of them, which is why Brazilian places can have the weirdest names like Itacoatiara and Aiuruoca. These names are ancient and in the lingua franca of the time: the native tupi-guarani language of the indians. We'll talk more about it in another culture corner down the road, probably.

Introduction

Original SA post

The Challenge of the Bandeirantes

Part 1 - Introduction

Challenge of the Bandeirantes opens with "you probably walked into a bookstore and the cover or title of this book called your attention. Maybe you've heard about it from someone and decided to go see what it's all about. Maybe you just got it as a gift and have absolutely no idea what to make of it." The book then introduces itself to you: it is a role-playing game, and with it you and your friends can have hours of fun pretending to be cool people in a fantastical version of colonial Brazil. Please, don't stop reading, we guarantee that it's fun and exciting.

This makes Challenge probably the first RPG book that I've read that admits it must look utterly bizarre and unaproachable to someone who uncaustiously opens it. It goes to the trouble of calming the random reader by explaining itself very clearly in very big letters. I like it.

As every RPG book aimed at beginners, our first chapter (after the introduction presented above) is one about the nature of RPGs. It has the standard paragraphs: what are RPGs, what you need to play, how to read dice ( Challenge uses a percentile dice system), etc. Of note here is our first little blurb about the setting itself.

The first thing you notice is that Challenge is not merely a Brazilian reskin of D&D. It isn't even very high-fantasy, for the most part.

The game is set in the Land of Santa Cruz (Holy Cross) , in 1650 of our own calendar, in a world much like ours at the time. This is in fact the first difference between our world and the game's: Brazil was indeed called the Land of Santa Cruz for the first few decades after its "discovery", in 1500. The name was quickly changed to Brasil because of the vast amounts of pau-brasil found, an extremely valuable tree that could produce blood red tincture. Red was for many centuries the most valuable tincture, which is why kings' mantles were all red. Pau-brasil was the chief export of Brazil for a long while and gives the country its name. In the game, the name Land of Santa Cruz was kept until 1650.

Another important distinction between the game's setting and the real world is that, in the game, there's been a treaty between the Portuguese Church and the Catholic Church which forbids the enslavement of indigenous tribes. Historically, many expeditions in Brazil (the bandeiras from last update) were undertaken with the purpose of capturing natives as slaves. In the game, this practice is forbidden, even though there are clandestine native slaves. Instead, the player characters will undertake expeditions to escort caravans between towns, deal with hostile tribes, find precious metal, and overall be more heroic than if they were slave-catchers.

Note: as I am not aware of the proper conventions of talking about natives in English, and as the average inhabitant of the United States thinks of "America" as their own country instead of the countinent, to refer to the native Americans showing up in the game I will use the Portuguese term: "índio". This term never became an issue, as the word used to refer to someone from India is different ("indiano").

Just like 1650's Brazil, the Land of Santa Cruz is in the middle of the process of colonisation. There are big settlements where the Europeans have stablished a very firm hold, and there are many places left completely unexplored and wild. Some índio tribes actively trade with the whites, some are openly hostile, some are neutral, and some are so isolated they aren't even aware of the whites' presence. The black are brought with the white as slaves, but, in the game, the proportion of black people who freed themselves is much, much higher than in real life.

The Land of Santa Cruz is magical. Player characters can harness the power of spells, spirits, gods, the Christian god, and more. Each culture has their own relationship with the supernatural: índios, whites, and blacks all have their specific ways of dealing with magic and religion. We'll talk more about this next update, when we talk about character creation. The Land of Santa Cruz is also inhabited by all sorts of creatures: all superstitions, urban legends and myths from back then or from today relating to back then are considered real. The wilderness is teeming with supernatural creatures, and most are hostile.

And, finally, the names of the peoples are changed. There are no Portuguese in the Land of Santa Cruz, but lusitanes (Lusitânia is an archaic name for Portugal). There are no Spanish, but castelanes. The same thing happens with the índio tribes who appear in the game: the tupi are represented by the jaguaris, the guaranis by the maoáris, and so on. This, the game explicitly tells us, is so that the players can feel more at home in a fantasy setting and cast aside their natural preconceptions about these real world people.

