Fantaji by Astus

Background and Basic Overview

Original SA post

Fantaji Universal RPG Part 1: Background and Basic Overview

Originally called Mazaki no Fantaji , Anthropos Games ran a Kickstarter for their game they described as:

quote:

A cinematic Tabletop RPG inspired by the most gripping JRPGs and rowdy anime, using qualitative stats and a unique, tile-based system.

It only raised about half of the $16,000 they wanted. So they changed the name to just Fantaji , billed it as more of a universal system than they had before, and lowered to the goal to just $3,400. This time the Kickstarter was successful. So, how is the game? Well, let's let Anthropos Games explain it:

quote:

The system is crazy versatile , yes, but how so? Glad you asked! Players "play to" qualitative character Traits and shared Themes to add dice to their pool, banking small successes on early turns to build "Drama" that carries over to future rolls. When you feel like making an attack, you add up your Drama and play to more Traits and Themes to roll against your opponent. The defender does the same, and high numbers win. Every die of mine that beats your highest counts as a success.

"Playing to" Traits and Themes affords open-ended creativity, while deciding how to spend your successes after a winning roll is all strategy. Powers are effect-based, and each roll opens up dozens of options. Oftentimes, shilling out damage is the least of your concerns, and different choices can cause Status Effects, deploy penalties, summon familiars, etc.

To sap your enemies' escalating Drama, build new qualitative conditions on the fly. Flip over a table, light a fire, jump for cover, scale a wall, reload a weapon, give someone a wedgee. Be creative! Whatever you decide is written on an index card and placed on the table, instantly becoming part of the mechanics of the scene. The system constantly dips back and forth between creative, open-ended narrative and sharp, mechanical tactics.

We stumbled upon something that at first surprised us but then got us very excited: Fantaji doesn't reward role-playing. It is role-playing.

Try to ignore that last part, the game has an annoying tendency to act like it is going to blow your mind and that it is, in their words, the “best kept secret in the biggest gaming and anime conventions”. But once you get past the irritating attempts to get you to buy the book (which for some reason continue while you are actually reading the book), the Fantaji system itself is actually kinda cool, and can handle a large variety of situations. Also interesting is how everything is built around four types of "tiles": Character tiles, for the PC's and any recurring nemesis; Obstacles, for everything that gets in the way of the PC's, whether that's mooks, dragons, a locked door, or trying to land on a jet while free-falling; Themes, which cover the overall mood of the story during a specific scene; and Conditions, which are narrative facts that can be used to "trip up" an opponent, or could be used against the players.

In the next part, I'll go through the introduction of the book, and explain a bit more of how this system actually works.

Introduction

Original SA post

Fantaji Universal RPG Part 2: Introduction

quote:

Introductions are funny things, especially when they overlap with first impressions. May this introduction find you animated and interested, and may any first impressions be pleasant for all parties involved. Good to meet you, new friend. Game on.

I am including this header of the first chapter because I forgot it was there, and it made me cringe when I finally noticed it.

The first chapter of the book also introduces the chapter summary section, which very quickly tells you what that chapter covers, and in what order. For the introduction chapter, it goes over what Fantaji is about, some basics of narrative theory and how it relates to the game, the usual “what is roleplaying” section that I'll be skipping, and ends with an explanation of Traits and Drama, which the entire game is built around.

We start off with the three goals for Fantaji: Maximize creative input from the players every turn, reward tactical play and strategic problem solving, and direct unique characters along personal and communal story arcs with engaging climaxes. This is immediately followed by a sales pitch, but this would still be in the free preview on drivethrurpg and they even say directly this is intended to get you to buy the book, so it's not that bad.

