Cryptomancer by BinaryDoubts

Mordenkainen's Magnificent Mining Rig

Original SA postCryptomancer posted:

Kill all the orcs, hack all the things.

Cryptomancer is, like the helpful banner above says, a fantasy roleplaying game about hacking. It was created by two infosec professionals - Chad Walker and "Timid Robot Zehta" (no, I have no idea either) and it shows - the game is fastidiously concerned with encryption, informational control, and hacking, with all the other fireballs 'n' swords stuff as a distant afterthought.

It's a really new game, so this will be more of an overview than an in-depth analysis (also, this fucker is 400 pages, and like half of it is a textbook about security). Oh, and if the game sounds cool to you, please support the authors! - The PDF is only

.

.

So, preamble out of the way, let's dive in!

The book opens with a nice introduction that sums up the two (sometimes conflicting) aims of the game: to provide an extremely detailed approach to intrigue-based campaigns, and also to have all the dungeon-looting fun of Every Other Fantasy RPG (tm).

One thing to note is that the writing is extremely clear and mostly free of typos (I only spotted a few mixed-up words across the 400+ pages, which is pretty impressive for a no-budget indie game). It's also a little dry and more than a little wordy. Here's an example:

Cryptomancer posted:

[Cryptomancer] is a game that providess avenues for players to play fantasy characters who attack and defend the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information systems that support kingdoms and factions. However, instead of adopting a “hacking as combat versus technology” abstraction that so many modern role-playing games adopt, Cryptomancer provides an unglamorous and unapologetic take on information security. This game’s rules and setting are informed by real-life information security principles, such as encryption and network defense, as well as intelligence community concepts, such as tradecraft and link analysis, all of which are presented in a context that makes sense for a high-fantasy setting rife with conflict and intrigue.

I'm skipping over the next section, which is literally titled "Obligatory RPG 101 Section" because, well, it's the Obligatory RPG 101 Section. Nothing new here. The next section is about player satisfaction, clearly laying out what players and GMs get out of a) traditional fantasy heroic stuff and b) espionage/intrigue challenges and stories. I like that the author clearly expresses that there's more to having fun than just "telling a great story" - that player enjoyment can also come from getting a kickass piece of gear, or beating a tricky combat challenge, or even just seeing the numbers on their sheet go up. Another nice thing that gets called out here: it's very hard to make a character who only excels at one part of the game (combat vs intrigue). I'm not totally convinced that's true (which we'll see during the mechanics chapters), but for now, it's a nice thought. Another key point is that there is no hacking skill: although there are a few spells to help with sneaky-type-stuff (and magical DDOS attacks - more on that later) everything to do with hacking and encryption is player-driven: if you want to find out the catchphrase, you have to go and find it. No "information gathering" rolls for you.

The next section talks a bit about high vs. low lethality campaigns, notes that players and GMs should all be on board with the tone of the campaign, but also lays out a key thematic element of the game:

Cryptomancer posted:

Cryptomancer is a pretty dark setting and includes mechanics conducive to a thematic death spiral. It’s only a matter of time until the oppressive powers that be wipe the heroic player characters off the map. This is by design.

Next time: what do you get when you cross Middle Earth with a mineral-based Usenet client? Cryptomancer's setting - industrialist elves, magic encryption, and more!

+10 to AES

Original SA post

Swords, sorcery, and infosec... let's read Cryptomancer! (Part 2)

A note on art - the book has some very nice full-page B&W sketches at the start of every chapter (all by Philipp Kruse), but that's it for art, aside from some diagrams that I'll be posting later. Since there's so little art in the book, I don't feel great about reposting it here. Apologies for the ol' Wall-Of-Text going forward. Anyway, let's find out how the hell internet hacking and fantasy pastiche fits together!

Setting Overview

The first sentence of this chapter doesn't fill me with confidence, given that it directly calls out the setting as being "bog standard" in many ways. They explain that it's a specific design choice, the idea being that players can feel comfortable with the background stuff so they can focus on the hacking/encryption/intrigue that's been sprinkled on top of Tolkein's grave like so much fairy dust. I'm not totally sold on this, and frankly the author doesn't seem to be either - there's more than a handful of references to the setting being, like they said above "bog standard" or "Tolkeinesque". If the author seems bored by his own setting, than maybe it's a sign that it's in need of a little more of a shakeup than "elves, but with Internet."

The setting is divided into two eras: the Mythic Age, and the Modern Age. During the Mythic age, things went pretty much like you'd expect: in the author's words, it's when the setting "conformed to fantasy genre tropes." Elves were elves, men were men, and there were plenty of dragons to go around. They mention that the history of the Mythic Age has been rewritten and argued over so many times that's impossible to know what's true any more, which rather conveniently saves them having to spend more than a paragraph talking about the Mythic Age. Regardless, the time of myths ended with the advent of the shards (Worm fans, take a drink - we're gonna be seeing that word a lot).

I'll let the author describe what the Modern age is like:

Cryptomancer posted:

The past is complicated, but not as complicated as the present, also known as the Modern Age. Things are considerably less epic and more existential than they used to be. The dwarves have become Medici-like merchants, the elves have become expansionist industrialists, and the humans struggle to maintain decaying feudal and caste systems in an era of information and social networks. The advent of the Shardscape, the magical equivalent of the real world’s Internet, has been absolutely disruptive to society. Technology, society, and identity are transforming much faster than the medieval mindsets of this game world can comfortably manage.

Risk Eaters

This chapter also introduces the putative villains of the game: the Risk Eaters. The advent of the Shardscape (coming up next, I promise) led to an explosion of complexity: local crises become global disasters, once-isolated villages join a thronging global economy, and instant communication has made war faster and more deadly than ever. Recognizing the threat posed (by, let's be honest, mostly humans), all three sentient races got together and agreed that the growing instability of Sphere posed a threat to the entire world. Out of the three races, a cabal of mages was selected to act as the realm's caretakers, working from a cryptomantic monolith. There, the Risk Eaters maintain a vast network of spies to maintain a continuous flow of information into "ancient dwarven decision engines" to help guide their decisions. Their actions are opaque and enigmatic even to their agents, but one thing is clear: you do not fuck with the Risk Eaters. They will murder you, kill your friends, and level your entire village if their machines tell them it will prevent a greater crisis in the future. It's unclear if their desire to protect the status quo reflects a benevolent impulse - that they're holding back some greater disaster by putting down popular uprisings, discrediting powerful leaders, and assassinating future heirs - or if they're just a bunch of assholes. Either way - don't cross them.

Cryptomancer posted:

Those who would dare to upset the delicate balance they have achieved chance the wrath of an all-knowing and all-seeing entity with limitless resources and unmatched aggression.

Cryptomancer posted:

Now steel thyself for some crypto.

SHARDS

Shards are rare crystals found deep in Subterran mines. Needless to say, the dwarves covet their monopoly on shard mining very, very jealously - they know that control over the shards is the only thing keeping their dwindling race relevant in the modern world. They're fabulously expensive, and only the very wealthy or well-connected can hope to have access to their own shards. Shards begin their life as a single chunk: the larger, the better. Shards must be perfectly cut into equal-sized chunks to function, but once you have at least two shards cut from the same whole, you've created a shardnet. (I'm so sorry for the amount of times you're going to see the word "shard" in the next section). Anyone clutching a crystal belonging to a shardnet can instantly and silently broadcast their thoughts to anyone else holding a piece of the same shardnet. Thoughts sent through a shardnet are called shardcasts (and those who use them are called shardcasters, natch) and they'll persist, echoing through the 'net for a number of hours equal to the number of shards that make up the net. They function regardless of distance, meaning they allow for the same thing that revolutionized the modern world: instantaneous communication.

There's a catch, though. Shardnets have no easy way to keep eavesdroppers out. Anyone holding one of the shards from a 'net can listen to any current echoes without being detected - so you if you're going to be conducting some skullduggery (which is apparently how everyone on Sphere spends their time) you've gotta start concealing your words from potential enemies. Enter: cryptomancy.

Cryptomancy

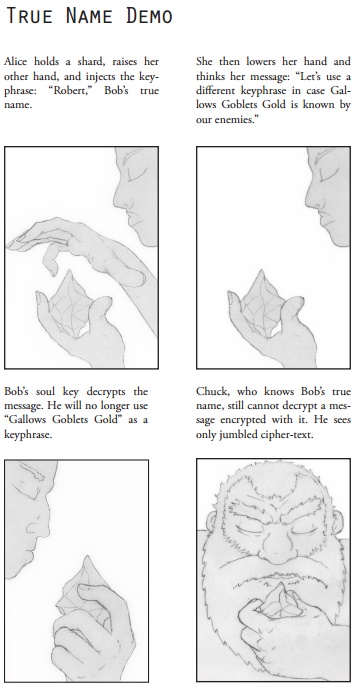

On Sphere, cryptomancy has existed for as long as written language. Anyone can do it, although it was only after the dwarves began to study the art that it began to be more widely understood and used. In its most basic form, cryptomancy enables the instantaneous encryption of a written, sensical (no made-up words) message from readable to gibberish (or clear-text to cipher-text, in crypto-speak). All you have to do is concentrate on your message, raise a hand, and the utter aloud a keyphrase. Anyone who knows or has ever heard that phrase will see clear-text when looking at the message, while everyone else sees gibberish.

