A Song of Ice and Fire Roleplay: Why Are IP Tie-In Games Always So Clunky? by Althalin

Worldbuilding and Background

Original SA post The Wheel of Time turns, and Ages come and pass, leaving memor- wait, shit, wrong grandstanding fantasy series.

A Song of Ice and Fire Roleplay: Why Are IP Tie-In Games Always So Clunky?

Part 1: Worldbuilding and Background

I’m gonna dive in to A Song of Ice and Fire Roleplaying, a d6 system based on George R.R. Martin’s series of doorstopper books. This game system is explicitly based on those books, and don’t use the canon of the show.

For those who don’t know, the Song of Ice and Fire books are set in the land of Westeros, which is the Not-Great Britain of Not-Europe.

The setting period of the game is up to the GM (in-system referred to as the Narrator); the default expectation is that your game is set at, or around, the same time as the books take place.

This is 300 years after Westeros’ feuding feudal fiefdoms were conquered by Aegon Targaryen, all-around badass from Not-Rome with two sister-wives and three dragons between them.

Aegon used the dragons to great effect, crushing the natives, and forged a kingdom.

He took the swords of those he conquered, partially melted them, and turned them into the Iron Throne.

What a baller

After centuries of rule under the Targaryen dynasty, Westeros was torn asunder by a rebellion by Robert Baratheon (known to some people as Bobby B). This rebellion was successful, and placed Robert on the Iron Throne; the first non-Targaryen king since Westeros was united.

Though united under a single king, the Seven Kingdoms are somewhat autonomous, and are subject to a lot of infighting and political machinations between the Great Houses that were, formerly, kingdoms unto themselves. We’ll cover the Great Houses in the next post, after which we can hopefully get into the game system itself.

The backstory and worldbuilding are fairly integral to the game system; you’re not likely to be playing this game if you’re not familiar with or interested in the setting. Unfortunately, it’s also somewhat constrictive from the standpoint of the GM.

Ideally, you’re weaving a compelling story of conflict and intrigue, allowing the players to have some level of agency over the nation in which they reside. This isn’t a long-term, D&D Stronghold goal for players who’ve weathered several levels and reached the point where single conflicts aren’t narratively important. The player’s House is its own entity, with its own stats, and nearly 10% of the game book itself dedicated just to the House.

That said, I imagine most campaigns end up in purely alternative history territory - I know ours have. My players wanted a story where they could actually move up in the world, and the canon doesn’t have a lot of room for upward mobility.

But I digress.

The books are centered on political intrigue, so the laws and customs of the Seven Kingdoms are expected to be important in the game, as well. There are a few pages dedicated to the important customs:

A Song of Ice and Fire Roleplaying: Core Rulebook posted:

- All authority descends from the king, who rules by divine right.

- Nobles have more rights than common folk, and higher ranking nobles have more than lower ranking ones.

- Men have more rights than women, except in Dorne where age is more important. For inheritance, male children inherit, from eldest to youngest, and females only if there is no legitimate male heir.

- Lords have a duty to administer and enforce the law in their lands. Common punishments are maiming, execution or loss of property and/or titles. Lords have the right of “pits and gallows,” allowing them to imprison or execute law breakers. Landed knights may also enforce laws, but cannot imprison or execute.

- An alternate punishment is to be forced to “take the black” and join the Night's Watch. The crime is forgiven but you must completely abandon your old life to serve on the wall.

- Execution is normally by beheading. In the tradition of the First Men, the individual who passes sentence must be the one who executes the convicted; this tradition holds mainly in the north, while southern nobles have executioners. A cruel alternative is to stick the condemned in an iron cage called the “crow cage” to die of exposure, named for the crows that gather to pick at the body.

- Nobles accused of a crime may demands trial by combat or trial by lords, where a group of fellow nobles serve as judge and jury.

- A common longstanding tradition is “guests rights,” where a host is obligated to feed guests and cannot cause any harm to anyone who eats at their table for the duration of their stay.

- Children become adults at 16, and a girls first menstruation is an important milestone. Nobles often betroth children much younger than this for political reasons, but sleeping with a girl before her first “moonsblood” is seen as super gross everywhere.

- Followers of the Seven are wed by Septons while followers of the old ways say their vows in front of a weirwood.

- Family allegiances are built by fostering children from the age of 8 or so until their age of majority. Wards are work the same way, except the children are kept as hostages to ensure the good behavior of their family, instead of guests.

- Bastard children are distrusted due to the circumstances of their conception. Every region has a surname given to the illegitimate children of nobles.

Dorne: Sand

The Iron Islands: Pyke

King's Landing and Dragonstone: Waters

The North: Snow

The Reach: Flowers

The Riverlands: Rivers

The Vale of Arryn: Stone

The Westerlands: Hill

The Stormlands: Storm

Technologically, Westeros is roughly on-par with 15th century Europe. This is an age of horse and sword, as gunpowder doesn’t exist in the setting.

Knighthood is an important part of society, with knights being styled as “Ser.” As is typical with chivalrous orders, there are no female knights. Most often, a knight is sworn to a noble House, either trained by the Master-at-Arms of the House or as a result of a marriage. There are wandering Hedge Knights, those who have taken the vows but serve no House, but they are looked upon as untrustworthy scoundrels (not entirely unjustified). Strictly speaking, a Knight was anointed by a Septon of the Faith of The Seven, the largest religion in Westeros. If you don’t follow the Faith, you can’t become a Knight.

The Faith of the Seven, as previously mentioned, is the dominant religion in the setting. The Seven are worshiped in nearly all of the Seven Kingdoms, save the North and the Iron Isles. The religion worships seven aspects of god, embodied in The Father (Judgement and justice), The Mother (Mercy and protection), The Warrior (Patron god of knights and soldiers), The Smith (God of craftsmen), The Maiden (Marriage, young women, forgiveness of women who use sex for manipulation

), The Crone (Widsom, Guidance), and The Stranger (Death).

), The Crone (Widsom, Guidance), and The Stranger (Death). Priests and priestesses of the Seven are known as Septons and Septas, respectively. Oftentimes, a noble House will have a Sept (church) of their own, with a resident Septon to hold services and offer counsel.

So far, so Catholic.

The Old Gods, or the Gods of the First Men, is a religion practiced primarily by those in the North, the wildlings north of The Wall, and crannogmen, who live in the Neck (a natural causeway of swampy land separating the North from the rest of continental Westeros). They are unnamed, innumerable, and omnipresent.

Moreso than in the Faith of the Seven, guest right and the protection of hospitality are taken seriously by those who follow the Old Gods.

Followers of the Old Gods venerate Godswoods (essentially, curated forests) as holy places, rather than Septs. Due to the former ubiquity of the religion, many great castles still have Godswoods despite being held by Houses that worship The Seven.

The most important feature of a Godswood is the Heart Tree, which is generally a large Weirwood. These are large trees with red sap, “bark as white as bone and dark red leaves that look like a thousand bloodstained hands.” Charming. Many of these weirwood trees have faces carved into them, serving as a visual representation of the Old Gods.

Next Time: We cover our bases with the Great Houses, so we can start looking at the actual rules of the game

I Lied

Original SA post

A Song of Ice and Fire Roleplay: Why Are IP Tie-In Games Always So Clunky?

Part 2: I Lied

I was going to run through the Great Houses in this post, but

- They’re generally irrelevant to the actual gameplay

- There are good summaries already out there

- I’m a lazy bastard and

to write up summaries of 9 houses with pages and pages of lore that doesn’t matter in the context of reviewing the game system

to write up summaries of 9 houses with pages and pages of lore that doesn’t matter in the context of reviewing the game system

I’m going to run through the systems for Intrigue, Combat, and Warfare in that order, and then we’ll see about creating characters and Houses.