Then the book goes into the basics, explaining how Fantaji is different from both traditional d20 and other story games. Every scene in the game is built like a puzzle, and has built-in Themes that guide both player and GM actions in a particular way. The example given is a scene where the party is involved in a losing battle against an army lead by a champion who has been revealed to be the father of one of the PC's. The book explains that in a d20 game, all the dramatic themes, such as resignation, the emotions of the PC fighting his father, and human limitations/mental exhaustion, are all mostly just fluff surrounding the battle. Meanwhile, in other story games, the focus is more on “What happens next in the story”, putting more emphasis on the character instead of the player, and replacing the need for tactics with more concern about the narrative flow. I...don't think that's very accurate to other story games?

Anyways, Fantaji focuses on the question of “What am I going to do next?”, and uses qualitative mechanics to help guide the players on what their character is motivated or likely to do

quote:

The result is neither a Combat Game nor a Story Game, but a Character Game. What we may even be so bold as to call a Role-Playing Game.

Look, I swear, there will be an interesting game after the book stops trying so hard to sell itself.

Finally, we get to section about Traits and Drama, and what the core of this game actually is. Traits reflect the personality and history of individual characters, and Themes are somewhat similar, but cover the overall mood in the story during a particular scene. Both can be played to during an action to give you a better chance of success. Drama tokens are a bonus that carries over round to round, and can represent your momentum or “shit just got serious”-ness.

quote:

Traits are designed to inspire creative role-playing. They are not simply aspects or facets of your hero that are activated when needed, but poetic turns of phrase that instigate your hero to act on every

turn. Each move is an interpretation of your Traits, a creative expression of them.

Traits are actually really interesting to me, because you only start with two of them, but they play into every action you can take, in or out of combat. So the normal guidelines used in other trait-based games don't really work. Traits in Fantaji are meant to be stretched, to have multiple interpretations, and should be poetic and “punchy” instead of being descriptive. I'll go more into what makes a good Trait in Fantaji once we get to the chapter about Traits.

Instead, let's go into the actual core mechanic of the game. Every turn, each player “plays to” one or more Traits/Themes in order to take an action. You can't do anything without playing to a Trait or Theme first. “Playing to” means any action that reflects, alludes to, invokes, or demonstrates something about that Trait/Theme. As an example, the book introduces Garre the spy, who has the Trait “Never Leaves on the Light”. This one trait covers how Garre is inconsiderate and won't wait up for friends, is stingy with resources, and in general doesn't care about the needs of others. You can also take a literal interpretation of the trait and say he's used to working in the dark. Garre's player “plays to” this trait anytime they would pick a lock in the dark, snubs the host of a feast after he tells a joke, or even when kicking a soldier in the head to knock him out (playing on the phrase “knock his lights out”).

All actions in the game are either Checks or Challenges. A Check is a small move or gesture that only plays to one Trait/Theme, and is used to gather momentum (Drama tokens), or to establish a new Condition or detail in the story. For all Checks, you roll a d10 and try to match or beat a 3, 5, or 10, depending on if the task is easy, hard, or somewhere in-between. A character with the Fullmetal Altruist Trait could play to that Trait by stepping in front of his brother to ensure his safety, returning a disarmed opponent's sword, or just drop into a chair a little too hard, shattering it. All would be an example of using that Trait to make a check, the first one establishing a narrative detail (he is in front of his brother), and the other two simply getting him a Drama token.

The other action type is a Challenge, where you make an action directly against an obstacle. You play to as many Traits and Themes as you can, and get a d10 for each one you hit, plus another d10 for each Drama token you have. You opponent then does the same, and whoever has the highest roll among their d10's wins the action, and gets a number of successes equal to how many of their dice rolled higher than their opponent's highest die. Usually these successes are used to deal damage, but can also be used to inflict a Status Effect or to alter Conditions in the narrative. You can't use successes from a Challenge to get more Drama, though. As an example of a Challenge, we go back to Garre the spy:

quote:

“Leaving my allies to fight as they like, I bolt towards the beast, sliding between its legs and slashing at its meaty underbelly.” She “plays to” both Traits by taking into account Garre’s tendencies to ditch teammates (Never Leaves On The Light) and get acrobatic (Slip Sliding Away); she hits the Theme (The Quick and The Dead) by bolting instinctively.