In other words, the setting of Challenge of the Bandeirantes isn't as much fantastical as it is historical. It's a version of historical Brazil were myths and folklore is truth, and many design decisions are made throughout the game to keep verisimilitude with the real world. I believe this is a point in the game's favour. One of the game's design goals is to get people away from imported D&D fantasy and into a very national kind of imagination space; the extra grounding in reality helps with that. And the part that's not grounded in reality – the fighters and casters and creatures and less goddamn slavery – all help create a setting where adventure is possible and encouraged and everyone can have a good heroic time.

Next time: character creation! Four kinds of wizards, three kinds of priests, and the poor fighter is still the poor fighter

Please let me know if something is poorly explained. I might left something important out because I don't know what things from 1600's history you guys are familiar with.

A Brief Interlude About Colonial Brazil

Original SA post

Since you guys showed interest, I tried my hand at putting together a brief primer on the state of affairs in colonial Brazil. This is pure history, no game, so feel free to skip it. Next update we'll resume talking about classes and attributes and stuff. I would say it's kinda required to understanding the aesthetic and themes Challenge of the Bandeirantes is aiming for, though.

I actually feel that my English is not quite good enough to talk about this stuff as I would like to. Please tell me if anything's unclear or if you're interested in a specific part of the history.

Challenge of the Bandeirantes

Bonus Update: A Brief Interlude About Colonial Brazil

Brazil's colonial period goes from 1500, when it was first "discovered" by the Porguguese Pedro Álvares Cabral, to its independence in 1828.

The important thing to know about colonies is what they are. A colony isn't a land of promises, it isn't a land of new beginnings. A colony is a natural resource. A colony is what happens when a country sets foot somewhere new and goes "no one was here before, and since this is outside of Europe (where borders matter, duh), I thus declare it as belonging to me." A colony is treated no different than, say, a gold mine found inside the country: it is the country's property, and the country has the right to extract the resources from it for themselves.

That's what Brazil was: a place where Portugal could go to extract resources for itself. What these resources were varied with time. It started with the extraction of pau-brasil, a tree that could produce red tincture, a very valued commodity in the 1500's. From circa 1600 on, pau-brasil is mostly drained out, and the main export of Brazil starts being sugar, produced in huge sugar cane plantations and processing farms. In circa 1700, gold rises in popularity throughout Europe and a lot of it is found in the mines of Brazil, so that starts being taken rapidly. From circa 1800 on, we start seeing huge coffee plantations, and that becomes the main export.

Of course, mostly no care at all is given to the colony's well-being and natural integrity; again, a colony is a resource, there to be explored. Pau-brasil was never planted, but taken directly from the (at the time) huge and apparently endless forests of the coastline. To have sugar cane and coffee plantations, you have to clear the forest. And so on. It works like this: the Crown gives you a concession of something. So you're a big merchant, or a noble, or someone important, and the Crown (who owns the colony) gives you rights to the pau-brasil in a determinate area, or to stablish your plantation of so-and-so size, or to sell whatever goes through so-and-so port, etc.

And that's the kind of person who comes to a colony. Not hopeful people looking for a new beginning – well, that too, but they're a vast minority. Who comes to a colony are merchants, traders, and other people who want to benefit and take advantage of the colony in some way. The European "settlers" are the 16th-century equivalent of enterpreneurs. Many even have to go involuntarily, the 16th-century equivalent of being relocated to India because your software company's base is there. Most don't bring families.

Now a little about the natives. The word to remember here is "variety". Today, wikipedia tells me Brazil is home to over 300 different native ethnicities, who speak over 270 languages. That is

today

. At around 1500-1600 that number was... significantly higher. Indians have occupied the country's region for millenia, and they diverged into hundreds and hundreds of distinct cultures and ethnicities. There is no "native Brazilian culture", there are hundreds. Which means that during colonial times, each tribe had their own opinion and attitude toward the settlers. Some tribes were openly hostile. Some were neutral. Some were amicable, and traded with the Europeans.

Let's go back to the European mentality here for a second. A colony isn't a "promised land". The presence of the natives isn't a wrong that must be righted. As everything else in the colony, the Indians are a resource to be explored. Yes, there was open slaughter of natives, but mostly if they were hostile. If a tribe could be traded with for profit, then it was. If a tribe was too peaceful, then it got taken as slaves. Of course with the constant expansion of European occupations and plantations, many tribes were found to be "in the way", or they succumbed to disease, or their habitat got completely destroyed.

Here's an image of a pau-brasil to break up the wall of text a little. The Atlantic forest used to have entire kilometers filled with these.