So with that, said:

Intrigue!

Intrigue is essentially Combat, But With Words. Instead of “Health” you have “Composure,” and instead of dealing “Damage” you’re leveraging “Influence.”

The Narrator is responsible for setting the scene, as expected, which may affect the Intrigue in much the same way terrain affects combat. Perhaps it’s the back booth in a darkly lit tavern, or you’re standing before the Iron Throne accused of high treason.

Both sides have an Objective, which broadly falls into the categories of: Friendship, wherein you try to curry favor; Information, which is self-explanatory; Service, a quid pro quo if you will; or Deceit, where you try to successfully lie your way off of the chopping block.

The book does note that this isn’t a complete list. You can certainly have an Objective that isn’t in one of those four categories.

At the start of every “Exchange” (read: round) you can change your Objective if something interesting happens, or if you realize it’s a moot point.

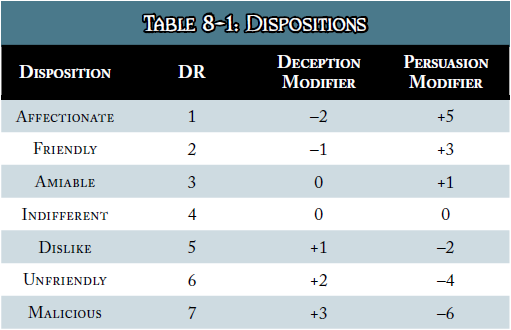

Also determined before you start shooting off words is each side’s Disposition towards the other. Disposition provides the effective “soak” for Influence, reducing incoming Influence by the amount listed.

These Dispositions range from Malicious to Affectionate, with the former reducing incoming Influence by a massive 7 points, and the latter by only 1. Meaning that it’s easier to Influence someone who likes you; go figure.

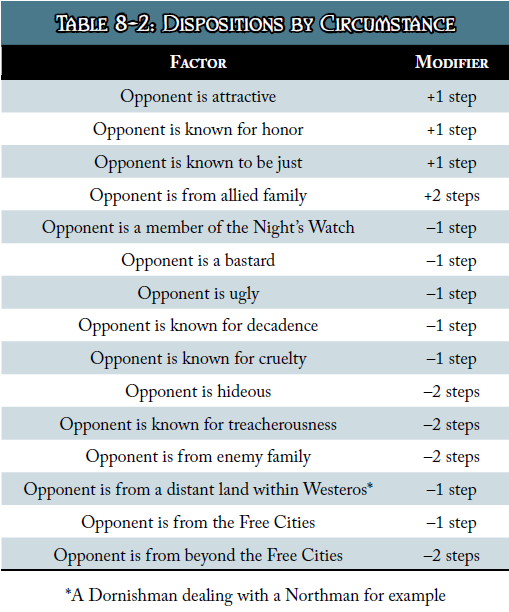

The Disposition of both sides is often modified, and the book helpfully provides a table of likely modifiers. I want to give a shout-out to Green Ronin for making the first example “Opponent is attractive.” That’s pretty in-theme with the books, I guess.

Dispositions can change during the course of an Intrigue, and this can be intentionally done with certain Techniques. We’ll get there when we get there.

Once each side’s Disposition is determined, you finally get to roll for Initiative. This is a Status test, with bonus dice from Status (Reputation) - let’s touch briefly on what that means.

Status is one of your character’s Abilities, determined by their station in life. For player characters, it ranges from 2 (house retainer, hedge knight) to 6 (Lord of the house, lady, heir). For perspective, the King is considered to have Status 10.

Reputation is a “specialty” of Status, representing how well-known you are in the land.

Ability tests are a number of d6s determined by the governing Ability, with bonus dice rolled for relevant Specialties. However, you only get to keep a number of dice equal to the Ability. For example, let’s say we’re making a Status (Reputation) test for a relatively well-known Landed Knight. He has Status 4, and Reputation 2B (+2 bonus dice). His roll, then would be (4 + 2) = 6d6, dropping the lowest 2. For those who like numbers, this means he’ll average an 18. Not too shabby.

Once Initiative is determined, the person taking their turn chooses what action to take. These are similar to Combat actions, with analogues to Aiming a shot (get bonus dice on your next Influence attempt) adopting a Defensive tact, or similar.

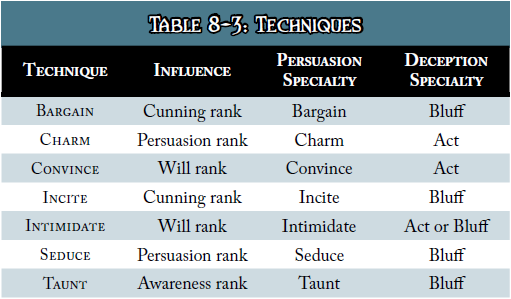

The most common action is to attempt to Influence your opponent, using a chosen Technique.

Technique determines what governing Ability you’ll use, as well as which specialty is appropriate (depending on whether you’re attempting to persuade or deceive your opponent). There are also enumerated consequences for succeeding with the various techniques. These range from getting a discount on goods if you’re bargaining; to getting bonus test dice (thus keeping more of your pool) during your next Intrigue with this opponent.

I want to call special attention to the artwork used to depict the "Seduce" Technique. It's... special. I did y'all a solid and made it as SFW as I could without undermining the glory.

If you successfully Taunt someone whose Disposition towards you is Dislike or worse, they’ll try to attack you (if possible) or flee (if not).

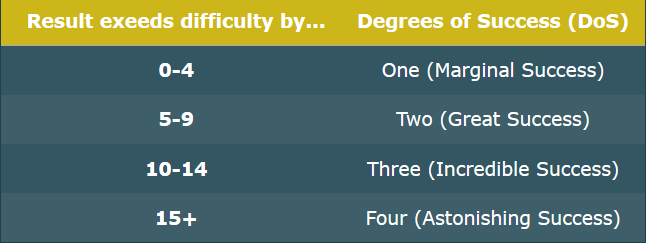

If your Influence test is successful, you deal an amount of Influence “damage” based on your Technique, multiplied by your degrees of success (increment the multiplier by 1 per 5 points over the target you rolled), reduced by the opponent’s Disposition Rating, rinse and repeat.

The book specifically numbers Roleplay as a step in an Intrigue, but almost immediately qualifies it by saying that roleplaying should be happening through the entire encounter. Huh, you don’t say?

In practice, at least in my experience, this subsystem falls pretty flat. It makes social interactions to which it’s applied rather stilted and jarring. While I like that it’s granular and more detailed than “Roll Persuasion against their Wisdom,” it doesn’t necessarily feel more fun.

Instead of roleplaying out an actual discussion, you’re encouraged to take the extra time to figure out what technique you’re using, stack up Disposition bonuses and maluses, finally roll the dice, and chip away at the other person. Unless you have a character specifically built for Intrigue, which will obviously be more or less relevant depending on the campaign, it’ll feel a lot like low-level Fighter play in D&D. You roll a lot, hit a lot less, and what damage you do is underwhelming.

It’s more deterministic than Persuasion/Deception/Whatever rolls in d20, that’s for sure. You’ll notice that’s a theme I’ll touch on a few times as I review this game.

Next time: Combat! (For real this time, I swear, you guys)

Combat

Original SA post

A Song of Ice and Fire Roleplay: Why Are IP Tie-In Games Always So Clunky?