There's no specific action required to decrypt cipher-text: if you know or have ever heard the keyphrase, you'll look at the cipher-text, "see" the keyphrase emerge from the gibberish, and then instantly perceive the original, clear-text message. Everyone can do this basic encryption/decryption trick, although most aren't any good at actually using it - think about how many people in real life have gotten hacked for having "password123" as their Gmail login.

Obviously, choosing a keyphrase is important. The book mentions "don't look a gift-horse in the mouth" as an example of a shitty keyphrase, since it's a common idiom. Instead, you should choose phrases that are unlikely-to-impossible to ever emerge, even accidentally, under any circumstances. This basic lock-and-key encryption is called symmetric encryption, and it works fine for low-level security, but it's easily broken by any number of methods - subverting (through torture/bribery/blackmail/etc.) someone who knows the keyphrase being the most obvious one. It's also not much use against the Risk Eaters, since they have agents who do nothing but gather local idioms, digest printed material, and eavesdrop relentlessly. They even have codebreakers who do nothing but write and recite nonsense phrases so that their organization has the largest possible knowledge base to use on intercepted encrypted communication. Remember, you only have to have heard the keyphrase once in your life to be able to use it to decrypt.

Keyphrase Espionage

That said, the weakness inherent in symmetric encryption can be used to your benefit. The book points out that it's great for mindgames: if you suspect someone's suborned a shard, you can use an intentionally weak keyphrase to let them eavesdrop on fake information, setting up an ambush for later. Of course, there's always the possibility that they'll know you're trying to fuck them and then purposefully avoid the ambush and so on and so forth. Mind-games aplenty already, and this is just the basic crypto.

Cryptomancer posted:

Unless it is dramatically appropriate, players and GMs need not actually articulate their keyphrases. It should be assumed that unless otherwise specified, a keyphrase for a specific cryptomantic task is strong and extremely difficult to guess. Clues about a specific actor, such as where she is from, what she reads, what she does, and who she knows, can sometimes allow an attacker to guess a keyphrase that actor might use, but generally, this is a shot in the dark.

The book also points out that the greatest weakness of a keyphrase isn't in its inherent complexity (since only the Risk Eaters stand a chance of guessing a very strong keyphrase), but in how it's handled. They have to be short enough to be manageable to share between parties, and they also have to be spoken out loud, making them prime targets for physical surveillance. And of course, the human element is always the weakest: there's the analogue methods mentioned above (torture, etc.) but also mind-reading magic and other fun fantasy bullshit to worry about. Oh, and I kind of touched on it earlier, but this kind of encryption also works over shardnets: you have to grab the shard, raise your hand, and utter the keyphrase. The shard will glow while the 'caster speaks the phrase, and then goes dark again. Until you release the shard, any message you send will be encrypted with that phrase.

I hope I explained this stuff in a relatively easy-to-understand fashion, but if not, there's some helpful diagrams coming in the next update. I'm happy to clarify or explain before then, too, so post away if you have any questions.

Next time: private-key... I mean, true-name cryptomancy. And diagrams. Exciting stuff.

Words that "defy logic and nature"

Original SA post

Asymmetric Cryptography for the Modern Elf... Let's Read Cryptomancer! (Part 3)

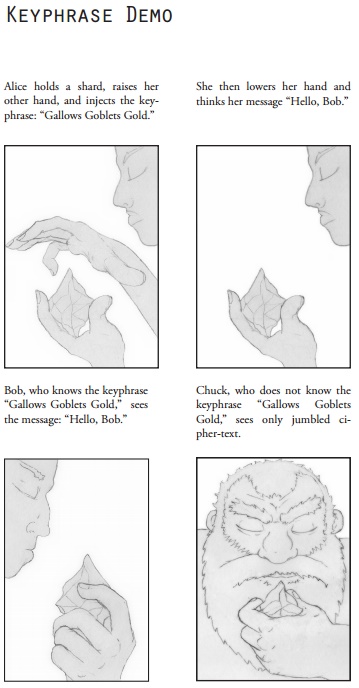

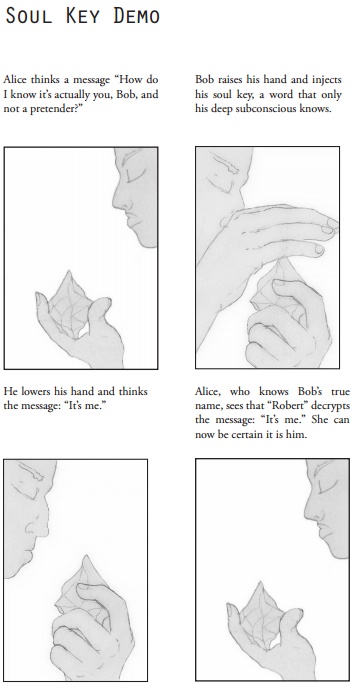

When we last left off, I'd covered the basics on shards, shardnets, and keyphrase encryption. Now, let's dive in a little deeper and see just how far the authors can contort their fantasy world to allow for another kind of encryption: private-key encryption! (But with magic). In the world of Cryptomancer, every sentient being has three types of names: common names, true names, and soul keys. The first is self-explanatory, it's the name you're given by your parents (or chose yourself) and it's usually shared freely. The second name is much more carefully chosen (and guarded) - it's your true name.

True names are chosen by the child's parents at birth (what happens if the mother dies in childbirth and there's no father present is unclear) and are entirely unique: whatever magical forces control the true name system simply won't allow for a previously-used true name to be assigned to the child. The child's true name is usually kept secret from them until they're old enough to understand how important it is - it wouldn't do to have your five-year-old shouting their cool new name from the rooftops. Again, there's nothing written about what happens if the parents die before telling the child their true name, but let's just assume that the God of Crypto will whisper it in the kid's ear if that ever happens. Anyway, true names are powerful (you can use them to target spells, for example) so they're usually kept secret except from your closest friends, allies, and confidantes.

Finally, everyone who has a true name also has a corresponding soul key. They're words that "defy logic and nature", which you can read as "the author didn't figure out a good explanation" or as a fun mystery. Either way, they're so powerful that you don't even know your own soul key - you can sort of evoke it, but you won't remember exactly what you thought or said. When spoken aloud, "time stops and all within earshot enter a sudden trance," which just raises all sorts of extra questions (can you chant your soul key to freeze a group of enemies? Do you freeze too? Does time literally stop while it's being spoken? etc.) exactly none of which are elaborated upon.

So this somewhat cumbersome system of two-name pairs is what allows Cryptomancer to include private-key encryption in its fantasy milieu. The system works like so: since soul keys can't be copied or stolen (with the exception of situations where your enemies are able to capture and torture you), it's a great tool for encryption. Messages that are encrypted using your true name as a keyphrase can only be decrypted by whoever holds the corresponding soul key, and vice versa. You can use the mechanism to either guarantee a message's sender, or guarantee a message's recipient. If you sign a message with your own soul key, only allies who know your true name will be able to read it, and they'll know with absolute certainty that it was sent by you (although they may not know if you were coerced into sending it). Messages signed with your true name can only be decrypted with your soul key, which means allies who know your true name can send you messages that are guaranteed to be read by one person and one person only: you.

Given true name cryptomancy's obvious advantages over keyphrase encryption, why wouldn't you always use it? The authors point out a few obvious reasons:

Cryptomancer posted:

• True name cryptography is not very convenient, especially when multiple parties of varying levels of trust are trying to communicate with each other.

• The more people that know one’s true name, the less secure and private a message is that is encrypted with one’s soul key.

• Messages insist on responses. An actor is more likely to read and act on a message intended solely for her, and therefore is more easily lured into dangerous situations.

• True names provide non-repudiation. Because the security inherent to true names is absolute, someone cannot

deny her true name if caught responding to a message encrypted with it.

• There are dangerous magic spells which require a caster to know a victim’s true name. The fewer people who know an actor’s true name, the less likely it is that the actor will be on the receiving end of such spells.

I should say that, as cool as I think a lot of the game's concepts are, the amount of hand-waving that you have to stomach to make any of this work is a little high. So many concepts are just tossed off as "well that's how it is", which starts to strain credulity after a little while. What I do like, though, is that they've clearly thought about each system and how it would work in the game, which lots of notes that explain their vulnerabilities and strengths when it comes time for the players to attack them.

And that about does it for the cryptomantic basics! Thanks for sticking with me through the weeds, here... up next is some more fluff on the three races of Sphere.