Nowadays, they're rare, and symbolic. Kinda like what the bald eagle is to the USA.

In contrast to the more famous native American tribes (the incas, the mayans, the aztecs...), the Brazilian natives were much less technologically advanced. Many tribes were semi-nomadic, and most were hunterer-gatherers. A lot of them actively practiced agriculture, and we owe to them, for instance, the domestication of the cassava. Aesthetically, they were also very different from the native Americans you are used to seeing in the media (try image-searching the term "indígenas brasileiros" for a glimpse). Another thing is that the Indian tribes had a very complex political structure among themselves; some tribes hated other tribes which were allied to other tribes. Unfortunately, we know extremely little about "internal native politics".

What about the Africans? Well, with the rise of sugar cane processing farms, and later on, coffee farms, the influx of African slaves to Brazil was huge. They came from many different African nations, each with their own distinct ethnicity and culture. There were also many escaped slaves, and they formed hidden communities in the depths of the forests (called "quilombos"). There were also freed slaves, and their numbers would rapidly increase until the lei áurea

(golden law)

of 1888, which freed all slaves.

The main point I want to make with this post is the following: colonial society is not the whites vs. the world. It is a crazy mix of everything above. Cities are bustling with whites, Indians, and blacks. You can find whites and blacks in Indian tribes, talking leisurely. Children born of different ethnicities became common and, after a while, the norm. It was not social equality by any means (blacks are considered subhuman, natives are only tolerated insofar as they're useful or too much trouble to deal with), but happened in Brazil was

cultural

mixture. Throughout the colonial period, white, black and native culture got together and had a child that we call "Brasil". A lot of our folklore is native in origin, as well as the habit of taking baths every day (something the Europeans didn't share and... may still not share); a lot of our religion is influenced by African religion... and so on and so forth.

What about the lay of the land? Well, Brazil is huge. To the south, there's temperate climate and forests of pines. Along the shoreline, there's the Atlantic rainforest; it was a very huge tropical rainforest, like the Amazon but even more incredible and with even more biodiversity. Of course, it being along the shoreline, barely exists nowadays and has been devastated since forever for pau-brasil and clearing land for plantations and etc. To the northwest, there's the Amazon rainforest you're aware of. In the center of the country, the space is more open and the vegetation gets sparser and lower. Think of it as savannah-like; we call it "cerrado". To the northeast, the climate gets arid and very, very dry; the land gets desert-like. We call that one "caatinga". There were Indian tribes populating all of these distinct areas, by the way. Another testament to their variety.

And this is where Challenge of the Bandeirantes dumps us. Smack dab in the middle of the colonial period, in 1650. For 150 years, the colonisation has been a reality. The European settlements and plantations are well-stablished; the Indian tribes each have a formed opinion of the settlers; the African have also firmly stablished a foothold in society. However, the settlers haven't ventured too far yet: there are still

vast

amounts of completely unexplored land.

This gives us a setting that has a lot to do with D&D's Points of Light: there are cities, and friendly Indian tribes, and remote villages and settlements with few people. But, between them, outside the travelled roads, anything goes. Dangerous creatures, people and places lurk in the unexplored forests. The ones brave enough to confront them will find riches, beauty and fame unimaginable. And, like all PC parties, this is where we come in.

Tune in next time for character creation!

Culture corner: the end of the colonial period.

After the French Revolution, Napoleon came into power. The Portuguese king at them time, Dom João VI, chose to run the fuck away from Europe instead of confronting the French and their increasing might. He chose to come to Brazil, Portugal's most prosperous colony. This was in 1808. The capital of the Portuguese kingdom was temporarily transferred to Rio de Janeiro to reflect this. Suddenly, Brazil was super important. It was were the Kingdom of Portugal was located! All the nobles came, the entire royal family came, anyone who was anyone came.

What happened was that the king noticed how unstable the colony was. Things were moving too fast here for him to control, and he realised that if he didn't do something the colony would rebel and be lost. So he had his son declare Brazil's independence. This happened in 1828. Brazil became an empire, with the prince of Portugal becoming then the first emperor of Brazil, Pedro I. He was still the prince, and in 1831 decided to return to Portugal to deal with Portuguese problems and become the, you know, Portuguese king. His son, Pedro II, was left as the Brazilian emperor. No, it doesn't matter that he was 5 freaking years old at them time.