Part 3: Combat

I realize it might seem like I’m going a bit out-of-order in terms of the layout of the gamebook, what with covering Intrigue, Combat, and Warfare (hereinafter generally “conflict resolution”) before character creation

You’d be correct! I’m doing it this way primarily because I want to cover the core mechanics of conflict resolution here, and then go into them in more detail when we get to character creation and how decisions made there actually affect playing the game. We’ll also build an example character, to showcase some of the more Murphy-ish issues with the system.

Anyway, Combat.

If you’ve played a tabletop RPG before, especially in the flavour of D&D or Pathfinder, you probably know about what to expect. You roll for Initiative, wait for your turn, and then get to take some actions.

Like in, for example, FFG’s Warhammer/40k games, you get two half-actions (“Lesser Actions”) or one full-action (“Greater Action”) per turn. You also get Free Actions, with the usual caveat that what does or does not constitute a free action is arbitrated by the GM. Helpfully, the book does specifically mention that drawing a weapon is a free action.

The list of choices is pretty exhaustive.

- Standard Attack - Lesser action, swing a sword or similar

- Divided Attack - Greater action. Attack multiple opponents, dividing your test dice between them as you see fit.

- Two-Weapon Attack - Greater action. Attack with multiple weapons

- Combining Attacks - Greater action. Combine a Divided and Two-Weapon attack.

- Cautious Attack - Lesser action. Use one less die when attacking, but gain +3 to your defense

- Charge Greater - Greater action. Move up to twice your normal movement, and attack with a penalty to hit but a bonus to damage

- Counterattack - Greater action. Essentially a "Ready Attack" action, with the trigger of being attacked yourself

- Disarm - Greater action. Try to disarm your opponent

- Mounted Attack - Varies, but generally you get a bonus from fighting on horseback

- Pull from Mount - Greater action. Try to knock someone off of a horse.

- Pin - Greater action. If you've successfully grabbed someone, you can try to pin them.

- Aim - Lesser action. Gain a bonus die on your next attack.

- Assist - Lesser action. Give a bonus to an adjacent ally's check

- Catch Your Breath - Greater action. Allows for in-combat healing of up to 4 health

- Distract - Lesser action. Reduce an opponent's combat defense

- Dodge - Greater action. Roll away like this is Dark Souls. You make an Agility test for your combat defense, and must take it (even if it's worse than your normal)

- Interact - Lesser action. Reach out and touch something. Interestingly, the book notes that you can combine this with a Move action to draw a weapon, with an attack penalty. Why would you do this when drawing a weapon is a free action?

- Move - Lesser action. Move up to your movement speed. If you take two of these, you can move double your movement speed! Who knew.

- Sprint - Greater action. Move up to your Sprint speed (which varies, depending on your base movement, your Qualities (feats), and what armour you're wearing)

- Stand/Drop - Lesser action. Stand up or drop prone. Notably, if you're wearing a lot of armour, standing up is a Greater action.

- Ride or Drive - Varies. You use your mount to move or attack, but in a different way than a Mounted Attack.

- Pass - Greater action. Gain a substantial +2 bonus dice on your next test.

- Use Ability - Varies. Do something that's not covered by Interact or other normal actions.

- Use Destiny Point - Free action. Spend the system's metacurrency to do something special. (These are Fate Points, for FFG players)

- Yield - Greater action. Give up. Surrender. Place yourself at your opponents' mercy. You can rejoin the combat, but this is !dishonorable! and you take a penalty to Persuasion and Status tests with anyone who witnessed your treachery.

Whew. Generally, most combats will consist of movement, aiming, and attacking. Go figure.

I suppose now is as good a time as ever to go over tests. This is something I neglected to cover in my previous posts, and I apologize. This whole review is a bit haphazard, something I’ll chalk up to the game system and not my own incompetence. (it’s totally because of my own incompetence)

The only dice you need in this system is the classic, the OG, the staple of family board games, the humble d6.

Now available as an anklet

You roll a pool of dice determined by the governing Ability (like Endurance or Fighting), plus any applicable Specialty (a sub-category of the Ability, like Fighting (Long Blades)). These are referred to as Test Dice (+nD) and Bonus Dice (+nB). You keep the highest n dice in a roll, where n is the Ability score. So if you have Fighting 4, Fighting (Long Blades) 2B, you’ll roll (4 + 2) = 6d6, keeping the highest 4.

Various modifiers affect the number of Test and Bonus Dice you have on a roll, such as the Aim action, but you can almost never have more Bonus Dice than Test Dice.