Our Elves Are Different

Original SA post

Our Elves Are Different... Let's Read Cryptomancer! (Part 4)

The first salvo of crypto spent, let's quickly get through the three racial chapters so we can get into the mechanics, shall we? Up first, our friends from Down Under, the Dwarves! In the world of Cryptomancer, Dwarves are "as diverse as they are numerous," which perhaps the first time that phrase hasn't been used to describe an RPG setting's humans. Dwarven society is split into clans, which used to be based on a common bloodline, but has now expanded to include many different families who share a common allegiance. The leader of a clan is called the mogul. The book goes to great length to stress that, even for the unusually-paranoid world of Cryptomancer, the dwarves stand out for sheer amount of time spent scheming. Power struggles and espionage are the rule of dwarven life - rare is the mogul who can rest easily.

Dwarven clanhalls are a clan's underground home base. Because dwarves love gilded shit almost as much as stabbing their enemies in the back, clanhalls are ridiculously ornate, with every possible surface being covered in gems and gold. The most common exports of clanhalls (and the source of their opulence) are precious metals and shardnets, the latter of which is the reason the dwarves have been able to stay competitive in the modern economy. Mining is considered indelicate now that the dwarves have moved on to the finer things, so being assigned to the mines is considered a severe punishment. Aside from raw resources, dwarves also export their engineering prowess: as is the law in settings without gnomes, the dwarves are the masters of steam-powered tech.

The dwarven psyche is dominated by a concern for aesthetics and pleasure - in this way, they hew closer to the traditional concept of elves than of dwarves. They look down upon humans and elves for focusing on material things, ignoring art and philosophy. Some long-beard dwarves pine for a return to the simple, bloody warfare of the Mythic Age, but that grows less and less likely by each passing day. The only way for the race to survive is to hold on to their economic dominance and never let go. The section on dwarves ends with some fiction about two dwarves who assassinate their dinner host - one is appalled, while the other is more shocked by the host's poor wine pairing and the blood that's ruined his coat. They prepare to fight some guards, and the story ends.

Elves

Cryptomancer posted:

The elves are the great parasite of Sylvetica.

If you chop the gigaphid out of the tree after a few years, it can be reared as an enormous and intelligent winged mount - something that gives the elves undisputed air superiority in battle. But if you leave it trapped for a solid decade, it will become a giant fount of soma, the single most important commodity on the planet. Needless to say, the elves took to gigaphid rearing with a vengeance. Gigaphid mounts and soma production has helped assure their importance in Sphere society, but it's also resulted in the slow death of their home forest. Now, miles of deadwood are all that remain of their once-verdant home.

Elves don't age physically past 40, but their minds start to go at 120, and few survive to 150. Elven society is tribal (note: also described as "diverse as they are numerous") and based around soma production. Tribes have a single leader - called a speaker - and a council of elders as advisors. The speaker's role isn't fixed by vote or law and can instead gradually shift as one's influence waxes and another wanes. There's no formality, no ceremony, but everyone in the tribe simply knows when a new speaker has taken over (which confuses other races' attempts to infiltrate or suborn the tribe's power structure). Tribes built out around the soma tree, living in nearby hollow trees and mushrooms and travelling by strings of ladders and bridges between the rotten treeline. Larger tribes have enough territory to also practice gigaphid ranching. The trees holding infant gigaphids can then become staging grounds for warbands, or tactical goals in internecine struggles. As a people, elves are humorless and unemotional. They don't mind humans, but really hate dwarves, who they think have fallen from paragons of might to a group of conniving epicurians. The section ends with another bit of fiction - an elf warrior bargains with some gnolls that they'll leave the village if they win a duel. The elf wins, the gnolls turn to leave, and then the elf commands her hidden warriors to cut the remaining survivors down with poisoned arrows.

Next time: Humans and Risk Eaters!

Risk Eaters

Original SA post

HUMAN & Friends: Let's Read Cryptomancer! (Part 5)

They're humans. You could probably write their chapter yourself, since they share the same traits in every fantasy RPG: they're numerous and adaptable. Or, in the words of the book, "populous, diverse, and distributed". They aren't new on the scene, at least - the book mentions that they were around during the Mythic Age, although neither dwarves nor elves took them seriously. During that time, humans were looked at as clever monkeys, basically. Taking advantage of their weakness, the other major races manipulated them, setting them up as proxy kingdoms to use as a bulwark against enemy action or orc invasion. This plan backfired when humanity wouldn't stop growing, and the once-proxy-kingdoms soon became the dominant force in the world. Now, Sphere is dominated by overcrowded, violent industrial cities and torn apart by warring nations and city-states. It's now humanity's world - the other races are just living in it. Humans tend to feel closer to dwarves, who they trust (for some reason) than they do to elves (who tend to spook humans because they avoid displaying strong emotions). Since there's so many "others" to hate ("elves, dwarves, soma addicts, cultists, mages, monsters, etc."), intercultural/interethnic racism never caught on, which is nice. (Kinda.)

Human cultures are apparently "as varied as they are numerous", which makes the book three for three on reusing that phrase. I'll just quote the book on how most human societies are structured:

Cryptomancer posted:

...the dominant human culture is based on the agriculture, industrial development, and military might needed to support enormous city-states best described as Borgia-era Italy meets Aztec empire Mesoamerica. Nearly three quarters of humans live in massive city-states with populations so large and wily that they can only be managed by a powerful state apparatus: an army of constables, seneschals, and bureaucrats answering to a ruler whose authority is absolute. Indeed, this is one of the primary features that distinguish humanity from the other noble races: the sheer amount of effort and resources humans spend on containing and controlling each other.

Because humanity faced repeated cycles of near-extinction during the Mythic Age, they're easily swayed by apocalyptic thinking, rarely thinking of long-term consequences. In this way, they differ very little from the humanity of Earth. Cryptomancy (and shard communications, as mentioned above) has also allowed a flourishing of revolutionary and philosophical dialogue within the underclass. Although on the surface, humanity remains "ignorant and authoritarian", new and strange ideas are constantly bubbling up in secret. Change, perhaps, is coming to the realms of Man.

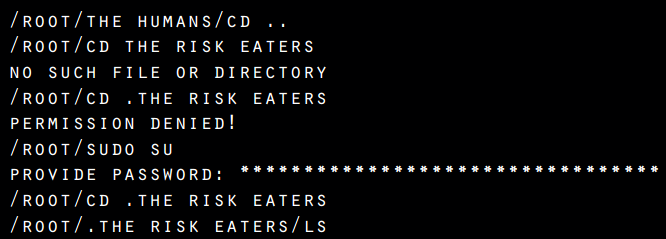

The Risk Eaters

All of the chapters have these fun command-prompt table of contents. The one for the Risk Eaters even requires a superuser to access, which is a fun touch.

The Risk Eaters chapter is somehow even more vague than the preceding racial chapters: it basically tosses a few cool ideas at you and then leaves it up to the reader to figure out how to actually use them in play. If you don't remember, they're basically the villains of the setting - they're what would happen if the Gestapo had access to the Machine from Person of Interest.

The first component of the Risk Eater infrastructure are the Strangers, who are the people destroyed by the Risk Eaters. They may have witnessed something they shouldn't have, or even double-crossed a Risk Eater agent - either way, they're screwed. Their voices, memories, and faces have been distorted by cryptomantic magic, rendering them monstrous and forcing them to the very outskirts of their former community. Sometimes they form small communities, although they can never bring themselves to trust the other Strangers - for all they know, their new friend is still working for the Eaters. Some are offered a chance to decrypt their past in exchange for committing an atrocity for the Eaters, but most are left to live out a miserable cursed existence. Strangers entirely shunned by normal society: one thing everyone knows is to never interfere with the Risk Eaters.

Then, there's the confessional. Most know better than to confess to a priest - they're human, after all, and fallible. Instead, they confess by whispering into the Shardscape, encoding their confession with the Cipher of Absolution: seven random words, of which one must be the name of the god they wish to confess to. Only then, the priests say, can they be absolved. The unwritten implication is that the Risk Eaters have their codebreakers listening, hoping to hear an encrypted confession that they happen to know the keyphrase to. The problem with that premise is that - even if we're generous and say that there's only one god, and that His name is always spoken first - that still leaves a phrase of six random words. There are 1,000,000 words in the English language, but let's cut that down to, say, a vocabulary of 20,000. 20,000^6 (six-word phrase) equals 64 septillion possible phrases (64000000000000000000000000), which seems impractical to work through, regardless of how many codebreakers the Risk Eaters have dedicated to doing nothing but reading and writing these phrases. (Let alone the issues you have with dialects, other languages, etc.) It's kind of a moot point because nothing about this setup is ever mentioned again, so I'm just guessing this is what the authors were trying to imply.