Actually, Pedro II would go through substantially less batshit crazy stuff than the rulers of Europe did at the time, and rule for over 58 years as a decent, well-liked emperor. I guess being away from the incest and conspiracies of Europe does that for you. Pedro II left the thron in 1889, then Brazil became a republic.

Races

Original SA post

Challenge of the Bandeirantes

Part II - Races

The book opens with character creation. A character in Challenge of the Bandeirantes is composed of the very familiar elements race, profession, attributes and skills. Profession is what we're accostumed to call "class" in other games: it's the niche played by the character in the adventuring party. Lastly, we have social class , which is randomly rolled. It represents the character's standing in colonial society, as well as their funds available for purchasing equipment at the start of the game.

In a very traditional layout, we've got one chapter for each of these elements waiting for us.

Character Race

Challenge of the Bandeirantes avoids that pesky problem of RPG races being thinly-veiled allegories of real-world races and cultures by skipping the allegory step altogether. The available player character races are straight-up real-world ethnic groups.

Race is pretty big decision, the most important one you'll take in character creation. Challenge of the Bandeirantes is not a game of equal opportunity; race determines what professions and social classes are available to the character, and locks them out of the rest. You could argue that a game about fantastical adventure should have mold-breaking characters, and that verisimilitude shouldn't hold great ideas back. As much as it would be cool in a 1650 setting to have a rich black person or a white man initiated into the índios' magic, Challenge of the Bandeirantes doesn't allow it. At least not out of character creation.

Here's what the game has to say about it:

quote:

It's important that the player keep mind that these races are described as they appeared in the XVII century. The black were enslaved until the end of the XIX century; the natives were exploited and lost much of their culture; and the white felt themselves superior and owners of the truth. All this is part of our History, and to despise any of these facts would be to miss the point of this RPG, which is, basically, an entirely national setting. There are, of course, some adaptations made for the rules of the game, and to make it more pleasant.

Let's get to our options.

White

The white man comes to the Land of Santa Cruz for the most varied of reasons. Some want to get rich by exploiting the land through planting and slaves, some by trading new products or finding new consumer markets. Some come for the thrill of adventure in a new land, some come because they're running away from the metropolis, and some even come to honestly stablish for themselves a new life.

Social class: the white can be of any social class, except slave. It means they can be filthy rich and exceedingly important to the metropolis, or poor dudes who own nothing but the clothes on their back. The book does not discard the possibility of a white slave, but mentions that it'd be a pretty huge deal and should be treated as an influential plot point.

Professions:

Fighter. The classical RPG fighting man, versed in the use of weapons and standing strong at the party's front line of defence.

Tracker. The RPG "ranger", the tracker is the guide, pathfinder, and survivalist of the group. When most of the land is unexplored and wild, the tracker is a valuable member of the party.

Thief. Another one we're used to, the thief is the adventurer specialised in "creative problem-solving".

Jesuit. The Company of Jesus were a Catholic order specialising in "missions", excursions into new, unexplored lands to bring the word of Jesus to the natives. The jesuits were very present and a key factor in the colonisation of Brazil. Think of them as adventuring priests.

Witch (the internet tells me the term can be used for both males and females). A practitioner of the old European witchcraft arts. The Church is absolutely not happy about them, and some of them end up in the New World.

Índio (Indian)

The índio in the Land of Santa Cruz has the home advantage. Despite having way less technology than the white, the índios make up for it by knowing the land's history, its legends and its nature.

Tribe: There are many different índio tribes, and we'll talk about a lot of them a few chapters down the road. The game offers 8 options of tribes for a newly created character. They have no mechanical impact, but are a pretty big deal because tribe determines what's the relationship between the índio and the settlers.

Social classes: The índio can be a farmer, an artisan, free man, or slave.

Professions:

Fighter, tracker, or

Pajé. The spiritual leader of the índio communities, the pajé calls forth the magic of the land. Think of it as a shaman and you're not too far off.

Black

Blacks have a tough time in colonial society. In Challenge of the Bandeirantes, the possibility of a black person being free from slavery is much greater than it actually was back then. Still, the black is either victim of a lot of prejudice or runs away to join secret hidden black communities called quilombos.

Social classes: The black has the same options as the índio, though with more probability of getting the worse results.

Professions:

Figher, thief, or

Black priest. Calls forth the gods of black religion, being able to summon magic by incorporating them into his or her own body.

Black sorcerer. A practitioner of the magical arts of the black culture; a lot of it is about dealing with spirits.

