Diaspora by Byers2142

What, another FATE game?

Original SA post Part One: What, another Fate game?Fate seems like all we talk about lately. Looking at Amber leads to discussing it, Kult practically begs to be be run in it rather than it's current mechanics, and Evil Mastermind is in the middle of his Legends of Anglerre write-up. I wanted to show off another Fate game: Diaspora . It's an interesting game that shows what Traveller might look like run in the Fate engine, and since it's come up a few times lately I thought it'd be good to take a deeper look at it.

0.Introduction

quote:

Once there was a great idea. Once we played Traveller. We played it day and night. When we weren’t playing it we were rolling up characters for it or generating subsectors or designing spaceships. Who needed to level up, when you were happy your character had survived the generation process?

The introduction to Diaspora is more than the usual "we had fun making this game, we hope you have fun playing it" text a lot of RPG books open with. Sure, that's all there, but embedded in the introduction are a few clues to the mentality that went into producing Diaspora. The first paragraph above gives us the biggest insight; these are long-term Traveller players, building a Fate game. They care about the systems and stories more than things like character advancement. In fact, we'll see later that characters in Diaspora never advance mechanically; instead, they change .

Another thing that the introduction focuses on is that this is, as much as possible, a hard science fiction game. They seem really proud of that, in fact.

quote:

While not all of us had the same goals to begin with, we hammered out some objectives. First would be that the game retain as much of our previous tinkering as possible because it was really good tinkering. Second would be that the game would aim for the feel of hard science-fiction. Harder than Traveller, than Star Wars, than Battlestar Galactica. No quasi-magical anti-gravity. No inertialess drives.

Really proud of it.

The last thing they do is embrace the idea of player authority, to the point where there's no real default setting to the game. Instead, they give you a gaming system to build your own setting at the table and tie your characters to it, with everyone at the table getting equal power in the setting creation. Remember, these are Traveller nerds, so any time there's an opportunity to introduce design, they took it. Look back at that first paragraph. These guys enjoy making new characters, new settings, new spaceships. Is it really a surprise they threw all of that shit into their game?

1.Playing with Fate

In the first chapter, we get something... different than most RPG books. It's easier to quote the first paragraph to explain this:

quote:

Diaspora is a role-playing game. As such, it is a mechanism for collaborative storytelling, with a focus on hard(ish) science-fiction adventure. You build a universe, you build characters, and then you play with them in it. A game might last two or three sessions, or it might last more than twenty. Then you start over again. Fun is had, stories are told, lives are improved.

Yeah, that's the closest Diaspora has to a "What is Roleplaying" section. Instead, Diaspora assumes you know what a roleplaying game is and tells what's different. It's a nice change if you've been reading game books for a few years, but it does make Diaspora less beginner-friendly. One of the few real knocks I have against the game is that if you've never rolled the dice before you might not understand the underlying assumptions to a roleplaying game. As long as you have a few veterans at the table, though, everything should be fine.

The base mechanics of Fate are explained here, but also included are the authors ideas of how a game should be run. Throughout the game, we get bolded simplifications after rules or ideas are explained. For instance:

quote:

The guiding principle is “say yes or roll the dice.” What that means is, when a player has an idea about what he wants to happen, it can often be the case that what he wants doesn’t mesh with what the referee wants. In this game, we want you to quash that instinct to tell the player, “no.” Instead, look at the idea, ignore your plans, and either say, “yes” or set a difficulty and make them roll to see what happens.

Say yes or roll the dice.

There's a lot of talk in this chapter about sharing power between the players and the referee (GM), and the authors acknowledge that what works with one table might not with another. They want us to talk things out and behave like adults and friends while playing the game; it's rather nice to hear the optimism they have when talking about it.

quote:

We’re also, then, tacitly acknowledging that every table is distinct. We wrote this game and play tested it, so it reflects the interests of our table. Your table, however, will necessarily create a different game. That’s not just okay with us, or even expected, but rather that’s awesome. And so, in realizing this, we have decided to stay as far away from territory that belongs to your table as possible. Diaspora recognizes that almost everything past the mechanical is your territory.