Cryptomancer posted:

Te most hallowed places in Subterra are the shrines of the Iron Seneschals, steam-powered creatures imbued with the spirits of long-dead dwarven heroes of the Mythic Age and equipped with apparati allowing them to listen and speak. Each of the seneschals is a steamwork leviathan protruding from cave walls, eternally powered by the flux and heat of rivers of lava. Teir shrines, scattered throughout the world’s deep, are where dwarves and even some surfacers go to seek the wisdom of immortal, impartial sages.

Finally, there's a bunch of RPG Fiction (tm) that I won't bother with, except to quote a telling bit from the Risk Eater's dogma:

Cryptomancer posted:

"I wish the people could be trusted to make their own decisions, but they cannot.

I wish our enemies would never have been born..."

"That, we can do."

So all that said, I decided to put in a little work and whip up the kind of GM aid that I think the book could really have used. I put together a Technoir-style transmission/plot creator for Brink, a town that's literally on the edge of the world. You can use it to generate intrigue for your games, or just as bit of inspiration. Take a look!

Clicky for PDF

Making a hacker in 11 easy steps

Original SA post

Making a hacker in 11 easy steps… Let’s Read Cryptomancer! (Part 6)

First off, I’m just going to plug the gazeteer/intrigue generator that I wrote for the last post – the author of the game saw it on Reddit and asked to put it on the game’s website, which is pretty neat. And now… mechanics.

The book introduces the mechanics by intertwining them with character creation, so you’re learning about each new concept at the same time that you’re building that part of the character. It’s not a bad idea but I always find it a little annoying – I’d rather have the rules be a standalone reference section and the character creation be a short checklist or something, rather than having the two awkwardly mingled together. Both the character creation and the mechanics are pretty simple, though, so I can’t complain too much.

Character creation starts off with the usual suspects: name, race, appearance. You also have to pick a true name, which you’ll use for soul key encryption once the game starts. Racial choice doesn’t affect stats or mechanics in any tangible way, which the authors even acknowledge “feels wrong”, but I think it’s a good call. PCs should be probably be weirdos, and if that means an agile dwarf or a studious elf, so much the better! They also provide some Dungeon World-style appearance descriptors to choose from, although you can of course ignore their suggestions if your ~perfect hairstyle~ isn’t listed.

I’m going to quote the author here on character inspirations:

Cryptomancer posted:

While Cryptomancer is a tried-and-true fantasy game, it is also informed heavily by ideas from different genres including heist movies, spy thrillers, police dramas, science fiction, and historical non-fiction, not to mention our own experiences with information security. So don’t feel you need to limit your character idea to fantasy conventions, unless that’s exactly what you want to play. Instead, play the character you want to play and just dress it up in medieval fantasy trappings if necessary.

Stats

So, stats. You have four core ranks: Power, Speed, Wits, and Resolve. Pretty sure y’all can figure out for yourselves what they each represent. The game does the FATE thing where you give each stat a descriptor that also corresponds to a numerical value – each rank is either trivial (4), challenging (6), or tough (8). These are the same descriptors used to determine a challenge’s difficulty, which is nice. They make more sense when applied to difficulty than to skill – exactly what a “challenging” core rank means is a little confusing (for the record, it’s for stats that are neither weak nor strong). The words don’t really matter, since you just write down the number, but I wish they’d picked better words. Novice, Apprentice, Master (or similar) would be much clearer!

Anyway, they advise you to fill in some sentences to figure out how to assign your character’s stats. For instance, these are the questions for Power (general muscularity):

Cryptomancer posted:

It is __________ to overpower this character.

It is __________ to pierce this character’s defenses.

It is __________ to kill this character.

[img]//i.imgur.com/vcFuSgB.png[/img]

In case you can’t see the image, the attributes are: Wits: Knowledge/Cunning, Power: Strength/Endurance, Speed: Agility/Dexterity, Resolve: Presence/Willpower.

Attributes can go from 1-5 (with 5 being the best), and you have points to distribute between each pair equal to the value of the governing core rank. If you have a Wits of 8, that means Knowledge and Cunning have to add up to 8: 4/4 works, as does 5/3 or 3/5. I love this system of derived attributes – it’s quick to explain, makes some intuitive sense, and also neatly allows characters who are both strong in the same core rank to still be distinguished from each other. Each of these attributes also governs four subskills, which aren’t given any kind of numerical rating – they’re more listed to give you a concrete idea of what each attribute governs, I think. I’m gonna run through these real quick, just pausing on a few skills that are worth discussing

Wits

Knowledge is all about, well, knowin’ things. It governs Alchemy (and you know there’s a potion-brewing subsystem coming up), Craft (making things), Medicine (healing things), and Query (finding things on the Shardscape and solving logical puzzles). Cunning governs your sneaky skills: Deception (lying and disguises), Scrounge (finding stuff), Tracking (finding people), and Traps (you can guess).

Speed

Agility: Acrobatics, Athletics, Escape Artistry (getting out of tight spaces… feels like this should have been rolled in to another skill), and Stealth.

Dexterity: Fired Missile (a weird way to say “archery n’ shit”), Lock Picking, Precise Melee, and Sleight of Hand.

Resolve

Presence: Beast Ken (taming and controlling animals), Charm (charisma), Menace (intimidation), and Performance (dancing and theatre and other boring shit players like to do sometimes).

Willpower: No skills, but your starting Mana Points equals 5 + Willpower. You also use it to resist fear effects, if your GM uses them.

Power

Strength: Brute Melee, Feat of Strength, Thrown Missile, and Unarmed Melee.

Endurance: No skills, but your starting HP equals 5 + Endurance, and you use it as a fortitude roll if needed.

I should say that this is where the organization starts to get a little crazy. You have to skip down to the Combat chapter to find out how much HP you start with, and waaaaaay down to the Magic chapter to find out the same for MP. (At least they use the same formula). The book has the Combat and Equipment chapters before the Talent chapter (perks, basically) and the Magic section is out past the Downtime rules. It’s not hard once you know how it’s laid out, but it is a little weird if you’re just trying to follow along and make a character.

Doing Things

So: how do you actually use these skills to do stuff? Well, the game has one of the most unique dice systems I’ve seen in a while – still deciding if it’s cool or badly overcomplicated. Basically, when the GM calls for a skill test, the player will always roll five dice and look for at least one success. Before rolling, you assemble a pool of d10s equal to your attribute rank, and then add enough d6s to get you to a total of five. These extra d6s are called fate dice, since they represent the little bit of extra luck heroes always have in fantasy stories.

Example: If you’re making a Feat of Strength test, and your Strength is 4, your dice pool is going to be 4xd10 and 1xd6. Remember those descriptors from earlier? Well, they decide the number you need to roll to have a die count as a success. A Trivial test requires a 4+, a Challenging test requires a 6+, and a Tough test requires a 8+. You’re just looking for a single success on any of your dice – multiple successes only make things more dramatic. There’s a catch, though: rolling a 1 on a die counts as a botch, which cancels out a success. If you have enough botches that your overall result is in the negatives, it means you not only failed, but that your failure was spectacular.

Another wrinkle: fate dice don’t work like your d10 attribute dice. Fate dice only succeed on a 6, regardless of the difficulty (so even if the task is Tough, a 6 still counts as a success). On the other hand, a roll of 1 or 2 counts as a botch – so relying on Fate is a sucker’s game.

So there’s the basics: roll five dice, look for successes, and hope to God you don’t botch things up too badly. Opposed checks are basically the same, except the GM doesn’t set a difficulty to, say, overpower an enemy: the difficulty is just equal to their Core rank – nice and elegant. There’s also rules for long-term skill tests and group tests and what have you but in the interest of time I’m going to skip over them.

Writing this out kind of solidified my feelings on the core mechanics, which is that there’s a nice elegance to the way difficulties and ranks tie together, but that it seems a little awkward in practice. I’ve never played the game so I can’t say for certain, but my feeling is that assembling die pools and quickly parsing the results would be a major slowing factor. The fact that fate dice use different rules for success/failure is annoying, too – I wish they’d found a way to have them use the same resolution system as d10s. (I can’t immediately see a problem with having the fate dice work like shitty attribute dice – they’d be useful for trivial tasks, dicey for challenging tasks, and useless/dangerous on tough tasks). Overall, though, I like a lot of stuff about the system! The skill list is to-the-point and laser-focused on the kinds of things the PCs will spend their time doing: mostly, skullduggery.

Next time: more character creation! Talents! Magic! Gear!

More Characters, More Creation

Original SA post

More Characters, More Creation… Let’s Read Cryptomancer! (Part 7)

First off, something kinda cool – the author reached out to me on Reddit to say he was enjoying the review, which makes the fact that I’m about to dump on the game a little awkward. If you’re reading, Chad, I love your game, but the Talent system… well, I’m not much of a fan. He also gave me permission to include some of the art, which I’ve done below – I’ll sprinkle some more throughout my future posts because I think it’s all pretty awesome.