Sorcerer of iron and flame. Can call forth the magic of these two primordial elements; the warrior-mages of black culture.

Mulato (brown)

The child of white and black parents is called a mulato. They have trouble fitting in with either of these cultures. The whites consider them too black and not seldom enslave the mulatos; the blacks consider them too white and often see them with the hateful, distrustful eyes they have for the white.

Social classes: The mulato has more possibilites of social ascension than the black, but still way less than the white. They can be small merchants, farmers, artisans, free men, or slaves.

Professions:

The mulato shares the black profession list: fighter, thief, black priest, black sorcerer, or sorcerer of iron and flame.

Mestiço (mixed)

This is the term the game uses for a child of white and índio parents, even though the proper term is the less generic "caboclo". Differently from the mulatos, the mestiços are seen as a boon by the European settlers, for they are valuable as bridges between the white and índios. For this reason, they are employed in negotiations and often ordained as Catholic priests.

Social classes: Same as the mulato: small merchant, farmer, artisan, free man, or slave.

Professions:

To quote the book: "the mestiço can be a figher, thief, or, in a very special case, witch."

The white feel superior to the others. The black, even the free ones, suffer from the slavery stigma and impossibility of social ascension. The índios are seen with prejudice, but are valued as strategic pieces in the colonisation or as respectable enemies. They can treat the white with friendship, mistrust, or hostility.

The mulatos and mestiços can lean more to one of their cultural sides or other. They can be accepted in colonial society or choose to embrace their black or índio ancestry.

Culture corner: miscigenation. It's worth remembering that Brazil, and by proxy, the Land of Santa Cruz, is an extremely miscigenated country. It ties with the fact that many settlers did not bring their families. Miscigenation became common, then it became the norm, and nowadays there is in practice only one huge, mixed Brazilian lineage. The whitest of Brazilians can very well share as much African ancestry as the blackest of Brazilians. Mixed physical features are the norm.

This means picking a white character at character creation very likely means someone who just arrived from Europe. Someone born in the Land of Santa Cruz is very likely a mulato or a mestiço.

One thing that's sorely lacking from Challenge of the Bandeirantes is a black/índio lineage. These people were called "cafuzos" and they weren't by any means uncommon. One of the game's biggest flaws is lack of material on the relationship between índio and black culture. It is also the hardest kind of thing to gather information about in real-world history, but that still doesn't forgive the lack of a cafuzo character race.

Because of the miscigenation thing mentioned above, the terms caboclo, mestiço, and cafuzo are obsolete nowadays. Mulato is still used, but to denote a brown skin color, not white/black parents.

Next time: the professions!

Bonus culture corner: let's pronounce!

Santa Cruz - (SAN-tah CROOZ)

índio - (EEN-dee-o) The í is an i with an acute accent, with makes strong the syllable where it's at, like this:

pajé - (pah-JEH)

mulato - (moo-LAH-t'o)

mestiço - (mes-TEE-s'o) ç is a c with a thingie and it sounds like "ss".

caboclo - (kah-BO-kl'o)

cafuzo - (kaf-FOO-z'o)

All the 'o are meant to indicate a short "o" sound, not the crazy long "o" of the English language.

I Swear This Isn't AD&D

Original SA post

The Challenge of the Bandeirantes

Part III - I Swear This Isn't AD&D

To meaningfully explain what each profession is capable of, we need to talk about skills, and to do that we need to talk about attributes. This update isn't very exciting, but it's also not very long. Let's get to it so we can move on to better stuff.

Characters in Challenge of the Bandeirantes possess seven distinct attributes. They are as follows:

Strength: Is strength. Gives bonuses to melee weapon and unarmed combat damage. In the grand tradition of every RPG ever, we have a big table of carrying and raising capacity for different strength values.

Dexterity: Is dexterity. In the grand tradition of every RPG ever (this is a theme), it governs a bunch of skills and is thus very important for any character.

Resistance: Is straight-up hit points. Taking damage reduces resistance directly. Resistance can go down up to -8, when the character dies. Between 0 and -7 resistance, the character's wounds get progressively worse, in the (repeat with me, kids) grand tradition of every RPG ever.

Resting for 6 hours recovers 3 points of resistance. No die rolls or anything here, 6 hours = 3 resistance for all characters.

Intelligence: Not much to say here. Important for sorcerers.