The book then reminds us that while Traits themselves can be a bit flowery, the actions a player takes should be direct and easy to understand. As an example of a bad way to describe an action in order to play to a trait, Garre's player tries to play to her “Slip Sliding Away” trait by saying “Never leaving my place, I slide my torso around and quickly punch the monster in the face.” While the words used to describe the action might bring to mind the trait, the actual action itself is still just punching the monster in the face, which seems to go against Garre's nimble nature.

Well, now we have the basics of how the game is played, so in the next part I'll cover the example of play so we can see how this actually works in practice.

Example of Play

Original SA post

Fantaji Universal RPG Part 3: Example of Play

The setup for the example is the PC's entering a dark cave and being confronted with a Minotaur. There are multiple ways this could go down, but rather than playing the party off as heroes here to save the day, the GM sets up three Theme tiles to set the mood to a slightly darker tone: Horror Unseen , Flight From the Dark , and Flashes of Flesh . Everyone, including the Minotaur, can play to any of these three themes, although how they're interpreted is up to the person playing to it. The GM doesn't just say what each Theme means and force the players to go along with that.

The Minotaur tile is also placed on the table, with four Drama tokens right from the beginning. So any direct attacks against the Minotaur right now would be a terrible idea, and it sets up the monster as a very serious threat that is already charging towards the PC's. But all of the players get one free “reaction round” to make checks to gain a bit of momentum before the fight proper starts. Which means each player gets to make a single Check to either gain Drama or create a Condition.

The first player decides to turn up his lantern, so it gives off more light as the Minotaur gets closer. Rather than being a mostly useless action, or just getting rid of any darkness penalties or whatever, he plays to the Flight From the Dark Theme, and gets a success against an easy target number of 3 on his d10. While he could use the success to make the increased light matter in the scene by creating a condition, instead the player just uses it to gain a Drama token for later rolls.

The second player decides to do something daring, and plays to her Smooth Like Silk Trait by running towards the Minotaur and jumping up and rolling over it's shoulders, ending up behind the beast. She also succeeds at her Check, and uses it to create a “Alandra is behind the charging bull” condition. The book then mentions that just because Alandra jumped on top of the Minotaur doesn't make the roll a Challenge with the Minotaur defending. The action didn't involve harming the Minotaur or directly interfering with it, so it's only a Check. Finally “Brostar the Mighty”, who clearly did not know what kind of game this was going to be before naming his character, tries to leap dramatically over the lantern, but fails the Check. Instead of saying he fell on his face or anything like that, the group decides that the Minotaur just didn't pay any attention to his flashy entrance.

Mostly because the Minotaur is really pissed that someone just rolled over him like he was a sports car, and immediately reacted to Alandra's brief contact with it's skin by turning around and trying to smash her against the wall. And since the “Alandra is behind the charging bull” Condition from earlier would hamper such an attack, the Minotaur loses one Drama token. This is still a bad situation for Alandra, however, as the monster has played to it's Hulking Brute trait, the Flashes of Flesh Theme from referencing the brief contact with Alandra's skin, and the Flight From the Dark theme by turning away from the lantern's light. Combined with the three Drama tokens it has left, the Minotaur gets to roll six dice.

Alandra, meanwhile, decides to jump off it's back while the beast is still turning around. She plays to the same two Themes, both from reacting to the Minotaur starting to turn around while she was still rolling over it, and from going even further away from the light. Combined with a die from her Style Over Substance trait, that's still only three dice. Alandra gets a 1, 2, and 7, while the Minotaur gets a 2, 4, 5, 8, 8, and a 10, getting three successes since three of it's dice rolled higher than the player's 7. While it could use one or more successes to create a Condition, or to eliminate the “Alandra is behind the charging bull” Condition (Conditions do not go away until the end of the scene or until someone uses a success from a Check or Challenge to remove it), it's more likely that Alandra is in for a world of hurt. This is also where the example of play ends, so we don't get to find out what happens to someone who thought rolling over a charging Minotaur was the best idea (it's still a great idea, she managed to remove a Drama token before getting smashed).