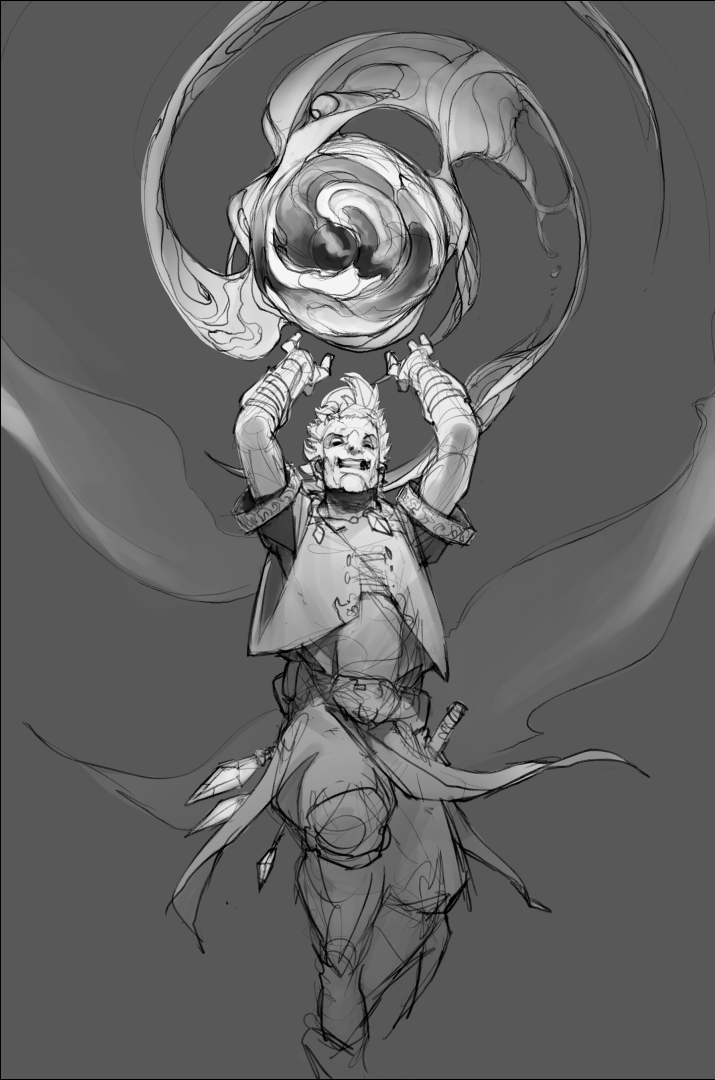

A Risk Eater agent using the Dissemble spell, which is some spooky fuckin’ shit, I tells ya

New characters begin with a pool of 10 points to spend between Talents and Magic, which is interesting: if you want to focus on magic, you’re going to be significantly less versatile and skilled than pure martial characters. So: Talents. They’re kinda like Feats or Advantages or whatever – little perks that give you specific advantages in specific situations. I’m not going to describe every one (since this book just came out, and since it’s hard to summarize when each talent is already one or two sentences), but there’s a few distinct types I can sum up:

- Skill talents. These are talents like Artisan, Entertainer, Grappler. Basically, you get to ignore one botch roll when using a specific skill. For instance, Grappler lets you ignore 1 botch for all Unarmed Melee skill checks. Not super exciting, but still a reliable way to make your character more skilled in a specific area. These talents mostly cost 1 or 2 points. I’d say like half the talents fit into this area.

- Stat talents. These let you use one stat instead of another under specific circumstances – stuff like using Strength instead of Presence to make Menace skill checks. Martial Artist lets you use Dexterity instead of Strength to make unarmed attacks. There’s also the 2-cost +1 HP or +1MP talents that you can take a bunch of times if you’ve already taken the talents that interest you otherwise.

- Magic talents. There’re only a few of these guys. Adept lets you spend MP to convert failed rolls to successes, while Bottled Magic lets you cast spells into alchemical bottles. Sanguine Rite lets you convert HP to MP, and Spellbreaker lets you immediately gain initiative when someone else starts casting a spell.

- Battle talents. You can probably guess what a lot of these are like – deal more damage with your fists, cleave through multiple enemies with big weapons, etc.

- Human shield talents. For some reason, there are three different kinds of human shield talents. One lets you use enemies as a shield, one lets you use friends as a shield, and one lets you use yourself as a shield.

- Fucking stupid talents. These are talents that no one should ever take for any reason. For example: Polevaulter, which lets “[a character] use staffs and spears to leap heights and distances that others could not even attempt.” Is polevaulting a common occupation in Sphere? I’d also lump Codebreaker into this category, which gives you a 1% chance to just automatically know a keyphrase. It’s too low a chance to ever be realistically useful, and even if it does work – all it lets players do is short-circuit a GM’s cool plot. One last entry to the Hall of Bad Talents: Gross, which lets you automatically succeed on Willpower checks involving gross-out situations. Do not take these talents.

Doesn’t this guy look like he’s having the time of his life?

Magic

In Sphere, fewer than 1 in 50 people possess any magical acumen. They cast spells by gesturing symbols into the air and speaking in a forgotten tongue. Magic isn’t seen as inherently good or evil – it’s a tool like any other, and its uses are hotly debated in Sphere. The book points out that while a healing spell is great, but how does the healer who makes her living doing surgery feel about a bunch of white mages running around, ruining her living? The state obviously has an interest in controlling magic, but just as they can’t outlaw shard communications for fear of falling behind economically, they know businesses will leave if they aren’t able to use their customary magic to conduct business. As always, I wish there was a little more detail given, but it’s still nice that there’s some thought put into how magic would affect society.

Mechanics! Characters begin the game with 5MP, plus whatever their Willpower rank is (between 1 and 5). Spells cost between 1 and 5 mana, and mana recovers very slowly – only coming back when you spend a session of downtime meditating (time that could be used looking for leads or networking). Mana potions are rare and expensive, which leaves soma as a common option for mages looking to cast more than a handful of spells before taking a nap.

I’m going to go through the spell list, but I’m only going to talk about the really cool and unique spells, skipping over the stuff you’ll find in other games. (Don’t think this thread needs another summary of a Fireball stat block!) Up first: cantrips.

Cantrips

Cantrips all cost 1 MP to cast, and 1 Talent Point to learn at character creation.

Babel: The caster touches the target’s neck and speaks a keyphrase. Until the caster dies or revokes the spell, everything the person says or writes will look and sound like complete gibberish to anyone who doesn’t know the keyphrase. You have to make an opposed Willpower vs. Resolve skill check against an unwilling target, but after that – the effect lasts forever, which seems pretty crazy. You can use it on yourself, too, if you want to do some cryptomantic business without being eavesdropped on. This spells seems crazy useful and crazy overpowered. If you win one contested roll, that person is effectively unable to communicate forever. I’d make this spell last only until the next dawn or something similar – it seems incredibly useful both offensively and defensively.

Denier: The caster holds onto a shard and basically DDoSes it. You make a Willpower check against a difficulty based on the size of the network, and on a success, no new echoes can be broadcast for the next turn. Remember that you can also use shards as a walky-talky, more or less, so you can use this spell to short-circuit an enemy’s command structure. It’s not effective to take down a shardnet longterm (although there are methods for that coming up!)

Dissemble: Same as Babel, but for a face: after succeeding on an opposed check, the target’s face will be encrypted into an unrecognizable jumble of shifting facial features. Even those who know the target will still feel they are looking at a stranger, regardless of other distinguishing features (tattoos, clothes) that may exist.

Messenger: This cantrip summons a “small and resourceful” animal that will do everything it can to deliver a small object to someone whose true name is known to the caster. They travel very, very fast (quick as a hawk) and are generally ignored by the populace (it’s implied they look like rats), but perceptive enemies do have a chance to roll against their Agility to detect their presence.

Tracer: Lets you divine the rough location of every shard in a given shardnet. Bounty hunters often combine this ability with Messenger (having the messenger familiar bring a shard) to track down their targets.

Basic Spells

Basic spells cost 3MP to cast, and 2 Talent Points to learn at character creation. A lot of these are your fantasy workhorses – magic armor, heal light wounds, etc. I’ve picked out the fun ones:

Bloom Bomb: Two words for y’all: Weaponized. Flowers. Basically, this spell summons an explosion of dangerous flora in, on, and around a given target, which is pretty :kickinrad:. It can summon poisonous death gourds, entangling creep vines, or firey dragon pods, all of which sound like things I would not like to be surrounded by. It’s not stated, but I wonder if you could summon non-deadly plants. Would be a great spell for mass agriculture if you could just summon a field’s-worth of quick-growing wheat (or whatever) on a whim. (If I run this game, I’m ruling that you can also summon pumpkins, because I imagine it’s very painful to have 50 full-size pumpkins dumped on you, and also hilarious).

Maze: Like Dissemble and Babel, but for an entire entrance. You can turn the door leading to your secret clubhouse into an Escheresque nightmare at a whim, which is cool – but there’s also nothing stopping the Banksy of Sphere from running around, encrypting every door he sees while chugging soma. You could probably ruin an enemy city if you sneak a few mages in during the night and have them encrypt all the entrances to the barracks and keep. Probably another spell that needs a little nerfing to prevent shenanigans, I’d think.