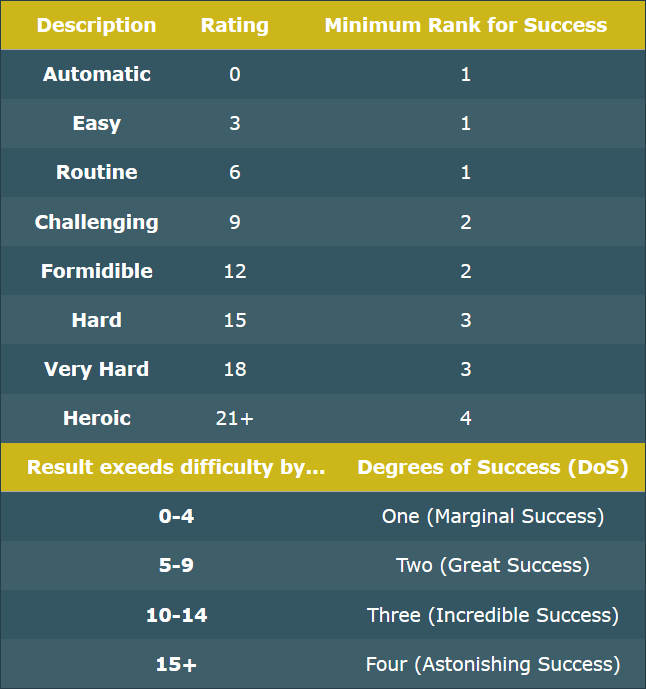

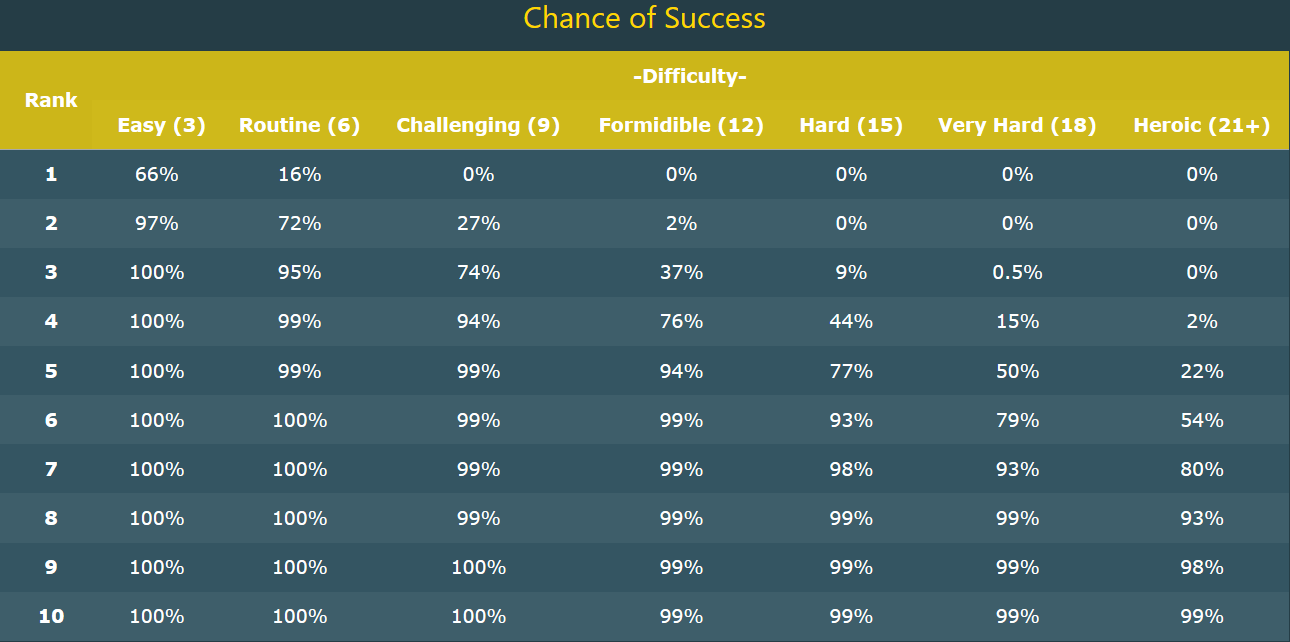

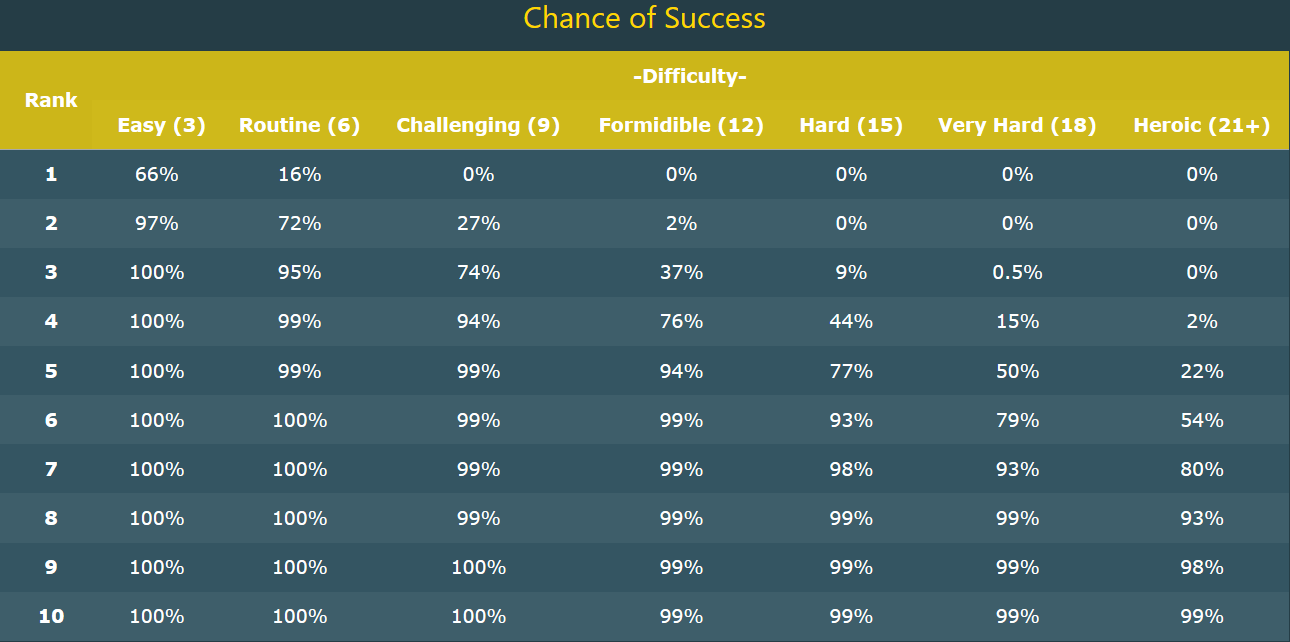

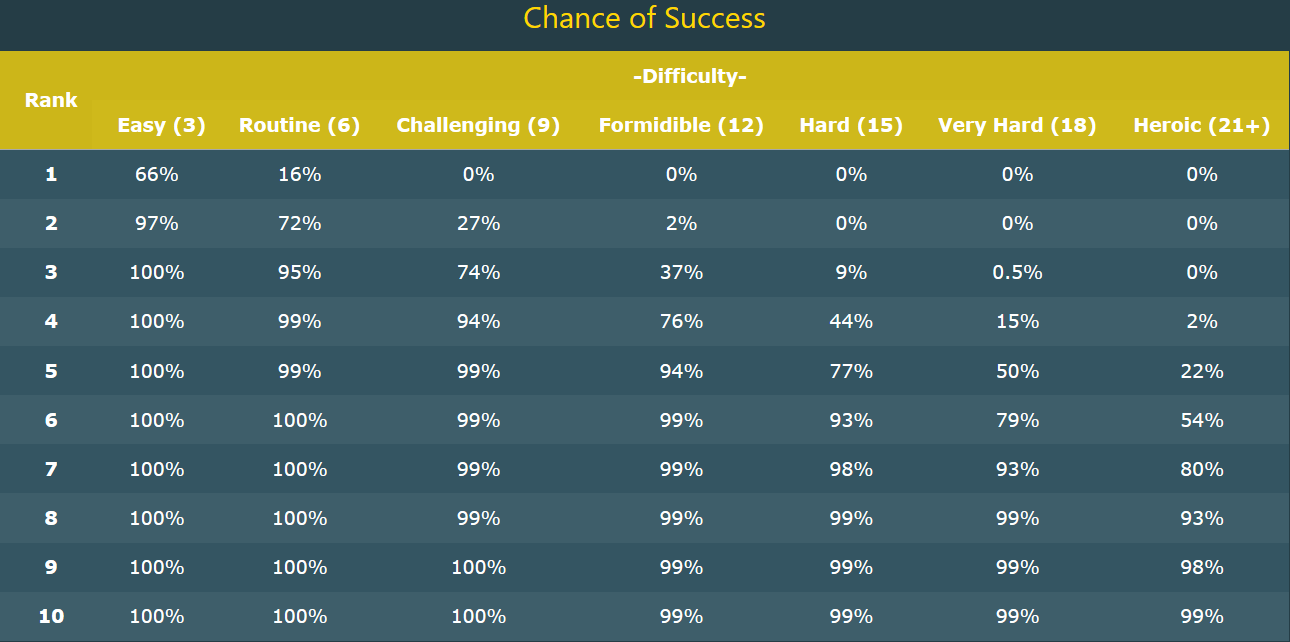

Barring a test against another character’s Abilities or attributes, such as in combat, difficulty of tests is a sliding scale in increments of 3. The game is helpful enough to let you know how many ranks you need, at minimum, to pass a test, as well as the likelihood of passing a given difficulty at a given rank.

Damage

Damage in SIFRP is deterministic, unlike in many systems. Generally, a weapon will do damage based on the governing Ability, maybe with a modifier, in the form of Athletics + 1 (in the case of a Bastard Sword).

Notably, if you score higher Degrees of Success (as defined above), you increment a multiplier on your damage. So if you score two DoS on an attack, you’re dealing double the base damage of the attack. So, using the Bastard Sword example from above, you’d do (Athletics × 2) + 1 damage.

Health

Minor scrapes and cuts are subtracted from your Health, which is your Endurance × 3. You regain all of your Health when a combat ends. More substantial hurt is in the form of Injuries and Wounds.

Injuries

Some attacks or criticals inflict Injuries by default, but you can also choose to take an Injury to reduce incoming damage by your Endurance rank. Each Injury gives you a cumulative -1 on all tests. You can have as many injuries as your Endurance rank. If you can’t take any more, you take Wounds instead.

Wounds

Wounds are major damage. They can be inflicted by critical hits, or you can choose to take a Wound to completely negate all incoming damage from an attack. Each Wound gives you a cumulative -1 die on all tests. This quickly turns into a (literal) death spiral, and even a single Wound can be a death sentence in close matches. You can have Wounds up to your Endurance Rank - 1. If you have as many Wounds as your Endurance rank, you’re dead.