Wisdom: ...yeah. Important for priests and for the tracker, as wisdom, in the grand tradition of

Charisma: I really don't know what to say.

Luck: Hey, something new! There's a separate luck attribute. It gets rolled for random events, like gambling and who gets caught in that accidental blackpowder blast.

Determining attributes is easy. Every attribute starts at 10, except for luck, which starts at 0. Race and profession give bonuses:

White: +1 dexterity, +1 resistance

Índio: +1 dexterity, +1 wisdom

Mestiço: (recall, white/índio children) +1 dexterity, +1 resistance

Black: +1 strength, +1 resistance

Mulato: (recall, black/white children) +1 strength, +1 dexterity

Fighter: +1 strength and resistance, -1 intelligence and wisdom

Tracker: +1 dexterity and wisdom, -1 strength and intelligence

Thief: +1 dexterity, -1 strength

All sorcerers: +2 intelligence, -2 strength

All priests: +2 wisdom, -2 strength

As you can see, attribute bonuses and penalties are not equally distributed among races and professions: nothing gives charisma or luck bonuses, and all professions except the fighter get a penalty to strength. Attribute bonuses based on real-world ethnicities is still the worst idea of all time, but you'll notice that all races have the same base intelligence and charisma, and the game goes out of its way to explain that índios get +1 to wisdom to represent their better knowledge of the land. It's not so bad.

Lastly, the player rolls 7d6. They then assign one die to each attribute as a bonus. If you roll 3, 3, 4, 1, 1, 2 and 4, for instance, you get +1 to two attributes, +3 to two of them, etc. At this point, feel free to increase luck.

Also remember that this is 1992, before the era of ability scores and ability modifiers. Instead, attribute tests are made in the true classical way: roll 1d20, if you get under the attribute, it's a success. Attribute tests are for when no specific skill applies to a task. The classic examples are forcing open a door (strength) or catching something mid-fall (dexterity).

Luck is a 1d10 roll. It's good, because no one's luck is above 6 – the only way to get it is through the bonus dice roll. You do luck tests when you want to avoid a random accident, remember to have packed something, win at a non-rigged card game (as if such a thing would exist in an adventurous world) and the like.

Skills

With attributes under our belt, we can talk about skills. Challenge of the Bandeirantes is one of those games with a huge list of skills, some with very dubious use, some obviously more useful than others, and some that seem to be added solely for verisimilitude reasons: there's a "dealing with cattle" skill that explicitly mentions it shouldn't be rolled in everyday situations. It might not be a good idea to invest in it unless your game somehow features a lot of stampeding cows, or if you want to be a realistic cowboy (but who does that?).

Anyway, skills work in a percentile system. Your value in a skill is the % chance you have at succeeding in an average task pertaining to that skill.

Skills are bought with points. Each character starts with 170 points to distribute among their skills. Of these points,

100 go into career skills, the "class skill list" of the character's profession;

50 go into general skills: these can be career skills of other professions (magic excluded) or chosen from a list of generic, profession-less skills;

20 go into the dodge skill. Don't argue.

You can never put more than 20 points in a skill. The final skill value is governing attribute + points spent. Thus, every character starts with dexterity + 20 dodge.

Skill tests are, predictably, done with 1d100 roll-under. Some skills you can't use at all if you haven't got points in them, like managing explosives and swimming (17th-century swimming is hard, guys). Some skills can be used untrained with just the governing attribute value; some can be used untrained, but only at half of the governing attribute value. There's some weird choices here, like "fighting with sword/knife" being in the latter category, making your average sorcerer capable of stabbing someone 5% of the time. Or the "dodge" skill being labeled as something that you can use untrained even though putting points in it is mandatory for every character. Game design!

This has been a mostly boring update, but next time we'll launch into the profession descriptions properly. Spells are for the most part treated as separate skills.

One thing I find interesting about Challenge of the Bandeirantes is how it employs a brander form of random attribute rolling: ~10 + 1d6 is much less horrible than 3d6. I'm impressed we don't see this kind of thing more often.

Next update: In this game, a fighter has the career skills to fire cannons.

Profession: smashing dudes

Original SA post

Challenge of the Bandeirantes

Part IVa - Profession: smashing dudes

Recall that what Challenge of the Bandeirantes calls a "profession" is what we'd call a "class" in any other game. It's the character's role and niche in the adventuring party, what determines their heroic skills, not what they do for a living. What they do for a living is, curiously enough, called a "social class". Terminology!