Shadow Cache: I don’t know why, but I’m a big fan of shadow-based magic. This spell lets you hide objects within a shadow, creating a cache that can later be accessed from any shadow in the world. The contents of the cache can take some time to materialize, depending on how you roll, and you can only use shadows that have been “stationary for at least a day” (there’s a can of worms if I ever saw it), but otherwise – it’s a dope magic box that lets you literally pull rabbits (or swords) out of a hat. Not too powerful, but very cool.

Shard Scry: You can grab a shard and see everything that every shard in the connected network perceives, as if you suddenly have access to some magic-ass security cameras. Obviously great for spying, but I’d imagine it’s also useful for sysadmins or handlers, who could use the shards as “eyes in the sky” to literally watch the backs of her agents. Could also work as a city-wide surveillance system, if you have enough mages working in shifts.

Shard Spike: This lets you embed lethal malware into enemy shardnets. Using the spell lets you create an encrypted echo that looks very similar to any other in the ‘net. When it’s viewed and decrypted (you can use your enemy’s true name, if you know it, to make sure they’re the ones to see it) the caster is alerted, and the enemy takes 4HP of psychic damage, which is a lot – remember, you only start with 5HP + a max of 5 more. I love the idea of psychic traps, but there’s also not really any way to avoid a shard spike, since as written you can’t choose to not decrypt a specific echo. I guess the advice is “don’t let a hostile actor get access to your shardnet and you won’t get psychically stabbed in the ear,” which is fair enough.

Greater Spells

Greater spells cost 3 Talent Points to acquire and a whopping 5MP to cast. They’re so big and powerful that their backfires can be especially unpleasant – the author includes a few ideas for possible backfires for every spell, which I quite enjoy.

Dead Host: Transfer your consciousness into a fresh humanoid cadaver. I love this spell – it’s creepy, thematic, and not ludicrously powerful. I can definitely imagine a City of the Dead that’s run by networked necromancer-slaves, operating hacked-together corpses to carry out their master’s dark bidding. (Or whatever). Favourite backfire: The ol’ Freaky Friday, when the cadaver’s soul gets resurrected in the caster’s body. That has some serious potential.

Mind Write: A classic. Insert false memories or erase real ones – up to a week’s worth forgotten at max successes. Favourite backfire: Caster accidentally inserts a Manchurian kill-switch in herself instead of her target. (I like that they just straight-up call it Manchurian.)

Name Wraith: This is pretty much the primo “be a dick” spell. The caster speaks the true name of their target and belches up a viscious black wraith, who will torment the target on the caster’s behalf. At low successes, the victim unwittingly starts encrypting everything with a keyphrase chosen by the caster. At high successes, the wraith will whisper orders in the victim’s ear, forcing them to become suspicious and hateful of their friends and to become susceptible to basic orders. Favourite backfire: The wraith colludes with the victim to torment and deceive the caster. Imagine a pissed-off genie and your worst enemy working together – might be time to cast Dissemble and disappear for a bit.

Shard Warp: I read the first sentence of this spell description and really hoped it was some Tron-enter-the-Internet shit, but it’s more like a fax machine than anything else. You can teleport yourself (but not your clothes) through a shardnet and reappear next to a shard that sent a recent echo. If you only roll one success, you take some serious damage from the trip, while a high-success roll means you can choose an exact place and position to reappear. No matter what, you’re arriving Terminator-naked, so better hope you’re ready to fight or run when you get there. Favourite backfire: Caster gets stuck and becomes a bodiless consciousness existing in the shard (TROOOOOOOOOOON!)

So that’s the cream of the crop, spell-wise. While I think some of the subterfuge-related spells are more powerful than they need to be, on the whole I’m a fan of how appropriate to the setting the spellbook is. Oh – there’s ritual magic, too. No rules or guidelines for it but if your players ask where some magic shit comes from, just wave your hands and say “ritual magic” until they shut up.

There’s enchanted items, which are supposed to be rare but not impossible to find, and also relics, which are more on the “enchanted superweapon buried by an ancient civilization for being too dangerous” side of things. Favourite item: the Death Draught, which is an enchanted horn that springs eternal with healing potions – but only refills every time its owner kills another mortal. Favourite relic: The Midas Engine, which is a dwarven machine that chews up people and spits out 1,000 golden coins of any chosen design. It doesn’t have a ritual cost, but it does have a moral one – i.e., feeding people to a machine to make money should make you think twice about your life choices.

Next time: the end of character creation! (I promise). Also combat maybe?

Stuff and Blood

Original SA post

Stuff and Blood… Let’s Read Cryptomancer! (Part 8)

Shoutout to Philipp Kruse, who did all of the book’s art

Stuff (or equipment, if you prefer words that are less fun to say) is the lifeblood of the adventurer. Everyone loves acquiring shit, everyone loves cool swords, and no one will turn down a gleaming pile of loot. Cryptomancer recognizes that, hey, gear is cool – but it also doesn’t drown itself in mechanical minutia to describe how one greeble is different from another.

Gear has two components: qualities and rules. Qualities are basically flavour descriptors, stuff like “Elven made” or “Named”. Doesn’t change how a piece of kit works, rules-wise, but it’s a great way to encourage players to think about and characterize their gear beyond just “+1 to killing”. You have spots on your character sheet for trademark weapon and trademark outfit, so you’re encouraged to use qualities to flesh out your character’s particular look. (Too many RPGs ignore the importance of fashion in making a cool character!)

Rules are similar to tags from Dungeon World in that they’re simple descriptors that can meaningfully change how a piece of gear works. (Unlike Dungeon World, all the tags have defined mechanical effects). For weapons, you have rules like “dirty”, which means you can use it to shank someone in a grapple, “overwhelming”, which means it can only be parried by shields or other giant weapons, and “balanced”, which means you can throw it at someone up to medium range. (Not sure that’s what balanced usually means when you’re talking about swords, but I’ll take it). There’s a weapon list, but it’s more intended to show how you can combine tags to make distinct weapons. A mace is described with brute melee, damage +1, melee, and short, while a halberd is described with brute melee, cumbersome, damage +2, melee, overwhelming, strength req: 3, and two-handed.

I like this system a lot, but wish there were a few more tags – something for reach weapons, perhaps, or tags that grant unique actions in combat. Regardless, it makes it easy to just grab a few tags and throw together a sword – you don’t need to keep the equipment list handy. Armor has a similar system, albeit with a much smaller list of tags. Pretty much just different kinds of deflection, some agility/endurance requirements, and a tag describing whether or not it’ll draw the attention of security personnel.

Cryptomancer posted:

Generally speaking, ammunition is not fun to track, and bolts, arrows, and stones can be recovered after battles, so it is recommended that GM’s and players just trust in the universe and not bring up ammunition unless dramatically appropriate.

The Stuff chapter rounds out with a list of gear, but it’s all pretty much bog-standard adventuring stuff – potions, poisons, a few bombs, lockpicks, and so on. Same as with arrows, the author notes that they list medicine kits and not individual bandages because gear is supposed to supplement the character’s abilities, not create more bookkeeping. The only actual consumables are bombs and potions, which obviously are used up after being thrown/quaffed.

Combat

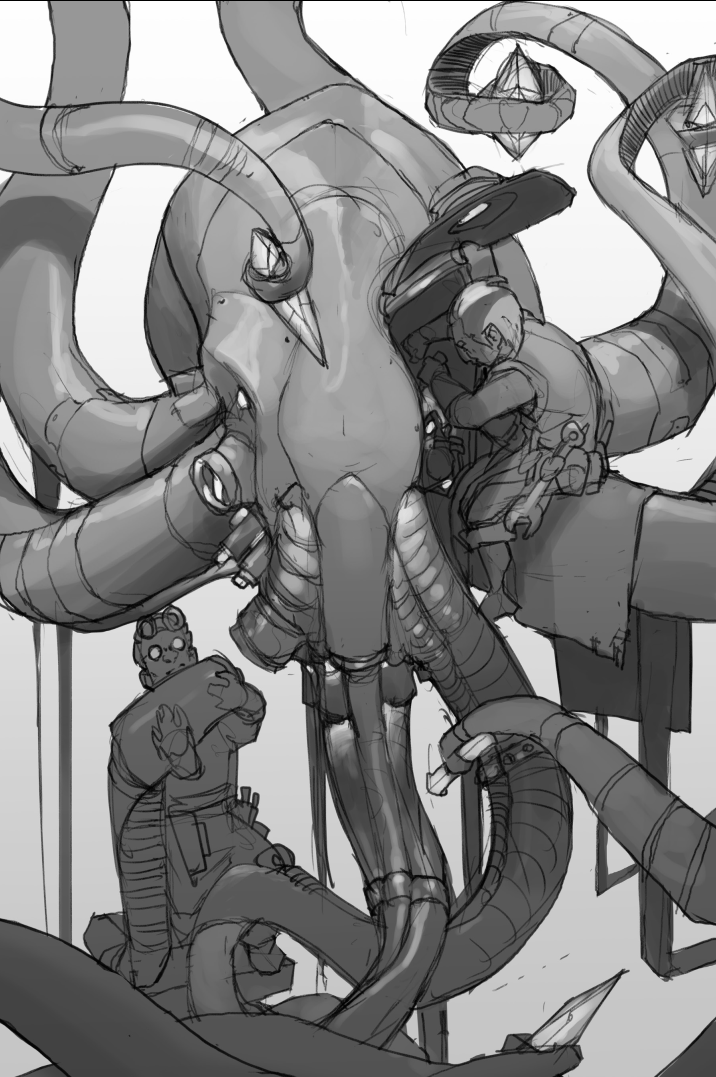

Love the sense of motion in this one. Also, the severed hand.