Recovery

So you were reckless or unlucky, and now you’ve got an Injury or a Wound. How do you take care of these? By waiting and making a test, of course! Better hope you’re not planning on actually doing anything in your convalescence, because even light physical activity moves the necessary test to remove a wound up a notch in difficulty.

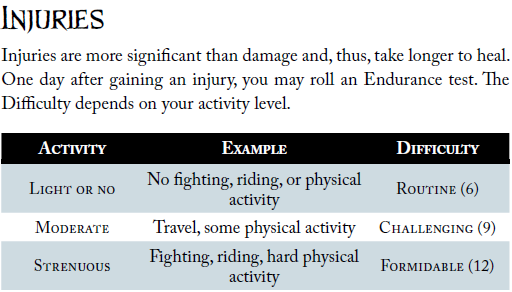

Injuries:

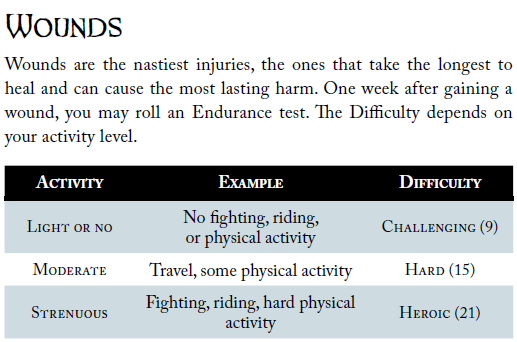

Wounds:

If you’re paying careful attention, you’ll notice that you can’t try to recovery from an Injury until the day after you receive it, and not from Wounds until a week after you receive it. We’ll get to the economy of in-game time in a while, but expect the GM to have to keep a calendar and track time’s passage more strictly than they might in a different system.

So with that out of the way, let’s take a look at the mechanics of recovery. You start with 2 in every Ability, and if you’re combat-focused you’ll likely have Endurance 3 or 4. This governs your Health, so it’s vital to melee combatants. With Endurance 4 (let’s be generous), you’ll have a 99% chance to succeed on recovering from an Injury if you just lie around all day, and a 76% chance if you keep fighting or riding.

Keep in mind that the penalties from Injuries (-1) or from Wounds (-1D) apply to your Endurance test to recover, so if you’ve got 4 ranks of Endurance and 3 Wounds, you need to score in the best case a 9 on a single d6. Not happenin’.

So how do you recover from severe cases of “being nearly dead”? Well, you get someone else to do it for you. Another character (or NPC) can use their Healing ability in place of your Endurance for the purposes of recovery. This is, by leaps and bounds, the best option in all cases. Unless they themselves are Injured or Wounded, you have better odds.

You posted:

Okay, you’ve covered what actions can be taken in combat, how tests work, and how to not-die when you are nearly-dead, but how do you actually mechanically play out a combat?

Right. That was the point of this post.

The last piece of the puzzle we’re missing before running through an example is the Derived Statistic of Combat Defense. This is your AC by any other name.

You determine your Combat Defense by plugging in the respective parts of your Agility + Athletics + Awareness - Armour Penalty + Bonuses. Certain equipment or Qualities can give you a bonus to this, though Armour makes you easier to hit (unlike in, say, D&D and D&D adjacents). In exchange, you get an Armour Rating that reduces all incoming damage by that amount. Full Plate, for example, reduces all incoming damage by 10, but reduces your Combat Defense by -6.

So with nearly 2,000 words of preamble, let’s look at an example combat.

In one corner, we have Ser Gerold.

Ser Gerold is a pretty accomplished fighter, having Fighting 5 (Long Blades 2B), Endurance 4, Agility 4, Athletics 4, and Awareness 3. He’s wearing Hard Leather armour, giving him an Armour Rating of 3 and an Armour Penalty of -2. His Combat Defense is (4 + 4 + 3 - 2) = 9.

His weapon is an Arakh, one of those funky sword-scythe things from a faraway land. It deals his Athletics as damage, +1 because he’s using it two-handed. So a normal hit with one Degree of Success would deal 5 damage.

Because his Endurance is 4, he has 12 Health.

An arakh

In the other corner, we have a Hedge Knight, a wandering man of dubious loyalty and moderate combat ability.

The Hedge Knight has Fighting 4 (Long Blades 1B, Spears 1B), Endurance 4, Agility 3, Athletics 4, and Awareness 3. He’s wearing Mail armour, which confers an Armour Rating of 5 and an Armour Penalty of -3. His Combat Defense is (3 + 4 + 3 - 3) = 7. This means he’s easier to hit than Ser Gerold, but soaks more damage.

His weapon of choice is a basic Longsword, dealing Athletics + 1 as damage. This means a normal hit would be effectively the same as Ser Gerold’s, at 5 damage.

Because he also has Endurance 4, he likewise has 12 Health.

A hedge knight, according to the wiki. His horse looks so sad!

Let’s start by, as always, rolling for initiative. Ser Gerold rolls 4d6 from his agility, with a result of 18. The Hedge Knight rolls 3d6, and gets 14. Looks like Ser Gerold is going first.

Because I don’t want to deal with movement, let’s just assume that they were having an Intrigue and decided to duke it out rather than fight with words.

Ser Gerold is going to take an Aim action, giving him +1B on his next attack. He then makes a Standard Attack against the Hedge Knight, rolling (Fighting 4) + (Long Blades 2B) + (Aim 1B) = 4 + 2 + 1 = 7d6, keeping the highest 4. This results in a 20, which exceeds the Hedge Knight’s Combat Defense (7) by 13. Consulting the table of degrees of success:

We see that this is three degrees of success, considered an “Incredible Success”. Meaning he multiplies his base damage (4) by 3, (12), plus 1 from using his sword with two hands (13).

The Hedge Knight’s armour soaks 5 of this, meaning he takes 8 Health damage, reducing him to 4. Right away, we see that while this isn’t quite the rocket tag you see in high-level Pathfinder, it’s still pretty hurty.

Now for the Hedge Knight. He’s going to respond in kind, aiming and then attacking. His attack roll is 4 + 1 + 1 = 6d6, keeping the highest 4. His result is a 16, exceeding Ser Gerold’s Combat Defense by 7 - a “Great Success,” doubling his base damage. This results in a total of 9 damage, reduced by 3 from Ser Gerold’s armour, resulting in 6 Health damage to Ser Gerold. Ser Gerold doesn’t want to take the damage, and instead receives a Wound in exchange for completely negating it. This means he gets -1D to his future tests.

Ser Gerold, seeing how well his attack worked last time, does the exact same thing. He’s not a man of tactics, you see. 4 + 2 + 1 - 1 = 6d6, keeping the highest 3 (since the Wound he received removes one of his Test Dice, meaning he can keep one fewer). This time his attack roll is a 16. This is still enough to deal double damage on his attack, dishing out 9 total damage - 5 of which is soaked by the Hedge Knight’s armour. Coincidentally, this reduces the Hedge Knight to 0 Health.

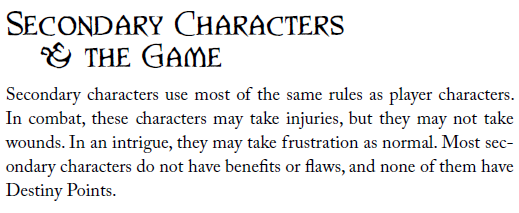

Kind of boring? Yeah, and I’m being a bit of a prick here by using only the most barebones actions and rules possible. That said, this is a pretty true-to-life example of how a combat works out in SIFRP. It’s so lethal that generally the special rules don’t come into play, and unimportant NPCs aren’t afforded the same luxury of choosing to take Wounds as a player character.

