Dallas RPG by Bieeardo

Single Post

Original SA post

This is my first shot at something like this, so please forgive me if I don't explain something well, or otherwise miss things. Here goes:

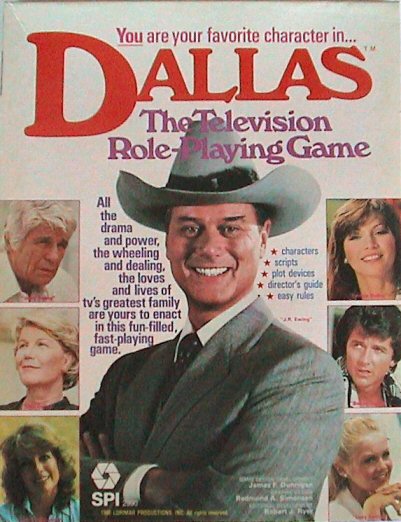

There have been a lot of adaptations of television and literary material to RPGs over the years: Buffy and the Dresden Files, Star Trek and Star Wars before them, and any number that have fallen in between. Some have been innovative, others hopelessly awful. This is the story of the first such adaptation, and unfortunately one of the worst. This is the story of:

For those unfamiliar with the source material, Dallas was a prime time soap opera that ran from 1978 until 1991. It revolved around the relationships between and machinations of members of the Ewing family, inheritors to the spectacularly profitable Ewing Oil Company. Machiavellian bastard J.R. (featured front and center of the image above) was a pop-culture icon for over a decade, and his shooting by an unknown assailant at one season's cliffhanger ending was homaged by the Simpsons and god knows how many other shows and stories since. Dallas was

big

-- but how the Hell did it end up becoming an RPG?

Dallas's developer and publisher, SPI, was a leading publisher of wargames and related supplements during the 1970's, but they felt threatened by the increasing popularity of early tabletop RPGs and decided to stake out a piece of that market for themselves. This began with titles like DragonQuest, which sold modestly, but financial issues prompted them to take more drastic steps: D&D and Traveler seemingly had the hobbyist market sewn up, so they decided to take gaming to the teeming masses. Thus, a deal with Lorimar Productions (owners of Dallas) was inked. Unfortunately for SPI, the game was a spectacular flop. Up past their eyeballs in debt to creditors and having defaulted on a loan from TSR, the latter company vacuumed up and occasionally reprinted bits of their IP-- but never Dallas.

We're going to get some idea of why.

Dallas's presentation falls in line with other games of the day: a shallow box, containing a few thin booklets both meant for the players and for the referee's eyes only. The rules themselves are very thin on the ground-- only five pages of the Rules of Play booklet (with the last eleven devoted to three 'scripts') and a single page summary printed on the back of each sheet in the perforated character sheet booklet. Each of the given sheets is pre-filled, but there are brief guidelines for creating characters of your own in the Scriptwriter's Guide booklet. Oh, and a couple of sheets of minor character and mcguffin cards, but they'll need a bit of context first.

There are three types of character.

Major

characters are PCs: they can Affect each other (which obliges the victim to do something to the aggressors's benefit), Protect others from attempts to Affect them, and Resist such attempts themselves, as well as Control

Minor

characters (traditional NPCs) and

Organizational

characters, which are mechanically identical to Minor characters but represent large groups like government bodies. Minor and Organizational characters cannot control one another, or major characters. But why do you want to control these different characters and outfits, anyway?

Dallas, perhaps harkening back to SPI's roots as a wargame developer, is built around player conflict. In a given script, each major character is given a list of personal victory conditions that involve controlling several different minor characters and organizations, keeping hold of mcguffin items, and fouling other players attempts to do the same. The Director narrates, introducing minor characters and events to keep things churning, and acting as adjudicator for rules issues, while the players negotiate and scheme among one another. The result is more like an old-fashioned murder mystery dinner party game than a traditional RPG. At the end of the script, each player who has fulfilled their victory conditions is a winner. Yup: it's possible for multiple players to win a given scenario. Beyond that, there's a scoring scheme based on how many minor characters you control at the end, and how badly your enemies and allies overextended themselves, which one of the few mechanics covers.

Get money, get power, jerk your asshole relatives around-- that's the 'why' covered, now we get to the 'how'. Every character has the following statistics:

* Sex -- Not really a statistic, but for some reason they saw fit to note this for each character.

* Power -- Allows you to modify the result of conflict tests, can be traded or forcibly taken, and is the main mover in Victory Point calculations. Power is the only statistic that can change during the game, and the rules suggest using poker chips to keep track of them. I'm really not sure if that's because they thought it was a good metaphor, or if they were concerned that players would cheat their Power totals.

* Persuasion -- Allows you to try to Affect another character, thereby forcing them to give you information, or transfer or gain control of a minor character or mcguffin. It doesn't have any requirements or consequences, so it's a good go-to stat... unless you're Ray Krebbs, who is spectacularly awful at it. Using a Power chit gives you a +1 bonus to initiate or defend against Persuasion.

* Seduction -- This might as well be Persuasion all over again, since most characters' Persuasion and Seduction scores are in the same ballpark. Seduction 'suffers' from the caveats that homosexuality isn't addressed in the rules, you can't seduce a relative, and you can't seduce an Organizational character either. No boinking the FBI for you! Again, spending a Power chit gives you a +1 bonus for Seduction attempts and resistance.