Cryptomancer posted:

Let’s face it: elves, dwarves, and orcs have been killing each other ever since Tolkein invented them. Combat is a pillar of the genre, and we embrace it. As game designers, we have endeavored to make combat extremely lethal. Toe-to-toe combat generally ends horribly for everyone involved. Battles are often decided before the first die is cast, and whoever seizes the initiative or fights from an advantageous position generally wins.

As with the rest of the game, the rules for combat are pretty damn lightweight. There aren’t even initiative rolls – the moment a player says some violent verb – “I shoot him”, “I charge him”, “I swing at him”, combat starts with that player going first. There’s a subsequent rule, though, which is what I’ll call the Law of No Take-Backsies. You can interrupt the GM and shoot off an arrow, but if it turns out the mysterious figure jumping out from the shadows was actually trying to save you – well, there’s no going back. After the first action, combat works in turns. All of the players get to take their actions, then the GM characters (or vice versa if a GM character attacked first).

On your turn, you get a move and an action. Moving involves changing your character’s distance relative to another character or object – the scale being close (a few yards), short (30 yards), medium (60 yards, roughly ½ of an American football field), long (120 yards), and extreme (a mile). Obviously, this is all theatre-of-the-mind stuff, but your move action can basically move you up or down one of those range increments. If you want, you can trade in your other action for an extra move, letting you cover more distance. (Some actions, of course, like unsheathing a sword or opening a door are “free”).

Attacks use the exact same mechanics as the rest of the game, which is the fastest way for a rules system to win me over (UNIFIED MECHANICS OR DEATH). You roll your five dice, making a skill check with the difficulty equal to your opponent’s relative core rank. The only wrinkle is that your opponent can declare how they’re defending before you roll – so they can decide to parry (using Power) or dodge (using Speed). Missile attacks work similarly, but you can only parry an arrow if you have a shield. You can also try and take cover, using Wits, which seems a little silly – guess they wanted to make sure Wits had something to do in combat. Magical attacks target Resolve, and can’t be dodged or parried or take-covered-against.

Characters have 5HP + their Endurance rank. The moment you hit 0HP, you’re unconscious. Every turn after that, you lose another HP – once you reach -10, you dead. Attacks deal damage equal to the number of successes rolled, plus or minus a few based on the weapon’s damage value. Attacks dealing 1 or 2 HP have no additional effect – they’re minor wounds that will hurt, but not mess you up too bad. A 3HP loss from one attack is a critical wound, which results in you taking another 1 damage any time you move and attack in the same turn. If you take 4 damage in a single attack, you start losing blood, fast – you’re bleeding out at 1HP per turn no matter what you do. Thankfully, the two don’t stack, but two critical wounds will upgrade to a mortal wound. There’s some bubbles to fill in on your sheet to track wound status, but I don’t think it’s a particularly onerous bit of bookkeeping. It does, however, make combat very dangerous. If you take a big hit early on, you’ve gotta get out and get stabilized because it won’t take long until you’re passed out in a pool of your own blood.

You can stabilize a wound to remove its ongoing penalty, but it’s extremely tough to fix your own wounds, so your best shot at ssurviving is to get a friend with some bandages to take care of you. You regain 1HP for every 8 hours spent resting. Nothing else short of magic or healing potions can speed up your recovery beyond that 1HP/8hr speed – which means you are going to want to steer clear of fights as often as possible because they take so damn long to recover from.

There’s grappling, which lets you, well, grapple opponents. While grappled, you can struggle to escape or you can try for a submission hold, which lets you knock your opponent unconscious through MUSCULAR GRABBING. The other lil’ rule tucked away at the end of this section is sneak attacks – basically, if you succeed on an opposed Stealth check, your attack deals +1 damage for each success you got on the stealth roll. If you’re real sneaky, you can deal some really nasty wounds to an unsuspecting foe. There’s also a quick reminder that you can use shards in combat, but that you need two hands to send encrypted messages, so try not to forget the reality of holding a dumb crystal in your hand while narrating combat.

Next time: downtime, crafting, secret hideouts, and the baleful eye of the Risk Eaters!

Hideouts and Downtime

Original SA post

Hideouts and Downtime… Let’s Read Cryptomancer! (Part 9)

Naptime!

Sometimes, heroes need to sleep. In Cryptomancer, downtime is how they do it. Downtime is a block of 8ish hours where the characters know they’ve got a safe place to rest and aren’t in any imminent danger (granted, a rare commodity in an average campaign). Either the players or the GM can declare downtime, and once it kicks in, you’re basically in “getting stuff done offscreen mode”. If you spend downtime resting, you recover 1HP. You can also perform surgery on incapacitated allies, which restores HP at a rate of 1/success rolled (so at maximum, they can recover 6HP – five successes, and 1 from resting). If you meditate instead of resting, you recover MP equal to your Willpower rank. You can also learn a spell, either from a book or a teacher. This requires you to have the free Talent Point(s) needed to learn it.

You can also spend downtime doing crafting-type-stuff: brewing potions, making gear, and setting traps. Basically, you just need the materials, the skills, and the tools, and some good rolls. Larger projects require multiple successes to be rolled – giant projects would need hundreds over the project’s lifetime. Luckily, your less skilled friends (or paid workers) can contribute with their own skills – moving stones, scrounging material, etc. Their successes get added to yours (provided you roll well enough). A masterwork claymore would take 8 successes to make from scratch – impossible to do in one session of downtime on your own, but slightly more possible if you have some friends to help you haul metal and work the forge. I like this system a lot, since crafting is typically a solo activity in RPGs. It’s nice that even those who didn’t decide they wanted to spend points on making shit are still able to help out.

Finally, you can spend your downtime networking or hunting for leads. Rather than manually play out every interaction a player would go through while infiltrating an organization, they instead just make an ascending series of skill checks to simulate their moving up in the ranks. The ranks are Noticed (2), Accepted (5), Respected (9), and Admired (14). The skill rolled can vary with the organization – an alchemist’s guild would require you to demonstrate your alchemy skills, while the king’s court may require charm rolls. Either way, as you accumulate successes, you’ll be getting deeper and deeper into the group’s inner circle. If you’d rather hunt for leads, rather than people, you can do that instead – the book mentions that it’s a great way for the GM to help steer a group in a particular direction if they’re feeling a little aimless. The group can just decide “we’re going to case the neighborhood for leads”, and the GM can come up with an appropriate bit of information to keep them moving forward (provided they roll well on their Query checks, of course). It’s a nice way for players to “brute force” a mystery if they’re feeling stuck, but the idea is that downtime should be a precious commodity – if a prisoner is being executed in three days, deciding to spend 8 hours wandering around looking for clues might be a tough decision for the group to make.

Risk

These are the guys you see when you’ve really, really pissed off the Risk Eaters.

In addition to the individual character sheets, the party also has its own sheet, tracking the group’s progress and advancement through the campaign. The first entry on that sheet is for risk, which is number tracking just how closely the Risk Eaters are watching the heroes. It starts at 1% and goes to 100%, representing how likely it is that the Risk Eaters will intervene in the lives of our heroes. Risk can go up for two reasons: bad operational security, and defying fate. I’ll let the author explain what, exactly, constitutes bad opsec:

Cryptomancer posted:

Bad operational security is when the party is not taking appropriate steps to keep a low profile, protect their communications, and/or mask their affiliations. Some examples include: getting involved in something they shouldn’t, reusing keyphrases over multiple sessions, not cleaning up after themselves (e.g. not disposing of the bodies), resorting to preventable violence, operating in broad daylight, etc. If and when a GM notices these types of activities taking place, she has the option to increase risk between 1 and 3 points, depending on the severity of the behavior, but must notify the players and tell them why it occurred. If the GM is nice, she’ll even advise the players when they are leaning towards bad opsec, so they can course correct before risk is accumulated.