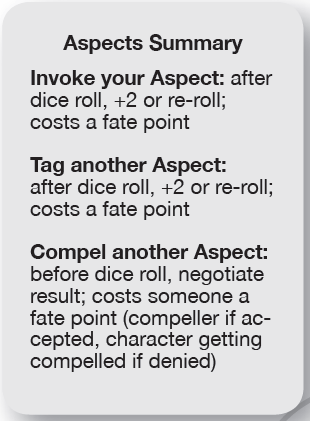

Once they finish explain the philosophy that went into the game, they get into the Fate mechanics themselves, and it's much as we would expect from a Fate game. The base mechanic is to roll 4dF + (skill level) and compare that to either a static difficulty or an opposed roll. In addition, all characters and a lot of things have Aspects that can be tagged, compelled, or invoked. Working with Aspects typically costs Fate points, and a brief breakdown is provided in a small sidebar:

Maneuvers are ways for players to put additional Aspects onto things. Set something on fire? That's a maneuver. Grapple with someone? A maneuver. And the nice thing is, that new Aspect can be tagged once for free. So if you blind a man, you can tag that Aspect next time to punch him in the face harder. Once the dice are rolled and Aspects played with, you end with the resolution. Your roll is compared against the difficulty or opposing roll. If you rolled higher, the number you exceeded the target by is the number of shifts. Some rolls use shifts for effect; damage, for instance, is based on shifts. If it's an opposed roll and the aggressor fails by three or more, it generates spin, which can be used in later rolls. Think of it as failing bad enough that you're off-balance.

The chapter closes with a brief discussion of skills. First, each character has an apex skill, something that he's better at than anything else. For a Fate point, players can make declarations with that apex skill, facts that are true. The referee can modify the declaration, but can't deny it. Again, it's all about player authority. Second, some skills might be limited or amplified by other skills; when we start dealing with the actual gameplay in chapter 4, I'll explain these ideas and how Diaspora does them a bit differently. For now, let's move on to the first mini-game the Diaspora offers us: cluster creation.

Next Time: We'll see how Diaspora creates the setting of the game. I need ideas, though! Give me some settings you've always wanted to see in a science fiction space game, and I'll show you how they can be created in Diaspora and folded into the larger cluster. I'll try to fit at least three in, more if I can.

Systems and...

Original SA post DiasporaPart 2: Systems and...

Before going on, let me just say thank you to The Saddest Robot , Mors Rattus , HitTheTargets , Count Chocula , Kestral , Tasoth , and Zandar for their contributions to the system ideas; I'm going to try to fit as many of your ideas in as I can. I really hope I didn't miss anyone, but if I did just chalk it up to me being a jackass.

Each chapter and significant section in Diaspora starts with a brief fictional snippet, one that ties to the section it prefaces. I'm including the snippet at the beginning of chapter 2 to give you an idea of how they read, and I'm going to pretty much ignore them until the very end of this write-up.

quote:

Ceva looked at the starmap the Tenbrean had given him. It was just a handful of circles connected by a few lines. “That’s it? That’s the universe? I see a million stars and this is the whole universe in six dots?”

“No,” replied the hairless and ancient youth, “not the whole. Man is out there on myriad stars. One of them is our home. But today this is all we can reach. One day we may break through that veil. Your world could be the Gate.”

2.Clusters

There are very few static pieces to the Diaspora setting, but those pieces influence everything that follows. There is a form of FTL travel, but it is very limited. In each system, there are two slipknots, on either side of the system and roughly equidistance from the system's center. Except for travelling the slipstream which is entered at these knots, all travel is roughly Newtonian in nature. And beyond that one limited form of FTL, science is grounded in our current understanding of the universe. There is no artificial gravity manipulation, nor artificial intelligences, nor anything that would require Star Trek techno-babble to explain.

Humans have populated the universe, but are now cut off from one another. They exist in clusters on connected systems, each with the two slipknots as noted above. The slipstream between the knots allows travel within the cluster, but travel to outside of it is not possible. In essence, for the purposes of the game this cluster mentality allows you to have a manageable-sized universe to operate in, unlike Traveller, for example, which has more sub-sectors than any group will be able to visit in the game.