With that wordy example done, I’ll wrap up.

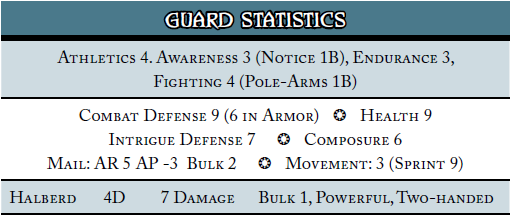

Combat is incredibly deadly. I’ll give points to Green Ronin on this, as it does emulate the books very well. A skilled fighter can often massacre lesser combatants, and a moderately-optimized character fresh to the game can hold their own against the sample NPC given for a city guard.

Next time: Warfare! Or, how they tacked a clunky wargame on top of a clunky RPG and it’s about as you’d expect.

Warfare

Original SA post

A Song of Ice and Fire Roleplay: Why Are IP Tie-In Games Always So Clunky?

Part 4: Warfare

So far, we’ve covered a (brief) history and overview of Westeros, the Intrigue system, and the Combat system. In the third and final part of the series on Conflict Resolution in SIFRP, we’ll talk about Warfare.

Warfare is SIFRP’s mass combat system. Well, nominally. As with the books on which the game is based, much emphasis is put on noble Houses. One of the investments a House can make, and indeed one of the more common and important, is in a standing army. These armies are made up of Units, which are themselves comprised of: 100 men, 20 men and horses, or 5 warships; the composition of a Unit varies (understandably) depending on the type.

I’ll give a quick rundown on the different Unit types available shortly, but first I’ll address a key matter in Warfare: giving Orders.

Each unit has a Discipline modifier, ranging from -6 to +6. Each time a Commander issues an Order to a Unit, they must make a Warfare test against a Unit’s Discipline. Untrained or unruly Units are harder to control, and well-trained Units are easier to boss around. A Commander can issue as many orders as their rank in Warfare. In addition, for every two full Units in an army, a Sub-Commander can be appointed. A Sub-Commander can only issue one order per turn, regardless of their Warfare rank.

There are some basic Orders, as well as more advanced Orders available as a variant rule for the wargaming fans in the group.

Some example Orders, and their Discipline modifiers, are as follows:

- Attack (Basic Order) - +0 - The unit will attack an enemy unit, testing Fighting (if melee) or Marksmanship (if ranged)

- Charge (Basic Order) - +0 - The unit moves up to their Sprint range and makes a Fighting test at -1D, but gains +2 base damage.

- Fighting Withdrawal (Basic Order) - +0 - Make a Fighting or Marksmanship test with -1D, and move up to half of the Unit’s Movement.

- Trample (Advanced Order) - +3 - Cavalry moves their Sprint speed in a straight line, and may make Fighting tests against any unit in their path.

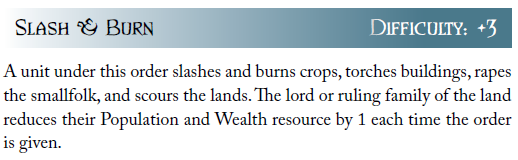

- Slash & Burn (Advanced Order) - +3 - The unit burns crops, scours the land, and “rapes the smallfolk”. Not conjecture, see the image below.

As the (incomplete) sample list above might inform you, Basic Orders don’t confer any additional Discipline modifier. This means that Advanced Orders, despite in some ways being mechanically better (we’re going to come back to our friend Slash & Burn when we cover Houses), also penalize anyone

So, without further ado, let’s take a look at the Units you’ll be ordering to

- Archers - +3; Agility, Awareness, Marksmanship - Lightly armoured and vulnerable in close combat, but provided ranged fire

- Cavalry - -3; Agility, Animal Handling, Fighting - 20 men, mounted on 20 horses. Can be dismounted to form a partial-strength Unit of Infantry

- Criminals - +6; Endurance, Fighting, Stealth - The dregs of a lord’s dungeon, emptied onto the battlefield to soak up casualties and protect more valuable troops.

- Crusaders - +0; Athletics, Endurance, Fighting - Men organized around a political or religious cause. The game notes that they’re “often undisciplined and difficult to control,” but their base Discipline modifier is among the lowest

- Engineers - +3; Endurance, Fighting, Warfare - These are siege engineers, specifically, and have an easier time manning Siege Weapons than the rank-and-file

- Garrison - -3/+3; Awareness, Endurance, Fighting - A Unit assembled to fight on their own turf to defend their Lord’s holdings. Their Discipline modifier is better (-3) than usual when fighting at home, but they become harder to control far afield (+3)

- Guerrillas - +3; Athletics, Marksmanship, Stealth - A specialized force to fight indirectly. Not as useful in a straight-up brawl as other units

- Infantry - +0; Athletics, Endurance, Fighting - The rank-and-file fighters that comprise the spine of an army

- Mercenaries - +3; Athletics, Endurance, Fighting - Soldiers for hire. Notably cheap in terms of a Power investment, but if you want better mercenaries they’ll cost your House some Wealth

- Peasant Levies - +3; Animal Handling, Awareness, Survival - Rabble rounded up from hamlets and town. They’re the single cheapest unit to raise, both in terms of Power and Wealth, but reduce your Population when recruited

- Personal Guards - -6; Athletics, Endurance, Fighting - Among the more expensive Units in the game. They are well-disciplined and easy to command. Unlike other Units, a Commander or Sub-Commander can be Attached (more on that later) to a Unit of Personal Guards and still issue orders.

- Raiders - +3; Agility, Endurance, Fighting; Rough-and-tumble wildlings, clansmen, not-Vikings, or the like. Can hit fast and hard, but not good in a long fight.

- Sailors - +0; Agility, Awareness, Fighting - Guys what make ships go good.

- Scouts - +3; Awareness, Endurance, Stealth - Intended to scout ahead (you don’t say!) and bring intel. Not great in a fight.

- Special - +0; Any Three - The catchall Unit that can be made-to-order.

- Support - +3; Animal Handling, Endurance, Healing - A labor force of camp followers. They’re apparently “trained in caring for equipment, erecting tents, cooking, cleaning” and will get massacred if attacked.

- Warships - +0; Awareness, Fighting, Marksmanship - A small fleet (5) of combat vessels that can be used to fight at sea or transport another Unit into battle. Thankfully the game catches a potential exploit here, and helpfully informs you that you can only build Warships if you have a Coast, Island, Pond, Lake, or River in your Holdings.

Wow, okay. That’s quite a lot of units. In addition to this, each unit has starting equipment, as well as the ability to upgrade their equipment (giving them better damage, or higher Armour Rating at the cost of some Armour Penalty) for a not-insubstantial sum of money.

Because exchanges between units use the same rocket-tag logistics as personal combat, a well-equipped unit is a worthy investment if you’ve got the money lying around.

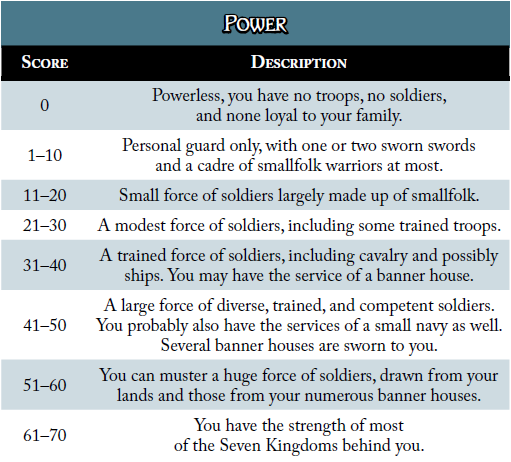

This is all going to tie in nicely when we discuss Houses, and the creation and management thereof. The salient point right now is the Power investment required for units. Power, like Wealth and Population, is one of the resources a House needs manage. When you muster a Unit of men, the Power cost is placed in limbo. It’s not directly removed from your House (not yet, anyway) but you can’t spend it on anything until and unless you disband the unit.