The other way to generate risk is entirely player-led: after rolling, but before the GM narrates what happens, the player can choose to gain 1 risk to convert a botched roll (a 1 on a d10, or a 1-2 on a d6) to a normal success. This isn’t typically worth it unless you’ve got a dramatic failure on the way and something really bad is going to happen (especially if you’ve failed a magic roll). Either way, it’s a hell of a dilemma – do you disadvantage the whole party to save your own skin? I can see this rule inspiring a lot of arguments, but I also think it’s very thematic. Rules that force tough choices onto players are, in my opinion, usually a good idea.

So: you’ve got all this risk building up. How does it actually come back around? Basically, any time the players hit a [i[risk trigger[/i], the GM makes a d100 roll. If she rolls equal to or under the current risk, Risk Eater assassins appear and start wrecking shop. (They can either fade out of the woodwork, or be revealed to be nearby NPCs who’ve been Risk Eater agents all along). Risk triggers occur when players take a session of downtime away from their safehouse, whenever a day passes that the party doesn’t have a patron protecting them, or any time a player rolls a dramatic failure (2 botches, no successes). In the last case, the risk trigger occurs instead of the usual nasty consequences for rolling a dramatic failure.

How the Risk Eaters respond to a failed risk trigger roll varies, depending on how pissed off they are at the party. At first, the party is rated as a Nuisance. 1-2 assassins will be dispatched when needed – which is more than enough to take down most threats! (As always, Do Not Fuck With the Risk Eaters). If they survive and make it to a second risk trigger, the party is now a Disruption. This time, 2-3 assassins show up. If the players somehow make it to a third risk trigger, the party are rated as Destablizers. Whatever the party are doing is putting serious strain on the Risk Eater’s resources and infrastructure (maybe not even knowingly – the fact that the party are still alive could be enough to throw off their plans). This time, they send 3-5 of their biggest, baddest killers. If they survive that, the party reaches the maximum threat level: Existential Threat. I’ll let the author describe what happens next:

Cryptomancer posted:

A threat level of existential threat means that the party’s actions threaten to topple everything the Risk Eaters have spent decades building. In response, this otherwise reclusive and shadowy organization will publicly project their will and declare the players “grand heretics.” Any faction or fiefdom allied with or harboring the grand heretics will be wiped off the face of Sphere, first pummeled by magical weapons of mass destruction fired from the Risk Eaters’ spire, and then finished off by an axis of Risk Eater agents and thrall armies sent to obliterate survivors. No one, not even loved ones, would risk entire civilizations to save a handful of fugitives. The player characters are irreversibly on their own and finished. Grand heretic status is a great time to wrap up the campaign on a nihilistic note. Basically, the campaign spirals to a bloody and unwinnable conclusion and the party has “lost the game.” However, that doesn’t mean the conclusion isn’t awesome. We encourage GM’s to conclude “failed” campaigns with a final scene as epic, nihilistic, and violent as seems appropriate, even if it takes an extra session or two to fully realize it.

So yeah. You cannot win. There’s no way to reduce risk, no way to stop the inevitable – just keep fighting until the Risk Eaters are literally willing to nuke you from orbit, just to get rid of you and your friends. This is definitely something you’d have to go over with the players from the beginning: the game is a death spiral by design, and there’s no getting out of it. Obviously, it’s not hard to houserule around it – you could have risk reduce by successfully completing missions, or just not have the final risk trigger be so apocalyptic – but I like that the game is willing to totally commit to having such a bleak, violent ending.

Strategic Assets

Just like the individual character gets equipment, so too does the party. Except it’s not swords and bows for the party – it’s secret hideouts and deniable spy cells. Strategic assets are earned by completing missions for the party’s patron (at what rate, it doesn’t say – but I would go with at least 1-2 per mission). In the game world, these things cost coin or resources, but you can abstract it away with a cost in strategic resources. Influence, after all, is often just as good as coin. The first kind of upgrade you can buy with your strategic assets are safe house improvements, which make your secret hideout all the cooler. Most of the upgrades are similar to Talents, letting you ignore 1 botch on a specific kind of roll. For instance, the lounge lets you host distinguished guests in a genteel setting, while also letting you ignore 1 botch on any social skill rolls made against the lounge’s guests. Most of the upgrades are semi-portable, but realistically hard to move if you’re in a rush or your safehouse has been burned. There’s an upgrade, Transfer, that lets you smuggle everything from one spot to another – but it costs 2 Assets, which could be better spent on other upgrades. You can stock your base with a library, a dungeon, a forge, a healer’s den (super useful to heal fast!), a ritual chamber, a stable, and more. Everything your party needs to live in comfort while plotting their enemies’ downfall.

You can also spend your Assets on hiring cells of agents to do your dark bidding. They cost 1-3, and when you hire them, you can choose if they’re close, or deniable. Close cells have a degree of trust and loyalty to the party, which also means they can point the finger if captured or turned. They get 4 d10s and 1 d6 on all skill rolls, so they’re highly effective at whatever task you put them to. Deniable cells are the opposite – they only get 2 attribute dice (d10s) on skill rolls, but are managed through cut-outs, dead-drops, and anonymous Shardscape messages. They kinda suck, but can’t implicate you if caught. Whichever you choose, close or deniable, cells can be assigned a mission at any time and will take roughly a day to succeed or fail. (The author recommends 1 task/session can also work if you don’t feel like timekeeping). Oh, and they’ll never operate against the Risk Eaters. The book says that would be the equivalent of trying to “contract a modern private military company to combat the Illuminati”, except, I guess, if the Illuminati were real.

Some of my favourite cells:

Agitators (2 Assets): A group of political operatives who specialize in propaganda, misinformation, and gossip, using their considerable acumen to tarnish reputations, create schisms, and destroy morale.

Cleaner (3 Assets): When one of your other cells fucks up, goes rogue, or turns traitor, this is who you call. The cleaner does things their own way, with particularly grim efficiency. Cells that you “clean” are no longer useable assets, but at least they aren’t a liability any longer.

Echo Collective (1 Asset): A group of “gossips, subject-matter experts, and information peddlers” who collect and share information on a specific topic. Basically, a group of darknet Wikipedia editors who you hire to keep you informed about, say, the latest developments in political news.

Shard Stormers (3 Assets): A collective of badass mage-cryptomancers who will use every cryptomantic spell in the book to assault an enemy’s shardnet, stealing as much information as they can and scattering shard spikes and denial spells around to render the whole thing nearly unusable.

Unlikely Allies (3 Assets): “An ally in the unlikeliest of places: an orcish clan, a gnollish pride, a profane coven, a hated rival house, a dragon, a gang of orphans, an asylum full of lepers, etc.” Basically, your own Baker Street Irregulars.

Cells are fun, not just to have your own little army to order around, but also as a way of letting players pick and choose what interests them. If a particular subplot or intrigue doesn’t catch their fancy, they can send a cell to take care of it on their behalf. Of course, some problems – mostly the Risk-Eater-related ones – will need their personal touch.

There’s also a handful of mounts to acquire – thoroughbred horses, the war-insect gigaphid, and a living tunneler, the molephant. The author also sneaks in the advancement mechanics, such as they are, here: basically everyone gets a Talent Point for surviving a session, with a bonus point if the group came up with a clever hack that took the GM by surprise. Between adventures (every 4-6 sessions), when there’s an appropriate narrative gap, everyone can increase one of their attribute ranks 1 step, so long as they explain what they’ve been up to during the break.

And that’s it for rules. Next time: Golems, firewalls, and more crypto then you can shake a wand at!

DDoS THE GOLEM

Original SA post

DDoS THE GOLEM… Let’s Read Cryptomancer! (Part 10)

pictured: THE ALMIGHTY CRYPTOSQUID

We’ve reached it, folks – 30 solid pages of lovely info on cryptosystems, golems, hacking, and more. Before we dive in, a quick refresher:

- Everyone is capable of cryptomancy – the act of converting a written or spoken sentence into gibberish for those who have never heard the correct keyphrase

- Most keyphrases are simple strings made up of unlikely-to-occur-together words – the phrase can be meaningless, but the words have to be real.

- Advanced cryptomancy involves true names, the secret, utterly unique, names bestowed on children by their parents. All true names also come with a corresponding soul key, which is an even more powerful secret name that cannot be shared with others.

- Your closest allies – those you’ve trusted with your true name – can use that name to encode their messages, which can only be decoded with the corresponding soul key (yours). In this way, people can send messages that are completely guaranteed to only be legible to one person.

- Conversely, you can encode messages with your soul key, meaning they can only be decoded with your true name. This means only the allies you’ve trusted with your true name will be capable of reading the message – and they also know that the message must have originated from you.

- Most covert conversations are conducted over shardnets, interlinked networks of magic crystals that allow their users to leave echoes for each other to hear (either in cipher or plaintext).

- Shardnets are limited in size and scale, but there’s another form of shard communication – the Shardscape. Basically, it’s the magic Internet. Users are able to leave echoes and tag them with themes or phrases to allow other users to zero in on echoes left for themselves or other like-minded users.