In the typical Diaspora game, you'll spend the first session building the systems, cluster, and characters you'll be using. I'm going to deal with each piece in a separate post, but it's important to remember that this is all done at the same time. All told, this initial session usual runs 2-4 hours.

So, let's talk about systems. Systems are defined as an area of space bracketed by two slipknots. That's all we're told about them; the game leaves it to us to come up with everything else. Usually, systems are stellar systems like our own Solar System, but they don't have to be. The book recommends 6-10 systems be created, and I've found that the best way to do this is to double the number of players, including the referee. In this write-up, I'm supposing 4 players, so we'll be making 8 systems.

To start, each player is given 2 systems to generate. Systems always have three attributes, rated on a scale of -4 to 4. This scale is used because it's the range we get from a 4dF roll, and while we can just pick what numbers we want in each system (and for a few, I will be), the game suggests rolling the dice and working with whatever outcome you get. Remember what I said in my first post, this game is written by Traveller nerds and the randomized sector generation in Traveller is a big part of the game to them. It's not surprising that they ported it into Diaspora. What is surprising is how well they worked it into a Fate framework.

The attributes are as follows:

code:

Score Technology Environment Resources

-4 Stone Age No habitable worlds No Resources

-3 Metallurgy Barren World (no atmo) Multiple Dependencies

-2 Industrialization Hostile Environment Needs Imports

-1 Atomic Power One Garden World Almost Viable

0 Exploring the System One Garden World, Several Barren Worlds Sustainable

1 Exploiting the System One Garden World, Several Hostile Environments Rich

2 Slipstream Use One Garden World, Several Survivable Worlds One Significant Export

3 Slipstream Mastery Some Garden Worlds Multiple Exports

4 On the Verge of Collapse Many Garden Worlds All You Could Want

After you have your attributes, you come up with a name and a concept for your system. Let's say, for instance, that we rolled T0, E-2, R2 for our system. The player it's handed to, John, thinks on it, and decides that while a dangerous atmosphere would fit well with Hostile Environment, that's been done. What if instead it's the land that's the problem? He gets excited and thinks about it some more, and decides that the problem is there just isn't any on the sole inhabitable planet in the system. Ignoring any thoughts of bad Kevin Costner movies, John plows ahead. T-1 means they're roughly one step above our technological level, so how would they deal with Aquafina world? Ships, massive ships with human colonies on them. They'd get their food and resources from the ocean, which suggests their One Significant Export would be seafood.

Now that John has the attributes for his system and a rough idea of what they mean, he needs to generate two Aspects. It's suggested you come up with a quick description of system, maybe a paragraph, and then pick out two important facts from that to build your Aspects. John thinks about how he would describe the system, and two things stick out. First, the ships would probably form an almost familial feel to them, and so the strongest governing agency would be the ship captains. He likes that, so he decides to give the system the Aspect of Every Ship a Nation . He also wants to reference the system's chief form of export, so he calls his second system Aspect Fishing is What We Do .

And here's where the table comes into play. You see, these systems aren't created in a vacuum; you're encouraged to talk about them with everyone else at the table. So John gets this rough idea together, and then he shares it with the table. Paul likes the idea, and starts talking about what kind of adventures they could have in the system when George cracks a joke that maybe there are mermaids. The table pauses, and then our final player Ringo says, "Well, what if there are intelligent jellyfish-like creatures, mate? And the humans in their ships just don't know they're intelligent? Or maybe they just don't want to know it, since they're so delicious?" They all agree that this is a great idea to add to the system. Notice, the system is still very much like John imagined but now there's a new twist added in thanks to the table talking about it. Something like this is worth an Aspect, so they take off the Every Ship a Nation Aspect (although the idea still holds true) and add on the Aspect Intelligent Jellies? That's Stupid! Once things are hashed out, John writes down the current state of the system.

...