How much Power is a typical House going to have?

Probably in the 20-40 range. We’ll say 30 for good measure.

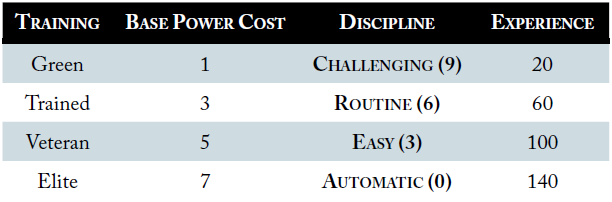

So let’s look through the total costs of recruitment. The first decision made is the training level of the men in a Unit, ranging from Green to Elite. This establishes the base Power cost of the Unit, and affects their Discipline and how much experience they have to improve their abilities.

A Green Unit is obviously the cheapest, but relatively hard to control. Calling back to how Ability tests work, an “Average” person has a 27% chance of passing a Challenging (9) test - keep in mind that Unit types and Orders also affect this Discipline.

As a corollary, an Elite unit (while expensive) comes with the Automatic (0) difficulty, meaning that if the Unit type and Order don’t confer an additional Discipline penalty, you don’t even have to bother making the test. What a world to live in, where the clunky mass-combat system bolted on to a clunky IP-tie-in RPG doesn’t require you to make skill checks to have a unit move.

Because we don’t want to be scraping the bottom of the barrel here, we’ll get a Trained unit. This means the base Power cost is 3, not unreasonable given our total of 30. Getting a Unit of Infantry increases this to 7 (since Infantry has a +4 to Power cost, and a +0 to Discipline). So far, so good. We’ll spend a unit of Wealth to get them better equipment, as well.

And what the hell, we’re feeling saucy. Let’s get two.

Because we don’t want our Infantry to be hung out to dry in a battle, we’ll get some Archers. Again, a Trained unit (base cost of 3) with a +3 from the unit type, bringing us to 6. And a point of Wealth to get them better equipment.

So our total cost for our (meagre) army of 300 men is 20 Power and 3 Wealth. This leaves us a bit of breathing room with 10 Power to spend as we see fit. And, as mentioned before, this Power is invested and not lost. We can disband the unit to recoup the costs if we so choose.

But what if the unit isn’t disbanded? Well, should the Unit be destroyed in battle, it’s gone along with the Power we invested. This makes sense (to me, at least) because of course your House is going to be weaker if you lose a bunch of soldiers.

Which brings me to my next topic: How Warfare actually plays out.

Each army must have a Commander. This is the character primarily responsible for issuing Orders, and tests their Warfare ability to do so. As mentioned previously, a Commander can issue as many Orders as their rank in Warfare.

Orders are issued in a round-robin format; this means that, should you win the Initiative, you issue a single order first. After your first Order is resolved, the enemy Commander issues a single order. This continues until each Commander (and Sub-Commander, if any) has issued all of their Orders for the round. Should one Commander have fewer orders than the other, the tactical genius with more orders gets to issue the remainder in a row after the other Commander has exhausted theirs.

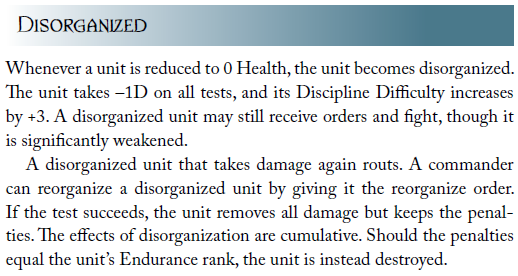

Units have their Endurance Rank × 3 Health, and if their Health reaches 0 they become Disorganized. Remember the death spiral that was Wounds from character-scale combat? Yeah, it rears its ugly head here, too.

A Disorganized unit has a cumulative -1D (they roll one fewer test dice on all Ability checks), their Discipline modifier increases by +3 (meaning they’re harder to command) and if they take any further damage, they’ll Rout. A Commander (or Sub-Commander) can re-organize a Unit by giving them the appropriate Order, which fully restores their Health (somehow) and removes the Discipline penalty. The Unit keeps the -1D penalty, which is cumulative. A Unit that has been Disorganized twice will have a -2D penalty.

If you have a Green unit (base Discipline 9) of Archers (Discipline +3) who are Disorganized (Discipline +3), the total difficulty of a Re-Organize Order will be 15 (mercifully, the Re-Organize order itself does not confer a Discipline penalty). Let’s pull out that chances of success table again:

A character focusing on Warfare will likely have Rank 4 or 5, conferring a 44%-77% chance of success on Re-Organize, respectively.

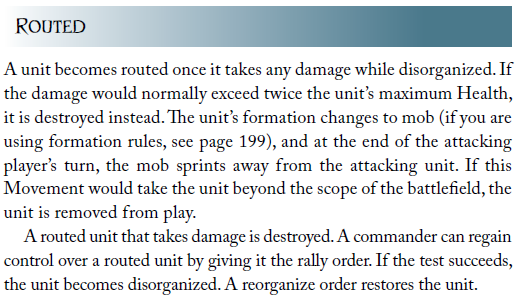

So what happens when a Disorganized unit takes damage? Why, they Rout.

They will attempt to flee the battlefield at the nearest opportunity, cannot be ordered otherwise barring a Rally order. Rally, like Re-Organize, doesn’t confer a Discipline penalty. A Routed unit that is successfully Rallied will become Disorganized, requiring another check to bring them out of that state.

A Routed unit that takes any damage will be Destroyed. That one is probably pretty self-explanatory.

So your army has survived a battle! Now what?

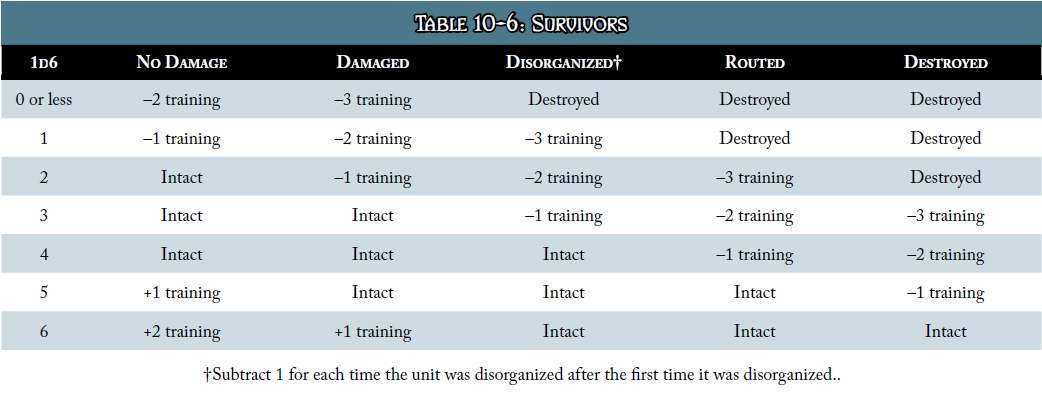

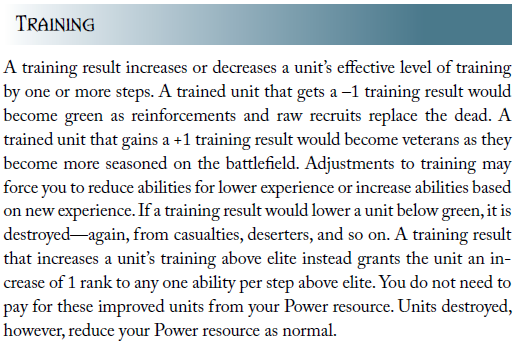

Well, you get to roll 1d6 for each Unit in your army, and compare to the table above. You subtract 1 from the d6 roll for each time the unit was Disorganized (after the first). So even if they were successfully re-organized and are now Undamaged, you could still lose valuable Training levels from the unit. Oh, and to twist the knife: If the Unit’s Training would be reduced below the lowest level (Green), it’s destroyed instead. Meaning there’s yet another good reason to not field poorly-trained armies.