* Coercion -- This is where things get more interesting. Like the previous two statistics, successful Coercion can force someone to give you information, or give you control of a minor character, but it can also force another

Major character

to try and Affect someone else. Such is the nature of Power that spending a point gives you

three

point bonus in matters of Coercion. Coercion can also backfire: if you blow an attempt to control a minor character, the

Revenge

mechanic kicks in and everyone else at the table gets a shot at Persuading that character to come under their wing.

* Investigation -- A bit of an odd duck. It can be used to gain information from another character, but is also the only way to peek at details the Director has alluded to (by placing minor character and mcguffin cards face-down on the table), and it lets you help the authorities catch your relatives when they do something illegal.

* Luck -- Luck exists solely as a threat to make scenes take even longer than they need to. When a character has been successfully Affected, they can roll 2d6 against their Luck score, which can range between 2 and 8. If the roll is equal or less than their score, the Affect fails. It has no other purpose in the game but to add extra rolls.

Persuasion, Seduction, Coercion and Investigation each have two different scores, one for Affecting, the other for Resisting.

Sequence of play is fairly simple. Each game consists of a Script, which is broken into Scenes, and each Scene is split into three phases:

The

Director Phase

has the Director set the scene with a bit of narration, put into play Minor Characters appropriate to the Scene, and dictate a time limit for the second phase. The

Negotiation Phase

follows, during which players can trade information, loan Power chits, make threats and plot their way toward fulfilling their Victory Conditions. Finally the

Conflict Phase

is where everyone gets to make good on

some

of those threats. with each Major Character given the opportunity to Affect or Protect up to three characters, including themselves. Unfortunately, it's also where the game's mechanics rear their ugly heads.

Conflict resolution isn't particularly difficult, it's just unnecessarily complicated-- and to a group whose closest brush with math in games has been Monopoly, it might look downright daunting. The aggressor takes his Affecting ability and subtracts the target's appropriate Resistance score. If the result is less than two, it's an automatic failure. If it's twelve or greater, it's an automatic success. For an in-between result, you try to roll under the score. Scores are modified for Power expenditures and Protection, which gives a modest bonus to resist. Oh! And if your roll to

attack

Affect succeeds, your opponent still gets a Luck roll to ruin a third of your machinations for that scene.

If a Character ends up doing something illegal during a Conflict Phase (which is quite possible, given the subject matter), the most elaborate mechanic can come into play: the law! Prosecution and conviction involves a series of Affect rolls, beginning with an Investigation by someone who controls a law enforcement Organizational Character, and followed by three separate Persuasion rolls to gain a warrant, an indictment and finally a conviction. Each step is worth an increasing amount of Victory Points, and a convicted character loses

all

of their Power for the rest of the Episode. It can be tempting for players who are close to their win conditions, but each Affect spent chasing a conviction is one less they can use to advance their primary goals or Protect themselves. Legal proceedings can also stretch out over long periods: if a roll is failed during the prosecution process, it can't be continued until the next Scene.

At the end of the Episode, winners are determined by which Major Characters have completed their Victory Conditions, and among those players Victory Points are calculated based on their Minor Character holdings, the roles they played in bringing another character to justice, and interestingly enough, how many Power points various Major Characters have at the end of the Episode. The last creates a natural web of allies and enemies, as each Major Character gains Victory Points based on the consequences faced by specific others. J.R., king bastard of the family, gets points if his siblings' power bases are eroded. Jock and Ellie, the elderly patriarch and matriarch of the clan, gain a little extra if the other has improved their Power by the end of the game. The others affect each other similarly.

Okay, so the bare mechanics aren't that bad, a little awkward between the math and that Luck roll, but a far sight from D&D and its plethora of classes and statistics. Calculating Victory Points might take a bit of math, but that's just adding, no subtraction necessary. Unfortunately, things take turns for the awkward, unlikely, and unfriendly from there.

First is... well, the subject matter.

Dallas

hit the ground running in 1978, and didn't stop for over a decade. J.R. is still one of the most popular characters in television history. Making some kind of game tie-in (not counting the computer adventure game) was really a no-brainer. Bringing a family-friendly RPG to market was a grand idea too, but combining them? How many families would have seriously wanted to pretend at being a bunch of backstabbing bastards? Monopoly was the closest that most probably wanted to get.

SPI seemed to assume that potential players had large families, too: each of the three pre-written scripts assumed that

all nine

Major Characters were in play, plus a Director. Vague instructions were given to the Director to distribute multiple characters among players (with a warning to not give them natural allies, but not even a whisper about the concept of metagaming), and another rule gave directions for removing Major Characters in order of potency and plot necessity, but the default game assumed ten players and not the four an average family might bring to the table. If it had been pitched as something more like a dinner party game, it may have got the jump on games like

How to Host a Murder

.

While it's clear that SPI took pains to condense the rules as much as possible, they also gave the sample scripts the same treatment. Each is three or four pages, half of which is a paragraph of background and Victory Conditions for each Major Character. The scenes themselves are set in the tersest manner possible, with instructions for setting out specific Minor Characters, and a list of twists and dirty tricks for the Director to spring on the players. The Director is expected to know the rules, explain them to the rest of the players, and then perform without a net. A page-long sample scene gives brief descriptions of deals being cut between players, and longer ones of rolls being made and rules being followed, but there isn't even a paragraph devoted to explaining what role-playing is about, or even how to narrate a scene. The third booklet gives guidelines for creating your own scripts and characters, but the whole exercise feels less like a role-playing game and more like a dynastic Diplomacy.