Fiji

T0, E-2, R2

Orbiting the star Fiji, you'll find the water world of Aquafina. The entire surface of Aquafina is submerged under the waves of a global ocean, but humans have found a way to adapt to its waves. All of humanity on Aquafina lives in great Ships, built to survive the worst of storms and hold thousands of people each. These Ships travel across the face of Aquafina, chasing the bounties of the ocean. The Fiji system exports most of its seafood catch to other worlds, selling plankton and seaweed as bulk nutrients and luxury items such as the famed Fiji Jelly to high-end resorts and restaurants. The Fiji Jelly in particular is highly sought after by out-system chefs for its delicate, smoky taste. There are rumors that the Jellies display possible intelligence, but prominent Ship captains assure the public that it is nothing more than cunning animal instinct that drives the Jellies.

Fishing is What We Do

Intelligent Jellies? That's Stupid!

...

At this point, Fiji is ready to be slotted into the cluster. We'll deal with that next time. For now, let me redirect your attention to attributes for a moment. Each attribute defaults to around 0 when dice are rolled, but you need at least a T2 for there to be slip-capable spacecraft. Therefore, if you make all of the systems and there are none at T2 or higher, then you change the systems with the highest and the lowest Technology score to T2. It's a quick change that ensures your game has FTL travel.

The other things to notice are the level 4 scores. These scores are rare, but a system with an attribute at level 4 has a massive effect on the game. A system with Resources 4 is nothing short of a treasure trove of goodies. It's got unlimited food, vast amounts of wealth, and unlimited power generation. You can expect heavy traffic through the slipknots of such a system, and players more than likely will end up here several times in their adventures. A system with Environment 4 has many worlds that are paradise. That means a large population and a heavy tourism market. Explaining why the system is like this is important; perhaps it was heavy terraforming, or evidence of technologically advanced inhabitants prior to humans? Either way, having more than one system in a cluster with a score of 4 in either of these attributes can destabilize the game balance some, and it's recommended that you don't do this.

And then there are T4 systems. All of those rules I gave you above, regarding FTL and artificial gravity? Throw all of those out in a T4 system. T4 indicates that the people of this system have moved beyond our current understanding of science. They're doing the crazy things never seen in hard science fiction, and because of that they're doomed. In essence, T4 systems are meddling in forces mankind can't possible comprehend, and they're going to pay the price for it. Perhaps they already have.

Paul rolled T4, E-3, R3 for one of his systems, and focuses on the technology first. In science fiction, he always liked the idea of anti-gravity, and so he decides that's the direction this system's top scientists focused on. They recently made a breakthrough, discovering what they called Gravions. Manipulating the Gravions, they could affect the gravitational pull in a discrete area of space. And then something happened, and they accidentally turned off the gravitational force holding their homeworld together. Boom, instant asteroid field. Those few people left in the system were those in small scientific colonies on barren moons. But Paul can't figure out a good way to explain that resource score.

He turns it over to the table, where John suggests that it wasn't an explosion, but an implosion that destroyed the homeworld. The Mistake (John likes Capital Letter Ideas) caused a small artificial black hole to form, and it's sucking up the mass of the system's star. There's a huge amount of energy flowing between the star and the black hole, and anyone insane enough to try it could use the side effects of that to generate massive amounts of power. Said insane people are found, and now massive industrial complexes line the very edges of the energy flow. Radiation counts are high and no one lives long in the factories, but the exports are a trillion credit a year business. Because of the danger in the system, there is little government oversight; smuggling and piracy are high in the system.

...

Regret

T4, E-3, R3

Push Button Apocalypse

It Really Sucks Here, but the Money's Worth It!

...

The key thing here is that while the system is T4, it's nearly worthless to the players. They can find remnants of the technology among the moons of the system, but most of what this system knew was lost. This is a good tack to take to make sure that the technology leaps a T4 system provide do not overwhelm your game.

I'm going to leave off here, as we're at the point where we start linking the systems together into a cluster.

Next Time: We build our cluster, I fit a second T4 system into the cluster and we see why pissing off a technologically superior civilization falls under the "Bad Idea" category. We see how well I do at fitting the rest of the system ideas into the cluster, as I've only fit two and a third in so far (combined portions Kestral and Zandar's ideas into Regret). Also, pictures!