Today we'll take a look at the mundane, non-caster classes. These are the fighter, the tracker, and the thief. Challenge of the Bandeirantes features no equivalents to feats, class features, or anything of the sort: the only feature granted to a profession is its list of career skills.

The fighter

The fighter is the only profession available to all races, as "warrior" really is an occupation that defies culture and technology.

The fighter is the local master of warfare. As in, all sorts of warfare. Challenge of the Bandeirantes has no concept of common or exotic weapons – as such, if there's something around that can be used in a fight, the fighter has got a skill and can learn to use it. Too many games put too much limitation on their warriors: you have to be a "gladiator" to use a net in battle, or an "engineer" to know how to fire a gun. To the fighter in the Land of Santa Cruz, however, there are no such limits. Survival depends on versatility, and for a combatant, versatility means having no qualms about using "unusual" weapons.

Here is the fighter's skill list:

Dodge and perception: Every profession has these as career skills. They do what you expect them to. Dodge is the primary means of defending from attacks; we'll learn more details when we get to combat.

Fight with weapon: Every different category of weapon gets a distinct skill. I will mention these because, again, Challenge of the Bandeirantes has no concept of "exotic weapons", so the available list is more interesting than your run-of-the-mill Medieval Simulator™ RPG.

Fight with sword/machete and fight with axe: the boring options.

Fight with bow and arrow: extensively used by the índios for hunting.

Fight with whip: a whip is great. It can be used for handling cattle, as a rope, to disarm and to fight with. It has suffered in other games by being made hard to use. In the Land of Santa Cruz, a whip is a surprisingly common utensil and thus a perfectly reasonable choice of weapon.

Fight with dagger/knife: includes knowing how to throw them.

Fight with spear/javelin: both of these are also traditional índio weapons. The spear is used more for single combat and rituals, while the javelin is commonly used for hunting.

Fight with pistols: lightweight firearms, the pistols carry only one shot and require reloading.

Fight with musket/blunderbuss: longer, more powerful firearms than the pistols. The musket is used for precise shots, the blunderbuss shoots spreading fire like a shotgun. They also require reloading after one shot.

Fight with cudgel/tacape: a tacape is a club. It is a traditional weapons of the índios. These aren't caveman clubs, however: much as the Irish have their special shillelaghs, the índios have their tacapes. The typical índio tacape has an elaborate design, suited for either ritual, cultural purposes or to better bash people's heads in. Designs vary greatly from tribe to tribe and weapon to weapon.

Fight with net: used offensively, the net is a great tool for hindering the opponent's movements. Mechanically, it increases the difficulty of every action the opponent takes when under the net. This means every skill is used at half value: a very viable tactic in a percentile-based system.

Fight with zarabatana: it's a blowgun, but I just find the word "zarabatana" irresistible. Another typical índio weapon that fires darts. The darts themselves do no damage, but in a tropical land with a dazzling biodiversity of flora and fauna there's a lot of things you can coat those darts in. There are seven different poisons and venoms available, including curare

Fight with 2 weapons: When you're wielding two weapons, the off-hand weapon attacks at a penalty, but if you roll this skill and succeed, you can use it at no penalty at all. The game goes to the pain of saying that, for left-handed people, the right hand is considered the off-hand one. Thanks, game!

Fight unarmed: The signature fighting style of the black. Being social pariahs, empoverished, enslaved, or usually all of those, the black had little access to weapons. Nevertheless, not a small number of them came from straight-up African warrior cultures and were very, very good at fighting. When they came to Brazil, these warriors from wildly different cultures were forced to live together for the first time in the same society. What happened was a huge interchange of fighting styles. The "mixed martial arts" that emerged then was called "capoeira". It would give the black and the poor an edge in hand-to-hand confrontations for centuries, and its better practitioners would go on to become legendary, almost mythical.

Handle big guns: Is the skill used to fire cannons and other forms of heavyweight artillery of the time. I told you the fighter was versatile.

Handle explosives: This skill is required for using handle big guns , and represents the character's familiarity with gunpowder. It's not necessary for use of pistols, muskets, or blunderbusses, however. Failure on a roll means the stuff fails to explode at all, or worse, it explodes at the worst possible moment. This would be a great time for a luck check.