Next part is all about Combat Tiles, which also gives a lot of example Obstacle tiles, which is where I first actually got interested in this system. Including a single obstacle tile that sets up a scene where the players have to use hang gliders to land on an airship.

Combat Tiles

Original SA post

Fantaji Universal RPG Part 4: Combat Tiles

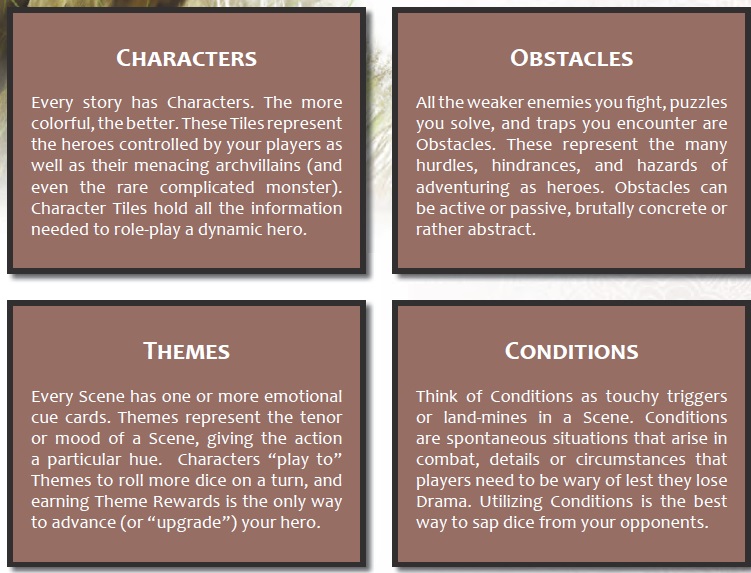

Fantaji uses four “tiles” to represent almost everything in the game, each based on the “four elements of a good story”. In actual face-to-face games, tiles are notecards or something similar, keeping track of everything that's important in the game. The tiles are Characters, Obstacles, Themes, and Conditions, since all good stories are about interesting characters and meaningful conflicts.

Character Tiles are fairly simple, they're your character sheet. Each PC starts with two traits (although they can eventually get more, or make a trait more powerful and let them roll two dice when playing to it), two “powers” which act a little like SFX from Marvel Heroic, three slots for important gear/equipment, and some health blocks. Instead of the usual HP system, Health/Resistance is measured in groups of one, two, or three blocks (the book just uses [3] for a three block and so on), each one requiring that number of successes from a single action to fill it. So a [2] needs two successes to actually damage it, and you can't save successes from separate actions to later fill in a [2] or [3]. Each PC starts with 1 [3] (the mortal wound], two [2]'s (flesh wounds), and four [1]'s (stress wounds). While Character Tiles are mostly for the PC's, any sort of recurring nemesis can also have their own Character Tile.

Obstacle Tiles are used for basically anything that gets in the PC's way. There are two broad types of Obstacles: Typical ones that require you to deal damage to beat them, and Abstract ones that can only be beaten by draining its Drama. Obstacle Tiles also have Traits, Powers, and Health/Resistance. Usually, Obstacle Traits are a bit more focused than Character Traits, simply because if you're throwing an Ogre at your players, it makes sense for it to be focused on being a challenge in normal combat, while a PC has to face all kinds of different challenges. And now the fun part, where we see what you can actually do with Obstacles:

quote:

Avoid the Nightwatch: Keep yourself secret; Keep yourself safe.

Trait: The Walls Have Eyes

Should the tile reach 6DT, you are spotted.

Begins with 4DT.

Fairly simple way to handle stealth, the tile is capable of making checks every round by playing to its The Walls Have Eyes trait, using any success it gets to gain more Drama, making the players have to be proactive about forcing conditions on it to drain its Drama, since there's no way to remove the tile through damage.

quote:

Drop to the Airship: You must drop from the silent glider down to the airship to take it hostage.