You posted:

What are the rest of the party members supposed to do while one person is playing general?

Ah! Good question. I touched on this a bit in a Murphy for this system (because why not link it here and create an infinite

of picking out flaws in SIFRP).

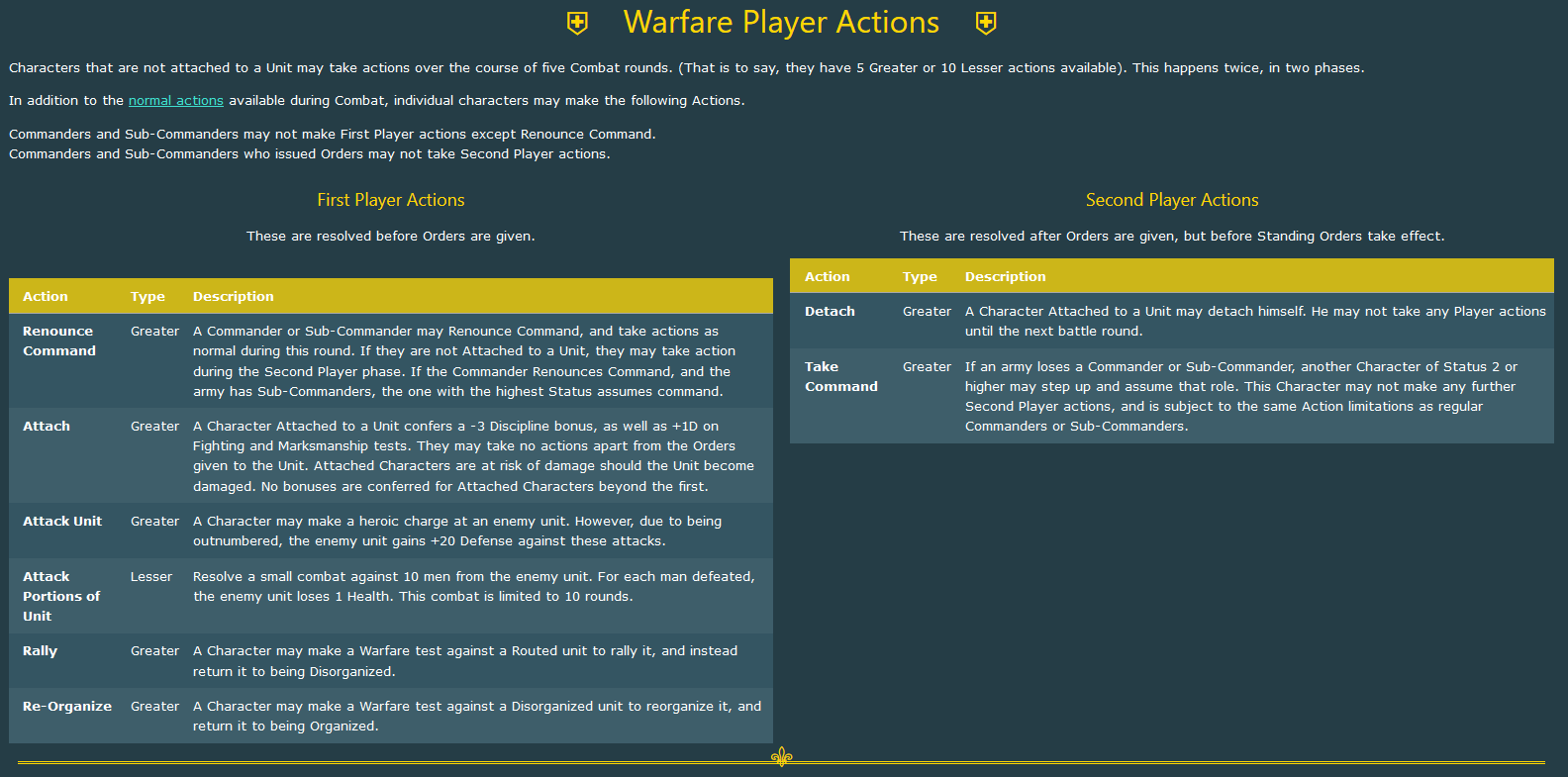

of picking out flaws in SIFRP). Players who don’t have the luxury of being a Commander instead get a list of Player Actions they can take during a round of Warfare.

These are divided into First Player Actions, which take place before orders are issued each round, and Second Player Actions, which take place after orders.

Because the scale of Warfare is larger, the rounds take longer. Rather than the 6 seconds standard across the genre for character-scale, they are a full minute in length. This translates to the characters taking Player Actions having 10 rounds’ worth of actions to take.

The Player Actions range from “ordering Units to re-organize” (super-duper useful, given the penalties for Disorganization or Routing) to “suicidally charge an entire unit of 100 men head-on.”

You could Attach yourself to a Unit, making them easier to command and better at Fightan’, but then you wouldn’t have anything to do for the rest of the battle unless you Detached yourself.

If you have a character optimized for Combat (of the character-scale variety) you could assault a portion of an enemy Unit, 10 men at a time, and likely Disorganize or Rout at least one full unit of 100 men.

Otherwise? I hope you enjoy sitting on your hands as one of your party members plays out a wargame against the GM by themself.

A Song of Ice and Fire Roleplaying: Core Rulebook posted:

The rules of warfare are specifically designed to be a natural extension

of the combat system described in Chapter 9: Combat so that the

Narrator can change the perspective from player characters and their

individual battles to describing the movements and heroics of entire

armies. While the rules here are designed to reflect the ebb and flow

of large-scale battles, many of the peculiarities of combat hide inside

necessary actions to enable the game to proceed in a manner where the

players and their characters remain the focus of the game and prevent it

from devolving into a war game.

You don’t say.

If I had to try and assess the intent behind the Warfare system (which I will, because I’m the one doing the review) I’d say that at first blush it sounds like a good idea.

There’s a level of customization and depth here that rivals that of character-scale adventures, and it ties in supremely well with the House Management system. You have a limited number of resources and you have to allocate them intelligently to build a capable fighting force.

It just happens to fall flat in the execution, which is (I would argue) the most important part of a game.

To wit, my issues are chiefly the following:

- You have a limited amount of experience with which to build your character, and character advancement is slow. This means that, like with Intrigue, you’re unlikely to want to specialize in Warfare at the cost of character-scale Combat.

- It relies on House resources which the player characters have relatively little control over.

- The party is generally not able to meaningfully contribute outside of individual 1v10 combats; substituting the impotence of watching one player control the forces without your agency with a mini-combat that you play out solo with the GM isn’t a great design decision

- It actively punishes the parties that choose to play with Advanced Order and Formation rules.

If you play the game with a variant ruleset, per the core rulebook, each player could control a House rather than a Character. This, to my mind, is the best (and only) way to involve yourself in the Warfare system.

Mass combat has always been a sticking point in tabletop RPGs. I would humbly posit that bolting a wargame on top of an RPG isn’t the way to resolve this.

Next Time: We get into character creation and, if we have the time, character advancement