Ride animals: The standard riding skill, used to control your mount when the going gets rough. The skill description uses the ambiguous term "mount" insted of "horse", so there are a lot of mythical creatures and exotic animals just waiting to be mounted, if your game goes for a more fantastical quality.

Repair weapon: Requires a specialty, like "repair pistol" or "repair whip". Not much to say here.

Repair leather armour: The only kind of armour available in the Land of Santa Cruz is leather armour. Armour in this game degrades as it takes damage. With this skill, the character can patch up their protective gear to recover some of its lost resistance, provided they have the materials around. It shouldn't be hard to find leather in colonial society, though. Each piece of armour can be repaired up to three times.

And that's the fighter's skill list. The fighter can learn every single one of the game's fight with... skills: there aren't any weapons available besides the ones listed here. There's one interesting thing, however: as much as the game restricts profession choice by race, there are no restrictions on who can learn what weapon skill – again, this is a land of cultural interchange, even if it's sometimes forced by circumstance, and warriors cannot afford to be picky about what they fight with. This opens many interesting possibilities for cross-culture characters: a black man using the zarabatana and javelin of índio culture, an índio who learned to fire a musket, etc.

Other professions have almost no weapon skills as career skills. This means that if non-fighter characters want to be good with a weapon, they probably have to use some of their 50 generic skill points to dip into the fighter's career skill list and pick something up.

I was going to do the write-up for the tracker and thief in this update, but it's gotten too long already. I am mixing the chapters up a little bit: I'll use the profession write-ups to cover the skills and spells chapters as well.

Next time: the 1650's ranger, or maybe we can do a caster profession to mix things up.

The Sorcerer of Iron and Flame

Original SA post Sorry for the delay and the shortness, but it's been a harsh week.

Challenge of the Bandeirantes

Part IVb - The Sorcerer of Iron and Flame

Magic

Magic works just like the characters' regular skills. Each spell is skill you must invest points in. Casting a spell requires a successfull roll of the spell – for all sorcerers, all spells are Int-based. Each caster profession has a spell list instead of a career skill list, and spells can't be acquired by generic skill points. A fighter, thief, or tracker cannot use their 50 generic points to learn a little bit of magic, and a caster can't learn spells from another caster's list.

The Sorcerer of Iron and Flame

I've mentioned that no small number of black people who were brought from Africa stemmed from warrior cultures. No where is this more apparent than in the sorcerer of iron and flame. Unashamedly offensive casters, these sorcerers are adept at manipulating (guess what) both iron and flame.

Only the black and the mulatos (black/white offspring) can become sorcerers of iron and flame.

The firey side of the sorcerer's spell list has some predictable entries: they can set fire to flammable things, throw fireballs, raise barriers of flame, and shoot cones of fire from their hands. They can manipulate an already existing fire source – for instance, to frighten villagers by making their village bonfire take the form of a giant firey bat. There's spells to extinsguish fire and make oneself immune to flame as well.

One interesting spell if flame of truth ; the sorcerer produces a fire that will burn only those who lie. You put your hand in the fire and nothing happens, but if you say something that's not true, you get burnt. Black society in the Land of Santa Cruz had one hell of an impartial judgment system.

The iron side of the sorcerer's spell list is less blatantly offensive. The sorcerer can read the recent memories of one metallic object. They can coat his own skin in iron, forming a protective carapace, or mold iron like clay. They can locate iron, sensing big masses of metal nearby, which makes them invaluable in searching for ore deposits in the wilderness or weapons deposits. They can control metal, making it dance under their command – my favourite use of this is to open your enemies' belt buckles, making them trip over their own pants. There's also an offensive spell which enables the sorcerer to shoot out any metal objects as dangerous darts: nails, powdered gold... everything becomes a potential bullet.

The sorcerer of iron and flame is the profession you pick to be a Street Fighter: they can set fire to their own fists, or make their own fists iron, both to increase their unarmed combat effectiveness. They can also set fire to their swords, because flaming blades is just something you gotta have in a fantasy setting.

Lastly, the sorcerer of iron and flame has a few "meta-magic" resources available. A generic magical shield that weakens incoming attacks, the ability to sense when an object has been magically tinkered with, and the skill to dispel hostile enhancements cast on themselves or someone else.

That's the sorcerer of fire and flame: arguably, the simplest caster class. They don't have to deal with supernatural entities, and their spells are thematically very tight. The sorcerer is good with iron, and good with flame.

Next time: tracker and witch!