Trait: Freefallin'

Should you lose any Challenge, your character slides off the ship and plummets. If you Clash or score [1], you collide with the ship and roll across its surface; you must Challenge again to gain a footing.

[2].

Where the previous tile had a time pressure forcing the PC's to keep managing the rising Drama, this tile is the opposite. The PC's want to gain as much drama as they can before they make their approach. Would probably work better with another Obstacle adding some pressure to get the PC's moving, and also something to happen to the PC's who fail besides “well, guess you aren't part of this scene anymore”.

quote:

Pack of Wolves: The young wolves, hungry for meat and eager to please their leader.

Traits: Gnashing Teeth, Haggard But Hopeful

Powers: Howl (Can swap up to 2DT with any Tile that is part of the pack at will), Pin (When Creating

a “Pack Pinning Their Target” Condition, the Wolves automatically sap 1DT at the same time).

3[2] / 3[1]

Begins with 2DT.

Dire Alpha Wolf: The aged leader of the pack.

Traits: Long in the Tooth, Never Follows, Eater of Bears

Powers: Howl (see above), Alpha Stare (Can “play to” a single Trait of his target on any Challenge or defense).

1[3] / 2[2] / 2[1]

Begins with 4DT.

Escape the Wolves: They will still be on your trail, but at least you can get a mile ahead of them and come up with a plan.

Traits: Long suffering Hunters, On Your Scent, Masters of The Territory

If the Tile reaches zero Drama, you have escaped. Begins with 1 more than twice the Drama present on all remaining Wolf Tiles.

And here's an example of using multiple Obstacles to set up a fun scene about either fighting off the wolf pack, or running for the hills. It's very easy to set up multiple goals for each scene, and you can always add a new Obstacle if the players come up with some other plan.

Themes are basically Traits for the current scene that anyone can play to. They affect the overall mood and tenor of the scene, giving everyone a prompt for how to act in the scene. And instead of the GM just deciding how each Theme should be interpreted, the group as a whole figures out how they want to use a Theme. For example, Hot Sun, Cold Blood gets used in a scene with a giant Terrorsaur rampaging through a village in the middle of a desert. While there are a few ways to look at that theme, the example group turns it into a kind of knowledge check, with them playing to it anytime they play off their characters' growing knowledge of the dangerous and ruthless environment around them.

Themes are also the XP of Fantaji, with each Theme used in a scene being awarded to whichever player demonstrated or enacted that Theme the most. You can spend Theme tiles to get more/stronger Traits, get new powers, or increase your Health. Note that while a player is “awarded” the Theme tile, the Theme can still show up in other scenes. You don't have to create unique Themes throughout the game, and in fact the game recommends reusing Themes you know the group enjoys playing to.

Condition Tiles are the final type of tile (kinda, there's a couple types of tiles we won't see until we get to the Powers section). A Condition is a “matter of fact” that players and the GM introduce during play. Unlike Traits or Themes, Conditions should be written down as straightforward and literal as they can be. So creating a Condition where some goblins are pushed near a roaring inferno would be written as “The Goblins Are Near The Fire”. Kinda reminds me of complications from Marvel Heroic, but there is an important difference between the two: Conditions are also neutral and universal.

A Condition is not inherently negative or harmful, it is simple something that happens to be true. So, “The Goblins Are On Fire” would not be a Condition, as it is completely harmful for the goblins. The previous Condition still puts the goblins in a bad spot, but it's possible for them to use that Condition against someone else, such as by protecting themselves from a sneak attack by using the fire as a barrier. But more than likely, the person who created the Condition is in a better position to use it to their advantage. Something not mentioned in this chapter but that's very important to understand: a Condition can't be removed until either the scene ends or someone uses a success to remove it. So putting someone in a headlock is a bad condition, not just because it is completely negative to the guy in the headlock, but also because you can't just “let go” and end the condition.

Next chapter is How to Play, which goes into more depth of how scenes actually work, and how to create encounters.